11 Feb 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News and features, Politics and Society, South Korea

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

South Korean prosecutors currently seeking a whopping 20 years imprisonment for lawmaker Lee Seok-ki on charges including praising North Korea. On 3 February, the Korean Supreme Court overturned a partial acquittal of a man charged with praising North Korea; that same day a 74-year-old man was given a sentence of two-and-a-half years for similar activities. On 28 January a man was sentenced to ten months in prison for posting pro-Pyongyang messages in an obscure online cafe.

These are some of the latest in a spate of recent cases which indicate that the South Korean government is more strictly enforcing its controversial National Security Law (NSL). Article 7 of the law long criticised as an unjust limit to freedom of expression, prescribes legal punishment for “any person who praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organisation”. What constitutes praise, incitement or propagation is not clearly defined.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say the threat of North Korean infiltration is exaggerated and the law is really meant to stifle dissent within the country. Amnesty International said the NSL is “increasingly and arbitrarily used to curtail freedoms of association and expression”, while the United Nations special rapporteur for human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya, described the NSL as “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Recent years have seen cases where seemingly innocuous conduct led to criminal prosecution, notably the case of Park Jung-geun, who was indicted in 2012 on criminal charges for retweeting messages from North Korea’s official Twitter account. Between 2008 and 2011, the number of NSL cases shot up by 95.6 percent, according to an Amnesty report released in December 2012. Last year 103 people were charged with violating the law, the highest figure in ten years.

The charges against Lee Seok-ki were laid in spring of last year when Seoul and Pyongyang were engaged in a war of words that had many wondering if actual war was imminent. The main charge against him is making plans to help North Korea win in the event of a war. However, he is more likely to be convicted according to the NSL for praising North Korea at a meeting, referring to North Korea’s leadership using honorific titles. To be convicted of assisting North Korea during a war prosecutors would have to show that Lee’s plans were practicable, which is unlikely.

The NSL was instituted in the late 1940s, in the time between Korea’s colonial occupation by Japan and the start of the Korean War, ostensibly to protect South Korea from infiltration by North Korean spies. The combat phase of the Korean War ended with an armistice agreement in 1953, but no peace treaty was ever put in place, so the two countries technically remain at war. This enduring state of conflict has meant that the NSL has remained on the books as a limit to freedom of expression.

Throughout nearly all of its history, South Korea has been governed under something like a state of emergency, with the government arguing that due to the threat posed by North Korea, civil liberties needed to be suspended to maintain security and allow for economic development.

Last April, the country’s top legal authority, Justice Minister Hwang Kyo-ahn, defended use of the NSL in an interview with JTBC television. Hwang argued that pro-North Korea forces are plentiful in the South and that the NSL was needed as protection, saying: “A special kind of law is needed to defend against this special kind of crime”.

What Hwang didn’t mention is that the groups that voice these kinds of pro-North Korea statements are tiny, fringe outfits that almost no one takes seriously and have never had any real success. Critics say criminalising their statements only lends them an undue air of seriousness.

President Park Geun-hye and her cabinet are not a free speech-loving bunch, and are in office at a time of tense relations with North Korea, meaning that pro-North Korea activities are being taken seriously. Park herself is daughter of former South Korean president Park Chung-hee, a military dictator who suspended civil rights including freedom of speech in the name of national development.

The increased use of the NSL shows the durability of this logic, and the South Korean government’s steady position [means that] freedom of expression can be limited in the name of vague national objectives.

This article was posted on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News and features

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the second of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform.

The present media market started to take shape at the beginning of 1990s as Belarus became an independent state after the Soviet Union disintegrated. Unlike other post-Soviet states, the process of the denationalisation and privatisation of the state media was not in fact ever launched leaving state control and ownership over most of national media. While a number of independent media outlets were established in the 1990s, very few have managed to survive.

Current media are significantly affected by the political and economic situation after the presidential election of December 2010 that was followed by a severe clampdown on political opposition and civil society and periods of financial instability.

The authorities keep tight regulatory and economic control over the news media market. State-run media that are used as means of government propaganda enjoy significant financial support, while independent news media face economic discrimination that makes their position in the market more vulnerable.

Broadcast media

Broadcast media remain the primary source of information for most Belarusians. The overall reach of television is 98.4% of the population aged over 15, and its share in the media advertising market is over 50% of the total. This dominant position of television is the reason the state keeps this sphere under strict control. Most of broadcast media in Belarus are state-owned, and they enjoy significant financial support from the authorities. The state budget of Belarus for 2014 allocated 548 bn roubles (about £34m) for direct support of television and radio.

