Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

If chickens are at last coming home to roost in the phone hacking scandal, the people we need to thank most are a bunch of celebs. Sienna Miller, Steve Coogan, Chris Tarrant, Paul Gascoigne and Andy Gray are now heroes of free speech in Britain, as are Lord Prescott, Nicola Phillips (formerly Max Clifford’s assistant), Sky Andrew (football agent), and all the rest of those taking legal action over hacking.

They may be unlikely heroes in some ways and they may be in with a chance of damages, but without them this affair would probably have died months ago. And make no mistake about it, they are brave, because Rupert Murdoch’s News International is a very powerful enemy to make.

Peter Oborne’s Channel 4 documentary Tabloids, Tories and Telephone Hacking reported that the News of the World compiles dossiers on people in public life even when it isn’t planning to publish. Why? Just remember the line attributed to Greg Miskiw, a former news editor at the paper: “This is what we do: we go out and destroy other people’s lives.”

Oborne also found an MP prepared to talk, cautiously, about intimidation — Adam Price. And another MP, Tom Watson, put it as bluntly as could be in the Commons chamber: “We are scared of the power she wields…” He was referring to Rebekah Brooks, chief executive of News International and Christmas drinking chum of David Cameron.

Imagine you were an actor, a television personality or a young PR worker, and think about how much influence Brooks could have on your life. She is already the boss of four national newspapers which all have the power to promote or damage careers. And with her links to Sky, ITV, Five, Shine, Fox TV and in Hollywood 20th Century Fox, her influence goes much, much further. You would need a lot of nerve to take that on and stay the course.

For Brooks and her colleagues the stakes in this scandal are very high. Andy Coulson was one of them, their man in Downing Street, and he is out. Current News International chiefs know they are on record saying lots of things that now look very hard to defend. And the people suing the company threaten to make things much worse by dragging into the open the whole story of wrongdoing at the News of the World.

It so happens that most of those taking legal action are celebrities, but they could have been anyone at the wrong end of the tabloid machine. And for almost every celebrity there are others — secretaries, mothers, boyfriends, whatever — who believe they were collateral damage because they left voicemails that were listened to.

They need courage to keep going and they need support. News International is fighting all the way and the remarks of Miskiw and Watson give us a hint of how nasty that might be.

Brian Cathcart teaches journalism at Kingston University and tweets at @BrianCathcart

Two more independent journalists were detained for alleged participation in the protests following the disputed election. Boris Goretsky of Poland based Radio Racyja and Yevgeny Vaskovich of Bobruisky Kunyer were detained by KGB authorities on Monday. Goretsky was sentenced to 14 days in prison on 18 January for participation in anti-government protests on 19 December.

International recognition offers a degree of protection to investigative reporters. But, writes, Lydia Cacho being in the limelight presents a new set of dilemmas

International recognition offers a degree of protection to investigative reporters. But, writes, Lydia Cacho being in the limelight presents a new set of dilemmas

Translated by Amanda Hopkinson

The first call is the one you never forget. The person uttering the death threat has spent days preparing for this moment — to let you know that your fate is sealed. Up until this phone call, threats were something ethereal and alien, something that happened to other people.

Over time, I learned a lesson that many journalists and writers have learned before me: that becoming the news is a double-edged sword. It can weaken and wound. It unsettles us and sets us apart from our colleagues and loved ones. The threats become as important as the original story.

This dilemma dominates the rest of our lives, because for us to come through safely we need to be out there, in public, and never be silenced. At the same time, we have to remain on guard, watching our backs, alert whenever we see a police or military patrol, reacting instantly to any sound resembling a shot, tensing every time a motorcycle accelerates or approaches, permanently on the look out for a weapon in case the rider is a hit man. And on and on, we have to proclaim to the four winds, until we’re fed up with doing so — and everyone else is fed up with us too — the name of the Mafioso, the politician, the policeman or the corrupt businessman who has put a price on our heads. Yet we yearn for the privacy and anonymity that would allow us to move around without being recognised, for those times when we used to have no need to conceal the names of our family members (for they are now vulnerable too).

We are the enemy, and truth is the enemy of a nation refusing to engage in self-criticism and assume responsibility for its own tragedy. Sixty-four journalists have died in my country. Not one of these murders has been explained.

In Mexico, death threats are hardly newsworthy. Nor is death, or the struggle to remain alive. Maybe this is why my father, in solidarity and with great emotion, asks me why I refuse to accept the idea of living in another country for a while, one where I would not be considered an enemy of the state because I defend human dignity.

Six years ago, when I was imprisoned and tortured by a mafia who trafficked in minors and in child pornography, parts of the Mexican media exclaimed: “A woman who opposes mafia power”, as if in surprise. Thanks to their reaction, society looked at and listened to me, but most importantly of all, it reacted and demanded justice for the hundreds of children who are the victims of sexual tourism and child pornography. Legislators created new laws to protect children, and when I was cleared of defamation charges, women on the streets, old and young, applauded and embraced me. They stopped me in public places to congratulate me on having reminded them that truth has power – and so do women who refuse to subject themselves to macho violence.

Only the other day, as I was pushing my trolley along the supermarket aisle, two older women approached me and asked, “Are you the writer?” Timidly, I said, “Yes”. One woman threw herself at me for a typically Mexican-style embrace, informing me that her granddaughter wrote an essay at primary school on her chosen heroine. It was me. “Why did she choose me?” I asked, and she answered: “Because we are all a little bit like you, and you remind us of it, when you refuse to give in, when you won’t hold your tongue, and when you smile and tell us that the world is also ours.”

Perhaps that’s what it comes down to in the end. Journalism brings it all together. We can’t ask others for something we are not inclined to give. There are moments to listen and others to be listened to. It is not enough to arouse empathy; it is not our job to make people cry. What we have to do is to reflect an outrageous reality with such power that it inspires the hope that all people want to participate in and be responsible for change. Objective journalism does not exist: we are not objects. We are subjects, so we write subjective journalism, and to do that well, everyone’s rights and everyone’s lives are of equal importance. Sometimes we tell the story. And at other times, we are the story.

Lydia Cacho’s most recent book is Slaves of Power: A Journey into Sex Trafficking around the World (Debate). She was awarded the PEN/Pinter Prize for an international writer of courage in October 2010

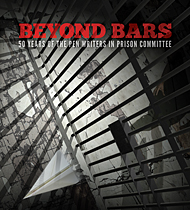

This is an edited version of an article which appears in Index on Censorship’s latest issue, Beyond Bars: 50 Years of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee.

This is an edited version of an article which appears in Index on Censorship’s latest issue, Beyond Bars: 50 Years of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee.

If you want to read more from Lydia Cacho, subscribe to Index on Censorship via Exact Editions. You will gain access to Index’s archive including Volume 38, Number 3 featuring Terror on the Highway in which Cacho tells the remarkable story of how she survived an abduction

Google lifted some of its restrictions for on-line users in Iran on 21 January. Google unblocked access to Google Chrome, Google Earth and Picasa, previously US trade sanctions had prevented Iranian users from accessing the site. The restrictions are still in place for users linked to the Iranian government.