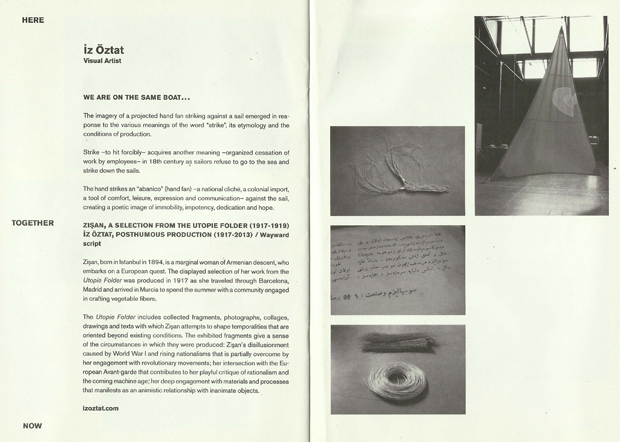

International exhibition censored by Turkish Embassy in Madrid

Last year, the exhibition Here Together Now was held at Matadero Madrid, Spain. Curated by Manuela Villa, it was realised with the support of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, Turkish Airlines and ARCOmadrid. But in the exhibition booklet, the explanatory notes to artist İz Öztat’s work “A Selection from the Utopie Folder (Zişan, 1917-1919)” was censored upon the request of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, and the expressions “Armenian genocide” and the date “1915” were taken out.The case shows how the Turkish state delimits artistic expression in the projects it supports, and how it silences the institutions it cooperates with.

After Turkey was chosen as the country of focus for the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid International Contemporary Art Fair, the designated curator Vasıf Kortun and assistant curator Lara Fresko started to work with the galleries that would join the fair. They helped in fostering connections between the Madrid arts institutions and artists in Turkey; as well as with the embassy officers in charge of the financial support of events such as Here Together Now, which would run as a parallel event to the main fair. The embassy indicated that it would support this exhibition with the generous sum of €250,000. However, it did not provide any written documentation guaranteeing this support, and outlining the mutual duties and responsibilities of the parties involved. Likewise, during the realisation of the project, there was no written communication between the embassy and Matadero Madrid, and all negotiations took place verbally, over the phone. It was in this manner that, from the very beginning, the state kept the exact conditions of its support ambiguous and created a tense situation for the organisers. Ultimately, this working practice gave the Embassy the possibility of denying the promised support, in the event that their request was not carried out.

This is not the first case of the Turkish state censoring an arts event it sponsors abroad. We frequently hear about such cases off the record, and at times through the media. One of the best-known cases of state intervention took place in Switzerland, during the 2007 Culturespaces Festival. Director Hüseyin Karabey’s film Gitmek – My Marlon and Brando, which had received support from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, was taken out of the festival program at the very last minute, at the request of an officer from the General Directorate of Promotion Fund, on the pretext that “a Turkish girl cannot fall in love with a Kurdish boy” as was the case in the film. The officer threatened the festival organisers with withdrawal of sponsorship totaling €400,000 — much like the case of the Madrid exhibition. The festival director decided that they could not go ahead with the event without this support, ceded to the censorship request, and accepted to take the film out of the program. However, independent movie theaters in Switzerland criticised this decision and ended up screening the film independently of the festival.

Both examples show that the state controls the content of the projects it sponsors abroad, interferes with the organisations on arbitrary grounds, and violates artists’ rights by threatening the very institutions it collaborates with.

The administrative channel for the state’s support to events outside of Turkey is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Promotion Fund Committee, established under law 3230 (10 June, 1985) with the aim of supporting activities that “promote Turkey’s history, language, culture and arts, touristic values and natural riches”. The Committee reports directly to the Prime Minister’s office, and is presided over either by the Prime Minister himself, the Vice Prime Minister or a minister designated by the PM. It has five more members: Deputy Undersecretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the general managers of the Directorate General of Press and Information, and the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). The objective of the fund is “to provide financial support to agencies set up to promote various aspects of Turkey domestically and overseas, to disseminate Turkish cultural heritage, to influence the international public opinion in the direction of our national interests, to support efforts of public diplomacy, and to render the state archive service more effective”.

The Committee convenes at least four times a year upon the invitation of its president to evaluate project applications. The only criterion in accepting a project is whether it complies with the objectives mentioned above. After the Committee carries out its evaluation, the projects are put into practice upon the approval of the PM. Representative offices of the Promotion Fund Committee monitor whether the projects are implemented in compliance with the principles of the fund. In the case of the Madrid exhibition, the Turkish Embassy assumed the role of representative office. In this respect, as per the relevant regulation, the embassy was in charge of controlling the project, signing protocols with project managers to outline mutual duties and responsibilities, making the necessary payments, and delivering the project report to the Committee. As such, the embassy’s avoidance of all written documentation is in breach of the principles and modus operandi established by its own regulations.

