15 Oct 2013 | Magazine, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including Not heard?.

Subscribe now.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Oct 2013 | News, Syria

Paul Conroy at a protest in London last year calling for peace in Syria. Image Demotix/Russell Pollard

Journalists have a bigger influence on how war is perceived than in years gone by, said war photographer Paul Conroy at the Cheltenham Literature Festival yesterday.

Discussing how journalists and photographers cover wars and the pressures they are under, Conroy, who covered Syria with Sunday Times journalist Marie Colvin, said: “Everything is in the instant now, battles have been influenced by the immediacy of information.”

Conroy described how he and Colvin got into Syria using underground tunnels and the assistance of rebels. They were smuggled into Syria through a 3km scramble down a storm drain, which he described as “the only way”. He added: “The risks were quite high.”

He also talked about the attack on the media centre they were operating from, which killed Colvin. Conroy, who was badly injured, was rescued and got out of the war zone so he could be treated.

When asked about how newspapers’ tightening budgets were affecting foreign new coverage, Sunday Times associate editor Sean Ryan, who was chairing the event and was Conroy and Colvin’s desk contact, said: “We will always cover the biggest conflicts.” Conroy called for more funding for foreign news coverage from the media in general.

The acclaimed war photographer, who also covered the Balkan conflicts, said it was now impossible for journalists to switch from being with one side to covering the other side of a conflict. It had been possible in the 1990s, but this was no longer the case.

Because of this journalists had to be wary of how they might be used to put forward a biased or inaccurate picture. “What we realised was that you are open to be used for propaganda. What you have to do is double check and get eye witness accounts.”

14 Oct 2013 | United Kingdom

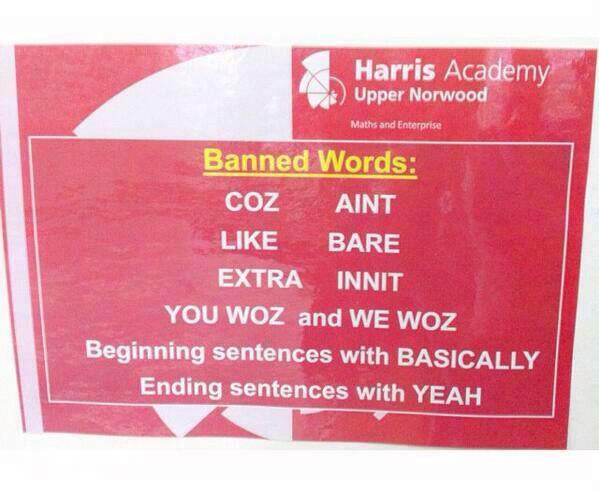

A London school has produced a list of phrases students are banned from using.

As opposed to Liverpool Football Club, who back in July issued their own list of “unacceptable words”, the Harris Academy in Upper Norwood doesn’t appear to be trying to tackle offensive language. Rather, they are standing up for Proper English, with banned words including “like’”, “bare” and “innit”.

It seems their desire to develop “articulate, perceptive and empathetic global citizens” is impeded by students beginning sentences with “basically”.

See the whole list below, via @_griff

This article was edited at 4:39 pm on 14 October 2013. The original version mistakenly linked and quoted the Harris Academy South Norwood website.

11 Oct 2013 | Digital Freedom, News, Politics and Society

Photo: Flickr user Secretary of Defense

A threat to press freedom is an assault on our right to know.

A new report from the Committee to Protect Journalists tries to capture the invisible impact of the Obama administration’s troubled relationship with the press. The report, authored by Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of the Washington Post, and CPJ’s Sara Rafsky, is the most comprehensive look at how the Obama administration’s actions have deeply damaged press freedom and the public’s access to information.

