4 Apr 2018 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Portugal

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The photo that won Enric Vives-Rubio the 2017 Gazeta Award, one of the most prestigious awards in Portuguese journalism.

Despite having worked in Portugal’s small media industry for the past two decades, photojournalists Enric Vives-Rubio and Nuno Fox have never worked in the same newsroom. However, their careers share certain similarities, including poor working conditions, job loss and a reluctant turn of their backs to the profession.

Vives-Rubio got a job at the Portuguese daily Público in November 2005. “It was just the kind of newspaper I hoped I’d work for one day,” he told Mapping Media Freedom.

However, the conditions offered didn’t match Vives-Rubio’s hopes. Instead of proposing to hire him on a regular contract like most of its workers, Público offered to pay him through a “recibo verde”. These “green receipts” are a way for independent or freelance workers to charge companies for their services on an occasional basis, but the system is often abused by Portuguese companies to hire de facto full-time workers without offering them job security or the benefits that come with a full-time contract.

Employers get all the advantages of full-time staff — no obligation to grant job benefits and the possibility to lay off employees with no justification or severance pay due — while the worker is left with no job security and pays nearly twice as much tax as someone on a regular contract.

According to a study by the Union of Journalists, 33.4% of journalists working in Portuguese newsrooms are working without a contract. Although there isn’t a specific number, João Miguel Rodrigues, a photojournalist and a member of the Union of Journalists, says that “many are photojournalists”.

The offer made to Vives-Rubio by Público was hard to resist. “The offer was bad, but I couldn’t say no otherwise I’d be unemployed,” he explained. He was told when he was hired that the green receipt situation was “temporary” and that two months later — come the end of the financial year in 2006 — he would get a proper contract.

“Things didn’t turn out quite like that after all,” Vives-Rubio said.

During the first two years, he’d ask his superiors about his situation on a monthly basis. His insistence got him a contract — although not the one he was looking for — in which he would still work under the green receipt system on an annual basis. This, however, did not grant him any job benefits or job security beyond 365 days.

While all of his colleagues had a €3,000 annual stipend to spend on working material, Vives-Rubio had to pay for his own camera and lenses. He also missed out on food allowance, health insurance, sick days, parental leave and the additional two pay packets per year that full-time workers are entitled to by law.

The situation dragged on until June 2017 when he was called for a meeting with Público. They wanted him to work 15 days per month rather than 22 (a decrease of 32%), and for €1,000 instead of €1,750 (a decrease of 43%).

“They weren’t there to negotiate and were just looking for a way to get rid of a problem,” Vives-Rubio said. Leaving the room without a deal in hand, he resolved to work until the end of his contracted year on 23 July. During this time he was given less assignments while his colleagues were given more. Then, in June, his entrance card stopped working. Público had told a contracted worker who had been going in and out of the building for 12 years that he was barred from entering.

Since he was laid off, Vives-Rubio has received the Gazeta award, one of the most prestigious in Portuguese journalism. However, he doesn’t see a future for him in the media industry anymore. “Photojournalists are all slowly being laid off, so why knock on doors?” he asks. “I’ll keep on making journalism, but it will be for myself. As a photographer, I’ll have to reinvent myself.”

The experience of photojournalist Nuno Fox is similar to that of Vives-Rubio. Ever since he started his career in 2004, he has never had a full-time contract. He started his career at the daily Diário de Notícias before moving to the weekly Expresso, all under the green receipt regime.

“I was hired after there was a layoff in the newspaper and they needed to fill in some positions,” said Fox. He was given a €1,500 monthly salary. “This figure was verbally agreed; there’s no paper trail,” Fox said. “I was a part of the newsroom in every way except I wasn’t properly contracted.”

Fox also used his own camera and lenses too. In one of his last assignments for Expresso, he covered the funeral of Portuguese football legend Eusébio. “It was raining heavily but I had to do my work anyway,” he says. As a result, two of his lenses were damaged. “I thought the newspaper would pay for the damage but they told me it was none of their business. I had to pay €900 to fix one of them and I gave up on the other one because it would have cost me more than €1000 to repair it.”

In 2014, the Impresa media group, to which Expresso belongs, decided to create a pool of photojournalists that would work across all of its titles. Fox wasn’t included and was told his services were no longer needed. “I had no protection against this, so it was an easy choice for them,” he says.

