After ultra-orthodox Jews used concentration camp symbolism in a protest against secular authorities, a new bill seeks to control use of Nazi-era imagery. Daniella Peled reports

After ultra-orthodox Jews used concentration camp symbolism in a protest against secular authorities, a new bill seeks to control use of Nazi-era imagery. Daniella Peled reports

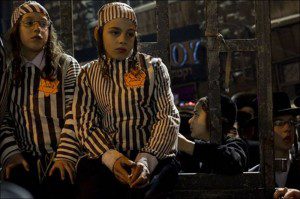

A recent demonstration by ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel in which children were dressed up as concentration camp prisoners has sparked a new potential addition to Israel’s laws on freedom of speech.

The bill, which has already passed its preliminary hearing, would mean anyone using Holocaust imagery or Nazi labels in public may soon face a NIS 100,000 fine and up to six months in prison.

But this bill is far more about controlling the parameters of debate than about showing respect to the victims of the Nazis.

It’s instructive to look at who is sponsoring the bill. Uri Ariel of the National Union party is a settler leader who only this week admitted giving right-wing activists information on Israel Defence Force movements.

“Unfortunately we have been witness in recent years to the cynical exploitation of Nazi symbols and phraseology,” he said this week, “which is offensive to Holocaust survivors, their families, and many others among the Jewish people.”

Indeed we have, and not least from members of his own constituency.

One of my enduring memories of covering the disengagement was of seeing two little girls in the West Bank settlement of Homesh, due to be evacuated later that day, skipping along wearing matching stars-of-David cut from orange cloth, the colour of the anti-disengagement movement. They were also wearing matching home-made hula skirts made of ribbons of the same material.

That was a theme that ran through the disengagement to the point it lost its ability to shock — the orange stars, the settlers calling IDF soldiers Nazis and even kapos, concentration camp overseers often recruited from the Jews themselves.

Ariel himself previously backed a bill to erase convictions from the 2005 disengagement from Gaza and parts of the West Bank. One wonders whether he would be keen to apply his new bill retroactively.

But then again, there is a long and arguably tasteless history of using the Holocaust in Israeli political discourse.

In just a handful of examples, rallies against the Oslo movement in 1995 featured pictures of then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin dressed in SS uniform, and last year, Yaakov Katz of the National Union compared the Eretz Nehederet (“Wonderful Country”) satirical TV programme to Nazi propaganda because of its depiction of religious settlers.

To this day right-wing politicians are fond of referring to the 1967 lines as indefensible “Auschwitz borders”.

To be fair, this phrase was originally coined by the Labour party’s Abba Eban, and this tendency to namecheck the Shoah isn’t restricted to the nationalist right, by any means.

The late great Jewish thinker Yeshayahu Leibowitz caused outrage 30 years ago when he described some Israeli soldiers as akin to “Judeo-Nazis”, and during a joint Israeli/Arab demonstration in Bilin last year, I saw many protestors wearing yellow stars (eight rather than six pointed, but the message was clear) with the word “Palestinian” inscribed in Arabic in the centre.

This exploitation of symbols of the Shoah may be nauseating and an example of deeply cynical manipulation, but it’s a sure way of catching public attention.

Maybe the coalition government sees this bill as a handy way of deflecting the debate away from the real issues at hand – whether that of haredi integration, freedom of speech or faltering social cohesion. It’s certainly likely to win widespread public support.

It’s partly because the Holocaust is such an intimate part of public life in Israel that politicians so freely call those they disagree with Nazis, and civilians judge soldiers drawn from their own ranks to be kapos.

Ariel’s bill aims to control ownership of the Holocaust and its legacy, rather than honour its victims. But using the law to control public discourse in Israeli society, however offensive, is just another shameful exploitation.

Daniella Peled is an editor at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. A former foreign editor of the Jewish Chronicle, she writes widely on Israel and Palestine and is a regular contributor to Ha’aretz