The Online Safety Act could have been worse. When it was still a bill, it included a provision around content deemed “legal but harmful”, which would have required platforms to remove content that, while not illegal, might be considered socially or emotionally damaging. We campaigned against it, arguing that what is legal offline must remain legal online. We were successful – “legal but harmful” did not make the final cut.

Still, many troubling clauses did make their way into the Act. And three weeks ago, when age verification rules came into force, people across the UK began to see the true scope of the OSA, a vast piece of legislation which already is curtailing our online rights.

Setting aside the question of how effective some of these measures are (how easy is it, really, to age-gate when kids can just use VPNs, as we saw a few weeks back?), many of our concerns focus on privacy.

Privacy is essential to freedom of expression. If people feel they are being monitored, they change how they speak and behave. Of course, there is a balance. We use Freedom of Information requests to hold power to account, so that matters of national importance aren’t hidden behind closed doors. But that doesn’t mean all speech should be open to scrutiny. People need private space, online as well as off. It’s a basic right, and for good reason.

We’ve landed in a strange place in 2025. Never before in human history have we had such powerful tools to access people’s inner lives. But just because we can doesn’t mean we should. The OSA empowers regulators and platforms to use those tools, mostly in the name of child safety (with national security also a stated goal, albeit one that seems secondary), and that’s not good.

To be clear: I empathise with concerns around child safety. We all want an internet that is safer for children. But from every conversation I’ve had, and every piece of research I’ve seen, it won’t make much of a difference to the online experience of our children. There are too many loopholes and the only way to close them all is to further encroach on the privacy of us all. Even then there will still be get-arounds.

What does a less private internet look like? Just consider a few ways we use it: we send sensitive data, like bank details, ID documents and health records, to name just three. That data needs to be private. We talk online about our personal lives. In a tolerant, pluralistic society, this may seem unthreatening, but not everyone lives in such a society. Journalists speak to sources via apps offering end-to-end encryption of messages. Activists connect with essential networks on them too. At Index we use them all the time.

