This account of censorship by F el-Manssoury, published in Index on Censorship magazine in 1981 in Libya is based on first-hand knowledge of the early years of President Gaddafi’s regime

As front-line soldiers, we were required to be on duty day and night, constantly alert and on our guard, because the enemy confronting us was vicious and wily. Our instructions were to strike back vigorously, taking our cue from our revolutionary leader; and so we translators at the Libyan Information Ministry in Tripoli were made ready to brandish our pens and mount the counter-attack at a moment’s notice. We were ordered to stay at our desks after working-hours — often until late at night. This was called in Libyan Newspeak at-tataoialijbari, ‘compulsory volunteering’. We were not paid for the overtime.

One spring day in 1973, Colonel Moamer Gaddafi announced to the world the details of his Third International Theory designed to replace both decadent capitalism *and Godless Marxism. The announcement came during an international symposium to which he had invited’ delegations — mostly young people out for a holiday — from many countries. His five-hourlong speech was televised live, ending at about 10 p.m. And it was at that hour that we, front-line soldiers of the revolution, received our orders to go on the attack. The enemy, it seems, had cast doubts on the Islamic roots of the Libyan Cultural Revolution and our instructions were to draft cables in Arabic, English and French to the effect that the Cultural Revolution derived its credo and moral inspiration from no other source but the Holy Qu’ran. These cables were to be sent to newspapers all over the world. The ministry became a beehive of activity as the text was first drafted in Arabic, and then the English version was entrusted to the star translator at the ministry, a young Egyptian in an advanced stage of arthritis. By 2 a.m., the cables had been sent to some 80 newspapers in countries ranging from Afghanistan and Australia to Zaire.

Only then was it discovered that by inserting one negative too many — Arabic English! — the translator had actually said that the revolution derived its credo from anything but the Qu’ran. As it turned out, this minor lapse went practically unnoticed.

Many of the papers to whom the cable was sent had folded years before — the directory from which the list was compiled being hopelessly out of date.

Dangerous books

It was as part of his cultural revolution that Colonel Gaddafi — addressed officially in Libya as al-akh al-aqeed (‘Brother Colonel’) — instructed his Information Minister, a former schoolteacher who had done time in prison for slapping the face of a provincial governor — to cleanse the country of all ‘dangerous books’. The Colonel was not very specific about his definition of a dangerous book but he did speak out vehemently against JeanPaul Sartre. A task force of men from the Ministry was instantly dispatched to crack down on bookshops and public libraries throughout the country. All bookshops and libraries were closed to the public for a few days while the censors went through stacks of printed matter. Their task was not without its hardships, however. For one thing, Libya had a relatively large community of non-Arab foreigners — mostly connected with the oil companies — which meant that some of the bookshops sold English, French, German and Italian books.

Most of the censors were ignorant of foreign languages; quite a few had never read a book even in their mother tongue. At any rate, no book written in a foreign language could really constitute a menace to the morals of the Libyan people who enjoyed a high ratio of illiteracy, and certainly Sartre could boast of few devotees in Gaddafi’s desert republic.

The censors still went through the motions of book-sifting, despite the fact that their brief was very vague. They had been instructed to confiscate and destroy any book considered to be derogatory to Islam or the Arabs, but since that was unlikely to be obvious from the title, a judgment that a certain book was not fit for circulation in Libya could only be arrived at after careful perusal of the book itself. This, clearly, was beyond the intellectual capacity of the ceasors, and so they confiscated, quite arbitrarily, a few books at random before allowing the bookshop or library to re-open.

Long after the men from the ministry had left, there was still prominently displayed in one of translation of a book by S. Y. Agnon. If the censorship committee had been able to decipher the publisher’s note on the back cover, it would have been shocked to learn that Agnon — who had just won the Nobel Prize — was an Israeli, and this would have been reason enough to send the bookshop owner to prison.

By and large, the foreign bookshops escaped relatively lightly, but their owners were so frightened that they became extra careful when ordering a new stock. This extra care did not always help them in weeding out undesirable books, for they were not much superior intellectually to the censors who had invaded their shelves.

