24 Sep 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Monday was the beginning of Banned Books Week, the annual celebration of the freedom to read and have access to information. Since the launch of Banned Books Week in 1982, over 11,300 books have been challenged, according to the American Library Association. To mark the occasion, Index on Censorship staff posed with their favourite banned books, and tell why it’s important that they are freely accessible.

David Sewell (Photo by Dave Coscia)

David Sewell – Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“Banned by the Soviet Union for being decadent and despairing and although they’re right in their analysis, the action to ban the book clearly is ludicrous. It’s a Freudian tale of Gregor Samsa who awakes one morning to find he has turned into a human sized bug and how his family react to this turn of events and treat him with revulsion and yes despair, since their main breadwinner is now out of commission. For a book about an insect grubbing about in filth, Kafka’s writing evinces some great beauty as did all his work despite the seam of despair underpinning many of them. Maybe this beauty through despair is what the Soviets meant by ‘decadent’. Kafka was a vital link between the end of the Victorian novel and the literary modernists and the influence of Freud’s ideas increasingly being used in characterisation. That is why ‘Metamorphosis’ is a significant book in the literary canon.”

Aimée Hamilton (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Aimée Hamilton – To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

“Because of its use of profanities, racial slurs and graphically described scenes surrounding sensitive issues like rape, Harper Lee’s award winning novel has been banned in many libraries and schools in the United States over its 54 year history. Having read this beautifully written book at school, I think it should be a freely accessible curriculum staple, to be both enjoyed and admired by all.”

Dave Coscia (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

David Coscia – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

“Failing to or not choosing to see the irony, many schools in the United States banned Fahrenheit 451 based on its offensive language and graphic content. Bradbury’s grim view of a future where firemen are not people who put out fires, but instead set them in an attempt to burn books outlawed by the government, acts as a warning against state sponsored censorship, even if it’s not what he intended. Bradbury himself talks about Fahrenheit as a warning that technology would replace literature and cause humanity to become a “quick reading people.” What resonates with me about the novel is how prophetic that turned out to be. In the age of social media and instant information, humans, myself included, have gotten lazy and spend less time enjoying literature.”

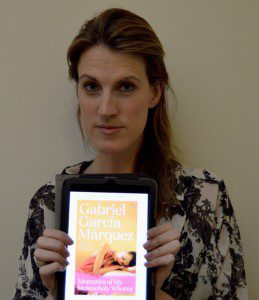

Vicky Baker (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Vicky Baker – Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez:

“I picked this after reading how it was banned in Iran in 2007. Initially, it slipped through the censors’ net, as the Persian title had been changed to Memories of My Melancholy Sweethearts. It was on its way to becoming a bestseller before the ‘mistake’ was realised and it was whipped from shelves, accused of promoting prostitution. It’s classic tale of censors judging a book by its title.”

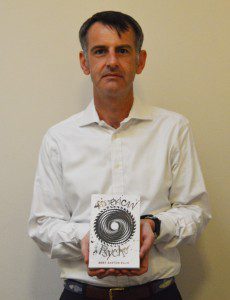

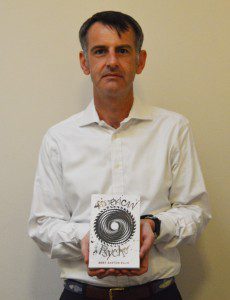

Sean Gallagher (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Sean Gallagher – American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

“No book, no matter how vilified or disliked, should be out of reach for anyone who wants to read it.”

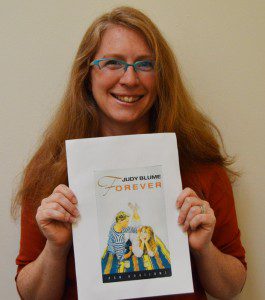

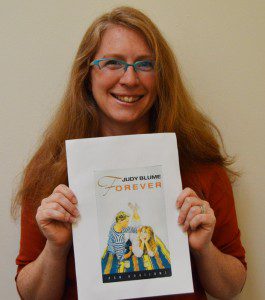

Jodie Ginsberg (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Jodie Ginsberg – Forever by Judy Blume

“I was one of the first girls in my class to own Judy Blume’s Forever and it was passed clandestinely from classmate to classmate until it finally fell apart, dog-eared (and highlighted in certain places…). It is a book that is powerfully linked in my mind – as for so many young kids – to the transition from childhood into the tricky years of teenage life. Reading it felt shocking, even dangerous. But also liberating.”