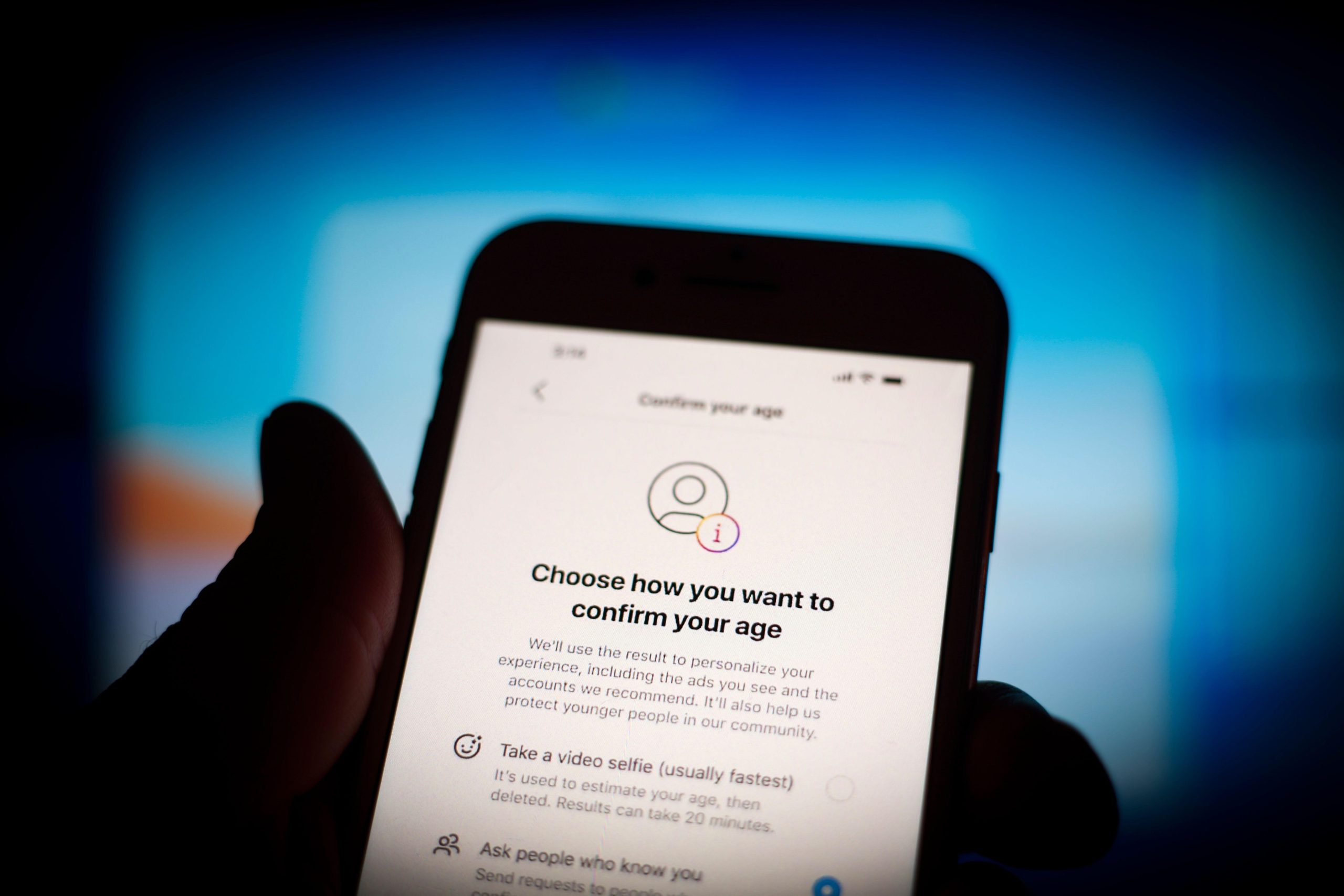

The OSA is already eroding privacy. Privacy is being compromised by the OSA’s age-gating requirement under Section 81, which mandates that regulated providers use age-verification measures to ensure children – defined as those under 18 – don’t encounter pornographic content.

This means major platforms like TikTok, X, Reddit, YouTube and others must comply. Several sites already have profiles of us, based on information we’re had to upload to register, and the tracking of our online habits and patterns. Now our profiles will grow bigger still, and with details like our passports and driving licences. Although the OSA says age verification information should not be stored we already know that tech is not infallible and this additional data could be extremely powerful in the wrong hands. We’ve seen enough major data breaches to know this isn’t a worse-case abstraction.

But it could get worse. Section 121 of the OSA gives Ofcom the power to require tech companies to use “accredited technology” to scan for child abuse or terrorism-related content, even in private messages. Under the OSA, technology is considered “accredited” if it has been approved by Ofcom, or a person designated by Ofcom, as meeting minimum standards of accuracy for detecting content related to terrorism or child abuse. These minimum standards are set by the Secretary of State. By allowing the government to mandate or endorse scanning technology – even for these serious crimes – the OSA risks creating a framework for routine, state-sanctioned surveillance, with the potential for misuse. Indeed, while the government made assurances that this wouldn’t undermine end-to-end encryption, the law itself includes no such protection. Instead, complying with these notices could require platforms to break encryption, either through backdoors or invasive client-side scanning. Ofcom has even flagged encryption itself as a risk factor. The message to tech companies is clear: break encryption to show you’re doing everything possible. If a company doesn’t, and harmful content still slips through, they could be fined up to 10% of their annual global revenue. They’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

Yes we want a safer internet for our children. I wish there were a magic bullet to eliminate harm online. This isn’t it. Instead, clauses within the OSA risk making everyone less safe online.

Sometimes we feel like a broken record here. But what choice do we have, when the attacks keep coming? And it’s not just the OSA. The Investigatory Powers Act, formerly dubbed the “Snooper’s Charter”, has also been used to demand backdoors into devices, as we saw with Apple earlier this year.

So, we’re grateful that WhatsApp recently renewed a grant to support our work defending encryption and our privacy rights. As always, our funders have no influence on our policy positions and we will continue to hold Meta (WhatsApp’s parent company) to account just as we do any other entity. What we share is a core belief: privacy is a right and should be protected. And at Index we work on a core principle: human rights are hard won and easily lost. Now is not the time to give up on them – it’s the time to double-down.