12 Feb 2019 | Europe and Central Asia, Index Reports, News and features, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Britain’s new counter-terrorism bill, which passed into law on Tuesday, threatens freedom of expression, free speech group Index on Censorship has warned.

While lawmakers and the public focused on Brexit, the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill slipped through parliament with far too little attention from politicians.

“The Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act crosses a line that takes the law very close to prohibiting opinions,” said Index on Censorship’s Head of Advocacy Joy Hyvarinen. The act criminalises expressing an opinion or belief that is “supportive” of a proscribed (terrorist) organisation if done in a way that is “reckless” as to whether it encourages another person to support a proscribed organisation. “This is a very dangerous legislative step to take in a democratic society,” Hyvarinen added.

Index on Censorship is also concerned about the implications of the new legislation for press freedom in the UK. It is now an offence to publish a photo or video clip of clothes or an item such as a flag in a way that raises “reasonable suspicion” (a low legal threshold) that the person doing so is a member or supporter of a terrorist organisation. This is highly likely to restrict and encourage self-censorship of journalistic activities. The clause also covers posting pictures on social media which have been taken in a private home.

In relation to press freedom, Index is also particularly concerned about the wide-ranging new border security powers contained in Schedule 3, which lack adequate safeguards to protect journalists and their confidential sources. The draft Code of Practice that will guide implementation of Schedule 3 must be strengthened to safeguard press freedom.

Index has, however, welcomed the government’s announcement during debates on the bill that it will undertake an independent review of the Prevent strategy, which Index had called for.

Background

The sections below highlight some of Index on Censorship’s concerns with the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act.

Index on Censorship began campaigning against the bill (draft law) as soon as it was introduced in the Parliament of the United Kingdom last summer because of its damaging implications for freedom of expression, including press freedom.

International concerns

The bill was widely criticised in the UK and also raised international concerns. The Media Freedom Representative of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) wrote to the UK authorities to express concerns and recommend changes to protect journalistic activities. United Nations special rapporteur Fionnuala Ní Aoláin stated that the bill needed to be brought in line with the UK’s obligations under international human rights law(1). Index filed an official notification with the Council of Europe’s platform for the protection of journalism about the bill’s implications for media freedom in the UK.

Small improvements: not enough

Index was pleased that some MPs and peers proposed amendments and argued for changes to safeguard freedom of expression. This led to some improvements to the bill, such as explicit recognition that carrying out work as a journalist or carrying out academic research is a reasonable excuse for accessing material online that could be useful for terrorism (see Clause 3).

Index also welcomed the government’s announcement that it will undertake an independent review of the Prevent strategy. Index and other organisations campaigned for such a review.

However, the improvements were not enough and Index remains very concerned about the impacts of the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act on freedom of expression.

Reckless expressions of support for a proscribed organisation (Clause 1)

This clause criminalises expressing an opinion or belief that is “supportive” of a proscribed organisation if the person does so in a way that is “reckless” as to whether it encourages someone else to support a proscribed organisation.

This is a vague and unclear clause that comes far too close to criminalising opinion.

The clause risks closing down democratic debate. The Joint Committee on Human Rights pointed out: “It is arguable that clause 1 could include, for example, an academic debate during which participants speak in favour of the de-proscription of currently proscribed organisations.”(2) The News Media Association (NMA) pointed out: “It is easy to envisage a similar debate taking place among commentators on the pages of the UK’s newspapers.”(3)

The government decides which organisations are included on the list of proscribed organisations (see below). Legislation that could discourage someone from arguing in favour of removing an organisation from the list, for fear that it could be viewed as “supportive” and “reckless”, is deeply concerning from a freedom of expression point of view.

Proscribed (terrorist) organisations

The Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act expands crimes related to organisations on the government’s list of proscribed organisations.

At the time of writing there are 88 proscribed organisations, including 14 in Northern Ireland. Proscription has significant consequences, including on freedom of expression.

The Home Office has informed Lord Anderson, the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, that at least 14 organisations (4) do not meet the criteria for proscription. In other words, they should not be on the list.

An organisation can be removed from the list by applying to the Home Office. The very high legal costs involved, especially if it involves appealing a decision to refuse deproscription, are likely to be a significant obstacle. Only three organisations have been deproscribed (5).

