5 Feb 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala has been banned from entering the UK. The French comedian has long been a controversial figure in his home country, but he became internationally known when West Bromwich Albion striker Nicolas Anelka celebrated a goal with the now infamous quenelle — a sort of inverted nazi salute created by Dieudonné, his friend.

Dieudonné argues he is simply standing up to the establishment, and that the quenelle is an anti-establishment gesture. The facts tell a different story. He has made a number of clearly antisemitic comments, and has been convicted in France of inciting racial hatred.

Dieudonné was set to visit the UK to support Anelka, who has been charged by the Football Association over the incident, and faces a minimum five-match ban. As a colleague pointed out, it’s unclear how, exactly, further links to Dieudonné would help Anelka, but that is now beside the point, as he has been “excluded from the UK at the direction of the Secretary of State”. A letter from the Home Office, obtained by Swiss newspaper Tages-Anzeiger, states that he should not be allowed to board carriers to the UK. If he gets as far as the border, he’ll be turned away at the door, as it were.

But Dieudonné is not alone. Over the years, a number of controversial speakers, covering pretty much the entire spectrum of extremist ideologies, have been banned from entering the UK. The reasons given from the Home Office are almost always along the vague lines of the person in question not being “conducive to the public good”. Below are some the most high-profile cases.

Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer

(Image: Mark Tenally/Demotix)

The American “counter-jihadists” were last May invited to speak at an EDL rally in Woolwich, London, at the scene of the brutal murder of Drummer Lee Rigby. However, they both received letters from the Home Office, informing them that based on past statements they were barred from entering the UK. One of Geller’s comments highlighted was: “Al-Qaeda is a manifestation of devout Islam… It is Islam.” In a joint statement, they declared that “…the British government is behaving like a de facto Islamic state. The nation that gave the world the Magna Carta is dead”.

Geert Wilders

(Image: Frederik Enneman/Demotix)

In 2009, leader of the far-right Dutch Party for Freedom was set to travel to the UK to show his controversial film Fitna — which has been widely labelled as Islamophobic — in the House of Lords. Despite being told by the Home Office before travelling the he was barred from entry because his views “threaten community harmony and therefore public safety”, he still flew to Heathrow, where he was eventually stopped at the border. “Even if you don’t like me and don’t like the things I say then you should let me in for freedom of speech. If you don’t, you are looking like cowards,” was his message to British authorities at the time. The decision was later overturned.

Fred Phelps and Shirley Phelps-Roper

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The father and daughter, both members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church — know, among other things, for picketing funerals — were planning on coming to Leicester to protest against a play about a man killed for being gay. The UK Border Agency said at the time: “Both these individuals have engaged in unacceptable behaviour by inciting hatred against a number of communities.”

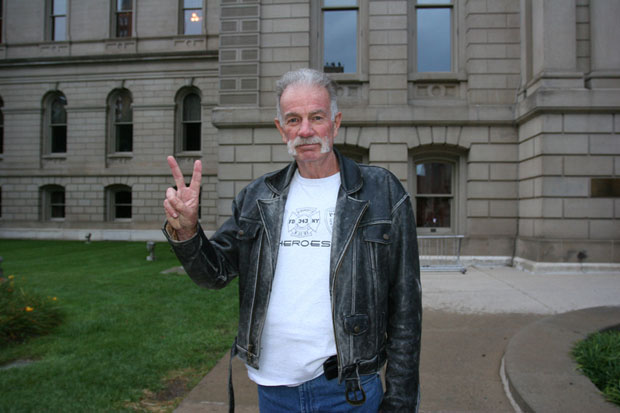

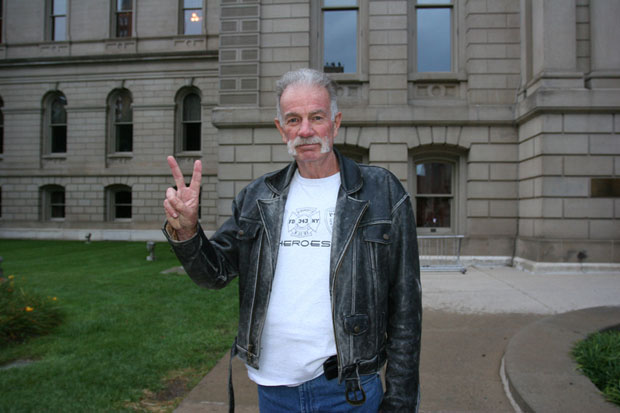

Terry Jones

(Image: Mark Brunner/Demotix)

The American pastor became known across the world when he threatened to stage a mass burning of the Koran in 2010 to mark the anniversary of 9/11 — something which in the end did not take place. In 2011 he was invited to attend a number of demonstrations with far right group England Is Ours. However, he was banned by the Home Office, which cited “numerous comments made by Pastor Jones” and “evidence of his unacceptable behaviour”. Jones responded saying: “We feel this is against our human rights to travel and freedom of speech.”

