[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The case study of the exhibition Eric Gill: The Body at Ditchling Museum of Arts & Crafts is different from the others in this section. In all the other cases, Index on Censorship got involved because artwork had been removed or cancelled, but in this case we were brought in at the early stage of the museum’s planning of an exhibition that was potentially divisive and controversial.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Name of exhibition: Eric Gill: The Body

Artist/s: Eric Gill and Cathy PIlkington, RA

Date: 29/04/17 – 03/09/17

Venue: Ditchling Museum of Art & Craft (DMAC)

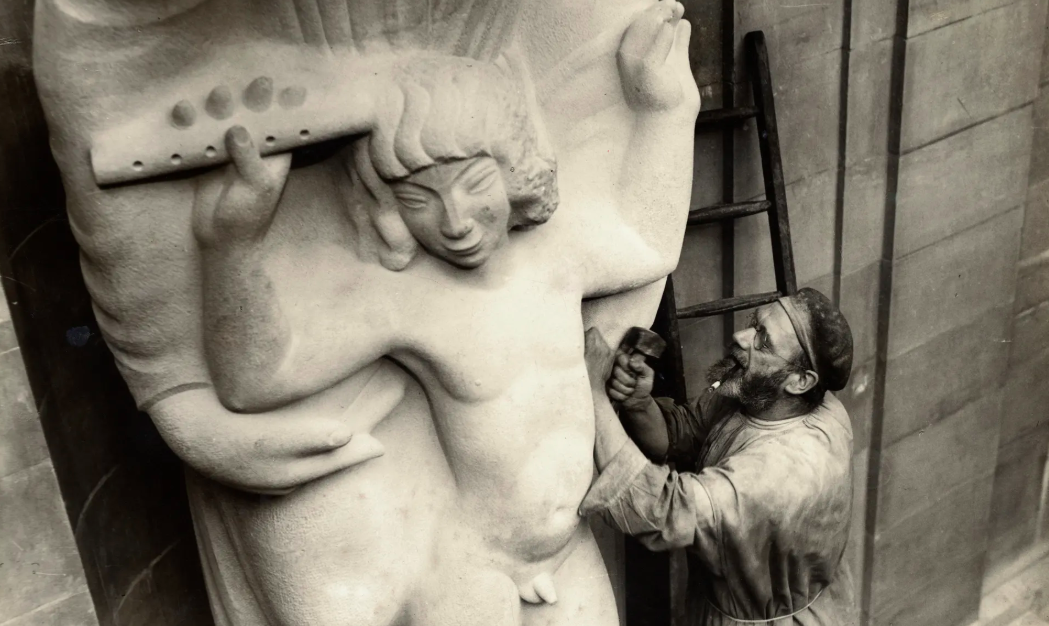

Brief description of the exhibition: “Co-curated by Cathie Pilkington, Eric Gill: The Body features over 80 works on loan from public and private collections including a new commission by Cathie Pilkington. Within Gill’s work, the human body is of central importance; the exhibition asked whether knowledge of Gill’s disturbing biography affects our enjoyment and appreciation of his depiction of the human figure.” DMAC Programme[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”106694″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The Ditchling Museum of Arts & Crafts wanted to use the summer exhibition 2017 as the platform to bring Eric Gill’s history of sexually abusing his teenage daughters centre stage. The case study records the process leading up to the exhibition which offers some interesting insights and positive ways of approaching difficult and sensitive subjects and includes some of the documentation that was produced that could be adapted for use in other situations.

