12 Oct 2015 | mobile, News and features, United States

|

Battle of Ideas 2015

A weekend of thought-provoking public debate taking place on 17 & 18 October at the Barbican Centre. Join the main debates or satellite events.

The Birth of a Nation: more than racism on film?

What we do we make of the film today? Does the current reaction to it mirror contemporary controversies about free speech and the arts? Dr Graham Barnfield, Jenny Barrett, Nadia Denton, Kunle Olulode and Dr Melvyn Stokes with chair Nathalie Rothschild. Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 2-3:30pm

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details

After Ferguson: policing and race in America

Kunle Olulode will also be part of a panel chaired by Jean Smith with Dr James Campbell, Dr Anna Hartnell, Dr Kevin Yuill at Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 10-11:30am

Where: Pit Theatre, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details

Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?

Join Manick Govinda, Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg, Cressida Brown, Nadia Latif, Nikola Matisic with chair Claire Fox at the Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 4-5:15pm

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details |

“Why censor the motion picture — the labouring man’s university? Fortunes are spent every year in our country teaching the truths of history, that we may learn from the mistakes of the past a better way for the present and future. The truths of history today are restricted to the limited few attending our colleges and universities; the motion picture can carry these truths to the entire world, without cost, while at the same time bringing diversion to the masses. As tolerance would then be compelled to give way before knowledge and the deadly monotomy of the cheerless existence of millions would be brightened by this new art, two of the chief causes making war possible would be removed.”

So wrote DW Griffiths in 1916 in the aftermath of his epic film Birth of a Nation. Fine words, loaded with twisted assumptions that rankle, irritate and anger anti-racists even a century on.

Birth of a Nation is no ordinary film. Inspired by Reverend Thomas Dixon’s novel and play The Clansman, it was engulfed in controversy: its central theme championed the post-civil war reformation of the Klu Klux Klan and blatantly suggested that American society only functioned effectively through the subjection of its black population. Worse still, its depiction of the defeated white slave-owning class as honourable victims of corrupt northern unionists and ‘carpet baggers’ contrasted against newly-liberated former slaves as feral, lustful, illiterates drunk with power and indulging in legally-sanctioned excess and wanton violence mainly to force white women into sexual relations.

Not surprisingly, on its release it was attacked by black journalists, political campaigners, trade unions, local government and filmmakers. The then newly-formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People lead a national campaign against it. In total, the film was banned in five states and 19 cities. Even as late as 1946, the Museum of Modern Art in New York refused to screen it.

Protests and audience reaction to the film, for and against, led to violent and, in some cases, fatal clashes. This continued right up to the 1950s when rumours of a talking re-make of the film swept Hollywood, reactivating the muted echo of labour union protests from earlier years.

In the 1980s, film historian Donald Bogle put forward the theses that film effectively shaped the images of black characters in Hollywood by consolidating five stereotypes: the Uncle Tom, the Comical Coon, the Tragic Mulatto, the Sexless Mammy and the over-sexed and violent Big Buck. These are ideas that would later be taken up by Robert Townsend in his comedic Hollywood Shuffle and more recently in Spike Lee’s polemic Bamboozled.

Nevertheless, Birth of a Nation was both a commercial and artistic success. Superbly directed by Griffiths, it altered the entire course of filmmaking, utilising innovative filming techniques such as close-ups, track shots and cross-cutting action sequences. The film initially made the relatively huge sum of $100,000 and earned over $18 million by 1931. It was only superseded by Gone With the Wind, another slavery epic that took its cue directly from Griffiths’ work. By the time of World War II, it had been seen by over 200 million people worldwide.

But that still doesn’t fully explain why the scope of Griffith’s work continues to trouble critics, filmmakers and fans alike. One of the best responses to this dilemma came from Richard Brody when he wrote in the New Yorker that, “the movie’s fabricated events shouldn’t lead any viewer to deny the historical facts of slavery and Reconstruction. But they also shouldn’t lead to a denial of the peculiar, disturbingly exalted beauty of Birth of a Nation, even in its depiction of immoral actions and its realisation of blatant propaganda.”

But the denial he seeks to avoid has already happened. The fact that the 100th anniversary of the film this year has been so studiously avoided by Hollywood and the Golden Globes Awards speaks volumes of its enduring power to shock, and the discomfort of both the film world and America more generally with confronting its troubled past when it comes to race and prejudice.

Attempting to understand and explore the social context in which racist ideas come from appears — in the 21st century — to have become a more difficult and exceptional task. Sadly, it seems that many would prefer airbrushing them away: deciding it’s better that people, in particular black people and those white masses ‘susceptible’ to racist ideas, avoid being exposed to the uncomfortable realities of the past.

