25 Aug 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: On 25 August Aliyev was sentenced to pre-trial detention. A new charge of illegal entrepreneurship was filed against him, which carries a sentence of up to seven years in prison.

On 24 August Mehman Aliyev, director of independent news agency Turan, was detained and charged with tax evasion and abusing the authorities as part of a wider tax probe against the media outlet. On 23 August Aliyev was called into the state tax department where he was interrogated for eight hours.

“The arrest of Mehman Aliyev and the investigation into Turan have clear political motives. The Azerbaijani government has been exploiting law enforcement agencies to silence criticism and go after independent media,” Index’s head of advocacy Melody Patry said. “We call for the authorities to immediately release Mehman Aliyev and drop all charges against him. The judicial harassment against Turan news agency and its journalists must stop.”

The Azerbaijani authorities have been engaged in efforts to silence Turan news agency for months. On 10 August a tax probe was launched against Turan where the agency is being accused of under-declaring profits since 2014 and faces a fine of over 37,000 manats (€18,000). A week before on 16 August, the state tax department raided the outlet offices and confiscated documents. In April, authorities ruled to block access to Turan website which the courts upheld in May.

Turan has released a statement announcing the indefinite suspension of their work from 1 September as a direct result of blocks on their bank accounts as well as the detention of their director.

According to The Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, 15 journalists are currently in prison in Azerbaijan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503673643226-8608085a-6298-5″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Aug 2017 | Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

I spend a lot of my time writing about encryption. Until recently I did this from a UK perspective. That is to say, in a country where there are pretty good citizen protections. Despite the occasional hysterical article, the police don’t snoop on you without having some probable cause and a legal warrant. UK citizens aren’t constantly under surveillance and don’t get rounded up for speaking their mind.

From this vantage point, the public debate on encryption starts with its problems. Terrorists are using encrypted messaging apps. Drug dealers are using the Tor browser. End-to-end encryption used by the big tech firms is a headache for local police forces. All this is true. But any benefits are merely addendum, secondary points, “ands” or “buts”. Don’t forget, however, that encryption is also for activists and journalists, including those in less friendly parts of the world. Oh, and don’t forget ordinary citizens. Such benefits are mostly discussed abstractly, almost as an afterthought.

My view on encryption changed in 2016 when I was researching my book Radicals. This being a book about fringe political movements – often viewed with hostility by governments – I expected to use some degree of caution. But it was more than this. Over in Croatia, I was following Vit Jedlicka, the president of Liberland, a libertarian pseudo-nation on the Serb-Croat border. Jedlicka is trying to create a new nation on some unclaimed land that will run according to the principles of radical libertarianism, including voluntary taxation. The Croat authorities do not like him at all, even though he is non-violent and law abiding.

I arrived in Croatia, after an early Easy Jet flight, and was taken aside for questioning by the border police, who appeared to know I was coming. They told me not to attempt to visit Liberland. A little later, while I was away from my hotel, the police turned up and demanded a copy of my passport from the hotel manager. Jedlicka, meanwhile, was barred from entering Croatia, having been deemed a threat to national security.

I did not know a great deal about the Croatian police, but what little I did know made me doubt they cared too much about my right to privacy. I suddenly felt exposed. So Jedlicka and I communicated using an encrypted messaging app, Signal. I had considered Signal mostly a frustrating tool that helps violent Islamists avoid intelligence agencies. But suddenly this nuisance app was transformed. Thank God for Signal, I thought. Whoever invented Signal deserved a prize, I thought. Without Signal, Jedlicka couldn’t engage in activism. Without Signal, I couldn’t write about it.

This was in Croatia. Imagine what that might feel like as a democratic activist in Iran, Russia, Turkey or China.

You see the debate about encryption differently once you’ve had cause to rely on it personally for morally sound purposes. An abstract benefit to journalists or activists becomes a very tangible, almost emotional dependence. The simple existence of powerful, reliable encryption does more than just protect you from an overbearing state: it changes your mindset too. When it’s possible to communicate without your every move being traced, the citizen is emboldened. He or she is more likely to agitate, to protest and to question, rather than sullenly submit. If you believe the state is tracking you constantly, the only result is timid, self-censoring, frightened people. I felt it coming on in Croatia. Governments should be afraid of the people, not the other way around.

The debate on encryption, therefore, should change. The people who build this stuff – whether Tor, PGP or whatever else – are generally motivated by the desire to help people like Jedlicka, people like me. They don’t do it for the terrorists. Seen and understood in that light, the starting point for discussion is about the great benefits of encryption, followed by the frustrating and inevitable fact that bad guys will use the same networks, browsers and messaging apps.