The day after he was laid off, Fox wrote down a list of all publications he was interested in working for, picked up the phone and called their photo editors. “I knew things weren’t easy in journalism, so I decided to go beyond those phone calls,” he says. He also made calls to find work as a commercial photographer. “It was never my intention to go that way, I really believed in journalism, but I was left with no option.”

Three years on, most of Fox’s income now comes through commercial photography. At first, he felt uneasy about turning his back on photojournalism, but is now at peace with this reality. “It’s not that I lost my passion for the job, but I don’t identify with the mindset that values quantity over quality that brought us here.”

Rodrigues underlines that “photojournalists are the most affected by job instability” amongst Portuguese media workers. Those who work with images rather than words deemed less crucial for journalism. “In the eyes of many in newsrooms, photojournalists are looked down on as mere technicians.”

Photojournalists are among the “most versatile” elements in newsrooms and, with increasing pressures, aren’t given enough time to do their jobs properly, Rodrigues says. “When photojournalists are treated like this, the pride they take in their work vanishes and they lose their motivation.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1525097962341-ec9d666d-b1a7-9″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Jan 2017 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Portugal

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Although not exposed to the perils that press freedom encounters in places such as Turkey or Hungary, experts in Portugal tell Mapping Media Freedom that journalists in the country live under a “subliminal” type of pressure that can lead to the deterioration of their work and their fundamental rights as media workers.

Most of this pressure, they say, is caused by low wages and endemic job insecurity.

“I can’t say that there’s a threat to freedom of the press such as the interference of political authorities or in the sense that a certain information is silenced, the risk of an attack like that happening is small,” says Carla Baptista, a professor at the communication sciences department of FCSH-UNL. “But there are factors that weaken journalism and journalists and which undermine their capacity to resist if and when those attacks strike.”

According to a study conducted between 2007 and 2014 by Observatório da Comunicação, more than 1,200 journalists — about 20% of the total of media workers — have either lost or left their jobs. This tendency has only but grown ever since, with layoffs taking place in newspapers such as Diário Económico (which later shutdown its paper and online edition at different stages in the early in 2016), Diário de Notícias, i, and Sol. Besides, all in 2016, newspapers Público and Expresso, and magazines Visão and Sábado, put forth voluntary redundancy programmes for journalists and other professionals.

In another study by João Miranda, a journalism researcher at Universidade de Coimbra, that was answered by 806 journalists, 56.3% earned less than €1,000 per month and 14.8% declared they were paid below minimum wage (€505) or nothing at all.

“The fact that so many journalists have no job security affects the way they regard their own activity. In some ways, this restricts the conditions under which freedom of the press exists in Portugal,” João Miranda tells Index.

Sofia Branco, president of the Portuguese Union of Journalists and a journalist at Lusa news agency, seconds his words. “This is not an average job, it has very concrete responsibilities. It’s hard to demand independence and autonomy from a journalist when he or she is working under such circumstances,” she adds.

Is pressure under-perceived?

In Miranda’s research, a total of 23.8% journalists said they felt pressured by their outlet’s board of directors and 26.2% said they felt the same coming from their editorial superiors. However, when asked whether this pressure was exerted with a commercial motivation or rather for political gain of third agents, Miranda recognised that his data “doesn’t go deep enough to assess that.”

“To be honest I think those numbers are too low”, Branco said of the approximately one quarter of journalists who complained of being pressured. “A lot of people are under pressure but don’t realise it. It’s a matter of perception. The pressure does exist and is there constantly, even it most of the times it’s just at a subliminal level.”

Although sensible to the challenges most Portuguese journalists deal with in their daily lives, Carla Baptista argues that “journalists also have to take responsibility”.

For this Lisbon-based researcher, the Portuguese media have failed to investigate the country’s authorities, to set the agenda, and also to serve their audience. “There are asymmetries in the way our society is reflected in the media. They are distanced from the problems of those who they should be talking to: young people, women, families, voters,” Baptista said.

In her view, the average Portuguese journalist looks as though he or she is “a factory worker in the assembly line who is feeding a stream of ready made news like the 19th century coalman would feed an industrial oven.”

First journalists’ congress in 19 years to be held in January

It is to look inside all of the above mentioned problems and to seek their solutions that the Portuguese Union of Journalists, alongside two other non-union journalistic associations, will hold the 4th Conference of Journalists from January 12th to the 15th — a much anticipated event since it last took place, in 1998. Its first edition dates back to 1982 and the second happened in 1986. In this year’s edition, a total of seven panels will discuss topics like the ethics of journalism, the working conditions of media professionals and the economical viability of the news media.