Overall, it can be said that the Promotion Fund Committee does not meet the criteria of transparency and accountability generally expected from a public agency. The dates when the committee convenes to evaluate the projects are not announced, and the committee members, annual budget, sponsorship priorities and selection criteria are not made public. The sums paid to projects sponsored and the content of the projects are not disclosed officially. In other words, there is no transparency about the distribution of the funds, or about the auditing procedures. Such structural problems make it even harder to reveal and question the state’s violation of the right to artistic expression.

Another important aspect of this case is that the state constantly tries to reproduce its dominant discourse based on the denial of past and ongoing human rights violations such as forced displacement, genocide, political murders, burning of villages, enforced disappearances, rape, and torture through security forces; and does its utmost to silence any expression which contests this discourse. The centenary of the Armenian genocide, 2015, is drawing near. As such, it becomes even more important to demand that the Turkish state be held accountable for this human rights violation.

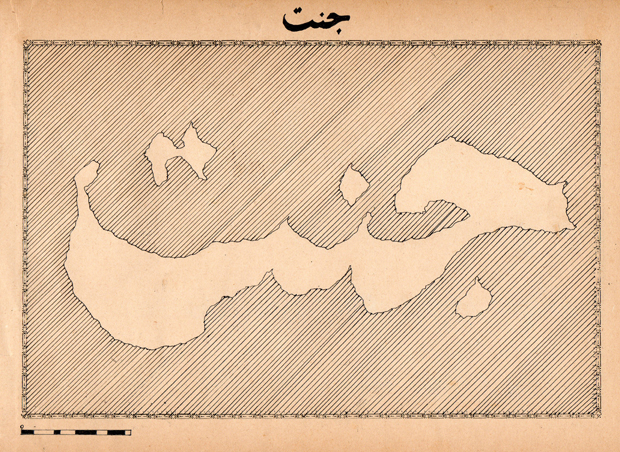

Map of Cennet/Cinnet (Paradise/Possessed Island). Zişan, 1915-1917. Ink on paper, 20×27 cm. Dedicated to the Public Domain

Siyah Bant is a research platform that documents and reports on cases of censorship in arts across Turkey, and shares these with the local and international public. In the context of this work, we wanted to investigate the censorship that occurred at Here Together Now. In accordance with the Right to Information Act, we asked the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to explain the legal basis of the censorship they imposed on the booklet. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicated that Matadero Madrid and curator Manuela Villa were the only authorities in charge of selecting the artists who would participate in the workshops of ARCOmadrid, designating the content of the works to be produced during the workshops, and preparing all printed matter in connection to the event. We were unable to obtain an official statement from curator Manuela Villa, despite several inquiries. Finally, we conducted an interview the artist İz Öztat to understand how the censorship took place, and how she experienced the process.

How did you come to be involved in the exhibition?

I was invited by Manuela Villa, curator of Matadero Madrid, after meeting her in Istanbul. Matadero planned for a residency program and an exhibition project titled Here Together Now to take place concurrently with the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid Art Fair that had a section consisting of invited galleries from Turkey. By the time I signed the contract with Matadero Madrid, I knew that the project was partially supported by the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and Turkish Airlines.

Here Together Now was a process that allocated the resources with an emphasis on living and working together. Cristina Anglada (writer), Theo Firmo, Sibel Horada, HUSOS (a collective of architects), Pedagogias Invisibles (art mediation collective), Diego del Pozo Barrius, Dilek Winchester and I had six weeks together, during which we figured out common concerns, negotiated our relationship to the institution’s public, designed the working and exhibition space, collaborated and produced our works.

Can you tell us about the nature of contract with the institution and if there were any limitations indicated as to the nature of your work?

We signed a very detailed contract with Matadero Madrid that laid out the responsibilities of the institution and the artist in relation to the production and authorship of new work but there were no limitations outlined in the contract. I took it for granted that the artist has freedom of expression and institutions do not interfere in the produced content.

The institution was extremely supportive of the project. They were engaged in our discussions and ready to help once we started producing the work.

Could you talk a bit about the work that you prepared for Matadero Madrid?