For those who have followed the administration’s policies, court cases and actions related to leaks and the press, the report doesn’t contain a lot of new information. What it does is weave together each of the cases and strategies the administration has pursued, surfacing key themes and illustrating that these examples are not aberrations, but part of a coordinated strategy. Presenting this bigger picture reframes the debate over press freedom in America and reminds us that it’s not enough to tinker around the edges; we need to demand a major course correction.

The report covers the administration’s leak investigations and policies, its surveillance programs, its secrecy and the use of its own media channels to evade “scrutiny by the press.”

All of this is punctuated by the interviews Downie conducted with journalists. Hearing from journalists in their own words, about the challenges they’ve faced and the concerns they have, brings home the seriousness of the crisis in press freedom.

New York Times National Security Reporter Scott Shane captured it best when he told Downie that sources are now “scared to death” to even talk about unclassified, everyday issues.

“There’s a gray zone between classified and unclassified information, and most sources were in that gray zone. Sources are now afraid to enter that gray zone,” Shane said. “It’s having a deterrent effect. If we consider aggressive press coverage of government activities being at the core of American democracy, this tips the balance heavily in favor of the government.”

That shifting balance of power is one of the critical takeaways from the CPJ report. Through efforts like NSA surveillance, the Justice Department’s seizure of phone and email records, and the “Insider Threat Program,” which encourages federal employees to monitor the behavior of their colleagues, the Obama administration has marshaled institutional resources toward efforts that erode press freedom and challenge newsgathering.

“The administration’s war on leaks and other efforts to control information are the most aggressive I’ve seen since the Nixon administration,” Downie writes. “The 30 experienced Washington journalists at a variety of news organizations whom I interviewed for this report could not remember any precedent.”

The report is an important addition to the debate about press freedom, but the scope of its inquiry is limiting. In focusing on the Obama administration, Downie examines in depth the various cases of journalists who have been caught up in federal investigations and the actions of federal agencies only.

As such, the report is not a full accounting of the state of press freedom today. A more comprehensive analysis of troubling state bills, worrisome court cases and the alarming spike in journalist arrests and harassment by local police would give a fuller picture.

In addition, the journalists implicated in the cases Downie reports on are all from mainstream media organizations like the Associated Press, Fox News and the New York Times, and most of his interviews are with Washington editors and reporters from major newsrooms. But the Obama administration’s adversarial relationship with the press has also impacted smaller newsrooms, freelance journalists, independent bloggers and citizen journalists.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has led the way in looking at the impact of threats to press freedom and freedom of expression on digital journalists and citizen reporters abroad. This report should be a starting place for the CPJ to assess the threats and challenges facing all kinds of journalists in the U.S.

It’s notable that, in its recommendations at the end of the report, CPJ calls on the Obama administration to “advocate for the broadest possible definition of ‘journalist’ or ‘journalism’ in any federal shield law.” The law, the CPJ says, must “protect the newsgathering process, rather than professional credentials, experience, or status, so that it cannot be used as a means of de facto government licensing.”

While the CPJ focuses here on the need for a shield law, this recommendation should apply to any law or guideline the administration implements. The shield law is important not only for how it defines a journalist but also for the precedent it could set for future press freedom decisions.

The CPJ also advocates for ensuring that journalists won’t be prosecuted for receiving or reporting on leaks, ending the use of the Espionage Act to prosecute those who leak information to the press, improving transparency about NSA surveillance, enforcing revised Justice Department guidelines, ending the use of overly broad secret subpoenas, and strengthening the administration’s adherence to the Freedom of Information Act.

It’s remarkable that we have to ask for these basic protections and reassurances from our government, but the CPJ report makes it clear that we can’t take press freedom for granted. This report should be a starting point for a much larger discussion that brings together journalists of all kinds, policymakers and everyday Americans to talk through the challenges, questions and concerns about press freedom.

We’re facing a fundamental and coordinated shift in how our government and press interact — and it’s not enough to respond to each attack in isolation. We need to launch a proactive effort to reassert the centrality of a free press in our democracy.

This article was originally published at FreePress.net and is republished here by permission.