During debates on the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill Lord Anderson proposed an amendment that would have required an annual review of proscribed organisations. This amendment was unfortunately not accepted.

Publication of images (Clause 2)

This clause criminalises publication of pictures or video of an item of clothing or an article such as a flag in a way that raises “reasonable suspicion” (a low legal threshold) that the person doing so is a member or supporter of a terrorist organisation. The clause covers posting pictures on social media which have been taken in a private home.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights found that the clause “risks a huge swathe of publications being caught, including historical images and journalistic articles”(6). United Nations rapporteur Fionnuala Ní Aoláin expressed concern that the clause risks criminalising “a broad range of legitimate behaviour, including reporting by journalists, civil society organisations or human rights activists as well as academic and other research activity”(7).

Obtaining or viewing material over the internet (Clause 3)

This clause makes it an offence to view or otherwise access information online that is likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing acts of terrorism. No terrorist intent is required.

Index is pleased with the recognition, following debates in parliament, that carrying out work as a journalist or carrying out academic research is a reasonable excuse for accessing material online that could be useful for terrorism.

However, the clause remains very problematic. Anyone who wanted to understand terrorism and its causes better could be caught by the clause; for example someone who was concerned that a family member was at risk of being attracted to terrorism.

In a submission related to this clause, Max Hill QC and Professor Clive Walker stated: “[T]he inherent claim is that viewers will either be seduced or have their will overwhelmed by the inevitable power and persuasion of the terrorist messages […] Yet, other outturns are statistically more likely by far.”

Hill and Walker highlighted that the government and researchers have repeatedly asserted that there is no clear production line from viewing extremism or even being “radicalised” into becoming an active terrorist (8). United Nations rapporteur Ní Aoláin made the same point noting “the danger of employing simplistic “conveyor-belt” theories of radicalization to violence, including to terrorism”(9).

Schedule 3 – border security powers

Schedule 3 introduces new border security powers, aimed at “hostile activity”. This is a vague and unclear concept, which is combined with very wide, intrusive new powers to stop, detain and search.

For example, under Schedule 3 a journalist who catches a domestic flight could be stopped without there being any suspicion that she or he had engaged in hostile activity. It is an offence not to answer questions or provide any material requested. At this point there are no protections for confidential journalistic material. It is extremely important that the draft Code of Practice that will guide how Schedule 3 is put in practice is strengthened to safeguard journalistic sources and press freedom.

Northern Ireland

During the passage of the bill, the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) identified a catalogue of problems in the bill related to Northern Ireland, which also threw its general flaws into sharp relief. As a CAJ briefing paper noted:

“We can quite properly criticise this draft legislation for criminalising what could often be innocuous or trivial behaviour. When looked at in the light of Northern Ireland reality, however, it looks grossly disproportionate if not ridiculous (10). […] The idiocy of applying these measures to Northern Ireland ought to give legislators pause for thought before they pass them for the whole of the UK.”(11)

It is regrettable that the majority of lawmakers do not seem to have paused for thought.

Contact: Joy Hyvarinen, Head of Advocacy, [email protected]

(1) Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, Submission, House of Commons Public Bill Committee, OL GBR 7/2018, 17 July 2018, para.5.

(2) Joint Committee on Human Rights, Legislative Scrutiny: Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill, Ninth Report of Session 2017–19, para. 12.

(3) News Media Association, Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill: Briefing for the House of Lords, Second Reading, p. 1.

(4) This figure does not consider the 14 Northern Irish organisations, which may also include ones that do not fulfil the criteria for proscription.

(5) The Peoples’ Mujaheddin of Iran in 2008, the International Sikh Youth Federation in 2016 and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin in 2017. The Red Hand Commando has recently applied for deproscription. Reportedly the application was rejected.

(6) Note 2, para. 26.

(7) Note 1, para. 14.

(8) Max Hill QC & Clive Walker, Submission in relation to Clause 3 of the Counter Terrorism & Border Security Bill 2018, July 2018, para. 2(a).

(9) Note 1, para. 17.

(10) Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ), 2018, 9 August 2018, Briefing on the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill, para.8.

