13 Nov 2014 | Index Reports

Ahead of tonight’s event The Artist and The Censor, we’re reposting our 2011 study about the policing of free expression.

The policing of freedom of expression is the story within the story within the story in this case study. In 2004, Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti (Dishonour) was cancelled after demonstrations against it turned violent and its staging was deemed a threat to public order. Her subsequent play Behud (Beyond Belief) is a response to these events, exploring the tensions between public order and freedom of expression. The dialogue between the theatre and the police in the lead up to the premiere of Behud in 2010 is a principle feature of this case study. Julia Farrington is an associate arts producer at Index on Censorship

Download report here

Beyond Belief COMPILED v5

13 Nov 2014 | Draw the Line, Events

The general elections in the UK next May means that the topic of voting and who should be able to vote is under scrutiny, and students at Lilian Baylis Technology School in south London found that there were few clear cut answers.

Index visited the 6th form of Lilian Baylis yesterday to host our latest Draw the Line workshop where we asked the student to examine the question “Are voting restrictions a free speech violation?” in a number of ways. The discussion ranged from the issue of 16 year olds and prisoners voting in the UK, to voting restrictions in different countries including gender, age, level of education, military and mental disability.

![IMG_0965[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09651-1024x768.jpg)

The session concluded in a debate on whether 16 year olds be allowed to vote. The group in agreement pointed out that at 16 you are able to join the army and therefore die for your country, but have no way of directing its political activity. They also argued that although 16 and 17 years old can’t vote now, the outcome of the next election will affect them when they are 18 and for the following few years. As one participant said, tuition fees went up after the 2011 general election, but the 16 year olds who were later affected by this change had no say in it.

The team who disagreed highlighted the fact that 16 year olds are not deemed responsible enough to buy alcohol, see certain films or buy certain video games so they are not responsible enough to vote. They also suggested that many 16 year olds don’t understand politics and therefore shouldn’t be able to take part in the political system.

![IMG_0966[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09661-1024x768.jpg)

Ultimately, however, both groups agreed they should get the chance to have their say who will control their future.

If you would like to get involved you can follow the debate on our Draw the Line discussion page and tweet your own thought using #IndexDrawtheLine.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Nov 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Politics and Society, Russia, United Kingdom

(Photo: Padraig Reidy)

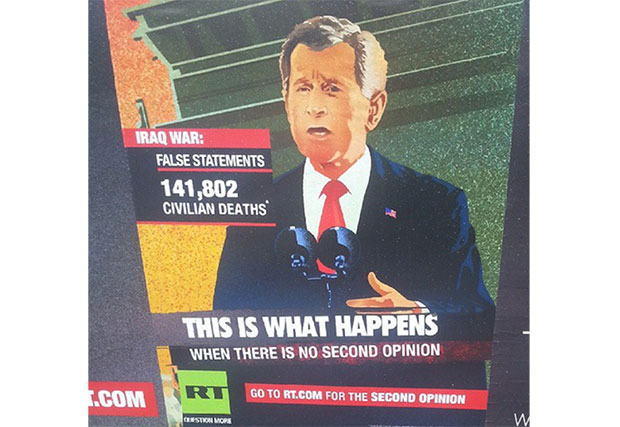

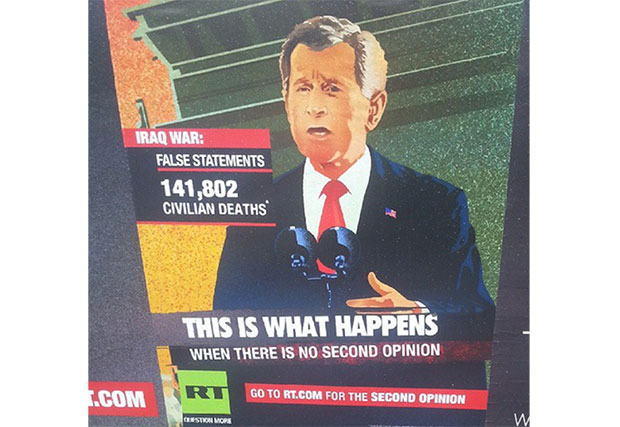

There’s a poster near my house in London. It shows a poorly illustrated George W. Bush, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln early in the Iraq war, with the now infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner behind him. To his side, the tally of dead in the Iraq War (at least according to Iraq Body Count). Underneath is emblazoned the slogan: “This is what happens when there is no second opinion.” It is an advert for Russian propaganda channel RT (formerly Russia Today).

It’s a slightly muddled poster, but the signal is clear: did you feel lied to about the Iraq war? Watch RT.

Curiously, RT, which launched a UK channel on 30 October, seems to believe the poster doesn’t exist. A “report” on the RT website, dated 9 October, claims that the campaign of which this poster is part was “rejected for outdoor displays in London because of their ‘political overtones’”. The story goes on to claim that the “rejected” posters were replaced by ones that simply say “redacted”, before urging readers to download an RT app to view the ads on their phones.

But I have seen the poster. I even took a picture. Yet RT insists it has been banned, saying that outdoor advertising companies cited the Communications Act 2003, which “prohibits political advertising”. This prohibition is indeed to be found in the act, but only applies to broadcast advertisements, not billboard advertisements for broadcasters.

