27 Aug 2019 | Academic Freedom, China, News, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/b21faoXVpM4″][vc_column_text]“Students in the United States must be free to express their views, without feeling pressured to censor their speech…We can and will push back hard against the Chinese government’s efforts to chill free speech on American campuses.” This is what Marie Royce, US assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs, said in her address welcoming Chinese students to American universities in July 2019.

As much a warning as a welcome, the speech illustrates the balancing act America and other western countries often perform when engaging with Chinese people and organisations on campus. The presence of the Chinese Communist Party on campuses severely limits the free expression of Chinese students, and threatens more broadly to curtail academic freedom, the right to protest, and the ability to engage with the uncomfortable truths about the Chinese government honestly.

To understand the situation, one must first understand the unique nature of the party apparatus. The CCP attempts to control not only China’s political arena but every aspect of Chinese citizens’ lives, at home and abroad, including on US campuses. Dr Teng Biao, a well-known Chinese human rights activist and lawyer, tells Index on Censorship: “It’s quite unique. The party’s goal is to maintain its rule inside China at all costs, and so it sets about making the world safe for the CCP. It is all-directional.”

That control looks very different abroad than it does at home. CCP does not control much of its foreign influence network directly. “It has different ways of implementing influence,” Teng explains. Some Chinese organisations “are directed by the Chinese government and don’t have much independence in making decisions.” However, other organisations, such as alumni networks and Chinese businesses, as well as Chinese students, have their own agency and goals, and operate largely independently.

Sources from US intelligence agencies to the New York Times have reported that the Confucius Institutes, which teach Chinese language skills to non-Chinese people, and the Chinese Students and Scholars Associations, which are student-led organisations that provide resources for Chinese students and promote Chinese culture, are directed by the CCP. The CSSA has worked closely with Beijing to promote its agenda and suppress critical speech. According to Royce, “there are credible reports of Chinese government officials pressuring Chinese students to monitor other students and report on one another” to officials, and the CSSA often facilitates this spying.

Similarly, the Confucius Institutes, have a history of stealing and censoring academic materials, have been accused of attempting to control the Chinese studies curriculum, and have been implicated in what FBI director Cristopher Wray recently described to Congress as “a thousand plus investigations all across the country” into possible CCP-directed theft of intellectual property on campuses.

Beijing’s influence is perhaps the most indirect and complex with regard to Chinese students themselves. The same day Royce made her welcome address, 300 Chinese nationalists disrupted a demonstration against China’s Hong Kong extradition bill at the University of Queensland, Australia, leading to violent clashes. On 7 August 2019 more violence between detractors of the extradition law and supporters of the CCP occurred at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, in what China’s consul general in Auckland calls a “spontaneous display of patriotism”. Earlier this year, Chinese students at MacMaster University in Canada, incensed by a lecture on the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uigher ethnic minority, allegedly filmed the event and sent the video to the Chinese consulate in Toronto, which denied involvement but praised their actions as patriotic. [/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/kW3c211dy8g”][vc_column_text]Speaking to Index about the Queensland protest, Dr Jonathan Sullivan, director of China Programs at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute, said “Many Chinese students have passionately held views and they sometimes mobilise to voice them. I don’t think it’s helpful to see such mobilisations as being the work of the party, although there is also evidence that party/state organisations sometimes provide help.” Sullivan notes, however, that their passion and convictions “are themselves a product of the authoritarian information order created by the party-state” and that “there is among Chinese students potential to react in an organised way.”

Isaac Stone Fish, a prominent journalist and a senior fellow at the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations in New York City told Index “[The party is] very effective generally at keeping students in an ideological framework,” convincing them, for instance, that “the communist party and China are the same” and thus motivating them to protect the party. However,he agrees that students’ convictions belong to them. “It’s ok for Chinese students to feel that Beijing’s policies are correct,” he says. Problems only arise when they try to control the conversation.

As the extent of the CCP’s influence is gradually revealed to the public, there have been fears that governments will retaliate indiscriminately and restrict visas for all Chinese students abroad, or withhold them specifically from members of the CSSA. Tensions over immigration, especially in the US, mean such a reaction is possible, but as Sullivan says: “We should keep in mind that most Chinese students care about their degree and getting on in life, and we all must resist any temptation to homogenise — let alone demonise — them.” Stone Fish concurs. “There is…a danger of a racially-tinged backlash against Chinese people, which would be an ethical and strategic mistake.”

Sullivan is concerned that many universities treat Chinese students like an easy source of income instead of treating them as students with unique and pressing needs. They have that in common with the party itself. One of the biggest dangers in dealing with the CCP, explains Stone Fish, is “its willingness to use Chinese students as bargaining chips” directing them to some universities and way from others to encourage political conformity. Western institutions are vulnerable to such a tactic, Teng claims, because they “care about money more than universal values,” and “They don’t profoundly realise” that the CCP “has become an urgent threat.”

So far, the western response to the issue has been inconsistent and uncertain. “I think universities need to develop a much clearer understanding of the issues,” Sullivan says. “These can be complex and university administrators are not generally China specialists who are able to identify the nuances, which makes policy and provision inadequate and potentially unbalanced.” Going forward, Stone Fish asserts, we should be “Educating college administrators about how the party works,” and “having universities work together.” Cooperation is essential, because “Beijing prefers to negotiate one-on-one,” but as a bloc, Universities have leverage of their own.