(11) Above, para. 13.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567076180113-10dba29d-3162-2″ taxonomies=”21″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Feb 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Press Releases

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Press freedom in Europe is more fragile now than at any time since the end of the Cold War. That is the alarming conclusion of a report launched today by the 12 partner organisations of the Council of Europe platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists.

The report, “Democracy at Risk”, analyses media freedom violations raised to the Platform in 2018. It provides a stark picture of the worsening environment for the media across Europe, in which journalists increasingly face obstruction, hostility and violence as they investigate and report on behalf of the public.

The 12 Platform partners – international journalists’ and media organisations as well as freedom of expression advocacy groups – reported 140 serious media freedom violations (“alerts”) in 32 Council of Europe member states in 2018. This review of the alerts reveals a picture sharply at odds with the guarantees enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights. Impunity for crimes against journalists is becoming a “new normal”. Legal protections for critical, investigative reporting have been weakened offline and online. The space for the press to hold government authorities and the powerful to account has shrunk.

Last year the murders of Ján Kuciak and fiancée Martina Kušnírová in Slovakia and Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, were among 35 alerts for attacks on journalists’ physical safety and integrity. Alerts about serious threats to journalists’ lives doubled and were accompanied by a strong surge in verbal abuse and public stigmatisation of the media and individual journalists in Council of Europe member states.

“Urgent actions backed by a determined show of political will by Council of Europe member states are now required to improve the dire conditions for media freedom and to provide reliable protections for journalists in law and practice”, the report warns.

The purpose of the Platform, based on a 2015 agreement between the Council of Europe and the partner organisations, is to prompt an early dialogue with member states and hasten remedies for violations and shortcomings in the protections for free and independent journalism.

The Platform partners call on states that impose the harshest restrictions on journalists’ activities’ and freedom of expression to:

- Restore rule of law safeguards and drop charges against journalists and release them as a step towards restoring a safe and enabling environment for independent media;

- Remove extremism and other laws criminalising media and end arbitrary exercise of powers by the executive and regulators; and

- Take the necessary steps to put in place a structure of media regulation and ownership which safeguards media plurality and freedom.

In addition, the Platform partners call on all states to reply fully and in good faith to all alerts and to take effective measures in law and practice to remedy the threats to the safety of individual journalists and media.

The Council of Europe Platform was launched in April 2015 to provide information which may serve as a basis for dialogue with member states about possible protective or remedial action. While many member states responded to alerts in 2018, five states declined to respond to any alerts, including those reporting very serious media freedom violations.

The 12 Platform partners are: the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the Association of European Journalists (AEJ), Article 19, Reporters without Borders (RSF), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Index on Censorship, the International Press Institute (IPI), the International News Safety Institute (INSI), Rory Peck Trust, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and PEN International.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549970814170-cd3c7b7a-5d5e-10″ taxonomies=”208″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Feb 2019 | Magazine, News and features, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Forty years ago, on 11 February 1979, the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, came to an end after millions of Iranians, from all backgrounds, took to the streets in protest at what they saw as an authoritarian, oppressive and lavish reign.

After decades of royal rule, and following 10 days of open revolt since the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to the country after 14 years of exile, Iran’s military stood down. With Pahlavi forced to leave the country, the Islamic Republic of Iran was declared in April 1979.

Here Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the revolution, an event that has since shaped the entire Middle East and has had a lasting impact to this day.