“The fact that the last time we all sat down to discuss our work as 19 years ago is unbelievable,” Branco points out. “This time, we can’t close the doors without having reached conclusions both to ourselves, to the the institutions we work for and to the government, too.”

Baptista feels less optimistic. “My fear is that this conference will reflect the anemia of most Portuguese journalists,” she says. “I think 2017 will be a very bad year for journalism in Portugal.”

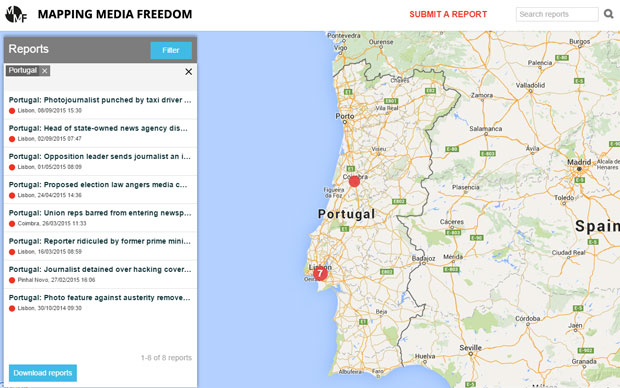

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483954255579-f41de8e9-b0bd-8″ taxonomies=”7679″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Feb 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Portugal

If there was any room left for doubt, the closing months of 2015 were enough to prove that Portuguese journalism is facing a serious challenge from which it probably won’t emerge the same. From October to December 2015, four media groups announced that they preparing to lay off workers, including journalists.

These recent cuts are a continuation of the long-term trend: between 2007 and 2014, more than 1,200 journalists — about 20 per cent of the total number of media professionals — have lost their jobs in Portugal, according to a study by Observatório da Comunicação.

The latest round of attrition began in November 2015 when the largest Portuguese media conglomerate Impresa announced it would terminate the contracts of 60 people, 20 of whom worked for the television channel SIC.

In December, the management of Público, a newspaper, announced that, due to a predicted €3 million in losses for the year of 2015, it was launching a voluntary redundancy programme for journalists and other professionals. The announcement came with a deadline: 6 January would be the last day for workers to reach a settlement with the managers. Index on Censorship has learned from an employee at the paper that 24 people have reached a deal and are set to leave the newspaper.

Despite the voluntary redundancies and cuts that included the folding of 2, the newspaper’s Sunday magazine, the company said that more layoffs may be required to reach its cost reduction targets. Público’s management has not yet to announced if more staff cuts will be made.

Público is owned by SonaeCom, a branch of Sonae, one of the biggest companies in Portugal. In 2014, Sonae had a turnover of €4.9 billion.

Within days, Diário Económico, Portugal’s leading business newspaper, revealed that due to a €30 million debt, fiscal authorities appropriated the title’s revenues until it solved its financial problems. In a statement to the newspaper Expresso, the editor-in-chief of Diário Económico, Raúl Vaz, admitted that the “situation has become much worse and more complicated, not to say dramatic”. The 26-year-old title may be forced to close, leaving 160 unemployed.

The most unusual of all dismissals happened at the Newshold media group, owned by Angolan banker and businessman Álvaro Sobrinho. On 30 November, employees at the Newshold newspapers Sol and i were told that the company was going to withdraw its investment in the two titles after claiming losses of €4.4 million and €3.8 million, respectively. The papers wouldn’t be folded under the Newshold plan, which would transfer them to a new management entity but axe two-thirds of the staff.

In the Newshold case, Mário Ramires, then CEO of the company, called a newsroom meeting at which he requested that employees staying with the papers sign new contracts that included smaller salaries. Crucially the new contracts would offer less legal compensation in the event of another round of layoffs, according to the recording of the meeting.

Ramires then asked the nearly 120 people who were losing their jobs to give up legal compensation that the company is obliged to pay under Portuguese law. He told the departing staffers that if they didn’t accept this, they would be putting the future of the papers and their colleagues’ jobs in jeopardy.

“All companies die today, they’ve been broke a long time ago. Nobody is entitled to anything because the companies have no money,” Ramires is reported to have said to his employees. “Whoever feels like crying, complaining that this is too tough and stuff like that, it’s best for them go home this second.”