There are 262 TV and radio stations registered, 178 of them–68% of the total–are owned by the state. There is no formal Public Service Broadcaster (PSB) with an independent board and a commitment to impartiality. Four national channels are owned by the National State Television and Radio Company which also owns five radio channels and five regional TV and radio companies. Two more national channels, ONT and STV, are formally joint stock companies, but they are not publicly listed, and all their founders are state companies.

There is not a single independent national TV channel or a public service broadcaster in the country. Independent broadcast media that operates from abroad face restrictions. For instance, Belsat TV channel, which has been broadcasting in Belarusian from Poland since 2007, has been refused permission to open an official editorial office in Belarus. Belsat’s reporters face constant pressure and are subjected to warnings and detentions.

At the same time, a decision taken in November 2013 to prolong accreditation in Minsk of the editorial office of Euroradio, an independent radio station that also broadcasts in Belarusian from Poland, can be considered as a positive step.

The general process of licensing and frequency allocation in Belarus is complicated, not transparent and is controlled entirely by the government through licensing and frequency allocation processes.

Printed media

Economic leverages are used by the authorities of the country to control the printed news media market in Belarus. While state-owned newspapers have preferences in advertising market and distribution, independent publications fail to enjoy equal conditions, being restricted from distribution systems and advertising. Economic difficulties threaten operations of non-state socio-political newspapers, and thus restrict the access of the audience to independent sources of information.

The majority of printed media – 1,146 out of the total of 1,556 registered in Belarus as of 1 January 2014 – are privately owned. Most of the non-state newspapers are not news publishers but mainly advertising or publications for entertainment. According to BAJ, there are less than 30 socio-political newspapers, both national and regional, in Belarus that are publications with actual news journalism.

There is a significant amount of evidence to suggest that the non-state owned press in Belarus faces economic discrimination. Direct state subsidies to the state-owned printed media in 2014 are projected to be 64 bn roubles (about £4 m). It is claimed by the editors of several non-state newspapers, that the costs of paper and printing for independent newspapers are higher than for state-owned ones.

Another form of direct economic discrimination by the government is the influence of the state over the advertising market. The economy of Belarus is dominated by the state, with 70 per cent of its GDP being the output of state-owned companies. In practice this gives opportunities for the direct interference of the government in the distribution of advertising revenues. It is also the case that there is compulsory subscription to state-owned newspapers, both national and local, for employees of state-owned enterprises and organisations.