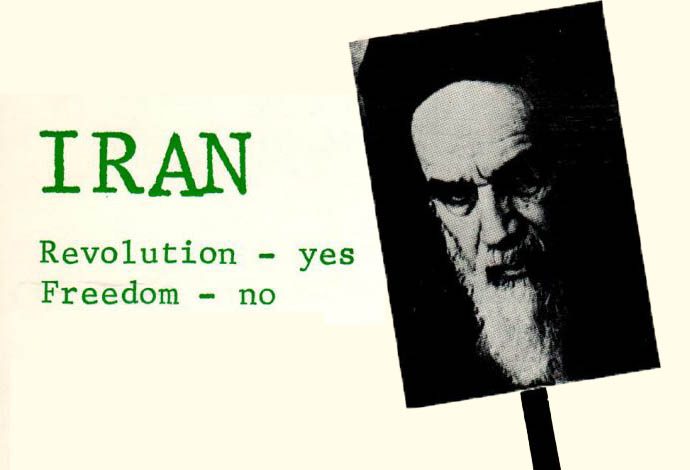

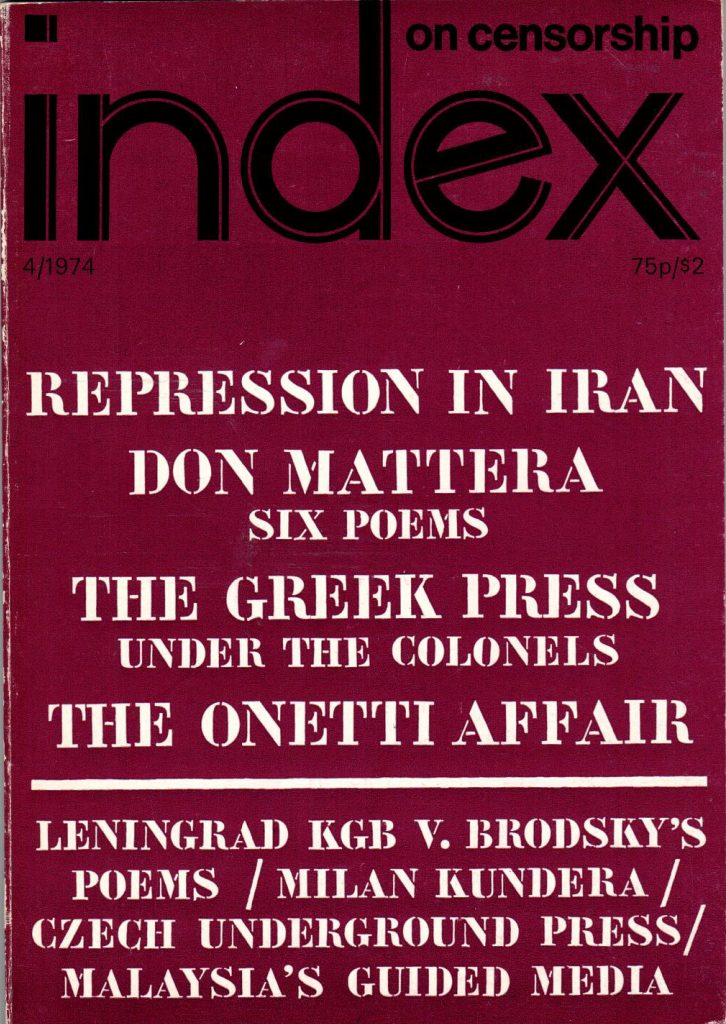

Repression in Iran , the Winter 1974 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Repression in Iran

Ahmad Faroughy

December 1974, vol. 3, issue 4

In October 1972, the shah of Iran celebrated the 2,500th year of Persian Monarchy which, despite twenty national dynastic changes, has constantly endeavoured to remain Absolute. Although the aim of this article is not to debate the political merits and demerits of autocracy as a means of government, it is obvious that whatever minor benefits Iran may have derived from hereditary dictatorship, freedom of expression is certainly not one of them.

Read the full article

China: Unofficial texts, the September 1979 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

The press since the shah

M. Siamand

September 1979, vol. 8, issue 5

The Muslim clerical establishment had not been decimated, and the various peoples of Iran, showing a remarkable unanimity, rallied behind the exiled Ayatollah to overwhelm the imperial army into submission by staring it In the face. What the great majority of observers regarded as impossible has come to be: the minority cultures seem no longer in danger of quick extinction, and everyone is engaged in an exhilarating debate about the future. But unfortunately, threatening clouds can be seen gathering on the horizon. The revolution has not yet started to devour its own children, yet some powerful men in the new hierarchy are already saying that it might have to do so: secular, democratic opponents of the former regime are denounced as counter-revolutionaries, most clergymen seem determined to turn Iran into an intolerant theocracy and a cultural backwater, and martyrdom for Islam is held up for the young as the highest achievement they should aim at.

