21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Reports, Index Reports, India, News

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

The rules India makes for its online users are highly significant – for not only will they apply to 1 in 6 people on earth in the near future as more Indians go online, but as the country emerges as a global power they will shape future debates over freedom of expression online.

India is the world’s largest democracy and protects free speech in its laws and constitution.[1] Yet, freedom of expression in the online sphere is increasingly being restricted in India for a number of reasons– including defamation, the maintenance of national security and communal harmony, which are chilling the free flow of information and ideas. Many of the most restrictive laws and technical means used to enforce these restrictions are recent developments that have undermined India’s record on freedom of expression. A mix of social and political pressure, alongside the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008, has led to this decline, but civil society is beginning to push back.

This paper explores the main digital issues and challenges affecting freedom of expression in India today and offers some recommendations to improve digital freedom in the country.

Constraints on digital freedom have caused much controversy and debate in India, and some of the biggest web host companies, such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook, have faced court cases and criminal charges for failing to remove what is deemed “objectionable” content. The main threat to free expression online in India stems from specific laws: most notorious among them the 2000 Information Technology Act (IT Act) and its post-Mumbai attack amendments in 2008 that introduced new regulations around offence and national security.

New regulations introduced in 2011 oblige internet service providers to take down content within 36 hours of a complaint, whether made by an individual, organisation or government body, or face prosecution. This is problematic in many ways: it makes intermediaries liable for content which they did not author on websites and platforms which they may not control and encourages them to monitor and pre-emptively censor online content, which leads to the excessive censorship of content.

Meanwhile, the arrest and prosecution of citizens who have posted content deemed “grossly harmful”, “harassing”, or “blasphemous” has multiplied. Censorship through the criminalisation of online speech and social media usage is troubling, especially when it affects legitimate political comment or harmless content.

Other issues addressed in this paper include how individual states and the national government of India restricts online communications using filters, and increasingly engages in mass surveillance, which can chill freedom of expression. One of the most pressing challenges to digital freedom remains India’s use of network shutdowns in certain regions, it is claimed, in order to prevent public disorder.

Ensuring access to the digital world remains a national challenge. With only 10 percent of the Indian population online today, there may be a billion new Indian netizens online in the future. How India enables this to happen will be a major challenge. While India is an increasingly influential player in global internet governance, now is a critical time to analyse its domestic regulations and policies that will shape the path not only for the people of India but also for regional neighbours and emerging democratic powers.

This paper is divided into the following chapters: online censorship; the criminalisation of online speech and social media; surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data; access to digital; and India’s role in global internet debates.

The online censorship chapter looks at intermediary liability and the issue of state and corporate censorship mainly via takedown requests and filtering and blocking policies. The criminalisation of online speech chapter covers the prosecution of Indian citizens who post content on the net, including on social media.

The surveillance chapter looks at the recent revelations on the extraordinary extent of domestic surveillance online, and how it contributes to chilling free speech online. It also looks at privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data. The access chapter covers obstacles and opportunities in expanding digital access across the country.

Finally, the chapter on India’s role in global internet debates looks at India’s positioning in the current debates that will result in potentially significant changes to net governance in the next two years.

This policy paper is based on research from London and a series of interviews conducted between June and October 2013 with a range of interviewees from civil society, internet businesses, political figures and journalists.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To end internet censorship and provide a safe space for digital freedom, Indian authorities must:

• Stop prosecuting citizens who express legitimate opinions in online debates, posts and discussions;

• Revise takedown procedures, so that demands for online content to be removed do not apply to legitimate expression of opinions or content in the public interest, so not to undermine freedom of expression;

• Reform IT Act provisions 66A and 79 and takedown procedures so that content authors are notified and offered the opportunity to appeal takedown requests before censorship occurs;

• Stop issuing takedown requests without court orders, an increasingly common procedure;

• Lift restrictions on access to and functioning of cybercafés;

• Take better account of the right to privacy and end unwarranted digital intrusions and interference with citizens’ online communications;

• Maintain their support for a multistakeholder approach to global internet governance.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 19 of the Indian Constitution protects freedom of speech and expression. Government of India, ‘The Constitution of India,’ as modified up to the 1st December 2007, Article 19. (1)(a) ‘All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression’ http://lawmin.nic.in/ accessed on 23 September 2013.

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

CONCLUSION

This paper has shown that despite its lively democracy, strong tradition of press freedom and political debates, India is in many ways struggling to find the right balance between freedom of expression online and other concerns such as security. While civil society is becoming increasingly vocal in attempting to push this balance towards freedom of expression, the government seems unwilling or unable to reform the law at the speed required to keep pace with new technologies, in particular the explosion in social media use. The report has found the main problems that need to be tackled are online censorship through takedown requests, filtering and blocking and the criminalisation of online speech.

Politically motivated takedown requests and network disruptions are significant violations of the right to freedom of expression. The government continues its regime of internet filtering and the authorities have stepped up surveillance online and put pressure on internet service providers to collude in the filtering and blocking of content which may be perfectly legitimate.