Dyab Abou Jahjah

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The then Belgium-based founder of the Arab European League spoke at a meeting of the Stop The War Coalition in March 2009. He left the country with the intention of coming back after a few days, only to discover that he was barred from entering Britain. His organisation had previously published “a series of antisemitic and Holocaust revisionist cartoons in response to the Danish Muhammad cartoons controversy.” Around the time of his visit, the president of the Board of Deputies, Henry Grunwald QC, wrote to then-Home Secretary Jacqui Smith “raising concerns about Jahjah”. In a post on his website, he said he believed his ban was “mainly to do with the lobbying of the Zionists”.

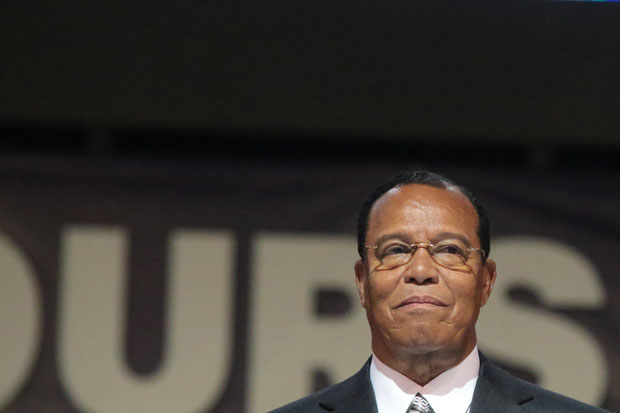

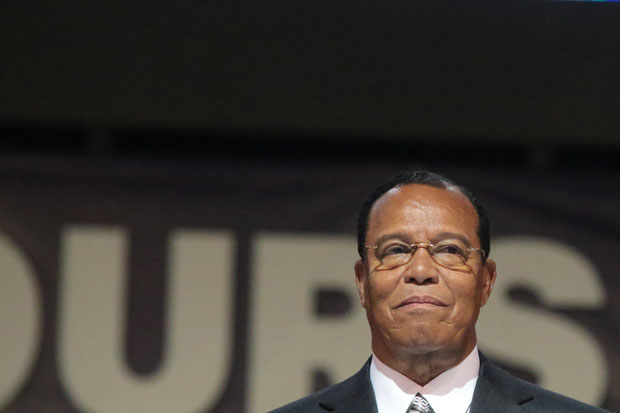

Louis Farrakhan

(Image: Thabo Jaiyesimi/Demotix)

The American Nation of Islam leader has been banned from entering the UK since 1986, due to racist and antisemitic remarks like calling Jews “bloodsuckers” and Judaism a “gutter religion”. The ban was briefly overturned in 2001 by a High Court ruling, but the government won out in the Appeals Court the following year.

