15 May 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Nick Griffin, leader of the British National Party, arrives at a protest in June 2013 in Westminster. (Photo: Paul Smyth / Demotix)

BBC Radio Five Live’s Breakfast yesterday dutifully carried out its public service remit by interviewing Nick Griffin, the world’s most tedious Nazi demagogue, ahead of the European elections. Griffin’s British National Party does have some seats in the European Parliament, so is entitled to some airtime.

It was a dull interview. They always are. The BBC interviewers–in this case, Nicky Campbell–want to pick away at the BNP facade, but always somehow miss out on the really strange stuff. Long ago, I vowed that I would never write about Griffin without pointing out that he had written a pamphlet called “Who Are The Mindbenders?”, which is a catalogue of Jewish and Jewish people who work in the media. Griffin believes that these evil Jews (sorry, “Zionists”) are involved in an enormous plot to keep him–the saviour of the white race–out of the press and off the airwaves.

The conspiracist aspect of BNP policies is often overlooked, with the straightforward racism critiqued more heavily. So it was here. Campbell asked Griffin if he had a problem with black and mixed-race players representing England in the upcoming World Cup. Griffin, barely missing a beat, started complaining about BBC liberals smearing him and worse, denying him airtime.

“The BBC owes me 12 Question Times,” he declared, bemoaning his lack of invitations to appear on the BBC’s Thursday night festival of shouting from and at the telly.

It might have been interesting to delve into why Griffin felt he was being kept off Question Time, to see how long he would be able to maintain a line before going full Doctor Strangelove. As it was, we got only the superficial whine. The whine of the martyr-bully.

It is the background sound of our time. There is absolutely no one engaged in modern public life at any level at all who has not complained that they’ve been silenced, denied a platform, bullied into submission by a cruel cabal of agents of reaction or “the liberal agenda”, take your pick.

That is not to say people are not censored, even in the lovely modern 21st Century. It happens, quite a bit. People get locked up for saying stupid things on the internet that affront public sentiment. For years the libel laws restrained reporters, reviewers and the man on the Clapham Omnibus from saying what they really knew, or thought, or thought they knew. And no reader of this site needs to be told what happens in the less than democratic countries all over the world.

But there is actual censorship, and there is the claim to being censored, which are often two separate things. The BNP’s Griffin, UKIP’s Nigel Farage, and every Blimp all the way to Westminster delights in telling us, at length, the things that nobody, least of all them, is allowed to talk about anymore.

Meanwhile, on the left and the pseudo-left, there is an obsession with “platforms”; who has one, who deserves one, who is denied one. Editors and writers who do their best to represent as many diverse views as possible are denounced routinely for the articles they haven’t published rather than the ones they have. Every oversight is evidence of a conspiracy rather than a cock-up. The right people are always being excluded by the wrong people. If only, if only everyone shut up and let me speak, we think, then I could sort everything out.

It’s ironic that many of those who argue most vehemently that they are being censored are the exact ones who demand everyone else shut up. Intersectional feminists who insist they are being excluded from debate demand that radical feminists be “no platformed”. Ukipers who claim they’re not allowed talk about immigration want the police to arrest their opponents in anti-racist movements. All of them, simultaneously, noisily, will end up invoking Niermoller’s “First they came for…” (with the possible exception of the BNP, who, stopping short of displaying sympathy with Communists or Jews, instead content themselves with calling their opponents “the real fascists”, as I once heard Griffin do at Oxford Union).

Why is this? Why does everyone want to be censored?

It’s possible that the simple reason is that we are constantly improving as a society. Triumphalism and privilege are pretty much taboo for many. On the face of it, most of the people reading this, and certainly the person writing it, are probably the luckiest sons of bitches to ever have walked the earth. But a combination of our still-relevant horror at the great wars of the last century, plus a greater ability to learn about the ideas and experiences of others, make most of us wary of revelling in our role as the victor. Instead, we prefer to be the underdog, because underdogs are more virtuous–victims rather than perpetrators. Martyrs, even.

The Nazis and Communists of the 20th century also believed they were more sinned against than sinning, but the difference was that they were certain they would show the world who was really boss. Now, no one outside the most extreme movements – Al Qaeda; or North Korean Juche – really wants to state that aim openly. We want to remain oppressed. Censorship is considered almost universally as a bad thing, so people on whom it is inflicted are good.