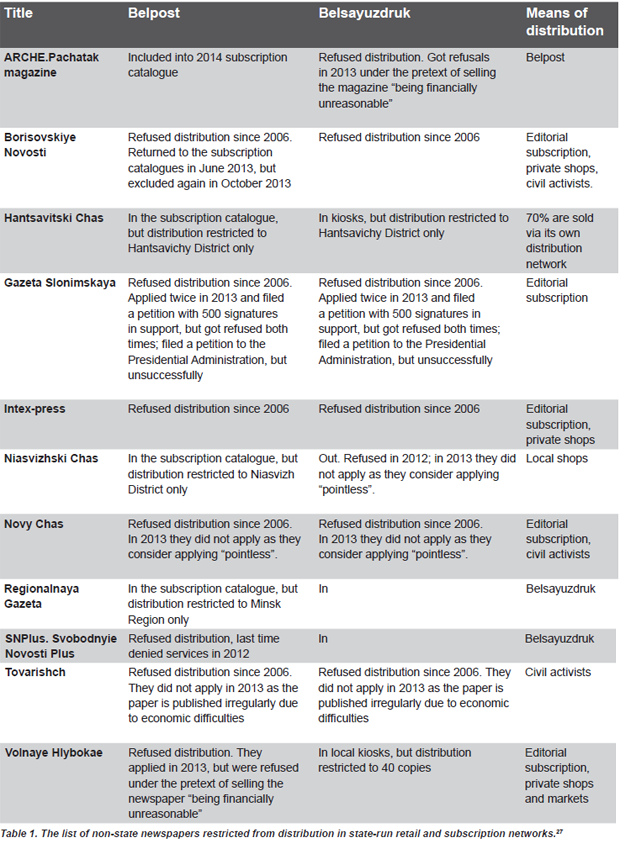

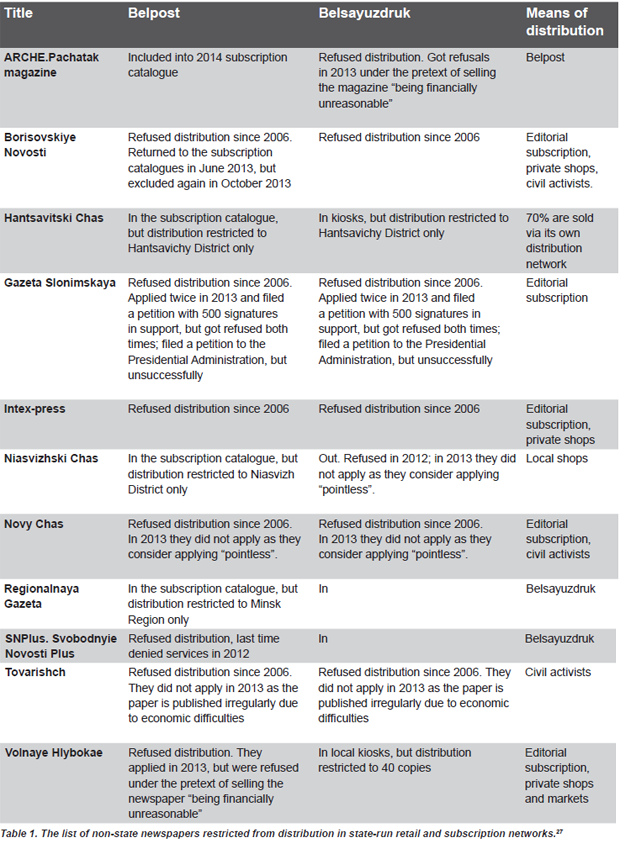

There is direct state intervention in the distribution of independent newspapers, which prevents their sale. At least eleven independent publications face restrictions to their distribution via state-run retail press distribution and subscription networks (Table 1). The distribution ban was imposed on the eve of the presidential election of 2006, when at least 16 independent newspapers were excluded from the subscription catalogue of Belposhta (Belarusian Post) and 19 had their contracts with Belsayuzdruk retail sales system cancelled. Due to the distribution restrictions several of them ceased to exist. Most of those that survived remain barred from state distributors and have had to either develop their own distribution systems or move completely online.

The authorities of the country persistently refuse to acknowledge the problem of distribution restrictions. Dzmitry Shedko, Deputy Minister of Information, wrote to Index request that “non-state media equally with state ones have a free access to state printing facilities and possibilities to distribute their publications through state press distribution structures.” The Deputy Minister points out that the law provides for the freedom of contract, and the authorities cannot interfere with the will of distribution companies to sign contracts with any particular mass media outlet.

In practice the reality is very different. In 2008 two independent newspapers, Nasha Niva and Narodnaya Volia, were returned to state distribution systems as a part of commitments the authorities of Belarus made to the European Union in order to re-launch a political dialogue with the EU. It proves a decision to lift the distribution restriction is political and can be dictated by the state.

Online media

The internet in Belarus is developing extensively, although it cannot still boast of the same audiences as broadcast media. Over 4.85 m Belarusians aged over 15 access the internet–12% more than a year ago–and over 80% of those with access go online every day. Sixty-eight percent of Belarus’s internet users go online through a high-speed broadband connection. The internet remains a relatively free domain of freedom of expression in the country, despite recent attempts by the government to put it under tighter control, as revealed in Belarus: Pulling the Plug report, produced by Index on Censorship in January 2013.

Growing internet penetration and the restrictions traditional media face offline has led to a significant development of online news media. For instance, several independent publications that stopped issuing printed versions due to distribution restrictions now only exist as websites. This is the case with Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta, once one of the leaders of non-state press, Salidarnasc or Khimik regional newspaper. Online versions of several existent newspapers reach a larger audience that their printed versions.