Arabic bookshops were naturally subjected to a greater degree of scrutiny, Gaddafi being more explicit about the kind of book to be granted free circulation in Libya To be on the safe side, owners began to stock their bookshops mainly with Arabic classics written many centuries ago.

When it became known in the Arab world what kind of book the Colonel approved of — one can’t say Nvhat he liked reading’, because he does not read books — a few writers, mainly Egyptian, began to write books that were custom-made for Libya. Thus, an Egyptian writer who had begun his career as a free-thinker and existentialist, now declared that he had seen the light of Islam at last and celebrated his dramatic conversion to the true faith by writing a dozen books on the subject. Soon, he was practically the only contemporary Arab author whose books were sold in Libya.

Colonel Gaddafi, as the self-styled disciple and heir to Gamal Abdel Nasser, had laid claim to the Nasserist organisations in Lebanon after his hero’s death. He thus subsidised a daily newspaper and a weekly magazine. These Libyan-subsidised Lebanese papers became virtually the only Arabic-language periodicals on sale in Libya, apart from the Libyan press itself. As for the foreign press, it was generally banned, although when Time magazine chose the Colonel as the subject of its cover-story in 1973, he countermanded the decision of his censorship department by allowing the magazine free circulation — for that edition only. He had approved of the article.

No independent press

While the Libyan people were jealously screened from outside influences and hardly any foreign periodical allowed circulation inside the country, a selection of the leading periodicals of both Eastern and Western blocs was received at the Ministry of Information. There the front-line soldiers of the revolution made a digest of their most important contents for the benefit of the members of the Revolutionary Council — the highest authority in the land — as well as the cabinet. This daily digest — the Bulletin — was the Ministry’s proudest achievement. It was printed on roneo in an edition of about two dozen copies and classified as secret.

When an English Sunday paper began to serialise ‘The Hilton Assignment’, a book by Patrick Seale which purported to relate the plan of Omar Shalhi, an opponent of Gaddafi living in exile, to lead a group of European mercenaries in a landing on the Libyan coast in a bid to overthrow the Colonel, the number of copies of the translation was to be even smaller than that of the daily bulletin; Gaddafi didn’t want too many top people to know about the matter.

In that same fateful spring of 1973, Brother Colonel went on the air to exhort the Libyan masses to take over both the radio and television stations which were, in his view, not revolutionary enough. Within hours, lorries were commandeered to carry indigent Libyans to the offending addresses in order that they put things right. However, listeners and viewers who tuned in that evening hardly noticed any perceptible change in preand post-Cultural Revolution programmes. But the two stations were, it was maintained, firmly in the hands of the masses.

The Libyan press was another matter. When Gaddafi took over in September 1969, he closed all the papers which he considered royalist. Finding, however, that there were no longer any journalists around who were both qualified and revolutionary, Iraq’s academic death toll No single incident exemplifies the state of academic freedom within Iraq more than the assassination in South Yemen of Professor Tawfic Rushdi on 2 June 1979. He was a philosophy lecturer at the University of Aden. His assassins were officials at the Iraqi Embassy there (Guardian 5.6.1979). Though a critic of the Iraqi regime. Professor Rushdi was by no means a political activist. Murdering him was the Ba’athist way of reminding the tens of thousands of Iraqi academics abroad that being an exile provides no safety from physical liquidation, for fear of which they left their homeland. During the past month alone some 150 lecturers at various universities in Iraq were sacked: yet another signal that Saddam Hussain Takriti’s regime has reached an advanced stage in implementing a crash five-year plan to Ba’athisise completely all educational institutions in Iraq. In fact, of the known 4000 people executed or tortured to death since 1968, nearly one quarter were from the academic world. Middle East Currents 30 June 1981 he tried to woo back the so-called royalists. But these, rightly suspecting the Colonel of requiring their services only as long as it would take him to find people who were more to his liking, would not cooperate. Eventually, Gaddafi succeeded in starting his own revolutionary press. It was so revolutionary that it carried little news; instead, it highlighted exhortations for greater revolutionary fervour and self-sacrifice, attacks on the reactionaries and the imperialists — and interminable telegrams of support for the Colonel from various segments of the population. There are no independent papers in the country — all are owned by the state. There are no book-publishers either, for again it is the state alone which publishes books.