The background whine of censorship, emanating even from the powerful may just be the tiny price we pay for a world that is generally better and kinder.

I think we can live with that.

This article was posted on May 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 May 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Turkey

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

Last Thursday, after nearly eight years of detention three journalists were among a group released from a prison near Istanbul. The journalists Füsün Erdoğan, Bayram Namaz and Arif Çelebi were arrested in 2006 and accused of belonging to the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP), which is considered a terrorist organization in Turkey. For journalists and activists who had been closely following the case, the sudden release came as a surprise after months of resistance from local courts.

In November 2013, seven years after her arrest, Erdoğan was sentenced to life in prison for her alleged involvement with the MLKP. She has denied involvement with the group. In a letter Erdoğan wrote that was published by the CPJ last year, she explicitly rejected the charges: “In reality, there was only one real reason for our arrest: police were trying to intimidate members of the progressive, independent, democratic, and alternative media.” Erdoğan is a founder of the leftist radio station Özgür Radyo and began writing for the independent news website Bianet while in prison, mailing editors her regular dispatches, says Elif Akgül, Bianet’s freedom of speech editor.

Earlier this year, judicial reforms in Turkey brought down the maximum legal detention time for prisoners awaiting sentencing in terrorism cases from ten years to five. While Erdoğan had been sentenced in local court, she is still awaiting a verdict from an appeals judge. Following the new reform, Erdoğan’s lawyers applied for her release from prison, but the request was denied in March. Around the same time, eight journalists were released who had been detained in 2011 and were accused of belonging to the Kurdish KCK union, which is also considered a terrorist organisation in Turkey.

The turnarounds over the past months, from Erdoğan’s life prison sentence last year to her release from prison a few days ago, have exposed the Turkish judicial system’s capacity for dragging on a case in uncertainty. Erdoğan was not informed of the charges against her until two years into her detention, and served nearly eight years without receiving a final verdict. Now, after Erdoğan’s sudden and unexpected release from prison, the court’s decision also shows the opacity of court regulations in Turkey. The implications of a broken judicial system for press freedom are troubling—especially in a country with consistently high numbers of jailed journalists.

Füsün Erdoğan’s case has attracted the attention of advocacy organizations like the Turkish Journalists’ Union, the European Federation of Journalists, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters without Borders. Because she’s a Turkish-Dutch dual citizen, last year the Dutch Association of Journalists (NVJ) also began campaigning for her release.

Thomas Bruning is general secretary of the NVJ and has started campaigns in the Netherlands to bring attention to Erdoğan’s case. What drew the most reactions, he says, was when the NVJ had 10,000 posters made featuring a picture of Erdoğan with the text “Füsün Erdoğan must be free” and “journalists are not terrorists” in Dutch. The association sent the posters out to subscribers of their magazine and asked them to share pictures of the posters on social media. Over the last few months, Bruning and the NVJ have also been in contact with Erdoğan’s son, and Bruning gave a speech outside the Dutch parliament when Erdoğan’s son went on a hunger strike there to draw attention to his mother’s case. Now that Erdoğan is out of prison, the NVJ is focused on having the charges against her dropped. “We always said that there are two problems left – one is that, although in the last few months journalists have been released, there are still a lot of journalists in prison in Turkey. The second is that Füsün is released but the charges haven’t been dropped yet. She’s not free to travel and she’s awaiting the appeal. She’s not a free citizen,” Bruning said.

Füsün Erdoğan’s surprise release from prison is not an indicator of lasting change in Turkey’s press freedom situation. During its 2013 prison census, the CPJ reported that 40 journalists were in Turkish prisons. Yesterday, five more journalists were released from prison who had been held in connection to the KCK case. Despite the release of multiple journalists this year, the CPJ estimates that at least 11 journalists are still imprisoned in Turkey.

At protests in Istanbul on May 1, journalists were detained and Bianet reported that at least 12 were injured. A few weeks ago, the journalist Önder Aytaç was sentenced to ten years in prison for a 2012 tweet that insulted Prime Minister Erdoğan. Akgül says freedom of speech is evolving but not improving in Turkey. “In the 1990s, you were killed for being a journalist, in the 2000s you were arrested for being a journalist. Right now, you become unemployed if you’re a journalist,” she said.

