As a child I used to dream about the day I would go to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. I’d watch the movie on repeat, always captivated by the moment when Charlie enters that room, the one with the marshmallow trees and the chocolate river. In other words, the room of childhood dreams. Flash forward to a year ago. My son was having a tantrum, refusing to leave the house (he was three, it happens). I was trying the normal tricks to calm and cajole him. Nothing was working. Eventually I told him about the Willy Wonka room. As if by magic he calmed instantly, put on his coat and we left.

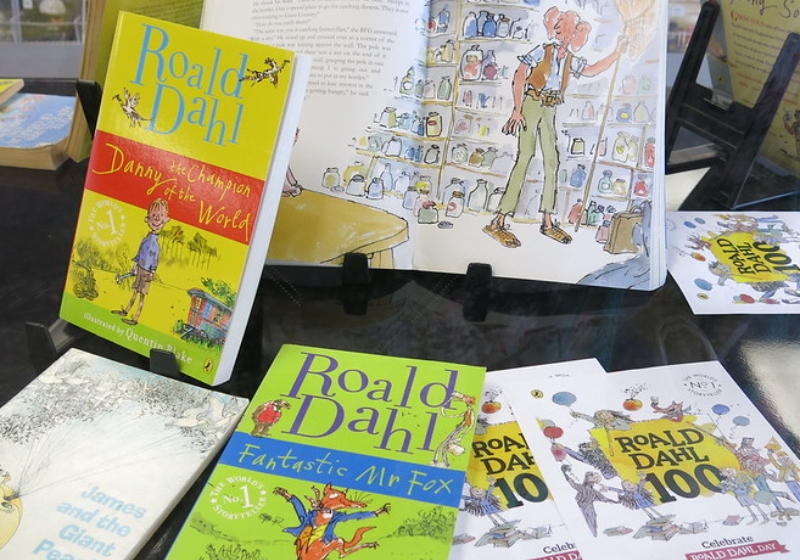

I didn’t mention Augustus Gloop in my retelling. If I had I might have missed out the fact he was “fat” because, well, I try to avoid that word in my house. I don’t want my son to grow up body conscious or to fat shame others. That is my prerogative as a parent; I can filter and rewrite as I see fit. It is not, though, the prerogative of the publishing house, or a streaming service. But that’s exactly the role they have given themselves. As was recently announced in The Daily Telegraph, Roald Dahl’s children’s books are being rewritten to remove language deemed offensive by the publisher Puffin. Sensitivity readers have been hired, their job to bring the books up to the 21st Century. So Augustus Gloop is now “enormous” not “fat” and, amongst other issues that I’ll get to shortly, I’m curious as to whether that is even any better?

Ditto references to “female” characters like Miss Trunchbull in Matilda, who has gone from a “most formidable female” to a now “most formidable woman”. Shouldn’t that be “person”? Or do we have to wait for the 2024 edition?

This sets a really bad precedent. I hate to be the cliché – work at Index on Censorship, talk about slippery slopes – but this really is a slippery slope. The library shelf that Dahl’s books sit on is full of works that teeter on the edge of PC. Take just one example, Judith Kerr’s beloved The Tiger Who Came to Tea. In this it’s Sophie’s mother who is at home looking after Sophie while it’s Sophie’s father who is at work, and it’s Sophie’s father who has the great idea to go out for sausages and chips (and presumably has all the capital to pay for it). Of course Daddy bloody saves the day! Shall we rewrite that?

I don’t like the traditional gender roles of Kerr’s book, nor do I like some of the language and descriptions in Dahl’s. But these books are products of our uncomfortable past and no amount of editing can change that past. Editing can, however, gloss over it as if it never happened, which is far more concerning. How are we supposed to understand who we are today if we don’t have the context of where we’ve come from? It even denies us our victories. “Look! Mummy and Daddy both work today!” I can tell my kids proudly if they question the dynamics in Kerr’s Tiger.

Another troubling aspect concerns author consent. In the journalism industry, once something has been published it’s considered bad practise to make any changes, certainly without the permission of the author. With Dahl, not only have words been changed, passages have been added. According to the Roald Dahl Story Company “it’s not unusual to review the language” during a new print run and any changes were “small and carefully considered”. Are these small? In The Witches, when it first introduces the witches as bald beneath their wigs a new line follows: “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.” That’s very well-meaning, it’s just that Dahl didn’t write that. I fear the power we are giving to publishers and estates to reword as they see fit. Ultimately in the wrong hands good intentions easily turn bad.

My final irritation is more personal. My son’s bookshelf is spilling over with stories, a glorious catalogue of old and new. I’m amazed by the number of fantastic children’s writers out there today and a little overwhelmed. Justification for the Dahl modifications seems to be along the lines of a commitment to diversity and inclusivity, something we can all get behind. If Puffin and Netflix are so committed to these values why don’t they instead invest in and support authors from other backgrounds? After all, Roald Dahl was a white male with an anti-Semitic track record. He’s hardly the poster boy of 2023.

As much as they have their problems, I like some of Dahl’s characters and plots both from a place of nostalgia and from a place of good story-telling. I look forward to the day when my son progresses from tales of golden tickets to giants outside windows (way too scary for now). But he shouldn’t need to watch Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on repeat like me because there are many other brilliant books out there, waiting to be turned into film. What we need is money channelled to new stories, not new, redacted versions of Matilda.

This article originally appeared in The Bookseller here.