Nasrin to remain in India

Novelist Taslima Nasrin, in exile in India after her writings led to threats in her native Bangladesh, has had her visa extended by the Indian government.

Novelist Taslima Nasrin, in exile in India after her writings led to threats in her native Bangladesh, has had her visa extended by the Indian government.

On the Saturday before Christmas 2004, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in Britain’s East Midlands was in a state of siege. Children who had come with their parents for a pantomime were bewildered at the sight of 400 enraged protestors threatening to storm the theatre.

Later that afternoon, the mob attacked the building, shattered glass, destroyed backstage equipment and injured several police officers.

The protesters were Sikhs, mainly men. Their ire was directed at the play Behzti (Dishonour) by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti, who is herself a Sikh. And so we return to the ongoing saga of intolerance and free expression; censorship and multiculturalism.

Nearly two decades ago, in another UK city, Bradford, Muslim men burned copies of Salman Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses. Iran’s spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini had declared a fatwa against Rushdie and British Muslims, many of them from India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, wanted the novel banned in the UK.

I was in Bombay at that time; on Mohammed Ali Road, I saw angry Muslim protesters trying to march towards the British Council a few miles away, which they wanted to burn down. They fought pitched battles with the city’s police, who wanted to stop them. They hurled glass bottles filled with acid; the police fired in response. By the end of the afternoon, nearly a dozen men lay dead. The Indian government had already banned the novel.

It was different in Britain. The Conservative Thatcher and Major governments, initially forcefully but later with decreasing enthusiasm, supported Rushdie’s right to free speech, even though Rushdie had often criticised Conservative rule. In the intervening years – which Rushdie called his plague years – and after many exhausting dialogues between communities, many in Britain thought they had mastered the art of multicultural management.

The British could afford to snigger at the French for imposing laws that ban Muslim schoolgirls from wearing the veil at state-funded schools. They could say, “Never in Britain” when in Amsterdam an irate Dutch Muslim murdered Theo Van Gogh, the film-maker who liked to outrage everybody; who had most recently made a film that criticised Islamic societies for condoning violence against women.

It was supposed to be different in Britain. But for how long?

Birmingham is Britain’s second-largest city with a population of two million, and it takes pride in its multicultural mix. Its Asian community is large and is an important part of the city’s mainstream. Sikhs are fully integrated here; their men have won the right to wear their turban instead of the helmets required in various uniforms. Many Sikhs proudly recount their community’s sterling contribution to the British Army during two world wars.

As with many immigrant communities, younger Sikhs are becoming more cosmopolitan. They are not committed to the outward symbols of their faith. Many marry outside their community, many men are clean-shaven. They question their elders and their practices, and it is this troubles the more orthodox elements. The elders complain about the disintegration of the community; the younger ones feel stifled by the previous generation, most of whom are first-generation immigrants.

Behzti raises uncomfortable questions about the moral corruption within the faith. In its most controversial scene, a young Sikh woman is taken to a gurdwara (Sikh temple) where she is raped by a man who claims he had a homosexual relationship with her father. When she emerges from the experience, confused, embarrassed and angry, she is beaten by other women, including her own mother, who don’t want to believe her.

Such things, devout Sikhs insist, simply do not happen in a gurdwara.

Sewa Singh Mandha, chairman of the Council of Sikh Gurdwaras in Birmingham told BBC radio: ‘In a Sikh temple, sexual abuse does not take place, kissing and dancing don’t take place, rape doesn’t take place, homosexual activity doesn’t take place, murders do not take place.’

Concerned about accurate portrayal of their faith and at the invitation of the theatre director Sikh elders, claiming to represent Britain’s 336,000 Sikhs, had long negotiations with the theatre before the play was staged, requesting that the setting be changed from a gurdwara to a community centre. But the Rep did not budge. With hindsight, the Rep’s fateful mistake perhaps lay precisely in encouraging the impression that it would change the script, by entering into such a dialogue in the first place.