Erdoğan’s legal situation remains precarious as she awaits appeal trial, but while Akgül says her release is a positive development, the case is a warning sign for the media climate in Turkey. “It’s a threat not just for the journalists who are on trial, it’s a threat for the others too,” said Akgül. “Because a journalist now working in Turkey, writing critical stuff, knows they can be jailed for being a terrorist member, administrator, member, they can be jailed for lifetimes.”

This article was posted on 15 May 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 May 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News

(Image: Håkan Dahlström)

A new set of guidelines laid out by the EU, and contributed to by Index on Censorship, will specifically look at freedom of expression both online and offline, and includes clauses, among others, on whistleblowers, citizens’ privacy and the promotion of laws that protect freedoms of expression.

According to the Council of the European Union press statement, freedom of opinion should apply to all persons equally, regardless of who they are and where they live, affirming this freedom “must be respected and protected equally online as well as offline”.

Significant consideration within the EU Human Rights Guidelines on Freedom of Expression Online and Offline, adopted on 12 May, is paid to whistleblowers with the council vowing to support any legislation adopted which provides protection for those who expose the misconduct of others, as well as reforming legal protections for journalists’ rights to not have to disclose their sources.

Reinforcing this, the new guidelines enable the Council to help those, journalists or others, who are arrested or imprisoned for expressing their opinions both online and offline, seeking for their immediate release and observing any subsequent trials.

Member states also have an obligation to protect their citizens’ right to privacy. In accordance with article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the guidelines claim “no one should be subject to arbitrary or unlawful interference with their privacy“, with legal systems providing “adequate and effective guarantees” on the right to privacy.

The guidelines will provide guidance on the prevention of violations to freedom of opinion and expression and how officials and staff should react when these violations occur. The guidelines also outline the “strictly prescribed circumstances” that freedom of expressions may be limited; for example, operators may implement internet restrictions (blockages etc.) to conform with law enforcement provisions on child abuse. Laws under the new guidelines that do adequately and effectively guarantee the freedom of opinions to all, not just journalists and the media, must be properly enforced.

“Free, diverse and independent media are essential in any society to promote and protect freedom of opinion and expression and other human rights,” according to the Council press release. “By facilitating the free flow of information and ideas on matters of general interest, and by ensuring transparency and accountability, independent media constitute one of the cornerstones of a democratic society. Without freedom of expression and freedom of the media, an informed, active and engaged citizenry is impossible.”

Read the full set of guidelines here.

This article was posted on May 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 May 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Digital Freedom, European Union

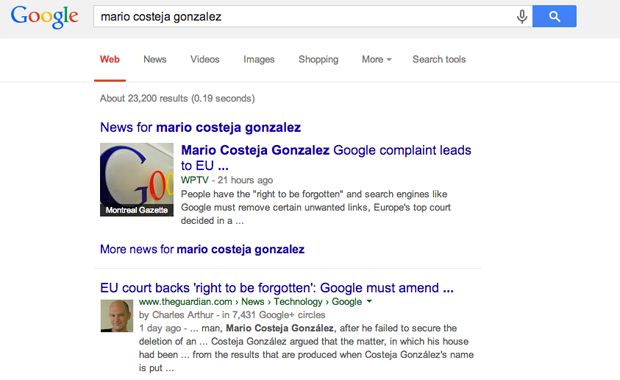

Tuesday’s ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) said that internet search engine operators must remove links to articles found to be outdated or irrelevant at the request of individuals.

No legal oversight, no legal framework, no checks and balances

Although it was made with intention of protecting European citizens’ personal data, the court’s ruling opens the door for anyone to request that anything be hidden from a search engine database with no legal oversight. The ruling could have negative implications to freedom of expression in the EU.

The case dates back to March 2012, when a Spanish citizen, Mario Costeja González, filed a complaint against Google and the newspaper La Vanguardia after discovering that a Google search for his name produced results referring to his homes repossession and auction for non-payment of social security contributions in 1998.

González argued that the 1998 auction notice mentioned in La Vanguardia should no longer be linked to his name in internet searches.