Despite numerous calls for change, the government has refused to reform the controversial IT Act. However, public outrage and protests against abuses of the law have multiplied since 2012. Civil society and political initiatives against this legislation have increased and demands for new transparent and participatory processes for making internet policy have gained popular support.

Technical means designed to curb freedom of expression, arguably to achieve political gain, have no place in a functioning democratic society. While government efforts to expand digital access across the country are promising, these efforts should not be undermined by disproportionate and politically motivated network shutdowns.

While it is to be welcomed that India is taking a more vocal part in the global internet governance debate in favour of the multistakeholder approach, it is essential it ensures its own laws are proportionate and protect freedom of expression in order for the country to have the most impact in this debate.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To end internet censorship and provide a safe space for digital freedom, Indian authorities must:

• Stop prosecuting citizens who express legitimate opinions in online debates, posts and discussions;

• Revise takedown procedures, so that demands for online content to be removed do not apply to legitimate expression of opinions or content in the public interest, so not to undermine freedom of expression;

• Reform IT Act provisions 66A and 79 and takedown procedures so that content authors are notified and offered the opportunity to appeal takedown requests before censorship occurs;

• Stop issuing takedown requests without court orders, an increasingly common procedure;

• Lift restrictions on access to and functioning of cybercafés;

• Take better account of the right to privacy and end unwarranted digital intrusions and interference with citizens’ online communications;

• Maintain their support for a multistakeholder approach to global internet governance.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

(5) INDIA’S ROLE IN GLOBAL INTERNET DEBATES

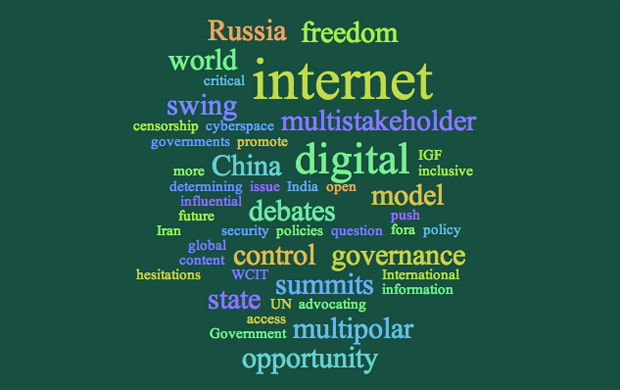

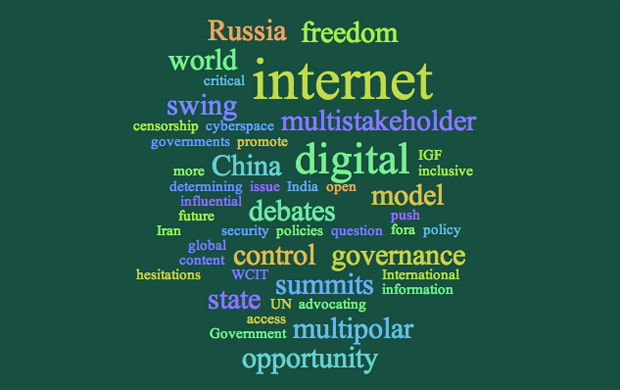

International summits and fora over the next two years will be critical in determining the internet’s future. The open and inclusive multistakeholder model of internet governance has been called into question, with some governments – namely China, Iran and Russia – advocating for more control. As an influential state in our increasingly digital and multipolar world, India has the opportunity to push policies that promote digital freedom. Yet, India is still very much a swing state in these internet governance debates.

After initial scepticism, India has now joined the European Union (EU) and the US in resisting the call for a top-down government-led approach for global internet governance. At the World Conference on International Telecommunication in Dubai in December 2012, India was one of the few countries to side with EU member states and the US in supporting the current multistakeholder status quo. This was the result of a debate in India, in which the key battle line was whether internet freedom constituted a daunting threat to security that required top-down national control or not.

India’s hesitation increased after the 2008 Mumbai attacks when Jaider Singh, Secretary of the Department of Information Technology, described the internet as “both a vehicle and a target of criminal minds”.[49] Concerns over security and spam led India to advocate for more national control over internet governance, through the creation of a United Nations committee.[50] Earlier in 2011 at the Internet Governance Forum in Nairobi, India, along with South Africa and Brazil – two other crucial swing states in the internet governance debate – proposed a similar initiative.

While such top-down control has long been advocated by the likes of China and Iran – countries with a poor domestic track record on digital freedom – it is a direct threat to internet openness and the exercise of human rights online by placing too much control of the process in the hands of national governments. The EU and US tried to address India’s concerns diplomatically by agreeing to a working group.

It is positive that India is now willing to play an important role in defending the multistakeholder model of internet governance against calls for more top-down state regulation. Yet, it is clear that with a sixth of the world’s population, it is not just important for India’s government to defend internet freedom globally, but also ensure that its domestic record stands up to scrutiny and is a model for the rest of the world to adopt. Currently, this is not the case.