The two-hour meeting was filmed with the consent of the employees. Two days later, following a visit by representatives of the Journalists Union to the news offices of i and Sol, Ramires ordered the audio of the meeting to be published on the websites of both titles. In it, Ramires, who is now editor-in-chief of the two newspapers, mentioned his wife and two sons, who he brought to the meeting. “I’m not giving up, and even if everybody jumps boat I will not give up,” he said. “And that’s why I brought my children here.”

The Journalists Union issued a statement appealing to all the Newshold journalist to “not sign, for the time being, any documents” presented to them. However, as one employee involved in the process who asked to not be named told Index, all the journalists signed documents in which they absolved the company a legal requirement to open a bank account where severance payments would be set aside. Ramires said the company could not afford to open the account at the time and assured the exiting employees that they would receive their money in January 2016, which occurred for most of the journalists. Some of the former employees are involved in disputes over vacation time and have not yet settled with the company.

Ana Luísa Rodrigues is the acting president of the Portuguese Union of Journalists and a journalist for RTP, Portugal’s public television channel. In an interview with Mapping Media Freedom correspondent João de Almeida Dias, Rodrigues said she believes that the shortage of journalists working in newsrooms — a consequence of several collective layoffs that took place in the past five years — has a negative effect democracy and press freedom in the country. Another effect has been “numbing” of media workers that avoid raising questions in fear of losing their jobs.

Index: Do you feel that the quality of the journalism that is made in Portugal has decreased as a consequence of fewer people working in the media?

Rodrigues: I think it’s there for everyone to see, it’s not just us journalists who notice it. Consumers feel that too. For example, it’s now commonplace for two newspapers to have the exact same article. That often happens in Jornal de Notícias and Diário de Notícias [two newspapers owned by the Global Media group], where they publish the same content written by the same journalist. So here’s two newspapers, which are in theory made for two different audiences, publishing the same article. And this happens with topics of the utmost importance, sometimes they have the same front page headline. This is not an exception, it has become the rule. We’re now beginning to accept this as normal. But why should it be normal?

Index: Who is to blame for the layoffs?

Rodrigues: I’m not in a position to pass judgment, but it’s important to point out a few things. First, this is an administrative decision which is made by people who think that running a media business is the same as running a sausage factory. The level of social responsibility is very low. Then, this is possible because of the complacency that some editors, who think that there is no alternative. But if we think that two different newspapers can publish the exact same article except for a tiny change of words in the headline, then one day we may start thinking that journalists aren’t needed anymore. If we accept this now, then we may start accepting many other things in the near future. And that leads me to my last point, which is the journalists. Considering the lack of job security in journalism and the high unemployment figures in the media, not a lot of people can walk out the door from a newspaper where they don’t enjoy working. And this has numbed a lot of media workers. The things that outraged us 20 years, 10 years, five years ago, seem normal to us, now.

Index: You often say that the less employed journalists there are, the more endangered democracy is. How so?

Rodrigues: If we have fewer people in our newsrooms, then we have fewer people to cover many topics that are important to our society. And those who still are in the newsrooms don’t have much time to do their job, because while there are fewer people in newsrooms, there is more work to do compare to a few years ago when there wasn’t cable television news channels or the internet. A journalist needs time to investigate phenomena and subjects that are surreptitious. So this leads to the impoverishment of a fundamental tool for the rule of law. Newsrooms have fewer eyes, fewer hands and less thinking heads which can reflect on our times.

Index: Do you believe that the state of affairs in media businesses also affects press freedom?

Rodrigues: Yes, in the sense that the work of journalists has a smaller margin. We are just like everybody else, we have bills to pay and children to raise. And when you live in an environment where there are mass layoffs or where journalists are compelled into leaving their jobs through contractual agreements, it’s obvious that the exercise of the amount of freedom every media worker must have can be compromised. I can tell you that the current environment does not favour press freedom. It takes us to situations where journalists apply self-censorship in a way that they don’t go as far as they should to contest editorial options made by those above them. Apart from that, the pressure to publish something or to do otherwise is not a new thing. But what we have now is an environment which can augment that.

Index: Both Sábado and Correio da Manhã, owned by the Cofina media group, received a legal injunction that prohibits them from writing about the judicial case of José Sócrates, a former prime minister who’s now a suspect of tax evasion, money laundering and corruption. Do you think that was a fair decision?

Rodrigues: The Union of Journalists have already stated that cutting an article short before it’s even written or published is an attack on press freedom that should be fought against and denounced. This prohibition by default makes absolutely no sense. But having said that, the act of a journalist becoming an assistant to a case with the sole purpose of writing about is something that doesn’t dignify journalism. But it’s still very clear that there is still no reason for a court to prohibit the press from publishing something that hasn’t even seen the light of day yet.