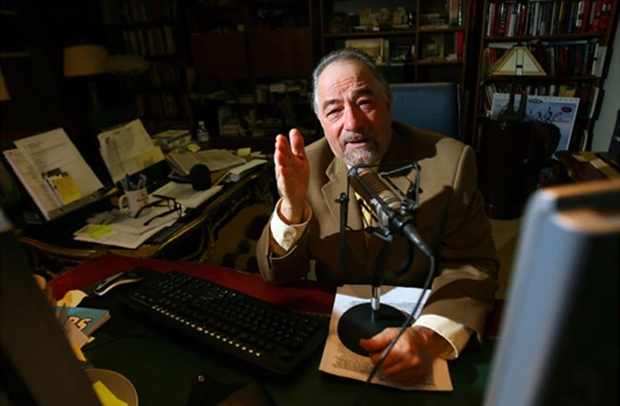

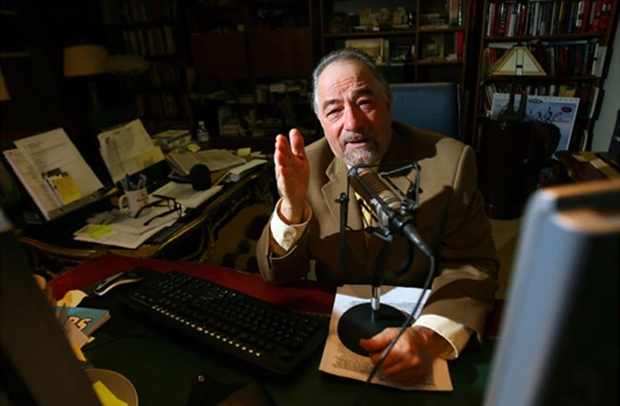

Michael Savage

(Image: Clifford Dombrowski/YouTube)

In 2009, then Home Secretary Jacqui Smith announced a 16-person banned-list, made public in a bid to explain the authorities reasoning for barring people from entering the country. On the list was shock-jock Savage — a popular American talk radio host, who has outraged listeners with comments like “Latinos ‘breed like rabbits'” and “Muslims ‘need deporting'”. He was banned for being “likely to cause inter-community tension or even violence”. Savage reacted with disbelief, claiming he would sue Smith. The ban was reaffirmed in 2011.

This article was originally posted on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Feb 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

The coalition has found a novel way of making life harder for Britain’s journalists. Now it appears to have set itself the challenge of abandoning the reforms without losing face, too.

What’s at stake here is simple: the ability of journalists to protect their sources. This is critical. Without it confidence in journalism is undermined and fewer whistleblowers will come forward in the future.

This is why the government’s latest bid to make life harder for Britain’s hacks – coming so soon after the gagging bill – is so very deeply worrying.

The plans effectively scrap legal guarantees that journalists’ lawyers can contest “production orders” demanding the surrender of key documents.

The measure forms part of the coalition’s deregulation bill – a weighty piece of legislation which aims to scrap a huge pile of red tape it believes has been weighing the UK down for years.

The zeal with which ministers have pursued this bonfire of the rules has risked stripping back important safeguards which make the UK a better country.

For 30 years the regulations governing police applications for the production of journalistic material by the media have been largely unchanged.

Whenever hacks have found their documents being seized by the long arm of the law, their lawyers have had a chance to contest the handover of photographs, files, notebooks and the like.

The result has been the media has had a chance to put across its side of the story when judges hear applications for the production orders.

In legal circles, the name for what happens when opposing lawyers have an argument in front of a lawyer is known as ‘inter partes’ – literally, between the parties.

If the deregulation bill passes unamended, they’d have to find a different name altogether. Because only one of the parties would be present.

This particular bit of red tape would make sure the police have it easy when it comes to winning over wavering judges.

As the responsible Cabinet Office minister Oliver Letwin glibly put it, newspapers would be losing “the guarantee of their day in court”.

The Newspaper Society, which represents titles read by a total of 31 million people a week, puts it another way.

The right to argue against these production orders, it says, are “vital to the Act’s protection of journalistic material against inappropriate police action… they are integral to parliament’s intention to safeguard freedom of expression, facilitate public interest reporting and maintain media independence of the police”.

In short, they really matter. Without them, it’s feared, the courts could decide – very reasonably – that the Commons doesn’t care as much as it did about safeguarding confidential sources from police officers.

There would be nothing to stop future governments undermining or even scrapping the existing safeguards altogether.

One of the most significant changes the committee which decides on these criminal procedure rules could make is to extend the use of ‘closed material procedures’.

These, as the Guardian’s chief lawyer Gill Phillips has written, “contravene a fundamental common law principle of open justice”.

Secret courts are never good news. So it’s no surprise she concludes: “This appears to be yet another backdoor attempt to limit and restrict essential and hard fought journalistic protections.”

Monday’s debate on the legislation was only on its second reading, which means it is at the start of its long journey through the Commons and then the Lords. There is plenty of time, it’s felt, for the government to make a concession and abandon this particular change.

But the recent experience of the gagging bill – a tortuous, hard-fought process which resulted in concessions that quelled the opposition without actually fundamentally changing the feared effect – suggests that seemed improbable.

That was the feeling, at least, before the minister stood up and, in response to a teed-up question from media committee chair John Whittingdale, began what looked a lot like the first stage of a government retreat.

“I have good news,” Letwin announced ingratiatingly at the despatch box. He explained the criminal procedure committee is to be prevented from weakening the rules.

