In a controversial ruling, a French court has ordered Mediapart to withdraw Bettencourt “butler tapes” from its website.

Since Tuesday 3 November 2015, the fourth part of the Bettencourt case is being judged in a Bordeaux court. This time the accused is Pascal Bonnefoy, former butler of Liliane Bettencourt. Bonnefoy is accused of privacy violations in conjunction with media outlets Le Point and Mediapart, which reproduced excerpts of recordings Bonnefoy had made. The tapes allowed the French justice system to condemn several people for abuse of a vulnerable person — the L’Oréal heiress — and spawned investigations into alleged corruption.

Following a court decision that became effective on Monday 22 July 2013, independent French news website Mediapart has had to withdraw the infamous Bettencourt “butler tapes” from its website, as well as 72 articles including quotes from the recordings, prompting a campaign of solidarity in the French and international media.

In the balance between freedom to inform and right to privacy, the court ruled that it was more important to protect the right to privacy. Reporters Without Borders published the censored content on Wefightcensorship.org, a website that has until now published content from countries more commonly associated with abuses of press freedom, such as Turkmenistan, China and Belarus.

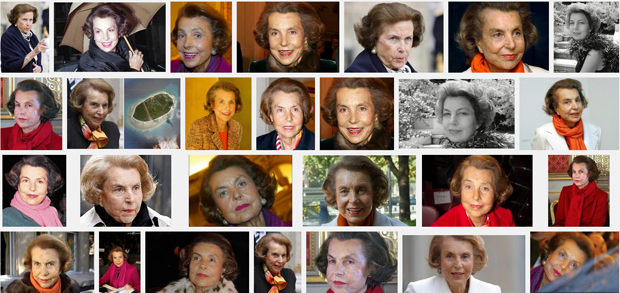

Between 2009 and 2010, Pascal Bonnefoy, the butler of L’Oréal heiress, 87 year-old Liliane Bettencourt, secretly recorded conversations between his boss and Patrice de Maistre, her wealth manager, as well as other advisers. As Bonnefoy explained in a recent interview with French Vanity Fair, he did this because he thought Bettencourt was being manipulated by a close circle of advisers and friends. Apalled by the conversations he had intercepted, he gave the recordings to Bettencourt’s daughter who gave them to representatives of the justice system.

A 21 hour-long copy of the tape also came in possession of Mediapart and Le Point magazine. Journalists at the two publications edited down the content to one hour, getting rid of references to Liliane Bettencourt’s private life. What they kept was damning: the excerpts published in June 2010, contained, among other things, evidence of tax evasion and influence peddling, they raised suspicions of illegal political funding and interference in justice proceedings by a French presidential adviser.

The butler tapes have been at the centre of a lengthy investigation, as the Bettencourt case gradually unfolded, turning into the Bettencourt-Woerth case (when it appeared that Eric Woerth, successively budget and labour minister during Sarkozy’s presidential term, was involved) and the Sarkozy case, when France’s ex-president was placed under investigation over allegations that he had accepted illegal donations. The recordings were recognised as evidence by the criminal chamber of the appeal court in January 2012 and will be at the centre of a trial in Bordeaux, which date is still to be announced.

Meanwhile, following a complaint by Bettencourt’s legal guardian and by her former wealth manager, the Versailles appeal court ruled on 4 July that Mediapart and Le Point had to take down the recordings and all direct quotes from it or face significant financial penalties (10,000 euros per day per infraction). They will also have to pay 20,000 euros of damages to Bettencourt if her representatives claim the fee.

“What’s the balance between the freedom to inform and the right to privacy? This is the question raised by this ruling”, says Antoine Héry, head of the World Press Freedom Index at Reporters Without Borders. For him, the excerpts of the recordings used by Mediapart and Le Point are of public interest. “Erasing this content means erasing a part of this country’s collective memory”, he says. “Mediapart has written a lot about the case, which marks an important moment of French Fifth Republic’s history, and possibly one of the greatest scandal it has known,” he adds. The ruling might have a chilling effect – and make it more difficult for journalists to break stories in the future, for fear of costly court proceedings and fees. It will also make it complicated for Mediapart to write about the upcoming Bordeaux court case, as its journalists won’t be able to quote from the recordings, which constitute a very central piece of evidence.

“This decision”, says Edwy Plenel, a former Le Monde editor, who co-founded Mediapart in 2008 with other former print journalists, “is incredibly backwards, and recalls the very reactionary decisions taken by the judiciary system during the Second Empire, which showed an increasing tension towards the growing modernity of the publishing world and journalism.” For Plenel, the verdict can only be read as a reaction to changes prompted by the Internet – which allows a free circulation of information. It is part of a greater debate which has been taking place around the Snowden and Wikileaks case, and the Condamin-Gerbier case in Switzerland, where national security, banking secrecy and protection of privacy are opposed to the right to inform. Mediapart will appeal to the decision in France and take the case to the European Court of Human Rights if needs be.

The solidarity campaign which immediately followed the Versailles court decision has shown that such a verdict was absurd in the era of internet. After three years, the Bettencourt file has entered the public domain and has been copied everywhere: it’s easy to find on BitTorrent or Reflets.info. Following the verdict, several publications immediately offered to host the content that Mediapart was obliged to censor as a sign of protest. Among them, Belgian national newspaper Le Soir, French publications such as rue89 website, Les Inrockuptibles magazine or Arrêt sur Images website. Media organisations, NGOs and unions launched an appeal entitled “We have the right to know” supported by 53,000 signatures, which said: “When it comes to public affairs, openness should be the rule and secrecy the exception.”

Following the Streisand effect, the Versailles verdict seems to have backfired. Never have so many people listened to the Bettencourt tapes, nor read about the story, nor be interested in Mediapart, an investigative journalism website which has proven its ability to set the news agenda in France, and created a new business model as French printed press sunk deeper into crisis – Mediapart charges readers for access and doesn’t carry any advertisement.

Le Monde, France’s most well-known newspaper, abstained from the solidarity campaign, as well as conservative newspaper Le Figaro, a decision seen by many as disappointing, given that Le Monde was associated with Wikileaks and Offshore Leaks earlier this year.

“For me”, says Plenel, “this can be explained by a certain illiberal tradition within the French press, the fact that in this country journalism is often too close to political power, and also by a certain fear of the changes that Internet is causing in the media – embodied by Mediapart.” This distrust of new media associated with the Internet could explain the smear campaign endured by Mediapart by a good part of the traditional and conservative press from December last year, when the website broke the Cahuzac scandal (also prompted by a tape) which caused France’s budget minister to resign in April, finally admitting that he had a secret offshore account. France’s traditional written press seems to have become extremely cautious, and unable to break scandals, a task which was filled for a long time by the satirical weekly publication Le Canard Enchaîné, and now is also filled by Mediapart.

How does France rank on the Press Freedom Index?

“It’s only 37”, says Héry. A mediocre rank explained by the mediocrity of the law framing the protection of sources for journalists, and by reforms passed during Sarkozy’ presidency which streightened governmental control over France Télévisions, the French public national television broadcaster – allowing France’s president to name its CEO. Hollande’s government is expected to work on these issues – and new laws on the protection of sources for journalists, the status of whistleblower, and the nomination of the head of France Television should be passed. On Friday, the appeal launched in solidarity with Mediapart was handed to Aurélie Fillippetti, minister of culture and communication of the Hollande government, as well as the whole Bettencourt file.

Interestingly, the Versailles verdict took place on the same day France refused to grant asylum to Edward Snowden – a strong reminder that France could do a lot better to protect the right to inform and to be informed.