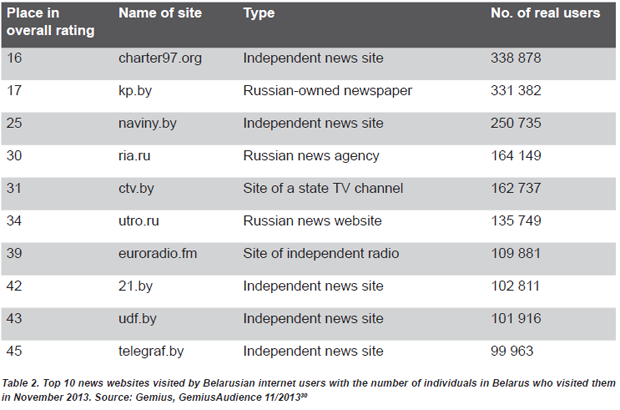

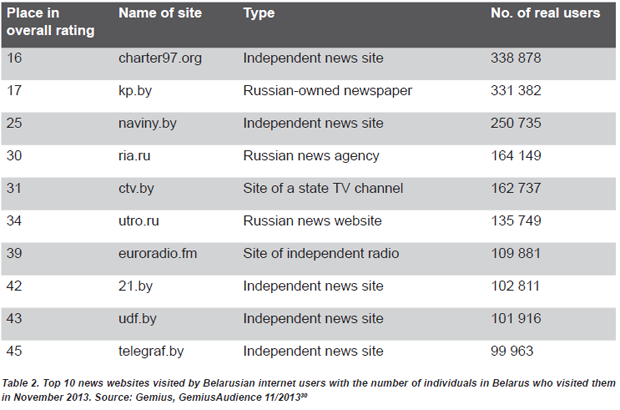

In general, independent online publications enjoy significantly greater popularity among internet users than pro-regime websites of state-run media.

This table represents online news publications only, but does not include the news sections of larger internet portals. It should be noted that they are much more popular then dedicated news publications. For instance, the news section of the largest Belarusian portal TUT.BY is visited by about 1 m Belarusians aged over 15 monthly. News sections of major Russian portals Mail.ru and Yandex.ru are ranked 2nd and 3rd as sources of online news for visitors from Belarus.

The two important trends of Belarus’s online news market are:

• Dedicated news websites are not the most popular online destinations for Belarusians;

• Russian websites have a significant market share in terms of Belarusian audience.

The top 20 news publications have a joint reach of no more than 25% of the total number of Belarusians online. If news sections of major portals are taken into consideration, this share is still around 45%. At the same time, Mail.ru, a Russian portal that is the most popular website among the Belarusian audience, has an audience share of 61.7% alone. Users appear to favour reading news on portals, where they can get other services and on news aggregators.

Social media sites are visited by 72.5% of Belarusian internet users, with Russian Odnoklassniki.ru and Vkontakte leading in this group as well. Four of the six most popular websites in Belarus are Russian portals or services.

There are serious limitations to the development of the online news media market. This is not due to government restrictions, but primarily due to economic factors. The total annual volume of the online advertising market in Belarus in 2013 is estimated to be $10.5 million US dollars. Despite 50% growth to 2012, Belarus still has one of the lowest advertising expenditure budgets per internet user in Europe. The market is very much dominated by its leaders, including Russian media companies that have significant resources to expand and currently enjoy a significant market share.