The information on La Vanguardia site had been published legally and was protected by the right to information. However, relying upon the EU’s data protection directive — which the CJEU last year argued did not establish a right to be forgotten, the judges ruled that González’s privacy rights override not only the economic interest of Google as a search engine, but also “the interest of the general public in having access to that information upon a search relating to [González’s] name.” As a result they ordered all links to the auction notice be removed from Googles search results.

The ruling now makes it possible for individuals to request an internet search engine operator to remove links to content found outdated or irrelevant following a search made on the basis of a person’s name. The request can be about any item, included lawful pages, containing true information, that are publicly available. While it’s understandable that people might want to restrict access to private information (embarrassing pictures, for example), Index does not believe that the ruling addresses this in an appropriate way.

A search engine is not a publisher and it neither owns nor stores the web pages containing information relating to a person, especially when this information emanates from public records. The courts ruling sets different standards between search engines, which are intermediaries, and publishers, who produce the content and are responsible for making the information public. In this particular case, it will mean there is a difference between searching what is publicly available in the newspaper archives in a local library and what is publicly available on the internet.

Privatisation of censorship: allowing search engines to become censor-in-chief

The US magazine The Atlantic notes the court ruling explicitly mentions González’s auction notice. So would that mean the ruling itself could be made unsearchable online if Gonzalez requested it? It would be up to Google and others discretion to decide whether or not the public’s right to access the court decision overrides González’s privacy.

The ruling specifies that a fair balance should be sought between the public’s right to access given information and the data subjects right to privacy and data protection, but one of our greatest concerns is that it does not provide any legal framework for the search engine operator to implement the removal, nor does it provide sufficient elements to guarantee public interest defence against removal. It leaves to private companies the power to amend search results without any legal oversight and checks and balances.

The ruling makes a search engine operator a controller able to rectify, erase or block links to information publicly available. According to the judges, the controller must take every reasonable step to ensure that data which do not meet the requirements of that provision are erased or rectified. It means that private companies such as Google or Yahoo would be in a position to decide whether or not information is “adequate, relevant” and “kept up to date”. There is a provision in the ruling for public interest to be taken into account but, again, this is not something that search engines should be deciding. Furthermore, the ruling does not provide for what happens when irrelevant information is hidden from public view and then becomes suddenly relevant because a former nobody suddenly becomes, say, a public figure.

Alongside practical implications for companies that would be required to implement the ruling, search engine operators should not be responsible for taking such decisions. Should they choose to refer decisions to local information commissioners, the commissioners could find themselves deluged with requests they simply do not have the resources to manage. Britain’s Information Commissioner has already described the regime as one no one will pay for.

A bad precedent for countries within and outside Europe

Although the ruling was welcomed by some as a clear victory for the protection of personal data of Europeans; it clearly restricts EU citizens right to information freely available on the internet. The ruling as it stands could be used to censor legitimate content and takes Europe closer to countries that have a tradition of internet control. At a time when the number of takedown requests is increasing globally, and more countries are banning Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, Index fears this ruling could further empower those who try to silence information available on the web and rein in online freedom of expression.

Journalists who live in countries where they experience censorship everyday understand this instantly; this is about removing information at whim from the public domain or at least making it much harder to find. Making it more difficult for journalists to undercover stories about fraud, child abuse and expenses scandals. And just because an individual would rather that information could not be found.

In Turkey for example, the government blocked the country’s access to YouTube in March, after banning Twitter earlier in the month, in an effort to quell anti-government sentiment prior to local elections. The government officially banned Twitter after the network refused to take down an account accusing a former minister of corruption. In the Turkish case, there is the risk that material objectionable to the government would be more easily removed by deleting the links to relevant articles and blog posts.

“This is worrying news because the right to be forgotten can quickly morph into the right to polish ones public image, using privacy rights as an excuse. The public also has rights, and access to public information about citizens is one of those,” says Turkish journalist Kaya Genc. “In the age of social media, it is very difficult to tell who is a public figure our lives are all public now and the sooner we accept this, the better.”

In the end, the ruling leaves more questions than it answers: Who decides what’s “relevant”? Which person gets to hide access to which information? What stories will be made to “disappear”? When does a story become out of date? Could US citizens search for information about EU citizens on search engines that EU citizens would not be able to see?

And how long before this article is inaccessible because someone mentioned in it wants to hide it from public view?

This article was posted on May 14, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org