“As it was no part of the intention of clause 47 to do that,” Letwin said, “we are now looking for ways specifically to exempt journalism and all such media items from the clause.”

This is what even cynical campaigners admit is a breakthrough. But it is not yet a white flag. All Letwin has agreed to is a further consultation – an opportunity for newspapers, broadcasters and others in the media to put their views forward.

It’s the same old process, isn’t it? The government blunders into proposing deeply damaging legislation and suddenly finds itself forced on to the backfoot, with its credibility at stake, in an area it should never have gone anywhere near.

In this case, MPs are hoping the coalition has been caught early enough for meaningful changes to take place.

As Tory backbencher David Davis gently suggested, in a desperate effort to be so sensitive to ministerial feelings it sounded almost sarcastic: “This is an area where some of the rules are constitutionally quite important.” That’s one way of putting it, anyway.

Letwin is willing to talk. Will he be willing to move, too? If it’s going to happen, the likelihood is the climbdown will come in the next few days.

The stakes are high. For Letwin, reversing yet another attempt to make life harder for Britain’s journalists is about more than just reputation. It’s about doing the right thing, too.

This article was posted on 4 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jan 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

If you want to know what a party stands for, watch its leader’s speeches. But if you want to know what they’re going to do, read their proposed legislation.

It’s in the details that you learn what a party is all about. Ed Miliband has made several set-piece speeches promising a Labour commitment to civil liberties. But dig into the legislation they support and you find the same old attitudes, making the same old mistakes.

Backbench Labour MP Thomas Docherty has a private members bill going through the Commons today called the Armed Forces (Prevention Of Discrimination) Bill. It’s a shoddy piece of work. He wants assaults – verbal or physical – against members of the armed forces or their families to be treated as aggravated. And he wants them to be included in equality legislation prohibiting discrimination.

None of this should be worth mentioning. Backbench MPs have all sorts of embarrassing and reprehensible ideas, the majority of which never see the light of day. But this time Labour swung its weight behind the private members bill. Shadow defence secretary Vernon Coaker said the party would back Docherty’s efforts and demanded the government do the same.

Coaker was playing a game of chicken with the Ministry of Defence. It would win him a good write-up in the red-tops, a part of the press Labour is struggling to get any traction with. And he guessed that the fear of looking insufficiently supportive of ‘our boys’ would force defence secretary Phillip Hammond’s hand.

Had he considered what the proposals might actually entail for freedom of speech, Coaker might have thought again. But consideration and populism do not make good bedfellows.

The bill would blur the boundaries of discrimination, so that it no longer refers only to who you are, but what you do. This would be a massive legal change. No longer would discrimination law only apply to fundamental human qualities like sexuality or race, it would now be expanded to include commentary on what someone does in their working life.

It would do this in two ways. Firstly, it would expand the common use of aggravated assault from race and religion to membership of the armed forces. Secondly it would include membership of the armed forces under the Equality Act’s protections against discrimination in the provision of goods and services.

The ways in which this type of lazy lawmaking can be abused are not difficult to imagine.

Imagine the squaddies who enter a pub, loud, drunk and aggressive. Unfortunately, this is not rare. Recent Lancet research showed a strong correlation between aggressive behaviour in Britain and psychological trauma experienced in overseas theatres like Afghanistan and Iraq. This puts the barman in an unenviable position. If he allows them in, he risks violence. If he bars them, he is subject to prosecution under equality legislation.

Imagine the anti-war campaigner arguing with the squaddie about whichever conflict Britain is involved in at the time. How strenuous do his arguments have to be before we decide they constitute ‘verbal assault’? If he tells the squaddie that he spilled blood for oil? Or that soldiers are baby killers? The law threatens to criminalise anything but the most tepid and restrained anti-war argument.

Most importantly of all, what precedent does it set? How long will it be before other professions are entitled to protection under equality law? The police would follow the armed forces soon enough. And after them would come the MPs. It is not hard to imagine a situation in which a banker is attacked by a mob and politicians then include them in the blanket of extra legal rights.

Before we know it whole professions would enjoy much stronger legal protections than the rest of the population. The bill is a threat against the principle that all British subjects have equal rights and freedoms.

Mercifully, the government has not taken the bait. An MoD spokesperson told me they didn’t believe legislation was necessary, but that they were instead pursuing their voluntary ‘corporate covenant’ with the armed forces.