Central to the planning was the workshop day – ‘Not Turning a Blind Eye’. This produced a lot of very interesting discussion and debate, in particular about the role of the museum as a place for difficult conversations. This has been recorded in detail and can be reached through a link in the case study. At the end there is a range of different responses to how the exhibition was managed, rather than looking at the content of the show, with a reflection from Steph Fuller, the new Director and CEO of Ditchling Museum, on the impact and legacy of the exhibition.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Why was it challenged?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Since the biography of Eric Gill by Fiona McCarthy, published in 1989, revealed that he had sexually abused his teenage daughters, awareness of this aspect of his biography is widespread and has been fully discussed and debated. In spite of this, DMAC, the museum which is effectively built around the Guild that Gill co-founded and of which he was its most famous protagonist, had not responded to the consequences of this revelation in their collection or their narrative. When Nathaniel Hepburn came to DMAC as Artistic Director in 2014 he was clear that he found the museum’s failure to take an open stance Gill’s sexual abuse of his daughters was problematic for a number of reasons.

- Inconsistency: some members of staff were able to talk to visitors about Gill’s disturbing behaviour, others found it difficult;

- Inappropriateness: a text panel describing Gill as ‘controversial’, where sexual abuse cannot have any moral ambiguity; a volunteer joking about Gill as a ‘naughty boy’ during a tour, because of an embarrassment or lack of knowledge.

- Unpreparedness: the museum would not have an answer if a visitor (maybe via social media or TripAdvisor), or the media or any other organisation were to question its moral or ethical standpoint regarding Gill.

- Self-censorship: there were objects in the collection that were not possible to exhibit because there was not necessary language, or confidence, to engage with the issues which would emerge.

- Failing in duty: the museums’ failure to provide proper contextual information about a nude of Petra, or a torso of Elizabeth [Gill’s daughters who were also his models], risked visitors’ trust in the museum. Either they visited with prior knowledge and felt DMAC was disingenuous; or they enjoyed Gill’s work and discovered later about his sexual abuse of his daughters, and then felt misled.

- Complicity: the staff were concerned that the silence could be taken as complicity. An all woman team with a male director, all bringing different experience, they felt a shared moral imperative to break the silence in relation to behaviour that is perpetuated by non-disclosure.

With difference of opinion across the team and trustees, and knowing how Gill’s continued respect as a major 20th century British artist, in spite of the revelations about his sexual abuse of his daughters, also divides public opinion, it was clear that this project was not going to be about the museum agreeing a place in the debate. It would have to be about the debate itself. There was a lot at stake. If it was handled clumsily it could cause distress to survivors of abuse, could be sensationalised in the press and risked more reputational damage than the museum’s long silence on the issue. The ongoing stream of revelations exposing the prevalence and scale of sexual abuse of children across society heightened the sensitivity and enormity of the issue, and the risk of getting it wrong. If successfully handled, then DMAC’s openness could send out a positive message across the sector for other museums to be proactive in finding ways of taking on difficult stories and objects within collections to stimulate rather than avoid debate with visitors and the wider public. The aim to create a well-researched space, designed to support dialogue, where all opinion on the issues raised could be held and handled with confidence, required considered discussion and preparation about language, terminology, financial and reputational risk, about relationships with stakeholders, visitor experience, communications, supporting staff and more.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”What action was taken?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Partnership

Hepburn secured Brighton Festival as a partner early in the process. The festival’s reputation for taking on political issues connected DMAC to wider territory than it could occupy by itself which, by association, helped frame communication with the public. It also acknowledged that the issues DMAC was tackling extend far beyond the museum and its very particular relationship with Gill.

Commission

Hepburn commissioned Royal Academician, Sculptor Cathie Pilkington, in partnership with Brighton Festival, to respond to the themes of the exhibition. She took the contentious object known as Petra’s doll, made by Gill for his daughter’s 4th birthday, as the inspiration for her work. Pilkington was considered to be an ideal choice, a strong woman artist engaging with these themes as another way to respond to Gill’s life and work and the collection in the museum as a whole.

Consultation with survivors of abuse

Hepburn spoke very early on about his plans to Peter Saunders, a survivor of abuse and founder of the National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC). Saunders became an ally, willing to speak in support of the project to the media. Hepburn had meetings with four charities, to give them advance information about the forthcoming show, why DMAC felt it was important to do it and to ask for advice on language and what kind of responses the work might provoke. One of the four was not supportive and spoke out against the show to the media.