Case study: State and non-state press: Different media realities

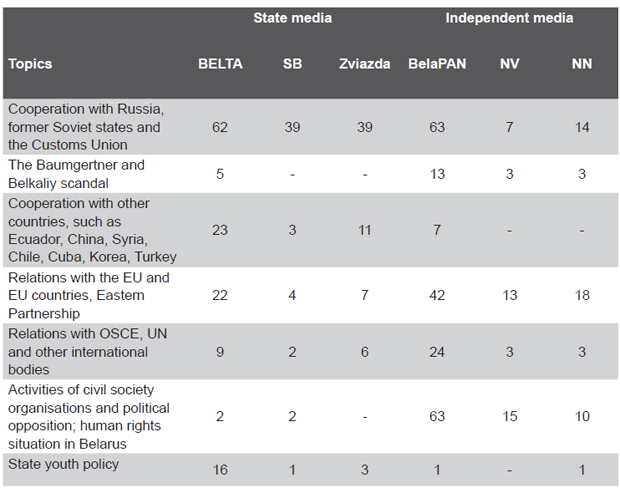

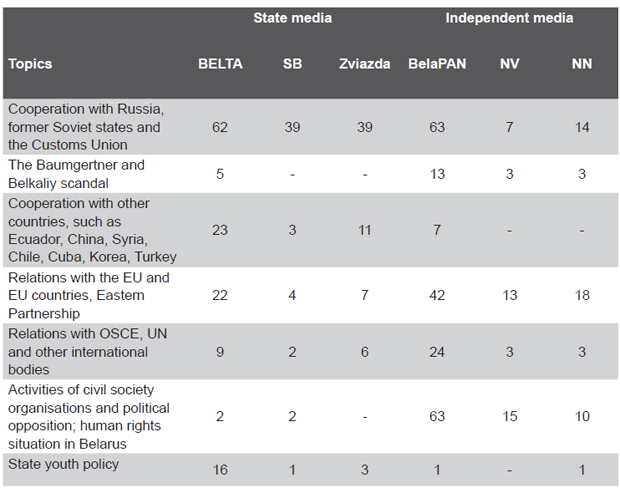

Index on Censorship in cooperation with Mediakritika.by, a Belarusian project dedicated to analysing and monitoring the national media landscape, conducted field research into the content published by state-owned and independent media (that is privately owned media that is free from political direction from the president and government). The research found clear differences between editorial policies of the media based on their ownership including the topics they cover and their approaches to coverage. The difference was particularly noticeable during major political campaigns, such as elections.

The research looked at the content of six Belarusian media outlets, analysed as presented at their websites in October 2013. They are two leading information agencies, state-owned BELTA and privately owned BelaPAN (presented online as Naviny.by), and four national newspapers, state-owned Sovetskaya Belorussiya (SB) and Zviazda, and independent Narodnaya Volia (NV) and Nasha Niva (NN).

The content was analysed in terms of presence of several specific topics (quantitative) and the way they were approached by the media (qualitative). The table below represents the number of articles covered or mentioned by the specified topics from the respective media outlets in October 2013:

On the first category, the coverage of relations with states from the former Soviet Union and the creation of a Customs Union (between Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan) which is part of the official foreign policy of Belarus, the state news agency BELTA dedicates significant coverage. BELTA also gives significant coverage to successful foreign policy partnerships by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and countries in South-East Asia and Latin America. The state media’s significant coverage of the Customs Union and relations with Russia is not matched by coverage of Belarus – EU relations. The analysis found there was little coverage of foreign policy analysis except the opinions of state officials.

The independent media also pays significant attention to the Russian – Belarusian relations, but there is significantly more coverage of Belarusian relations with the EU and other international institutions and organisations. For example, the number of news items on the “eastern” and “western” vectors produced by BelaPAN is almost the same; BELTA pays twice more attention to ex-Soviet countries, Russia first of all, than to cooperation with the West.

Even more dramatic differences are noted in the way state and independent media cover domestic politics. Within the state media politics is associated with (and consists of little more than) the statements and public speeches of the President. State media outlets even have “President” as a separate news section. BELTA’s “President” section, for instance, had more than 80 news items on activities and statements of the head of the state in October 2013.

The most significant difference between the state-owned media and the privately owned media is that there is almost no mention of the activities of the political opposition, while the independent media provides significant coverage of the activities of opposition political parties but also independent trade unions, civil society organisations and activists.

Human rights issues or repressive measures taken by the authorities are widely covered by the independent media. As can be seen in the table, the state media almost entirely ignores these issues. While the recent scandal with Vladislav Baumgertner, the CEO of the Russian Uralkaliy company, who was arrested in Minsk,34 generated significant headlines in the independent media in Belarus – and the media in Russia as well – it was hardly covered by the Belarusian state media; their coverage was reduced to quotes from President Lukashenko on the matter.

There have been no visible improvements of the situation with traditional news media since 2009 in Belarus. The state keeps dominating the broadcast media market and preserves tight control over printed publications. State-owned media are used as a tool for government propaganda, while independent socio-political press faces discrimination that limits their operational capacity and thus restricts the development of free and pluralistic media in the country. The internet re-shapes the news media market as it provides new opportunities for free flow of information and ideas, but its full-scale development as a free speech domain is hindered by economic peculiarities and attempts of state regulation.

Belarus media landscape: Recommendations

All forms of economic discrimination against non-state independent press should be eliminated, in particular:

• independent publications should be treated equally by the state system of press distribution and Belposhta subscription catalogues;

• the state has a pro-active duty to protect and promote freedom of expression and so should investigate anti-competitive practices including the charging of unequal prices for paper and the distribution services for publications for different types of ownership.

Reforms of the Belarusian media field should be launched, including de-monopolising of the electronic media, introducing public service media and creating a competitive media market. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News and features

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the first of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform

Belarus continues to have one of the most restrictive and hostile media environments in Europe.