Read the full article

The rebirth of Chilean cinema in exile, the April 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Explaining Iran

Edward Mortimer

April 1980, vol. 9, issue 2

An extraordinary exhilaration gripped the Iranian people as the revolution at last triumphed and the remnants of the imperial regime suddenly crumbled away. One returns to confront the irritation of a European intelligentsia which is at once alarmed by the possible consequences of the Iranian revolution and perplexed by the fact that it does not quite fit into any of the ideological pigeon-holes which Western thought had prepared for it; and one is expected to atone by taking responsibility for the events which follow it.

Read the full article

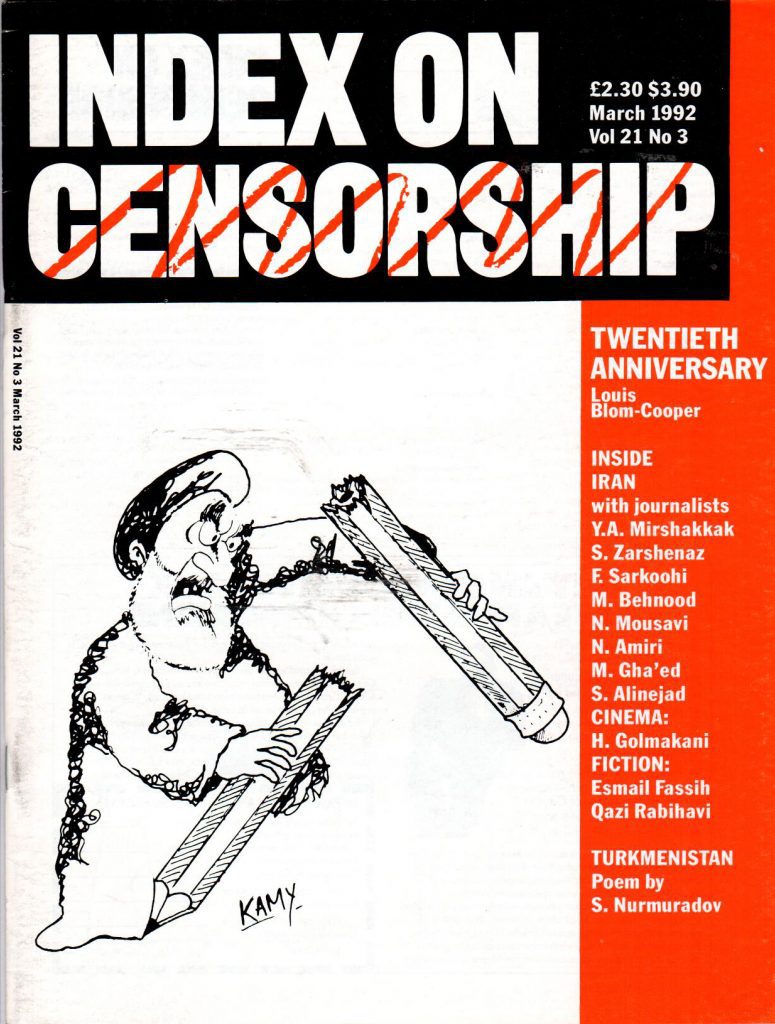

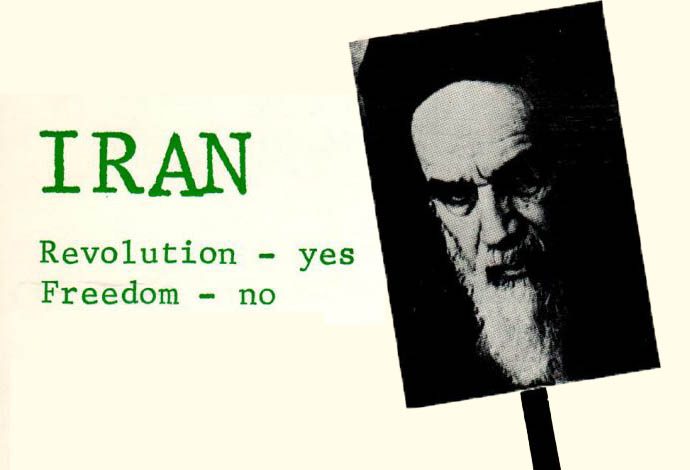

Iran: Revolution – yes, Freedom – no, the June 1981 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Iran since the shah

Leila Saeed

June 1981, vol. 10, issue 3

Concern for the restoration of social justice, for basic human rights, as well as national independence, provided the fundamental motive for the formidable mass movement which brought down the Pahlavi dynasty in February 1979. Iranians of different social backgrounds, ethnic and religious groups, of different creeds and ideologies came together in their revolt against the oppressive and arbitrary regime. And it was religion which provided the formal channels and the leadership by means of which the opposition expressed its demands and conducted its struggle.