However, we also have the examples of unheralded but important black filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux who didn’t back off from these challenges, but set about confronting the issues that agitated black and white audiences by telling alternative stories. In 1920, he created and produced Within Our Gates, a direct rebuttal to Griffiths’ propaganda. Micheaux’s emergence represents the first radical black voice in American film.

Kunle Olulode is director of Voice4Change England and film historian. He is speaking on Birth Of A Nation: more than racism on film? at the Battle of Ideas festival at the Barbican on 17 October. Index on Censorship’s director Jodie Ginsberg is also speaking on a session entitled Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?. Index are media partners of the festival.

9 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia

The return of Vladimir Putin as president of the Russian Federation in 2012, after a wave of protests, was followed by the implementation of a new law that required non-governmental organisations receiving foreign support — in the form of funding or material aid — and engaged in “political activity” to register as “foreign agents” with the Ministry of Justice.

There are currently eight organisations advocating for media freedom and journalists’ rights included on a black list of 86 NGOs. Among them are organisations fighting for access to information (Freedom of Information Foundation), providing legal support to journalists (Rights of the Media Defence Centre and Media Support Foundation (Sreda)), organising education for regional reporters (Press Development Institute – Sibir in Novosibirsk and Regional Press Institute), an information agency (Memo.ru) and others.

Foreign agents have additional responsibilities and duties, including having to report twice as often and providing more information to the Ministry of Justice than other NGOs. A notice reading “Published by an NGO – foreign agent” must mark everything they publish, although some refuse to comply. In the Russian language, “foreign agent” has strong negative connotations associated with Joseph Stalin’s Soviet-era political repression. Some would say the term implies that NGOs are spies or traitors.

Only one organisation in Russia had voluntarily identified itself as a foreign agent before July 2014 when new rules allowed the Ministry of Justice to put NGOs on the list as it sees fit.

Some of the media freedom organisations are in the process of shutting down, including Sreda and Freedom of Information Foundation, while others, such as the Regional Press Institute (RPI) in St Petersburg, continue their activities but are forced to pay large fines.

Anna Sharogradskaya, the director of RPI, says she would never register the NGO voluntarily. “Article 51 of the Russian constitution says that nobody is obliged to give incriminating evidence against himself or herself and labeling the RPI would be not only incriminating evidence, it would be slander on our donors,” Sharogradskaya says. “So why should I break the law?”

Since 1993, RPI has provided seminars for journalists from Russia’s northwest region, offered its facilities as a venue for independent press conferences and meetings, and organised discussions on topical issues.

The organisation has come under increasing state pressure. In June 2014, customs officers at the Pulkovo International Airport in St Petersburg detained Sharogradskaya and searched her luggage. She missed her flight to the USA where she had been visiting scholar at Indiana University. Her notebook, memory stick and other gadgets were confiscated without explanation. For more than 10 months, Sharogradskaya was suspected of terrorism and extremism, after which she was cleared of all charges and her belongings were returned — although not in working order.

In November 2014, Putin promised that the St Petersburg regional Ombudsman Alexander Shishlov would look into the RPI case. “And he did: some days after this meeting, the Ministry of Justice put my organisation on the list of foreign agents,” says Sharogradskaya.

A court in St Petersburg fined RPI 400,000 rubles ($6,150) for refusing of add itself to the list voluntary. Half of the amount was paid by Russian and international journalists around the world, and the rest was added from Sharogradskaya’s personal savings.

Despite the pressure, RPI continues acting as an independent help desk for journalists, giving the region’s media, bloggers, initiative groups, democratic opposition leaders, and activists an opportunity to raise their voice at press conferences, and advocating for those who are in trouble with the authorities.

Many, including Sharogradskaya, believe that Russian civil society, including the media, faces increasing pressure. NGOs advocating for the freedom of the press must now spend more time and efforts protecting themselves instead of protecting journalists and other parts of the media.

Sharogradskaya says that above everything else, the lack of solidarity among journalists is a major concern. “Our work is to raise this solidarity. This is the only way to withstand the time of repressions.”