This is a fairly crude illustration of RT’s attitude to the truth. It is simply not an issue. What’s important is something that might sound true, something just about plausible, to suit the agenda (in this case, the agenda is threefold: one, to get people to download the app; two, to sow the belief that “they” are scared of RT; and three, to introduce the notion that political advertising is subject to a blanket ban in the UK).

Fair enough, you might say. But have you seen Fox News? Don’t all sorts of news organisations bend the truth to fit their agenda? There’s a case to be made, but there’s also a crucial difference. RT is funded and controlled by the Kremlin and is on a mission; a mission outlined in a new report by The Interpreter, part of the Institute of Modern Russia (disclosure: Index on Censorship has on occassion crossposted content from The Interpreter).

“The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money” elucidates what we had already long suspected: the Soviet Union may be dead, but Soviet tactics remain. And while the west may not want to believe it is in conflict with Russia, the Russians are already acting like it is (witness reports of heightened Russian air force activity in and near Nato airspace).

The report’s authors, Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev, describe disinformation techniques dating back to the Soviet era: straight propaganda, certainly, but also Dezinformatsiya — the planting of false stories to undermine confidence in western governments. These include alleged coup plots, the bizarre theory that AIDS was created by the CIA, even the suggestion that the assassination of Kennedy was an inside job.

The suggestion is that democracy is a sham, and that democratic governments are at best hypocrites and at worst constantly, deliberately acting against the interests of their own populations.

The best false stories always have a ring of truth and a ring of empathy. Many politicians are hypocrites, some politicians act against the interests of those they should represent. If this much is true, is it that much of a leap to imagine that the entire system is a crock? That democracy and human rights are empty terms? We’re just asking legitimate questions, as every conspiracy theorist ever has said at some point.

Conspiracy theorists find a home at RT. Presenter Abby Martin, for example, who briefly won praise for apparently criticising Russia’s actions in Ukraine, says she still has “many questions” (just asking questions!) about the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, and has used her show to expound on “false flag” attacks, alleged Israeli eugenics, and every US conspiracy theorists’ favourite, the massacre in Waco, Texas of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian cult in 1993.

All this would mean nothing if RT didn’t have a willing audience in the UK, the US and beyond. But a combination of a large budget, photogenic presenters and a certain way with a YouTube clip makes RT a serious player. It never quite veers into the straight out lunacy of Iran’s Press TV, which is quite open about its conspiracist contributors, and it looks like a serious operation. Furthermore, its positioning as an “alternative news source”, albeit one controlled by an increasingly authoritarian, paranoid and erratic Russian state, finds it fans among people who would rail against their own liberal states and societies (on the two occasions I visited the Occupy St Paul’s encampment in London, Russia Today was playing on a large screen there). All the while, the autocratic Putin is strengthened as democracy in undermined worldwide (witness how easily Putin was able to put the kibosh on effective intervention against Syria’s Assad through the relentless repetition of the line that helping the opposition would mean helping jihadist terrorists).

So what, as Lenin himself once asked, is to be done? After reports of UK broadcast regulator Ofcom’s recent investigations into RT for bias earlier this week, some people saw a chance to get RT taken off the air just weeks after it had begun. But this impulse is too close to political censorship in principle, and in practice, an ineffective sanction against a force that has huge power online, with millions upon millions of YouTube hits.

Decent democrats that they are, Weiss and Pomerantsev suggest eternal vigilance is required: we must be able to combat RT’s half truths and insinuations effectively, with hard facts and hard arguments, in order to stop them spreading. As ever, when arguments for counterspeech as the best defence against poison is suggested, one remembers Yeats’s lines: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

But this time 25 years ago, as East and West Germans embraced on top of the Berlin Wall, the world showed that the right argument can win even against the very worst. The Kremlin is playing the same games now as it did in its darkest days. Democrats should be ready to fight back.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Nov 2014 | Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Art and Conflict is the result of a year-long research enquiry, supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, exploring the extraordinary work of contemporary artists, activists and cultural organisations in the context of armed conflict, revolution and post-conflict.

Bringing together a diverse range of perspectives, Art and Conflict aims to raise provocations and open up conversations within the arts, as well as across sectors and disciplines.

An introduction by Michaela Crimmin (Royal College of Art and co-director Culture+Conflict) precedes specially commissioned essays and texts by artist Jananne Al-Ani; Dr Bernadette Buckley (Goldsmiths, University of London); writer Malu Halasa; curator Jemima Montagu (co-director, Culture+Conflict); curator Sarah Rifky (Beirut, Cairo); artist Larissa Sansour; and, Professor Charles Tripp (SOAS). Two further essays by Michaela Crimmin and Dr Bernadette Buckley reflect on art and conflict in Higher Education in the UK.

A free download of the online publication is available here:

Art and Conflict

Art and Conflict

Edited by Michaela Crimmin and Elizabeth Stanton

Design by Tom Merrell

Published by Royal College of Art, London, 2014, with the support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

The Art and Conflict research inquiry was realised as a partnership with Index on Censorship, with additional support from the British Council, Culture+Conflict, the University of Manchester, and Goldsmiths, University of London.

![IMG_0965[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09651-1024x768.jpg)

![IMG_0966[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09661-1024x768.jpg)