The work shown in the Here Together Now exhibition was part of an ongoing process, in which I imagine ways to conjure a suppressed past. Since 2010, I have been engaged in an untimely collaboration with Zişan (1894-1970), who is a recently discovered historical figure, a channeled spirit and an alter ego. By inventing an anarchic lineage with a marginalized Ottoman woman, I try to recognize a haunting past and rework it to be able to imagine otherwise. For the exhibition at Matadero Madrid, I produced and exhibited “A Selection from Zişan’s Utopie Folder (1917-1919)” accompanied by works from the “Posthumous Production Series”, in which I depart from Zişan’s work to open a path towards the future in our collaboration. The exhibited work was complemented by a publication with three interviews, which situates the work and builds a discourse around it.

Which aspect of the work was censored? How did the process of censorship occur, and what kind of dilemmas did you face in this process?

Manuela Villa, the curator, met with me in the exhibition space one evening a few days prior to the opening. Officials from the Turkish Embassy had threatened to withdraw their financial support, if the demanded changes were not made. I had to make a decision on the spot and accepted the censorship in the booklet, but not in the publication complementing the work. The exhibition booklet was reprinted and the sentence was changed to “Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894, is a marginal woman of Armenian descent, who embarks on a European quest.”

As I said before, there was an emphasis on the community we built together during the residency at Matadero and I didn’t want to make a decision alone that would put the whole project at risk. Because of the time constraints, we were only able to meet with the other artists after the opening to discuss the precarious condition that we were all in. The institution didn’t have any signed documents from the Embassy committing to the sponsorship. Everything was communicated verbally and there was no written documentation. I was not able to reach out for a support network to resist the situation, not least due to the immediacy the decision required.

The exhibition booklet that was presented to the embassy was altered but the publication accompanying your work remained unchanged. How did the curator and other artists react to your refusal to change the publication?

I could not stand my ground with regard the exhibition booklet because it concerned everybody in the project. Yet, I was able to take full responsibility of my own work. We were informed that officials from the embassy will visit the show prior to the opening and I was ready to withdraw the work, if there was any interference. Everybody was supportive of my decision.

What happened on the day of the opening? Did you feel the need to prepare yourself?

In the end, none of the officials from the embassy came to the opening or the exhibition. There was no confrontation regarding the work. There might be a few reasons for this that I can think of. Maybe, they felt entitled to interfere with the content of the exhibition booklet because it had the logo of the embassy and could dismiss my publication since it only had the logo of Matadero Madrid. It was not of benefit for the embassy to confront me in a situation that would have made the case public.

As Siyah Bant we inquired both with the curator and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in order to understand how this censoring motion played out. Given that the ministry rejects any responsibility and instead assigns all responsibility to the curator, and that the curator was acting under the duress of loosing all funding last minute, where does this leave you as the artist? How do you make sense of what happened to your work?

Since I accepted the censorship, my only option was making the situation public after the fact. I have been working in cooperation with Siyah Bant since I got back from Madrid. It took a few months to receive an official response from the embassy, which denied all responsibility. We wanted to make the case public after receiving a statement from the curator or the institution. I was unable to receive such a statement, and Siyah Bant is working on that now.

I see it as an experience, in which I was able to test and see the boundaries of government support that is allocated to arts and culture for promoting the country. If you decide to accept this support and challenge official policies, a system of censorship starts to operate.

Next year marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide which will inevitably bring about numerous artistic and cultural reflections on the subject. Given the current climate in Turkey, how confident are you that artistic freedom of expression will be respected?

We are going through a period, in which it is impossible to make predictions about what can happen even the next day. I can only hope that genocide denial at state level comes to an end. I am sure that artists will articulate their own ways of recognising the Armenian Genocide and confronting its denial. You are probably more prepared than I am to predict and know what kinds of mechanisms are at work to limit the production and dissemination of such work.

What would be your recommendations to other artists taking part in cultural events that are supported by the Turkish government?

Based on my experience, I think that artists and art institutions need to act in solidarity in these situations. If there is funding from the Turkish state, the institutions and artists involved need to be aware that the state monitors the content. The various institutions that distribute state funding do not provide written documents about their commitments and communicate their demands mostly in person or by phone. Demanding written documentation at every step is necessary. Artists who are considering to take parts in projects that receive state funding, can demand from the art institutions to be more transparent about the budget and its workings so that they can be prepared to make alternative plans if the state funding does not come through as promised.

If I encountered the same case of censorship now, I would not feel obliged to make a decision immediately and in isolation. I would consult the rest of the group and demand the involvement of the institution.

This article was posted on May 28 2014 at indexoncensorship.org