The situation turned ugly and the play closed; Bhatti’s life was threatened and she was forced into hiding. Sikh organisations, to their credit, immediately condemned the threats, but nonetheless praised the play’s closure. Welcoming the cancellation, Mohan Singh, a community leader in Birmingham, asked: ‘Will it happen again when people think peaceful protest is not going to work?’

Gurdwara means the gate to the Guru, and Sikh temples are remarkably open. As a faith that does not profess to separate its laity from the clergy, anyone familiar with the scriptures can lead prayers there, but it also means controls may be lax. Bhatti’s question is: ‘What if the men and women who manage the gurdwara are not up to the task?’

In her foreword, she says: “Clearly the fallibility of human nature means that simple Sikh principles of equality, compassion and modesty are sometimes discarded in favour of outward appearance, wealth and the quest for power. I feel that distortion in practice must be confronted and our great ideals must be restored. I believe that drama should be provocative and relevant. I wrote Behzti because I passionately oppose injustice and hypocrisy.”

But by bringing these issues into the open, Bhatti was effectively washing the community’s dirty linen in public. In the eyes of the militants, Bhatti’s play Dishonour brought dishonour on the community; shamed it in public.

Ah, that word again: shame. In his novel, Shame Rushdie writes: “Sharam, that’s the word. For which this paltry shame is a wholly inadequate translation. A short word, but one containing encyclopaedias of nuance,” which include “embarrassment, discomfiture, decency, modesty, shyness, the sense of having an ordained place in the world, and other dialects of emotion for which English has no counterparts. No matter how determinedly one flees a country, one is obliged to take along some hand-luggage … (and) what’s the opposite of shame? That’s obvious: shamelessness.”

How do you define shamelessness? Picture a metro station in Paris. A purdah-clad immigrant woman stands waiting for her train. Behind her, the advertising billboard sells toothpaste, an obligatory naked woman draped around the toothbrush.

For the devout immigrant, that billboard personifies occidental shamelessness. But her seclusion behind the veil, if against her will, is also a matter of shame; all the more so if the naked model is a second-generation immigrant herself. Such are the nuances that platitudes on multiculturalism usually fail to address.

The defiant and deviant will inevitably face the community’s shame and dishonour. When someone from a close-knit community does not respect its sense of honour that’s an act of shamelessness; and shamelessness, as one goes East, implies losing face.

As Ian Buruma shows in Wages of Guilt, which explores German and Japanese responses to World War II, German guilt resulted in a response to the Holocaust through a dramatic gesture: its Chancellor, Willy Brandt fell to his knees in December 1970 in front of the Warsaw Ghetto. It allowed Germans the ability to apologise. In contrast, Japanese Prime Ministers, concerned about face, and unable to deal with shame, continue to bow to the Yasukuni Shrine, where World War II war criminals are venerated, causing much anger in East Asian countries that suffered from Japanese occupation during the war.

The Behzti controversy goes beyond the Sikh community. It raises questions about the kind of society modern Britain wants to be. Is it to be a liberal country where free speech is honoured? Or does it want to accommodate minorities and ensure their feelings are not offended by holding its tongue?

In early January this year, evangelical Christians sent 47,000 emails to the BBC protesting its decision to broadcast the West End hit Jerry Springer: The Opera because it offends their religious beliefs. Other Christians were similarly offended when Channel Four TV promoted its Shameless Christmas Special with billboards parodying The Last Supper, in which Jesus looked merrily drunk. In December, an irate Christian toppled the waxworks models of English soccer hero David Beckham and his glamorous pop star wife Victoria Beckham at Madam Tussaud’s waxworks in London, because the couple was dressed up as Joseph and Mary in a Nativity Scene. The secular also take offence: in 2002, an angry left-leaning activist beheaded a statue of former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in London’s Guildhall.

Coexistence isn’t just about noodle shops, disco bhangra and kebab houses in Europe, but also about the co-existence of different ideas, such as those on freedom of expression. Multiculturalism is based on the premise that all faiths and customs should be tolerated and respected. But that tolerance is the product of liberal enlightenment, an outcome of centuries of churning in the West, and it is not a quality valued highly by devout believers of some of the faiths now practiced in increasingly large numbers in Europe.