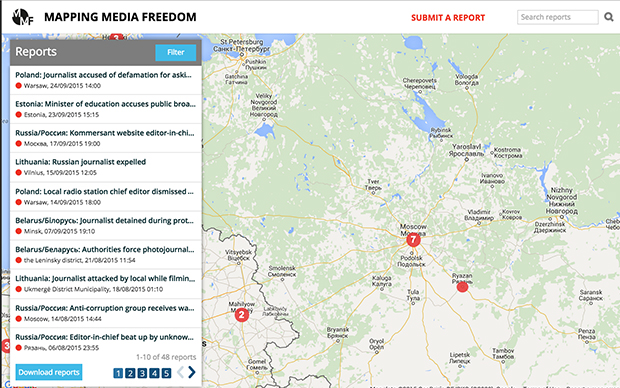

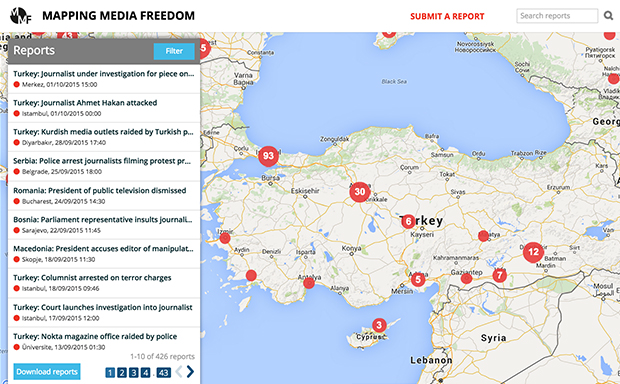

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

8 Oct 2015 | Campaigns, Mali, Press Releases

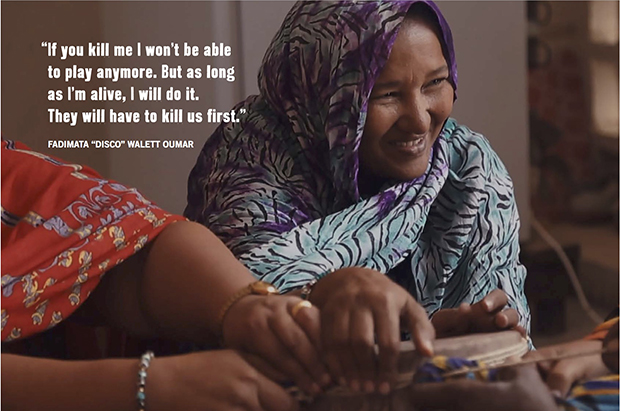

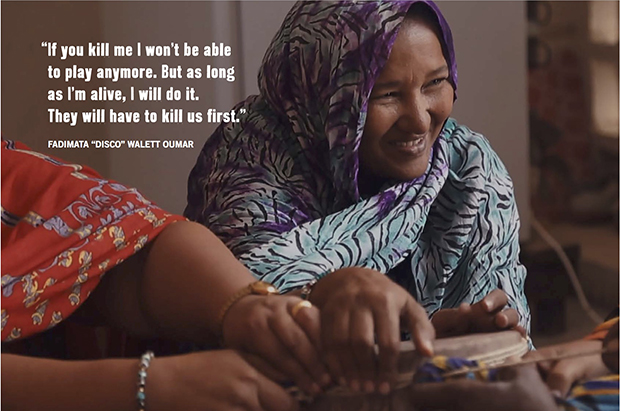

Fadimata “Disco” Walett Oumar, as featured in They Will Have To Kill Us First

Freedom of expression campaigners Index on Censorship and the producers of award-winning documentary They Will Have To Kill Us First are delighted to announce the launch of a new fund to support musicians facing censorship globally.

The Music in Exile Fund will be launched at the European premiere of They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile – a feature-length documentary that follows musicians in Mali in the wake of a jihadist takeover and subsequent banning of music – at the London Film Festival on 13 October.

In its first year, the Music In Exile Fund will contribute towards Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship, which is a year-long structured assistance programme to support those facing censorship. The funds will be used to support at least one musician or group nominated in the arts category of the awards. This will include attendance at the awards’ fellowship week in April 2016 – an intensive week-long programme to support career development for the artists. This also brings training in advocacy, fundraising, networking and digital security – all crucial for sustaining a career in the arts when under the pressure of censorship. The fellow will also receive continued support during their fellowship year.

Songhoy Blues, who feature in They Will Have To Kill Us First, were nominated for the arts category of the Index Freedom of Expression Awards in 2015. Index’s current arts award fellow is Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who releases music as El Haqed. His music publicises widespread poverty and rails against endemic government corruption in Morocco, where he is banned from performing publicly.

Johanna Schwartz, director of They Will Have To Kill Us First, said: “For the two years that followed the ban on music in Mali, I filmed with musicians on the ground, witnessing their struggles and learning what they needed in order to survive as artists. The idea for this fund has grown directly out of those experiences. When faced with censorship, musicians across the world need our support. We are thrilled to be partnering with our long-time collaborators Index on Censorship to launch this fund.”

Our ambition is to widen support as the fund grows to support more musicians in need.