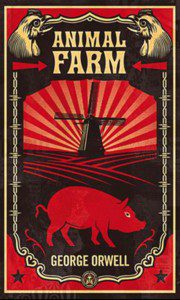

David Heinemann’s choice – Animal Farm

David Heinemann – Animal Farm by George Orwell

“It seems to have upset people from all ends of the political spectrum in one way or another at different times but what I love is that the story is actually quite ambiguous if you read it carefully, tearing pieces out of everyone and all angles. For its extraordinary imaginative power, the sheer audacity of its metaphors and it’s sharp alertness to the truths of life I treasure this book, having read it and been reminded of it so many times. I even adapted and staged the thing once, banning it is like depriving life of liquor.”

Fiona Bradley (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Fiona Bradley – Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“I have chosen Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov because I think it is so deeply disturbing that it deserves to be read. It manages to convey some of the darkest human desires and emotions and these are exactly the kind of things that literature and art should explore. By banning it you are not protecting people but patronising them by refusing their right to judge it for themselves.”

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, News and features

Marilena Katsimi, journalist and general secretary of Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers (ESIEA)

Freedom of information and media’s role as a “watchdog” has deteriorated in Greece over the past six to seven years, as a result of the economic crisis and the fiscal agreements signed by the Greek government.

Marilena Katsimi, journalist and general secretary of Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers (ESIEA) — the largest journalist union in the country — was targeted in October 2012 for commenting on air about the response by Nikos Dendias, ex minister of public order, to an article published in the Guardian. The article mentioned allegations of police brutality against protesters.

Katsimi with her colleague Kostas Arvanitis were suspended for voicing mild criticism, sparking reactions in the journalistic community and on social media.

Index on Censorship spoke with Katsimi about how censorship is exercised in Greece, and to what extent journalists are allowed to report on social struggles in the country.

Index: How would you describe the media censorship in Greece in recent years?

Katsimi: Listen, I want to be clear. There was always censorship in most of mainstream media in Greece (TV, newspapers, radio). It appeared mainly with the form of self-censorship; we all knew for whom we were working for and what we were “supposed” to say or to report.

However, as a reporter for the international news desk of ERT (Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation), the ex state-owned broadcaster, I have experienced a high degree of freedom in reporting. I can’t recall any incident of being targeted at my time there, even when I took a firm stand on certain news reports.

When we were working for the morning news magazine, together with my colleague Kostas Arvanitis, I tried to be fair and balanced according to the journalistic principles a public broadcaster should adhere to: objectivity, plurality etc. In this context, I managed to speak my personal opinion several times without being censored.

However, since the fiscal agreements between the Greek government and the troika and the austerity measures that followed up, we clearly saw that much was about to change.

Initially, the duration of the broadcast was cut by two hours with no convincing explanation. Later on, we were suspended because we commented on the response of Nikos Dendias, ex minister of Public Order, to an article published in the British newspaper The Guardian.

And then came the closure of ERT. In my opinion, it was a move by a suppressive regime that wanted to manipulate public opinion and exclude any opposition voice.

Index: Could you give us some other examples of censorship?

Katsimi: As a general secretary of ESIEA, Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers, I am responsible for the new members that join the Union.

While discussing censorship issues with the 70 new members about to register in ESIEA, I was informed that “censorship pressure was unbearable”. Editors-in-chief, media executives and other managerial staff told journalists in an overt way that “this is the proper way” of reporting while expecting from them “a certain political twist” in stories.