Which is why any efforts to undermine encryption – through laws, endless criticism, weakening standards, bans, threats to ban, backdoors and international agreements – would hit someone like Jedlicka, or me, just as it would Isis. The questions then become: are we willing to prevent good guys having protection just because bad guys are using it? Once you’ve had cause to use it yourself, the answer is extremely clear.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503654311600-41f8449d-cfd3-2″ taxonomies=”6914″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Aug 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

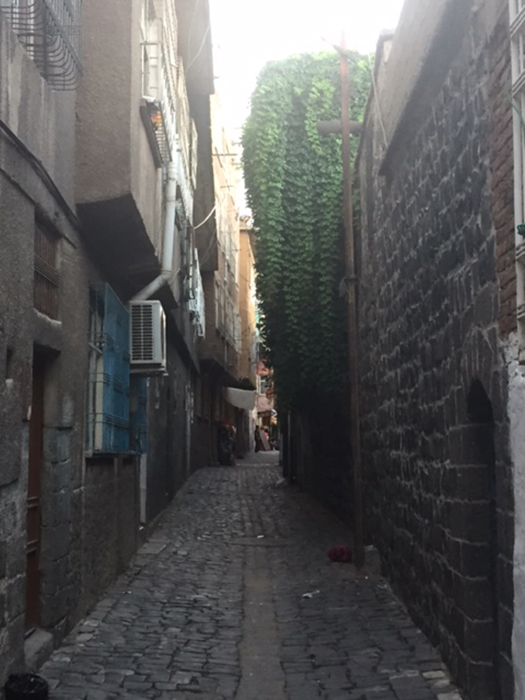

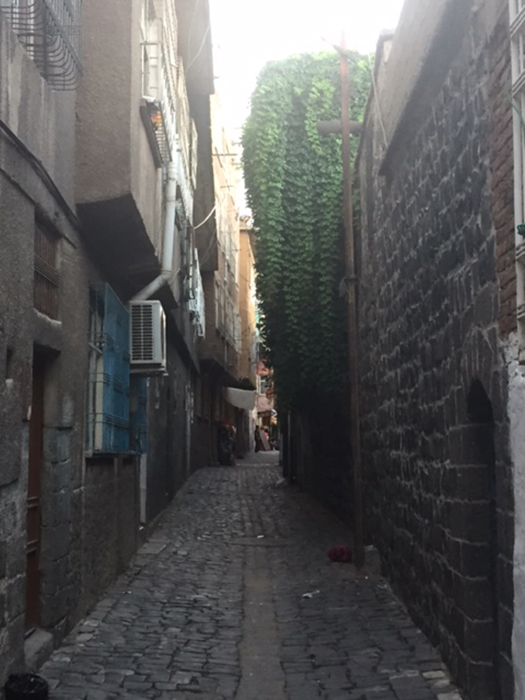

The district of Sur was the first settlement in Diyarbakır, which, according to some sources, has been inhabited for five thousand years and hosted 33 civilisations. The area’s architecture — a rich combination of churches and mosques, mansions and modest homes from different eras — is evidence of its long history and well-established community.

Since June 2016, parts of Sur have demolished as part of an “urban regeneration programme”. In the first stage, homes in the Sur neighbourhoods of Lalebey and Alipaşa were demolished. In the process, the primarily Kurdish communities were destroyed: some families moved away, their connections to their personal history severed; others stayed put, clinging to their homes and their lives in the neighbourhoods with a tenacious resistance to being erased.

The 2016 demolitions were the latest phase in a long process that began in 2009. That’s when the Mayoralties of Diyarbakır and Sur signed an agreement with Turkey’s Environment and Urban Planning Ministry and the Mass Housing Administration to replace the local housing stock with new homes in a style appropriate to the area. Beginning in 2011 with the bulldozing of homes of houses in the Alipaşa neighbourhood, the residents have been at odds with a government they see as inattentive and arbitrary.

During the 1990s, there were violent clashes between Turkey’s military and armed groups aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Thousands of villages were evacuated by state forces. Displaced people became impoverished when they settled in the city of Sur.

When the displaced began arriving in Sur, new housing was built that quickly overwhelmed the area’s mosque and architecture.

Historic buildings were destroyed in order to build housing for the displaced and the area quickly became a slum. In a short time, some of the new housing became unhealthy and unstable.

With neighbourhoods of historic buildings, narrow streets and local culture, the city of Sur would have lost these features through its urban regeneration project. Moreover, the money set aside to buy properties was not enough to allow people to start new lives elsewhere. As a result, the local government suspended the project.

Though the demolitions had been halted because the inhabitants of the area did not want to evacuate their homes and civil society organisations had objected to the destruction of the area’s history and community, an emergency decree issued after the failed July 2016 coup restarted the urban regeneration project.

In May 2017, authorities told residents of Sur’s Lalebey and Alipaşa neighborhoods to evacuate their homes. Families that resisted were told they would be forcibly removed. In the face of the threat, some families left the area. Those that remained had their water and electricity turned off.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Cumali, sitting in front of his evacuated house, did not want to leave Sur. He has been moved to temporary housing on a road that has not yet been demolished. Cumali says: “I was born in Sur, I grew up, got married. Let us relax. I want to die in Sur.”

Mevlüde Ak was born and grew up in a house in Sur. She gave her house in Sur to her married, unemployed son. She lives with her husband in their small shop. After closing time, they put down beds on the floor and sleep there. Mevlüde Ak says: “They offered me 60,000 Lira for our house. This money would not be enough for us to buy a new home. We’re not leaving. If they wish, let them bring it down on top of us.”

Aynur Güneş’s husband died years ago. She has no children. She lives by selling things like chocolate, gum, crisps in front of her house because it is close to a school. She explains why she does not want to leave Sur as follows: “I know nothing will happen to me here. If something happens: if I fall ill, for example, my neighbours will immediately come to help me. That’s how we grew up in Sur. If I have to live in an apartment I will die.”

Civil society organisations, supported by artists, journalists and politicians, have banded together with Sur residents to fight the ongoing destruction in the neighbourhoods. The campaign is helping to organise petitions and community gatherings, like this one breaking the fast during Ramadan.