Workshop with peers

Not Turning a Blind Eye was a carefully structured workshop day bringing together museum professionals, curators, lawyers, journalists, academics to respond to specific objects and artworks in the collection. The workshop took place in October 2016 and was structured around the presentation of contentious pieces in the collection – to discover first-hand what questions and feelings they provoked; and to discuss whether and or how they could be exhibited. Other ethical challenges that the staff encounter on a daily basis were also posed and discussed. The workshop elicited strong and insightful responses from different disciplines and approaches and voicing clearly articulated positions and options for Hepburn and the staff to consider. A detailed description of the workshop can be found here.

Staff, volunteer and trustee preparation and training

Hepburn brought new trustees on board, sought out individuals and organisations from outside the museum who could share their expertise and experience; the staff took every opportunity to talk amongst themselves, with friends and colleagues. The museum’s approach was characterised by transparency, openly acknowledging and sharing dilemmas, seeking advice, talking to a very wide range of people. There was a lot of training for staff and volunteers with sessions run by charities supporting survivors of abuse. There was preparation for every eventuality and audience response:

- defacing the artwork, protests, upset, anger, triggers. Front of house staff informed every audience

- member at point of sale that the the exhibition invited the audience into the debate. There were

- helplines and support literature for people who could have been adversely affected by the content of the show.

Communications

The goal of the exhibition was to generate dialogue with a broad range of constituents – media, general public, visitors, survivors, and stakeholders, with members of the Gill family, family members of the original Guild still living in the village and others. The idea was not to ask permission, but to talk about the planned programme and invite feedback. The decision to involve multiple stakeholders in the planning of the exhibition helped shape the way the artwork would be discussed and showed there was no single answer to the dilemmas that Gill’s story throws up. Arriving at a shared sense of how to talk about the exhibition and to respond to audience questions and reactions was a major area of work. A series of documents were created – here are some examples: Director’s statement; FAQ; Gill terminology; and any complaints were dealt with fully and personally by the director. A series of procedures were created for staff and volunteers to follow in the case of adult or child disclosure and a complaints procedure.

Managing the media

Hepburn made the first mention of his plan in an article Self-censoring Museums Have to Be Braver in the Art Newspaper by Maurice Davies who Hepburn knew would not sensationalise the issue. Though Hepburn has since spoken publicly, lectured and written extensively on the subject, he remembers “agonising” over the words he used to describe the museum’s position

in that first outing. Another important move in the press strategy was to commission Observer columnist and art critic, Rachel Cooke (see extract below) to follow the process from the start. The idea was that the article, published before the opening, would open up museum’s approach, leading to an honest discussion with the public.

Writers in Residence

Two writers in residence were commissioned to respond to the exhibition, bringing additional artistic voice to explore and process the exhibition. When writer Bethan Roberts saw the exhibition she felt that the voices of the women particularly the daughters in it were missing and in response decided to write Petra’s story. Alison Macleod based her response on the wide-ranging responses on the audience feedback which ranged from “Disgusted!” and “Elated!”. In response she wrote “something that [is] multi-voiced, multi-perspectival” to get at the complexity of the subject matter.

More information about the writers in residence project, and extracts from the work created can be found here.

Audience feedback

There were 316 comments submitted on the feedback postcards, all of which have been transcribed – a sample of them can be found here. Some visitors praised the DMAC’s handling of the issues: “I believe the exhibitors have struck the right balance: the genius of the artist, and the honesty in depicting his sexual abuse, are both necessary and well represented. I love the work still, but have no illusions about the artist.” Others condemned it: “Angry at the focus on Gill’s behaviour with no acknowledgement of its impact on the lives of his daughters.” The front of house staff had the most face to face contact with the visitors; many wanted to talk about the show. There were lots of different reactions. “It showed human nature in all its forms. Some said – what’s the fuss? why does it have to be shoved in our face? we’ve known this for years. This is brilliant! One or two wanted more of the survivor story – expecting more from the [survivors] network. Several said it was not shocking enough. One told me ‘I’m survivor of abuse and I was interested to come and see how you were presenting it.’”