Read the full article

Writers and Apartheid, the June 1983 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Islamic attack on Iranian culture

Amir Taheri

June 1983, vol. 12, issue 3

Book-burning did not become an Islamic tradition. On the contrary. The Bedouin’s enchantment in front of the written word soon prevailed over the Caliph’s ‘ impulsive outburst. Islam expanded and developed into an established religion with universal appeal, and became an accidental heir to the wisdom of the classical world which it later passed on to the West. In 1979, in the triumph of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, an echo of Omar was heard. In their hatred of the “corrupt” contemporary world, Iran’s mullahs, who had designed and led the revolution, tried to “return to the source” and recreate the early Islamic society as they imagined it. An important step in that direction was what the revolution’s Supreme Guide, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, described as “deculturisation”.

Read the full article

Samuel Beckett: Catastrophe, the January 1984 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Iran under the Party of God

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

February 1984, vol. 13, issue 1

Censorship was planned by the regime of the Islamic Republic even before the February 1979 revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic oligarchy to power. This particular kind of censorship may not be without precedent in history, but it must certainly be rare. There were attacks on coffee-houses, restaurants and other public places by men armed with clubs and stones; unveiled women were harassed; slogans of the opposition were cleaned from the walls; banks, cinemas and theatres were burned. None of this seemed to follow any specific plan, but nonetheless it just kept on happening. Men with angry faces, dressed in shabby clothes, would be seen lurking in corners; they would come out for a moment of sudden violence and then disappear again. An astute observer might have called those attacks wounds on the body of the revolution as it was in the process of taking shape, but not many people noticed, and consequently they saw this deranged behaviour simply as a sign of revolutionary anger and class hatred.