Let me give you another example, the one of privately-owned ANT1 TV. On the eve of the Euro elections in May, the main news bulletin of the station reported unsubstantiated information on opposition party SYRIZA’s alleged internal disagreements about getting out the vote from Golden Dawn (neo-nazi party) sympathisers! At the same time, the bulletin overemphasised that a possible outcome in favour of SYRIZA would destabilise the country and it would be a serious political accident.

After some contacts I made with journalists from privately owned ANT1 TV, I was told that there was a straightforward message on how to “report” the news and “shape” these stories. However, there has not been a single official complaint because many fear of losing their job.

For years, in privately owned media, journalists struggled to express their own voice and criticism through their reports — but now things have gotten much worse.

Index: Can you say something about the conditions in the newspaper sector? It seems that censorship comes always with a great loss of jobs.

Katsimi: Yes, this is true, up to a certain point. From 2005 until 2012 the newspapers’ sales numbers declined by 50% — consequently, there was a great loss of jobs. According to data regarding ESIEA members, the number of unemployed journalists from 2009-2014 is 749 while from 2003-2008 the same number was 69.

Let me say that as a union we do our best so that nobody stays unemployed, however, we have to face this grim reality in the media sector. In consultation with journalists’ assemblies and their representatives we try to push employers to pay on time and pay back compensation that they owe to media workers.

Because of the economic stalemate, there is a huge difficulty for most of the media to take loans from banks and continue to be viable. This in turn, functions as an excuse for media owners to put all sorts of pressure on journalists. They are often being threatened with layoffs in case they refuse a salary reduction; and bear in mind that those still with a job have already seen their salary vanish.

At the moment 400 journalists — members of ESIEA have already contacted our legal department to exercise their right of labor lien. All these cases refer to the three years between 2011-2014.

Index: Let’s get back to content issues. How would you describe media reporting on the major social and political problems in the two years before the EU parliamentary elections in May?

Katsimi: I think that news criteria in Greece vary according to the interests of the particular media outlet. For years, there were hardly any “quality” papers which tried to criticise government policies in an honest and healthy manner. At the same time there were plenty of “tabloids” which reported on the basis of populism and sentimentalism.

However, in my opinion, mainstream media and especially those that supported government policies without doubts or second thoughts, are the ones that did not give space to the social struggles in the form of strikes, anti-fascist rallies, demonstrations and confrontations with the police.

When it came to major news stories like the mining conflict in Skouries, Northern Greece, most of the media failed to report the amount of dissent and the size of the demonstrations that took place in that area and in other big cities. The story of Skouries was by all means a “scoop” of citizen, grass-roots journalism — it rang a “bell” to those who still carried on with a “journalistic consciousness”.

Another example is the Golden Dawn case. Not until international organisations and media outlets shed a light on the role of the neo-nazis, did mainstream media “discover” the phenomenon and attempt to report on it.

I’ d like to add that several social issues like the right to citizenship or human rights abuses against immigrants, asylum seekers and other minorities, were not reported at all or they were downplayed by “right wing” newspapers.

Index: So, what about the future?

Katsimi: After the public broadcaster’s shutdown and the launch of the new state-run broadcaster NERIT, all I see is that the government succeeded in suppressing alternative opinions and controlling, more than ever, public broadcasting.

On the other hand, there is still hope in citizen journalism and in new media collectives that are not bound to big economic interests and are free to report on social issues mainstream media neglect.

This article was published on Wednesday, 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Sep 2014 | Events

Author: Minnesota Historical Society

**UPDATE 02/10/14: Index will be joined by the Schools Officer Pc for Southwark to discuss the police’s role in freedom of expression.**

The police play an important part in civil society but how far should they go in protecting free speech?

The recent protests in Ferguson have received international attention as police and protesters continue to clash, but are the police just doing their job and keeping the peace? This situation has been replicated all over the world as police and public battle over civil liberties both in the streets and online, but we want to know – what do you think?

For this month’s Draw the Line event, Index on Censorship wants to know if you think the police should do more to protect our right to free speech?

Join Index on Censorship and industry professionals as we debate, discuss and explore what role do you think the police should play in protecting our right to free speech and where do you draw the line?