A catalogue was produced after the end of the show.

Press coverage Eric Gill: The Body.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Interviews” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship carried out a series of interviews with a range of stakeholders including the staff and trustees. Here are some extracts:

Cathie Pilkington, RA – artist, co-curator of Eric Gill: The Body.

There are different kinds of risk to this [commission]. I felt I had to go with that initial intuitive response, my genuine engagement with the doll [carved by Gill for his daughter’s 4th birthday] and with the dilemma. As an artist you have to trust those drives towards things, even though they are risky. Quite a few people said, don’t do this, don’t put yourself in this dilemma, you are making yourself vulnerable and actually there is part of that you are being used as a resource to mediate something. But I recognised it as well and I knew that I was the right artist to do this regardless of the difficulties that I might have. I came away [from the workshop] very excited and elated by realising that there was a moral responsibility of the artist to allow these things to happen and for speech to be open. It was exciting to see a real role for art. It as as much about that, as the subject of the abuse and the problems associated with the project.

Alice Purkiss – leader of Trusted Source Knowledge Transfer Partnership between Oxford’s History Faculty and the National Trust (2016-2018)

They told the story with utmost sensitivity but without censorship and I think that was an important factor. It wasn’t salacious which it could have been. It wasn’t accusatory. It was quite frank and objective and I was interested in their use of language in the show. A lot of colleagues will see this as an opportunity to see what goes into the process – more will have the confidence to do this themselves.

Andrew Comben – Director of Brighton Festival and board member

Collectively and Nathaniel particularly managed it brilliantly, sensitively thoughtfully and patiently. It felt like a textbook example of how to navigate all this territory. I am also interested now in hearing that museum professionals see it as a sort of blueprint of how to manage sensitive issues. Embedding a journalist in the process and having someone follow that right from the start so there could be a public conversation and an honest one I thought was very smart. Talking to charities working in the territory, not of the arts world was something all too frequently arts organisation don’t do. [Ref partnership with Brighton Festival] It seems something really obvious and quite straightforward, that maybe organisations don’t have to go it alone when they addressing these sorts of things and there is strength in a collective response.

From Rachel Cooke’s detailed account published in The Observer before the show opened: Eric Gill: can we separate the artist from the abuser?

“Hepburn’s decision to mount Eric Gill: The Body might be thought rather brave – and certainly this is the word I hear repeatedly from those who support his project… But still, I wonder. Is it courageous, or is it merely foolhardy? And what consequences will it have in the longer run both for Gill’s work and those institutions that are its guardians? Is it possible that Hepburn, in fighting his own museum’s “self-censorship”, will start a ripple effect that ultimately will see more censorship elsewhere, rather than less? And once Gill is dispensed with, where do we go next? Where does this leave, say, artists such as Balthus and Hans Bellmer? Even if their private lives were less reprehensible than Gill’s, their work – that of Balthus betrays a fixation on young girls, while Bellmer is best known for his lifesize pubescent dolls – is surely far more unsettling.”

Peter Saunders – NPAC

They were bold in saying that whilst he was an artist and produced works of some significance he also admitted to some extremely nasty crimes against his own children. I felt positive with their approach. When we are talking about something that goes back quite a long time and there are no living victims of these people, then it is slightly different from dealing with someone who is uncovered as being a current abuser and thereby is likely to have living victims who will still be living with the trauma probably and of what had been done to them by the individuals. It therefore calls for a slightly different approach. My opinion is that if we were to actually delve into the lives of many people of prominence from the past we would potentially uncover some pretty unpleasant stuff I expect. Does that change the quality or significance of what they contributed to the arts or whatever it was? Or do we ignore it, do we acknowledge it or sweep it under the carpet?