You can donate to the Music In Exile Fund here.

For more details, please contact:

Index on Censorship: Helen Galliano – [email protected]

Mojo Musique: Sarah Mosses or Johanna Schwartz – [email protected]

8 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey

The top of Frederike Geerdink’s blog, Kurdish Matters, still reads: ‘The only foreign journalist based in Diyarbakir’. The Dutch reporter was the only foreign journalist in Turkish Kurdistan until 9 September 2015 when she was deported from the country she lived and worked for nine years.

“There I went in a military convoy, first from Yüksekova to Hakkari, then from Hakkari to Van,” Geerdink wrote a few days later. “As the soldiers were playing loud, rousing nationalist music, I realised that I had turned into a PKK target, being transported on a dark mountainous Kurdistan road in a military vehicle with windows too small to see the starry sky.”

From Van, she’d fly to Istanbul where she’d be forced on a plane back to her The Netherlands. A couple of days earlier she had been arrested while traveling with and reporting on the activities of a group of Kurdish activists who call themselves the Human Shield Group. She was accused of illegally entering a restricted zone and engaging “in an act that helped a terrorist organisation”.

After nine years in Turkey, three of which were in Kurdistan, Geerdink had lost her second home. “I left my heart in Kurdistan,” she posted on Facebook after she’d landed at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. “I don’t know when, but I will return.”

In the same week when Geerdink was deported, the English version of her book, The Boys are Dead, about the Roboski massacre and the Kurdish question in Turkey, was launched. “A coincidence,” she told Index on Censorship. “I don’t think the Turkish government had planned to help me promote my book.”

A few weeks after her ordeal, she was living a nomadic life in The Netherlands, moving from place to place, staying with friends or family, not really feeling at home anywhere. “I don’t want to be here,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong, everyone is really kind, but I don’t belong here anymore. I want to be there.”

Turkey has one of the world’s worst records on media freedom. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project has so far recorded 160 reports of violations against journalists in the country since May 2014. Reporters Without Borders has ranked Turkey 154th out of 180 countries on press freedom, and according to Freedom House, Turkey’s status declined from Partly Free to Not Free in 2013.

Reporting on the position of Kurds in Turkey is exceptionally difficult. Prominent journalists have been fired over their coverage of negotiations between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Kurdish and Turkish journalists are often targeted by the police and courts, although it is rare for a foreign journalist to be singled out.

Back in January 2015, Geerdink was arrested by the Turkish authorities for the first time. Her house was searched, she was briefly detained and faced up to five years in prison for ‘terrorist propaganda’. Her detention was condemned worldwide and she was acquitted of the charges in April. Her deportation just a few months later came as a big shock.

Now that even foreign journalists are being targeted, Geerdink said, shows just how bad things are for the position of Kurds in Turkey. “I was the only journalist based there and now there’s one less witness on the ground. And the fewer the witnesses, the more the state has a free hand.”

She added that her treatment should be a warning to others. “They are saying: ‘watch where you go or we’ll kick you out’.” On the other hand, she thinks her deportation brings a lot of negative publicity onto the Turkish government and how they treat journalists, which can be used to put more pressure on the authorities.

In September, two UK-based reporters for VICE were arrested while reporting in Diyarbakir. Although they were released, their Iraqi colleague remains in jail. Seven local journalists are currently detained in the country, many of whom are Kurds. Being a foreigner, Geerdink said the spotlight is on her, but there are many Kurds in prison who nobody knows about, and they deserve the same amount of publicity. “For them it is a matter of life and death.”

Geerdink hopes to return to Turkish Kurdistan as soon as she’s allowed back in. Her lawyers are working hard to appeal the verdict on her deportation. Meanwhile, she is focussing on Syrian Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan and Kurds in Europe.

“I will still be Kurdistan correspondent no matter where I am based.”

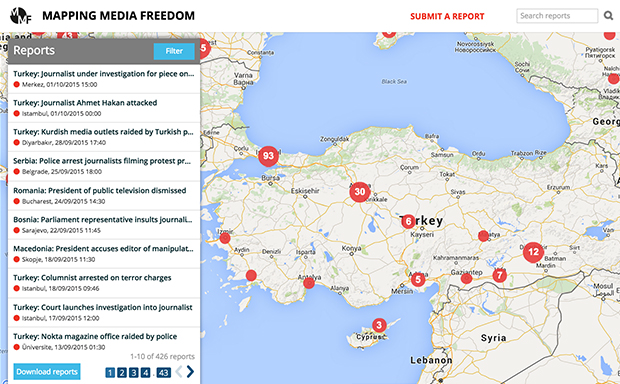

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|