But Labour’s decision to swing its weight behind this dangerous bit of populism speaks volumes about the party’s approach to these issues. Despite Miliband’s high talk about civil liberties when he took the leadership of the party, it still appears to have the same crude, dismissive view of freedom of speech as it did under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

It’s the same old deal. They are willing to trade away British legal standards in exchange for a good write-up in the Sun.

This article was posted on 24 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jan 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

The parliamentary struggle over the UK government’s gagging bill, which has overshadowed Westminster in recent months, is all but over. And the end result is bad news for British democracy.

Yesterday ministers secured their final victories against freedom of speech campaigners. Their plans to make it much harder for charities to get their voices heard during election periods – exactly when their contribution is needed most – are about to become law as a result.

The transparency of lobbying, non-party campaigning and trade union administration bill, to give it its full title, has troubled civil liberties activists from start to finish.

Its attempted clampdown on the public affairs industry by forcing third-party lobbyists on to a statutory register, has been roundly dismissed because in-house lobbyists – the vast majority – are simply not included.

This flawed solution to the bill’s main target has been accompanied by a brutal attack on the voluntary sector. The government’s aim was to force small-scale charities, community groups and the like on to a complicated regulatory regime.

Such would have been the chilling effect of this law that most local-issue campaigning during elections would have been stifled when it came to election time. No surprise the legislation was dubbed the ‘gagging bill’.

As it was, bitter opposition to the proposals finally forced ministers to the negotiating table. Instead of lowering the threshold at which charities must begin reporting their activities to the Electoral Commission watchdog, it was increased to £20,000.

This was a major concession. There were other, smaller retreats too, on how long ‘election time’ actually means — it was reduced from one year to 7.5 months — and by excluding some costs like spending on translation into Welsh, or security, from controlled expenditure.

Ultimately, though, these alterations failed to change the bill’s big impact: that important voices encouraging politicians to make promises, and then holding them to their word, are to be stifled.

The Lords did its best to limit the damage. It inflicted embarrassing defeats on the government, which meant when the bill returned to the Commons yesterday MPs had to vote on whether or not to overturn the changes.

As the bill was being debated in the Commons chamber the atmosphere was one of resentment and frustration from the opposition benches — and a smug superiority from ministers. They knew they had already won the war. Now they were about to win the last of its battles, too.

A critical division came over staffing costs. For the bigger household names, like Countryside Alliance or Oxfam, this really matters.

The gagging bill is reducing the total amount a campaigning group can spend in a general election period from £988,000 to £390,000. Say it employs ten staff on a £20,000 salary — by including the staffing costs, the amount actually available to spend on leaflets and demonstrations and advertising is slashed still further.

Yesterday the government whipped its MPs against the Lords amendments. Groups like 38 Degrees had been mobilising their members to urge wavering MPs to rebel. In their offices earlier this week, staff expressed delight as the number of emails sent to backbenchers who’d previously expressed disquiet shot upwards.

Back in parliament, the mood at this campaigning onslaught was grim. One MP I spoke to was so worked up he got his staff to forward me the emails as they came in, to demonstrate just how disruptive they were. The flood which followed was, indeed, deeply irritating – about 50 poured in over the course of just a couple of hours.

Elsewhere, a Tory veteran even phoned up the police to complain about a group of activists wanting to petition him at his home. The bitter irony of this didn’t pass unnoticed.

Ultimately, all the efforts to sway the Commons didn’t make much of a difference. When it came to a vote the coalition’s majority was reduced to 32. But it still won, and the Lords’ improvements were consigned to history.

What caused this diminishing of our democracy? It’s mostly the result of those in power simply not caring much for the views of others. The latest reports from Downing Street indicate that senior No 10 strategists are desperate to find ways of reducing the pledges which candidates make during general elections. It’s much easier to avoid breaking promises, after all, if you haven’t made them in the first place.

And yet that is exactly what democracy, and free speech in Britain, are about: the ability to highlight when politicians are not sticking to their commitments, and the opportunity to encourage them to stick by a cause. Charities are a vital part of this, but the gagging bill is undermining their ability to make the case.

The result is not so much a law which makes it almost impossible for small-scale charities and voluntary groups to campaign during general elections, but one which merely makes the lives of their employees more difficult and awkward.

At the end of it all, democracy in Britain has got just a little bit worse. Our future elections will be slightly poorer affairs than before. The country we were in 2013 is not the country we shall be when, in a short while, the Queen finally hands royal approval to her government’s gagging bill.

This article was published on 23 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org