Alison McLeod – writer in residence

There doesn’t seem to be one point of view on it, the more I looked into the more complex it became, and my own point of view is irrelevant in a sense, it’s not even what guides the writing project. Yes, the biography is upsetting disturbing in part and there was clearly a history of abuse that is without question. But it is made slightly more complex by the fact that the two daughters were abused said they were unembarrassed about it, not angry about it, loved their father, and didn’t give the response that perhaps I’m imagining, or some people expected them to give – to be angry about it and condemn their father’s behaviour. They didn’t. So maybe they have internalised their trauma, but you could say that that response is almost patronising to the two women, the elderly women who were very clear about what they felt, so it goes into a loop of paradoxes of riddles that you cannot really ever solve.

Nathaniel Hepburn speaking three weeks into the process.

I have underestimated the emotional strain on the team that delivering this project, and continuing to deliver it for the next four months, has caused and will continue to cause and the amount of time needed to hold the team through that process. We are looking out for each other and that is going to have to continue. Although we have put in place everything that was needed I think it will continue to be an issue for the next four months. That we cannot quite switch off. I am really lucky to have a great, supportive team and that we will be OK.

Staff feedback

So many of the things we [DMAC staff] put into place, structures, approaches which we talked about and rehearsed and gone over and over, language, openness and confidence in being open about it, willingness to engage, not justifying, or defending, or shutting down – all those things – I have seen them played out.

The Founder of NAPAC came to talk to the staff about how someone who had been abused would feel about coming to this show. He told his own story and he had been abused. But actually it was good to have a survivor in the room and to hear the incredibly negative impact it had had. Although it was hard, it brought people together.

We didn’t give our own opinions; we were being professional. This is what we are doing and we hope we have done it well. When people knew that it had taken 2 years and we had thought so carefully about it, it helped.

Yes we’ve done it, we’ve done it pretty well and it had to be done and we have put so much in place and so many discussions, such sensitivity about how it was going to be done. Everyone’s voice, concerns and anxieties from members of staff have found a way through into this.

Over the first weekend there were lots of visitors, and positive feedback, good that you’ve done it – rather than beautiful exhibition. There was discussion going on in the café afterwards. More children than expected. Teenage daughters with their mums. That made me feel proud. That’s a good conversation to have, brings the abuse out into the open…

It got more difficult as the show went on – he was on the inside and I got really sick of it by the end – it [the end of the show] is a weight lifted off our shoulders.

We have all had to cover for front of house. It’s exhausting – giving everyone the time and attention they need. The flippant comments, people trying to make light – that was quite difficult to hear again and again.

I wasn’t sure I wanted to do this – how dare he [Gill] put me in this position every day and think about this, as the mother of a young daughter, but in fact it was very interesting to work.

There was lots of mutual support – helps that it is a small team that gets on. Individuals checking in on each other – backing each other up – we have all had our moments.

Now that we are getting positive responses and level of engagement is really encouraging I feel much more confident about communicating it. The biggest concern would be to get people outside and faced with an anger that is difficult to be rational with. It didn’t happen but there could still be a reaction. 3 weeks in – and I’m trying not to be complacent – I am still prepared. The first week was the most intense – but it has dried up for the past couple of weeks.

After this exhibition, and the learning that we have undertaken as a result, we will reflect on how the permanent collection displays can incorporate this information so that the museum does not turn a blind eye to Gill’s more disturbing biography again.

Reflection – Steph Fuller Artistic Director Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft

A few observations, being on the outside and being recruited while the show was on:

I thought it was a good thing for the museum to do; it was important not to hide from issues. I felt that, within the exhibition, if the public didn’t read all the background material, watch the film and the discussions, they could miss quite a lot of the nuance of what was happening and I thought that was a pity. People in the museums and galleries business, who did read all of that stuff and listened to it and who knew much more about the process [had one kind of experience]. But I think the visitor experience was a bit partial in the museum.