Index: Does the ownership of Portuguese media titles by Angolan investors worry you?

Rodrigues: It’s worrisome in many ways. It’s clear that there’s a certain mentality that makes no differentiation between running a media company, which means you have a higher degree of social responsibility to fulfil, and any other type of company. That’s a problem. Another problem is when one invests in a newspaper and at the same time behaves in a manner that is not friendly to the values of freedom. But I have to stress that this is not exclusive to those cases [of Angolan investors]. It’s important to understand that the concentration of media ownership is a worrisome reality which has been growing lately.

Index: Do you think it’s time for the government to begin a state subsidy that goes into financing newspapers, news channels or news radio stations?

Rodrigues: I think this shouldn’t be a taboo. It should be put on the table alongside other options. What I can tell you is that RTP and RDP (public television and radio) are financed with public money and I don’t think that anyone can honestly say that they’re more favourable to the government than the other media outlets. Besides, if you watch a Portuguese movie or go to the theatre, those productions will most likely have public funds, and that doesn’t mean that they’re acting nice towards the government. The ghost of the government’s involvement in journalism is something that should be discussed. We have to be honest about it. Why should we regard private investment as bona fide and think otherwise when it comes to public funding. This is something that we have to talk about. We can’t afford not to do that.

This article was originally posted at Index on Censorship

22 Oct 2015 | Angola, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Portugal

It all became perfectly clear in Miguel’s head when a high-ranking editor from his newspaper eagerly approached him one day with a story idea. It was August 2012, and the Angolan presidential elections were scheduled for the 31st.

“You’re going to write an article that will prove once and for all to the Portuguese audience that Angola is a true democracy and not dictatorship. We’ll show that it is the Portuguese who are the fascists here, not the Angolan,” the editor told him.

The assignment came as no surprise to Miguel, who was aware of the rumours that the cash-strapped newspaper he works for is one of the many Portuguese media outlets that have received cash infusions funded by Angolan investors. These investments come from individuals connected to Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos, the man who enriched himself and his country’s tight-knit elite throughout his 36 years of power. While rich in resources — Angola figures among the world’s top producers of oil and diamonds — the country’s profits benefit very few. The most shocking example of that is the fact that this former Portuguese colony has the world’s highest mortality rate for infants and for children under the age of five.

Eventually, after informing his editor that he didn’t share the opinion that “Angola is a true democracy”, Miguel acquiesced and wrote the article on the condition that his byline would not appear.

Later that month, on 31 August 2012, dos Santos won the election with a controversial 71.84% of the votes.

“After that, I imposed on myself a kind of conscious negligence on everything relating to Angola. I stopped thinking about it, not just in order to keep my job, but also for mentality’s sake,” Miguel admits.

Ownership of Portuguese media outlets by Angolan oligarchs is a way for the dos Santos regime to hide the country’s negative side while promoting it before a foreign audience, experts say.

“They know better than anyone that the media can help them create the illusion that Angola is a good example when it comes to politics, the economy or even human rights,” says Portuguese MEP Ana Gomes, a member of the European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Human Rights and a close follower of the Angolan situation. “It grants good publicity and an idea of respectability to Angolan personalities who got all their money by stealing assets of the Angola state.”

Francisco Louçã, a former leader of the Portuguese Left Block political party and co-author of the book The Angolans Who Own Portugal, told Index on Censorship that “by owning strategic positions of the Portuguese media, these businessmen and businesswomen who are very close to the Angolan regime can manage and condition the information that reaches Portugal, which, from their perspective, is the perfect gateway for other European markets”.

It’s hard to find a media title in Portugal that isn’t owned in some way or another by Angolan oligarchs — and although Portugal has yet to see the effects of media transparency legislation that will make it mandatory for newspapers to reveal their shareholders beginning on 27 October, many news reports dating back to 2008 show that Angolan money is being invested in the Portuguese media.

In March 2014, António Mosquito, an Angolan businessman with close ties to the president, purchased a 27.5% stake in Controlinvest media group — including Diário de Notícias, the country’s oldest newspaper, and Jornal de Notícias, the second-most read. A few months after this deal, 160 workers were laid-off, including 64 journalists.