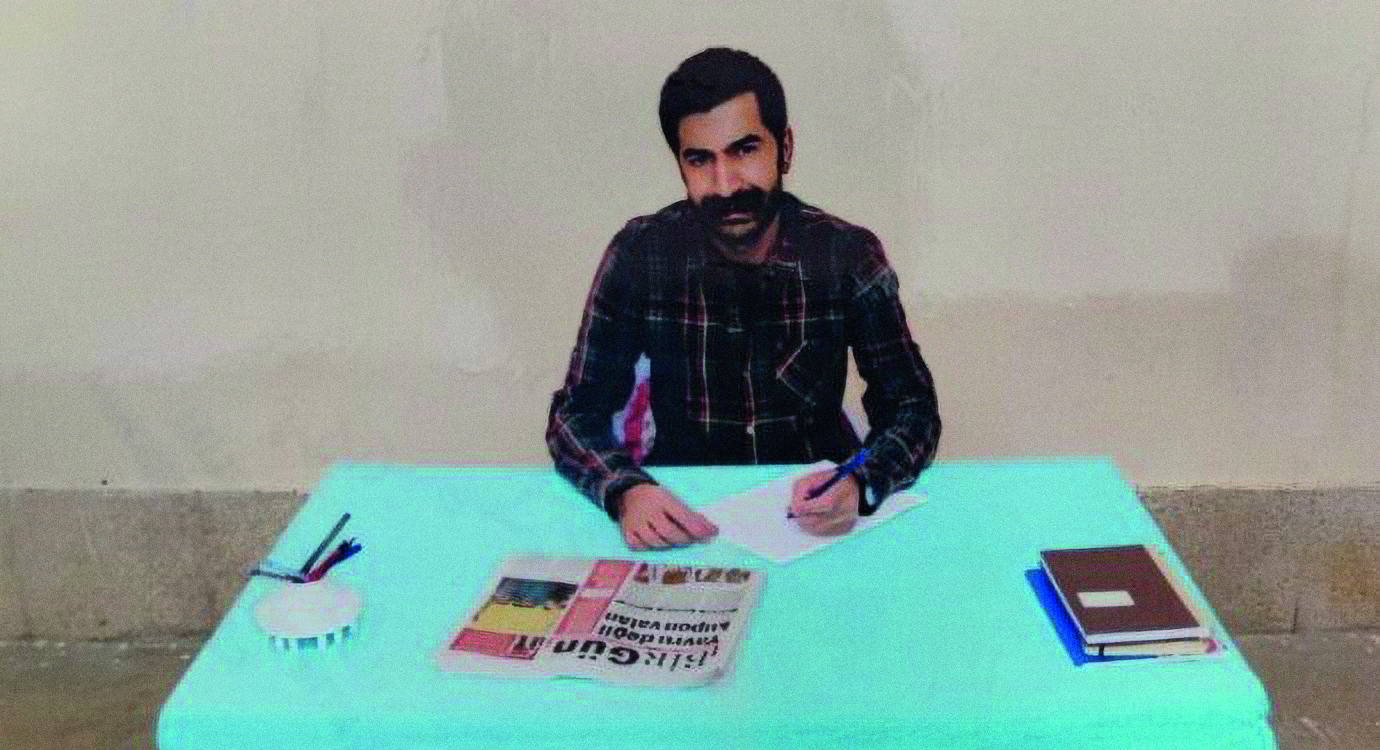

Everything is geared to propagate the Colonel’s ideas and theories, for his ambition is to create a new Libya — in his own image. The paradox in the Colonel’s dream of resurrecting ancient Arab glory Is inherent in his own ignorance of the Arab legacy in literature, philosophy and the arts. Indeed, if great Arab thinkers of the past such as Ibn-Rushd (Averroes) and Ibn-Khaldun, were alive today, their books too would be banned in Libya. F. eHVIanssoury F. el-Manssoury is a Libyan journalist now living in exile in Spain.