The real legacy issue, which I am grappling with at the moment, is that the voice that was not in the room, was Petra’s. She was very front and centre as far as Cathie’s commission was concerned, but there is something about how the work conflated Petra with the doll and being a child victim, that I’m a bit uncomfortable about actually. There is lots of evidence of Petra’s views about her experiences, and how she internalised them, that was not present at all anywhere. It is easy to project things on to someone being just a victim and Petra would have completely rejected that.

In terms of legacy how we continue to talk about Gill and his child sexual abuse and other sexual activities which were fairly well outside the mainstream, I think – yes acknowledge it, but also – how? I am feeling my way round it at the moment. There are plenty of living people, her children and grandchildren who are protective of her, quite reasonably. I need to feel satisfied that when we speak about Petra, we represent her side of it and we don’t just tell it from the point of view of the abuser, to put it bluntly. If it is about Petra, how do we do it in a way that respects her views and her family’s views?

I feel very much it’s a piece of work that is not done. But the thing to do is to start. It’s much better to do something than to do nothing, then expose the next layer of issues which need to be addressed.

In terms of the staff, I think some of the staff were quite damaged by the experience of having to deal with it, and it would have been good if there had been more psychological, emotional support for staff in place. For most people, they accepted that it was difficult, but it was important and everybody got on with it. But it’s really hard to work with it all the time and I am thinking about doing more internal work for staff, and as new staff come in – this is never going away.

It was quite a high risk thing for the museum to do and for a lot of people who had nurtured the museum over a long time there were concerns about if this was the right thing to do, or the right way to do it. I think quite a few of the trustees breathed a deep sigh of relief when it had happened, that it had been OK; the museum had been recognised and applauded for doing it, much more than people who had thrown bricks at it, and that was a result. We have had to talk round a couple of people in the village who said they would never have anything to do with the museum again – and we managed to lure them back in, this is one aspect of what we are about, but we are still the place you are supportive of.

The exhibition absolutely is informing our future thinking around interpretation and how we tell that narrative about Eric Gill and the Guild, and subsequently. I don’t want it to be the only thing that people ever think about in the context of our content. Gill is very important and an important part of the museum’s story, but there is a huge amount of other stuff and other artists and a much longer history for us. We’ve had a run of shows that have been looking more at women and that’s a sort of balancing act, certainly internally. There is a show coming up when we will be looking at material from our collection. We will need to be some new interpretation and that’s a useful next step, putting in a tangible form the things that have been learned and thought about and mulled over as a result of doing the exhibition.

At the beginning, I asked myself – what is my position on this? In many ways – I don’t feel it is a black and white thing. I love Eric Gill’s work, I loved it before we knew that he was a child sex-abuser, obviously I have known that for a very long time, and, having thought about it a lot, I still feel that the work is interesting and valid. I am able to think about the work in a way that is detached from his behaviour, which is very much not acceptable. Post #MeToo there is a real desire for a binary position: ‘this is wrong’ and therefore everything that has anything to do with it is wrong, and therefore we should whitewash Eric Gill and his work out of our collection, we should never show his work or speak of him again. I think that’s not helpful and makes no sense to remove someone from the narrative, who is really important and influential in art historical and in philosophical terms. We couldn’t talk about what the museum is about without talking about Eric Gill. It’s not doable.

While I have a critique of the work, I I am not in any way critical of Nathaniel doing the show; I think it was a really great thing Nathaniel did to do and very courageous. It was about moving the narrative into the public space and that was the big step. It was done in a way that managed it pretty effectively for the museum, although there have been some very negative responses. Overall, the museum has been respected for doing things in the way they did, even by some people who don’t altogether agree with where it landed. I think there are things that could have been handled differently that might have added some extra layers of complexity in some respects, but maybe you can only deal with so much complexity at once. If I had approached this and done it from scratch, I would have done it in a different way and it would have been flawed in another way – there is never a perfect answer.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”Case Studies” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”15471″][/vc_column][/vc_row]