Despite pressure from international sources recent years have brought no genuine improvements to the media situation. In a country that has not held a free or fair election since 1994, the authorities keep tight control over the media as a means of preserving their power.

The country’s media market is strictly controlled by the Belarusian government. That control rigs the media market to benefit state-owned providers and impedes the development of independent print and television outlets through legislative and administrative restrictions. The state-owned media enjoys significant budget subsidies, favourable advertising and distribution contracts with government agencies. In comparison, independent publications face economic discrimination and distribution restrictions. Field research conducted for this policy paper in Belarus found clear differences between editorial policies of the media based on their ownership including the topics they cover and their approaches to coverage.

The internet has become an important source of independent information for Belarusians. The development of online news media is hindered by the structure of the internet market, which is dominated by large portals and services, including many Russian sites. Belarusian authorities also aim at tighter regulation of internet as outlined in Index’s policy paper, Belarus: Pulling the Plug.

Restrictive media legislation and its oppressive implementation has made the media landscape unfavourable for freedom of expression. Media law forces new outlets to register and regulations give the state the power to close down media even for minor infringements. Accreditation procedures are used to restrict journalists’ access to information and foreign correspondents face additional obstacles in reporting from the country. The criminalisation of defamation, anti-extremism legislation and other laws are being used to curtail media freedom and persecute independent journalists and publishers. The police use violence and detain journalists, especially those who cover protests. Reporters are routinely sentenced to administrative arrests and fines.

Despite ongoing pressure by international bodies such as Index on Censorship, the authorities of the country have been quite reluctant to discuss or implement recommendations on media legislation or changes in practices of their implementation to bring them in line with international standards.

Index urges the Belarusian authorities to immediately remove all contraventions of human rights and media freedom. The much-needed reforms of the media field should be launched in order to end harassment and persecution of journalists, and eliminate excessive state interference in media freedom. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.

The European Union and other international institutions must place the issue of media freedom on the agenda of any dialogue with the Belarusian authorities to demand genuine reforms to bring the Belarus media-related legislation and practices of its implementation in line with the Belarusian Constitution and its international commitments in the field of freedom of expression.

****

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press is guaranteed in the Belarusian Constitution. But despite the authorities of the country stating it “has a full-fledged national information space” that “develops dynamically”, the country is one of the world’s worst places for media freedom. Belarus is listed 193 out of 197, lowest in the 2013 Freedom of the Press rating by Freedom House. Reporters Without Borders rank it 157 out of 179 countries in their 2013 Press Freedom Index.

According to Thomas Hammarberg, a former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, “free, independent and pluralistic media based on freedom of information and expression are a core element of any functioning democracy; freedom of the media is also essential for the protection of all other human rights.”

The media freedom situation and the form of the Belarusian media market are affected by the overall political situation. The media field is tightly regulated by the authorities of the country that see close control over the information sphere as their basis of preserving power. Belarus is described as “not free” in terms of political freedoms and is criticised for its overall poor human rights record. No election or national referendum in Belarus has been recognised as free and fair by OSCE ODIHR since President Alexander Lukashenko came to power in 1994. According to Belarusian human rights organisations, there are currently 11 political prisoners behind bars. The report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus suggests there are serious problems with freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, freedom of association and other fundamental rights and freedoms.

Serious concerns over profound and systemic problems with media freedom in Belarus have been highlighted on numerous occasions by the European Parliament, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, as well as civil society within the country.

“The Belarusian independent media fulfil a crucial role in the state dominated media landscape in Belarus and have been one of the main victims of the authorities’ crackdown on independent opinions after the 2010 Presidential elections,” said the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policy Štefan Füle.

The main areas of concern are the restrictive legal framework, issues of impunity and journalists’ safety as well as the ongoing economic discrimination by the state against independent media.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 10 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Feb 2014 | Egypt, News and features

With much anticipation, Egyptians huddled around their television sets on Friday night to watch their favourite comedian, Bassem Youssef, make his debut appearance on the Saudi-funded MBC Misr Channel after a three-month absence from the small screen.

Youssef’s fans were not disappointed: They were treated to a full hour of non-stop laughter as the satirist, often compared to US comedian John Stewart, took jibes at the current state of the media and at the Egyptian public’s infatuation with defence minister field marshall Abdel Fattah El Sisi. Youssef cracked jokes about how everything in the country revolves around El Sisi whose name crops up on practically every TV show including cookery and sports programmes.