WHEN: Thursday 9th October, 6pm

WHERE: Index on Censorship, 92-94 Tooley St, London, SE1 2TH

TICKETS: This event is FREE for under 25s but please RSVP here.

If you need any more information please contact Fiona Bradley on [email protected]

22 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Statements

The European Commission (EC) on Thursday released a “mythbuster” on the controversial Court of Justice of the European Union ruling on the “right to be forgotten”. The document tackles six perceived myths surrounding the decision by the court in May to force all search engines to delink material at the request of internet users — that is, to allow individuals to ask the likes of Google and Yahoo to remove certain links from search results of their names. Many — including Index on Censorship — are worried about the implications of the right to be forgotten on free expression and internet freedom, which is what the EC are trying to address with this document. But after going through the points raised, it is clear they need some of their own mythbusting.

1) Groups like Index on Censorship have not suggested “the judgement does nothing for citizens”. We believe personal privacy on the internet does need greater safeguards. But this poor ruling is a blunt, unaccountable instrument to tackle what could be legitimate grievances about content posted online. As Index stated in May, “the court’s ruling fails to offer sufficient checks and balances to ensure that a desire to alter search requests so that they reflect a more ‘accurate’ profile does not simply become a mechanism for censorship and whitewashing of history.” So while the judgement does indeed do something for some citizens, the fact that it leaves the decisions in the hands of search engines – with no clear or standardised guidance about what content to remove – means this measure fails to protect all citizens.

2) The problem is not that content will be deleted, but that content — none of it deemed so unlawful or inaccurate that it should be taken down altogether — will be much harder, and in come cases, almost impossible to find. As the OSCE Representative on Media Freedom has said: “If excessive burdens and restrictions are imposed on intermediaries and content providers the risk of soft or self-censorship immediately appears. Undue restrictions on media and journalistic activities are unacceptable regardless of distribution platforms and technologies.”

3) The EC claims the right to be forgotten “will always need to be balanced against *other* fundamental rights” — despite the fact that as late as 2013, the EU advocate general found that there was no right to be forgotten. The mythbuster document also states that search engines must make decisions on a “case-by-case basis”, and that the judgement does not give an “all clear” to remove search results. The ruling, however, is simply inadequate in addressing these points. Search engines have not been given any guidelines on delinking, and are making the rules up as they go along. Search engines, currently unaccountable to the wider public, are given the power to decide whether something is in the public interest. Not to mention the fact that the EC is also suggesting that sites, including national news outlets, should not be told when one of their articles or pages have been delinked. The ruling pits privacy against free expression, and the former is trumping the latter.

4) By declaring that the right to be forgotten does not allow governments to decide what can and cannot be online, the mythbuster implies that governments are the only ones who engage in censorship. This is not the case — individuals, companies (including internet companies), civil society and more can all act as censors. And while the EC claims that search engines will work under national data protection authorities, these groups have yet to provide guidelines to Google and others. The mythbuster itself states that a group of independent European data protection agencies will “soon provide a comprehensive set of guidelines” — the operative word being “soon”. This group — known as the Article 29 Working Party — is the one suggesting you should not be informed when your page has been delinked. And while it may be true that “national courts have the final say” when someone appeals a decision by a search engine to *decline* a right to be forgotten request, this is not necessarily the case the other way around. How can you appeal something you don’t know has taken place? And what would be the mechanism for you to appeal?

As of 1 Sept, Google alone has received 120,000 requests that affect 457,000 internet addresses and may remove the information without guidance, at their own discretion and with very little accountability. To argue that this situation doesn’t allow for at least some possibility of censorship, seems like a naive position to take.

5) All decisions about internet governance will to an extent have an impact on how the internet works, so it is important that we get those decisions right. In its current form, the right to be forgotten is not up to the job of protecting internet freedom, free expression and access to information.

6) It may not render data protection reform redundant, but we certainly hope the reform takes into account concerns raised by free expression groups on the implementation of, and guidelines surrounding, the right to be forgotten ruling.

This article was posted on 22 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org