Then there’s Newshold, a media group owned by Angolan banker and businessman Álvaro Sobrinho. After buying the weekly Sol in 2008, Newshold announced the acquisition of the daily i in 2014. Newshold is also a shareholder in the two largest national media empires: 1.9% in Cofina, which includes Portugal’s highest circulation newspaper, Correio da Manhã; and 3.2% of Impresa, owner of television powerhouse SIC and the prestigious weekly Expresso.

In 2012, Newshold was also a frontrunner for the concession of RTP, the Portuguese public television network, after the government announced that it was willing to put it into the hands of private owners — a sale that was later dropped.

Then there is the case of Isabel do Santos, daughter of the Angolan president and Africa’s richest woman. Much of her $3.1 billion (£2.07 billion) net worth has been facilitated by her father’s decisions, which led to Forbes to dubbing her “daddy’s girl”. Not long after that piece was published, Isabel dos Santos bought the rights to produce a Portuguese-language version of Forbes which will be sold in Portugal and in Portuguese-speaking African countries.

Although Isabel dos Santos has no reported ownership of a Portuguese media outlet, she does co-own NOS, Portugal’s leading cable television company, in a joint-venture with the Portuguese telecom mogul Sonaecom — which is also the owner of the daily Público.

“Portugal is a vanity fair for the so-called Angolan elite,” says Angolan investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais, winner of the 2015 Index Journalism award for his work uncovering corruption in his country.

Whether they are the recipients of direct investments or not, all newspapers in Portugal are dependent on money from Angola’s elite in the form of advertising. With holdings in Portugal’s real estate, telecoms, construction and banking industries, Angolan investors can potentially influence coverage through contracts for ad space.

It isn’t always clear how the Angolan money is invested in Portugal’s media. For example, in the case of i, a newspaper that has struggled with financial issues, a February 2012 purchase of a 70% stake by printing-house owner Manuel Cruz was completed behind a reluctance to reveal the identity of the investors. “It’s a deal that is done through a foreign group, of which I’m a shareholder representative in Portugal,” Cruz was quoted as saying at the time.

However, inside the newsroom, journalists became alert to the possibility that that investment had roots in the Angolan oligarchy. “It became known through rumours, which were later proved to be true,” says António Rodrigues, a former editor of i’s foreign news desk. “It got pretty obvious even without an official confirmation. It’s impossible for the owner of a printing house to be able to afford to suddenly buy an unprofitable newspaper during an economic crisis. There had to be someone from Angola behind him.”

Rodrigues was right. But this was only to be fully brought to light in September 2014 when i and Sol moved into the same building.

In the meantime, while journalists were left to speculate on who their mysterious bosses were, news regarding Angola became a sensitive topic. “One had to be more careful and it was policy to ask the editors-in-chief for permission to publish anything related to Angola,” Rodrigues said.

After seven months working under the new owners, Rodrigues was laid off and the foreign news section was left without a permanent editor — such responsibilities were transferred to the masthead. This led to a gradual, yet steady loss of importance of the foreign news section in the paper. It didn’t take long until negative news concerning Angola nearly disappeared from i, Rodrigues said.

Other Portuguese news outlets appear to have limited their coverage of Angola. The ongoing hunger strike by Luaty Beirão — an Angolan-Portuguese rapper who began protesting on 21 September after being accused, along with 14 other activists, of preparing “crimes against [Angola’s] state security” — has been met with reluctance by some newspapers. i and Jornal de Notícias are yet to give more space to the subject than a brief item. And while it did write about new business opportunities for Isabel dos Santos, Diário de Notícias devoted only a little more than one column to the hunger strike when a demonstration for Beirão’s freedom took place in Lisbon to mark the 25th day of his protest.

On 27 October, Portugal will implement a media transparency law that will make it mandatory for newspapers to divulge their list of shareholders — TV and radio stations already follow this procedure. Until recently, similar drafts have been voted down by the centre-right governing coalition.

“Resistance by the media owners to laws of this kind is very high and some parties respect this clearly. The Angola regime is a sacred cow to some of them,” says Louçã.

“Finally we have such a law that will bring some light to this very dark issue. And I’m sure that if we follow the money trail, we’ll always find our way to very important personalities of the Angolan regime with high stakes in the Portuguese economy,” says Gomes.

However, Marques de Morais, a connoisseur of the ways of the Angolan oligarchy, is more skeptical of the results of this new law.

“If the regime of José Eduardo dos Santos has shown an ability to do something, it’s to hide their footsteps. There is always a way for them.”

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 21 October 2015

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|