Multiculturalists have wanted it both ways: they want artistic freedom, and they want to respect the feelings and sensitivities of minorities. Julian Baggini, editor of the Philosophers’ Magazine, told the Guardian of the ‘unsustainability of the liberal multiculturalist orthodoxy that maintained tolerance and respect would be enough to allow people of different beliefs to live together. Europeans had forgotten or ignored the fact that their inclusive values were not universally shared.’

At some point, the Scylla and Charybdis of outrageous statements intended to provoke and ‘right-minded’ censorship have to be confronted. Voltaire may defend the right of people he disagrees with till his death; but will those who oppose Voltaire return the favour?

Politicians prefer what Benjamin Franklin called ‘temporary safety’ to ‘essential liberty’. The Behzti controversy has coincided with discussion about a proposed new law in the UK that would make incitement to religious hatred a crime.

Artists, atheists, secularists, politicians and Christian groups have formed an unusual alliance against the bill. Rowan Atkinson, the comedian who once showed a bunch of Muslims kneeling to pray with a voice-over saying, “And the Ayatollah seems to have lost his contact lens,” has led the campaign against the bill.

The legislation is a cynical ploy to placate Britain’s Muslims, who feel estranged from the party they have traditionally backed, because of Prime Minister Tony Blair’s sustained support to the United States in the war on terror. Liberal Democrats engineered the biggest turnaround in recent British electoral history last year when in a by-election they wrested the Brent East constituency, which has a sizable minority population, from Labour’s hands.

After Birmingham, Fiona Mactaggart, a Home Office minister, spoke like a safe, cultural relativist: “When people are moved by theatre to protest … it is a great thing… that is a sign of the free speech which is so much a part of the British tradition.”

She misses the point. As Rushdie says: “It looks like we are going to have to fight and win the Enlightenment thinkers’ battle for freedom of thought all over again. One must never forget that that battle was not against the state, but the Church. (As George Santayana said over a century ago) ‘Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it’.”

Equating violent protesters with a playwright is wrong. Such pusillanimity will only embolden the intolerant, who will increasingly dictate what the rest of us should read and watch, narrowing the discourse.

That wasn’t part of any British tradition.

The Index on Censorship Book Award

In his book Soldiers of Light journalist Daniel Bergner records the experiences of a remarkable cast of characters as they look to the future of Sierra Leone and attempt to begin new lives. The book is a lively account of the moral and ethical dilemmas which the aftermath of a brutal atrocity can bring.

The Index on Censorship Film Award

Final Solution by Rakesh Sharma examines the Hindu-Muslim polarisation in Gujarat during the period February 2002 – July 2003 depicting severe human right violations that followed the burning of 58 Hindus on the Sabarmati Express. The film was banned in India.

http://www.rakeshfilm.com/finalsolution.htm

The Index on Censorship/ Hugo Young Award for Journalism

Sumi Khan is a Chittagong correspondent for the Bangladeshi magazine Weekly 2000. For her investigative articles alleging the involvement of local politicians and religious groups in attacks on members of minority communities she had received death threats, and was attacked and critically wounded in 2004.

The Index on Censorship Law Award

The New York based Center for Constitutional Rights works to uphold the rights of people with the least access to legal resources to the standards of the US Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The CCR was involved in the legal battle on Guantanamo issues.

The Index on Censorship Whistleblower Award

The sociologist and criminologist Grigoris Lazos from Greece has made the fight against human trafficking and the corruption it breeds his vocation. He is credited with almost single-handedly putting the issue of human trafficking on the government’s agenda and for mobilising civil society.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

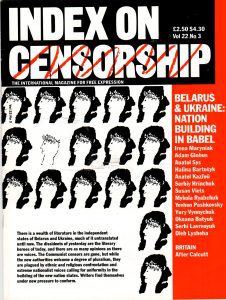

Belarus and Ukraine, the March 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_column_text]The winter 2017 Index on Censorship magazine explores 1968 – the year the world took to the streets – to discover whether our rights to protest are endangered today.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]