India is not only setting internet policies for its 10 percent of users today, but for its 1 billion citizens yet to come online. The decisions it makes, both domestically and on the international stage, are likely to set powerful precedents for regional neighbours, and other emerging democratic powers.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[49] Jaider Singh, speaking at the third annual Internet Governance Forum in Hyderabad, India, in 2008 with the theme ‘Internet for All.’ Internet Governance Forum, ‘Internet Governance Forum Concludes Hyderabad Meeting’ (6 December 2008), http://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/predictions/IGF 08 Daily Highlights Dec 6.pdf accessed on 10 September 2013.

[50] In 2011, India proposed a United Nations Committee for Internet-Related Policies (CIPR) be established to develop and oversee internet policies that would affect the world’s users. Techdirt, ‘India Want UN Body To Run The Internet: Would That Be Such A Bad Thing?’ (2 November 2011), http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20111102/04561716601/india-wants-un-body-to-run-internet-would-that-be-such-bad-thing.shtml accessed on 2 September 2013.

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

4. ACCESS: OBSTACLES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Key concerns in assessing online freedom of expression in India are the barriers to accessing the internet itself. There are a number of major obstacles to online access in India namely infrastructural limitations, cost considerations as well as illiteracy and language. In addition, this section argues that security considerations have created further barriers for Indian people to access the internet.

With around 120 million web users – 12.6 percent of India’s population – internet penetration is relatively low by global standards. Yet as cheaper smartphones enable millions more to access the net, usage is increasing and the government is prioritising digital access and development as a political objective. Digital access initiatives are being developed in India to fight illiteracy and poverty, promote Indian language content online, increase broadband penetration and speed in rural and urban areas, and improve the reliability of electricity.[42]

In May 2006, the government approved a National e-Governance Plan to implement national e-governance with the aim to make all government services accessible to localities. This project aims to connect more Indian citizens through the National Optic Fibre Network and takes into account the need to increase internet access in the country.[43]

One of the major barriers to access online content is language. There are 22 primary regional languages in India, but most online content is in English, a language only 11 percent of the population can read.[44] Civil society initiatives have moved quicker than the government. Journalist Shubhranshu Choudhary has created the news platform CGNet Swara, which lets people use their mobile phone to listen to and leave their own stories, bringing news to communities who don’t speak Hindi or English, and are therefore denied access to mainstream newspapers or news websites.[45]

Broadband access and the price remains a major barrier to digital freedom of expression with only 3% of households having a fixed internet connection in 2012.[46] For this reason, many Indian users access the internet via cybercafés. However in 2011, fearing that cybercafés facilitated criminal and terrorist activities, the Indian Government introduced strict rules restricting cybercafés under Section 79 of the IT Act.

Many have denounced the cybercafé rules as restricting access to cybercafés and infringing Indian citizen’s freedom of expression and privacy rights.[47] The rules are problematic in many ways. Firstly, they limit the creation and sustainability of cybercafés by imposing draconian administrative requirements. For example, cybercafés must also have the capacity to retain user identity information and the log register in a secure manner for a minimum period of a year. Secondly, the rules directly limit citizens’ access to cybercafés. Cybercafés cannot allow users to use computer resources without providing an established identity document, a barrier for poorer people in rural communities who are disproportionately likely not to have the required identification.

India faces numerous obstacles to internet access, from infrastructural limitations to costs and language restrictions.[48] While government efforts to increase broadband penetration and speed in rural and urban areas are welcome, restrictions on access to and the functioning of cybercafés must be lifted.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[42] Hari Kumar, New York Times, India Ink (Blog), ‘In India Homes, Phones and Electricity on Rise but Sanitation and Internet Lagging’ (14 March 2012), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/in-indian-homes-phones-electricity-on-rise-but-sanitation-internet-lagging/ accessed on 11 September 2013.

[43] Government of India, National e-Governance Plan, http://india.gov.in/e-governance/national-e-governance-plan

[44] OpenNet Initiative, ‘Country Profile: India’ (9 August 2012) https://opennet.net/research/profiles/india accessed on 10 September 2013.

[45] Rachael Jolley, Index on Censorship, ‘India calling’, ‘Not heard? Ignored, suppressed and censored voices’, Volume 42, Number 03, September 2013.

[46] Hari Kumar, New York Times, India Ink (Blog), ‘In India Homes, Phones and Electricity on Rise but Sanitation and Internet Lagging’ (14 March 2012), http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/in-indian-homes-phones-electricity-on-rise-but-sanitation-internet-lagging/ accessed on 11 September 2013.

[47] Information Technology [Guidelines for Cybercafés] Rules, 2011, http://deity.gov.in/sites/upload_files/dit/files/GSR315E_10511(1).pdf accessed on 11 September 2013.

[48] Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the net 2013’, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2013/india accessed on 4 October 2013.