Aseem Trivedi’s arrest for his anti-establishment cartoons shocked and outraged India.

Section 124 of the Indian Penal Code, under which Trivedi was arrested, is reserved for anyone who “brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government,” with disaffection meaning “disloyalty and all feelings of enmity”. Although a majority of Indians found the cartoons crude rather than clever, public opinion overwhelmingly believed the cartoonist was well within his rights to publish them.

Trivedi has since been released on bail, but the incident has triggered debates about future of India’s repressive sedition laws. Even the Mumbai High Court lashed out against the police for arresting Trivedi in the first place, stating: “We live in a free society and enjoy freedom of speech and expression. Sedition is a pre-independence [law]…”

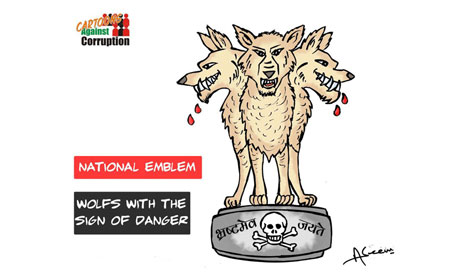

Cartoon by Aseem Trivedi, from cartoonsagainstcorruption.blogspot.co.uk

The complex political layering of India often tosses up headlines where charges of sedition have been levied against persons who, by official accounts, seem to be sympathetic to anti-national elements. Take, for example, the case of Kashmir University lecturer Noor Muhammed Bhat, who was arrested in December 2010 for asking his students to translate the following lines from Urdu to English: “Kashmir is burning again. The blood of youth is being spilled like water. Kids are being beaten to death by police and forces…”. The paper was given to students at a time when the Kashmir Valley was reeling from pro-independence riots in the form of stone throwing from students, sometimes drawing police fire in return.

Bhat also asked students to write an essay on the topic “Are stone throwers the real heroes?”. Bhat defended his actions, saying he was merely drawing from newspapers, and posing a question which students were free to answer as they liked. However, the High Court termed his paper “seditious and rebellious in character.” Bhat was ultimately granted bail and released in January 2011, but not before he was barred from setting or evaluating exam papers for the next five years.

Contrast that with a case in south India this year. About 8,000 people, including children, have been charged under IPC Section 124 for protesting against the planned construction of a nuclear power plant in the fishing village of Idinthakari, Tamil Nadu. Their crime? As a sign of protest, on Independence Day this year, the villagers refused to hoist the national flag, and put up black flags instead.

For the hundreds of academics, teachers, journalists, artists and ordinary citizens who have been charged for sedition on the most dubious grounds, Aseem Trivedi’s predicament might, in the long run, be the turning point. Trivedi wasn’t protesting a particular project in a far corner of the country, nor was he caught up in an extremely contentious political hotbed like Kashmir. He was representing, visually, a frustration with government, politics and corruption that has been best captured by the India Against Corruption movement, of which he is a member. For Indians for whom corruption is today’s most important issue, it was easy to look at Trivedi’s cartoons and decide for themselves if it was really a case of sedition or an anti-establishment protest. There could have been no better trigger for Indians to understand what “sedition” meant and grasp the import of abuse of sedition law.

The court case has inevitably led to debate about sedition laws in the media and courts, highlighting the many others cases where people have been wrongly arrested. Mahatma Gandhi’s famous speech, made when he was charged by the British government for sedition in 1922, has been dug up and quoted by many columnists:

Section 124 A… [is] designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen. Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote, or incite to violence.

Was Lenin Kumar Roy contemplating, promoting or inciting violence when he wrote a book accusing Hindu extremists of violence against minorties in Orissa? Was the Indian state’s controversial charge of sedition against Dr. Binayak Sen, the doctor and human rights activist who worked in the Maoist areas of Chattisgarh, legitimate? Sen, released on bail by the court that did not find enough evidence to support the government’s claim that he had been aiding Maoist rebels, has called the application of sedition “contrary to the spirit of democracy“.

With the media and public-spirited Indians calling for a comprehensive examination and even repeal of the law due to its blatant misuse, it is worth restating that the right to free expression and peaceful dissent is a must for any democracy (freedom of speech is guaranteed as a fundamental right by the Constitution of India, albeit with restrictions). Sedition is a very serious charge that should never be levied against any individual lightly. The situation becomes even more urgent with the internet fast becoming the urban Indian’s vehicle of choice to debate and disagree.

The concepts of sedition and censorship need serious examination.