Youssef opened the show with a pledge not to talk about “sensitive political issues” that had previously caused his satirical show Al Bernameg, The Programme, to be pulled off the air by the management of the privately-owned Egyptian CBC satellite channel. Minutes later, he reversed his decision. “What are we going to talk about?” he asked his studio audience before throwing caution to the wind and starting to poke fun at the Sisi-mania gripping the country. He stopped short however, of taking aim at El Sisi himself, making no secret of the fact that such action would provoke a negative response from the censors.

” It’s better we don’t mention him,” he said as a silhouette- image of the military chief appeared on the screen . “Not out of fear but out of respect,” he sarcastically retorted.

Youssef’s show Al Bernameg was suspended last October following a controversial episode that CBC administrators said had “violated editorial policies and caused discontent among viewers.” In that episode–his first appearance since Islamist president Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests in July– Youssef had poked fun at the Egyptian public’s blind idolisation of General El Sisi, widely expected to become the country’s next president. That had been enough to land him in trouble.

Not only was the show pulled off the air, but Youssef was also lambasted mercilessly by pro-military supporters in both the traditional media and social media. The attacks on Youssef did not stop there: Criminal charges were brought against him by angry citizens who accused him of “insulting the military.”

The legal complaints lodged against Youssef in November were not the first time the popular satirist had been indicted. In March 2013, he was investigated by the public prosecutor on a set of charges ranging from “insulting Pakistan” to “spreading atheism” and “insulting Islam and the president.” The accusations against him were triggered by his persistent ridiculing of then-president Mohamed Morsi. In an episode of the show early last year, he appeared on the set wearing a gigantic hat similar to one worn by Morsi when he received an honorary doctorate from a Pakistani university. Youssef’s unabashed lampooning of the former president delighted the former president’s opponents while earning Youssef the wrath of his Islamist supporters.

Youssef was not convicted. After an investigation lasting five-hours, he was released on $2,200 bail and went right back to mocking Morsi.

His indictment triggered an international outcry, raising concerns over regression on the country’s hard won freedom of expression and press freedom. Little did anyone –let alone Youssef himself who later joined the June 30 protests demanding the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime—suspect at the time that those freedoms would be further undermined and eroded by the military-backed regime that would replace Morsi three months later.

Since Morsi’s ouster, restrictions on the press have been even “greater than those imposed by either Morsi or his predecessor, autocrat Hosni Mubarak”, lament press freedom advocates and media analysts. The intimidation and harassment of journalists including increased physical assaults on them by security forces and by ordinary Egyptians supportive of the military, have raised concerns about the safety of journalists working in Egypt and press freedom in the country.

The indictment of 20 journalists – four of them foreign correspondents—has fuelled fears of a widening crackdown on journalists critical of the military-backed government. Eight of the defendants are journalists working with the Al Jazeera network –four of whom languish in prison on charges of “spreading false news and assisting or belonging to a terrorist organization.” Similar charges have been leveled against the sixteen other defendants in the case including Dutch journalist Rena Nejtes who last week, managed to flee the country, escaping arrest.

Sue Turton, one of two British defendants in what has come to be known as the “Al Jazeera case” told CNN on Friday that “the crackdown by the Egyptian authorities was targeting all journalists who do not tow the government line. ” She and fellow British defendant Dominic Kane are safely out of the country unlike Australian award-winning journalist Peter Greste who has been behind bars for six weeks. On Sunday, his parents made an impassioned appeal to Egyptian authorities for his release. Speaking to journalists in a press conference in Cairo, they described the accusations against him as “bizarre” and “ludicrous.” Juris Greste , Peter’s father, insisted his son’s detention was ” unfair and unjustifiable,” and urged prosecutors to release him immediately.

In a worldwide campaign to press for the release of the four Al Jazeera journalists, fellow-journalists from different countries across the globe have expressed solidarity with the defendants. They posted their own pictures on social media networks—with their mouths plastered ” to symbolize the Egyptian regime’s gagging of the press,” one campaigner explained via her Twitter account.

The detention of the Al Jazeera journalists is having a chilling effect on journalists working in Egypt, forcing many local journalists to practice self- censorship for fear of potential government reprisals. Others have fallen silent.

In the current hostile environment , it is not surprising that Youssef too is uncertain if he will be allowed to continue broadcasting his show. Wrapping up Friday’s episode, he asked “Second episode ?” before bursting out laughing. In the country’s repressive climate, no one can predict what might happen next.

This article was posted on 10 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org