Read the full article

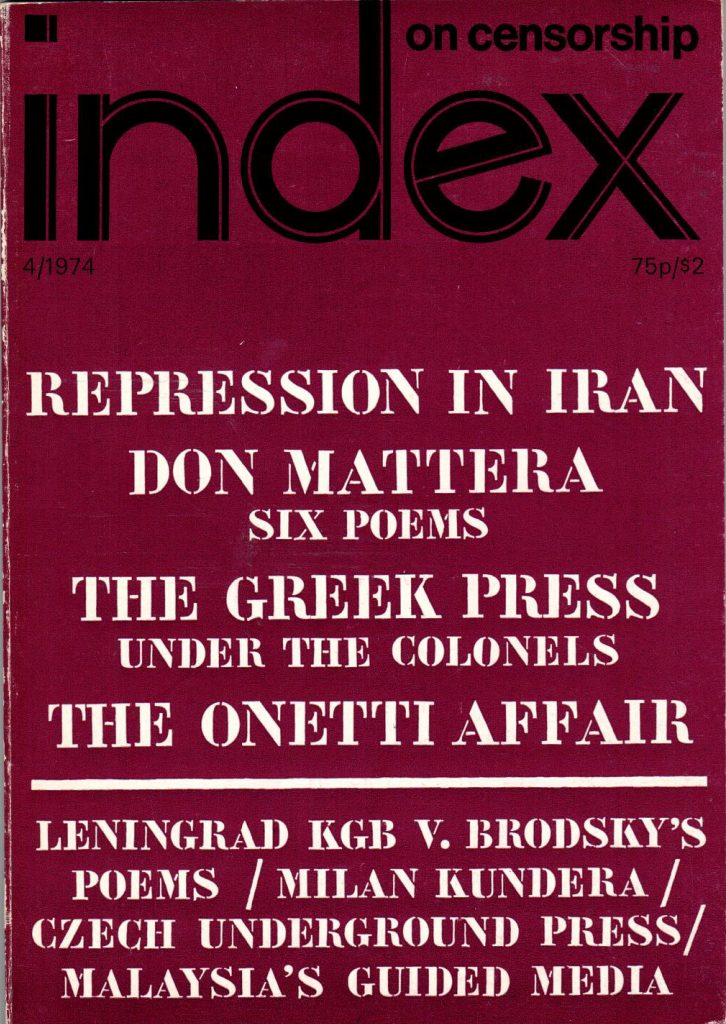

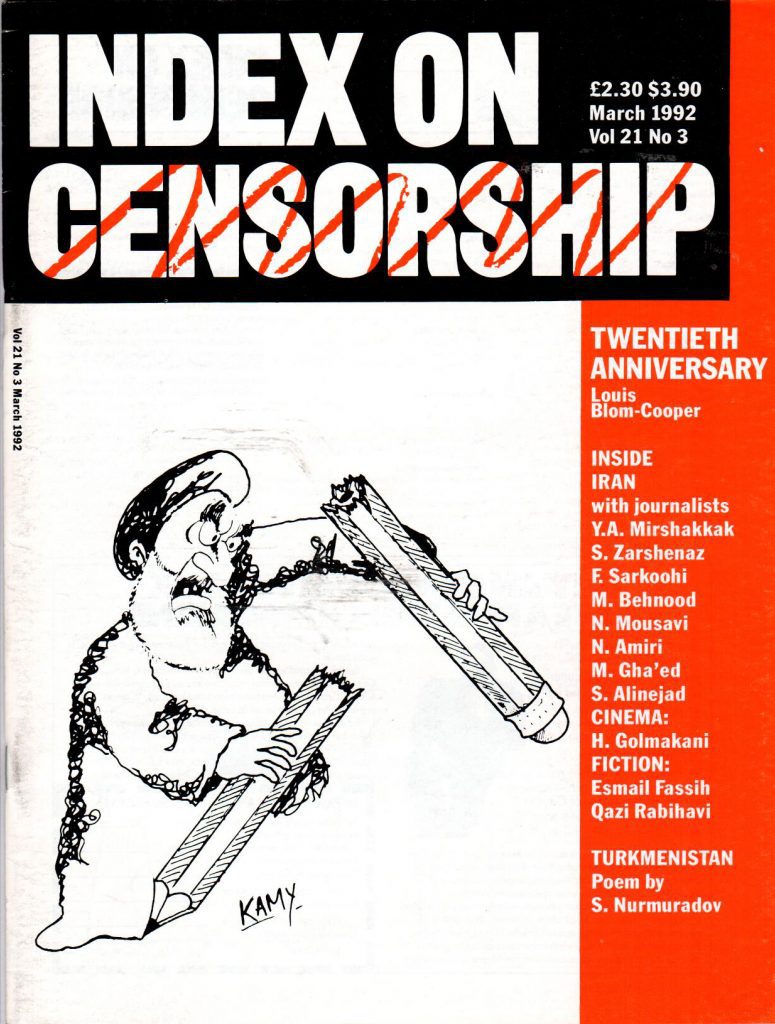

20th Anniversary: Freedom and responsibility, the March 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Inside Iran: A Special Survey

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

March 1992, vol. 21, issue 3

Index brings together opposing views on the nature of human rights, freedom of expression and democracy within the Islamic Republic of Iran. This unique confrontation, first presented on 14 December 1991 on the UK’s independent Channel 4 TV programme South, reveals the gulf that separates the ‘universal’ principles of the Western Christian/humanist tradition from the theocentric teachings of Islam on the same matters. Even within Iran, the battle between rival and opposing interpretations of Koranic teaching on these subjects reaches into the highest levels of government.

As the Iranian journalist Enayat Azadeh, intimately connected with the film, himself says, we are not talking about anything as simple as those who are for and those who are against the Revolution. Committed supporters of the Islamic state who, influenced by education and inclination, wish to incorporate Western liberal ideas into Islamic thinking on, for instance, freedom of expression in the media or the arts, find themselves at odds with the pure Islamists who will brook no interference with the integrity of Islam

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549892591542-afaf5ec8-5514-0″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]