Demand for western education in China is strong and continues to grow, especially among the Chinese elite and middle class. However, universities can only use that demand to resist pressure from the CCP if they coordinate their response. Stone Fish concludes, “I think the greatest danger is giving in to Beijing’s demands not to have certain speakers, or allow the party to prevent certain voices from being heard.” [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1566913121795-e09fc4f8-7d31-10″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Aug 2019 | About Index

Summer is here! As Index gets its tent ready for another festival this weekend, I wanted to share some highlights from the past few months and give you a sneak peek of what we have in store for the autumn.

Above right, Jemima Foxtrot performs at Latitude Festival.

This Friday, we’ll be gathering festival goers around the campfire for a series ofuncensored folk tales at the Cambridge Folk Festival, where we are this year’s talks partner. Cambridge comes hot on the heels of our story-telling sessions at Latitude where writers including Scarlett Curtis, Max Porter and Jemima Foxtrot entertained crowds with wild stories.

Speech of a different kind was in focus at a talk earlier in July when UN rapporteur David Kaye discussed the thorny question of who polices speech online. Our magazine launch and summer party at the Goethe Institut, with German crime writer Regula Venske, was also a chance to reflect on the ways censorship creeps up to become authoritarianism.

Other events included two special talks in London and at the Hay Festival to mark the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square killings. Speakers included authors Xinran and Karoline Kan, journalist Tania Branigan and academic Jeff Wasserstrom.

China will be in focus again in October when we have an exclusive screening of the film China’s Artful Dissident, which features the work of leading political dissident cartoonist Badiucao. Badiucao, who revealed his identity earlier this year after years of anonymity and who is flying from Australia to attend, will be in conversation with cartoonist Martin Rowson after the film. This is an invitation only event. Please email [email protected] if you would like to attend.

At the end of September, Index celebrates the freedom to read. Watch out for Banned Books Week events at the British Library and Foyles bookshop as well as at independent bookshops and libraries around the UK where midnight openings will celebrate the launch of Margaret Atwood’s new book ‘The Testaments’.

Press freedom in focus

In advocacy, we were delighted at news that the investigation into Northern Irish reporters Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey was dropped in May. Index – alongside colleagues English PEN – intervened in the judicial review of their case and we are grateful for the support of Phoenix Law in Belfast and Doughty Street Chambers in London. Birney and McCaffrey had their homes and office raided last year following their documentary investigating police collusion in the murders of six men.

From left: Freedom of Expression Awards Journalism Fellows Zaina Erhaim (2016), Zaheena Rasheed (2017) and Wendy Funes (2018) in the Index booth at the Defend Media Freedom conference in July.

Media freedom is the focus of a major campaign spearheaded by the UK and Canada this year. I spoke on the issue at the UK’s launch of its annual human rights report and Index played an active role in a global conference hosted in London in July to launch the campaign. We were excited to see so many Index fellows there, including journalism fellows Zaina Erhaim, Zaheena Rasheed and Mimi Mefo, who all spoke on panels at the event, as well as Wendy Funes, NetBlocks and CRNI. We’ve also published reports looking at the wave of physical threats that journalists are facing in Russia, Turkey and Ukraine — drawn from our latest media monitoring project.

Current arts fellow Zehra Dogan had an exhibition at the Tate in May and was also one ofthe designers of flags developed to mark the 70th anniversary of the UN declaration on human rights.

Also in arts, Index continued to raise questions about the UK’s policing of drill music and spoke at the launch of a new single by two artists who are subject to controversial new orders that are forcing musicians to censor their work.

Knowledge sharing

Our expertise is in high demand. In May, Index launched a new advisory service for arts organisations facing censorship, offering consultancy services, workshops and training. We also continue to provide expertise through the media, and have featured widely in international and national press and broadcast. Head of advocacy Joy Hyvarinen has been active in raising Index’s concerns about the UK’s strategy for online safety. We also gave evidence to Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights about harassment ofMPs – on and offline.

We are recruiting for two new roles over the summer. The Head of Communications & Media and Senior Partnerships Manager positions are currently being advertised and we look forward to welcoming new additions to the Index family who will help us spread the free speech message even further.

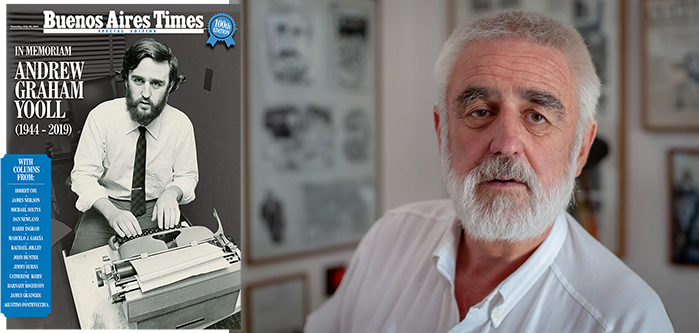

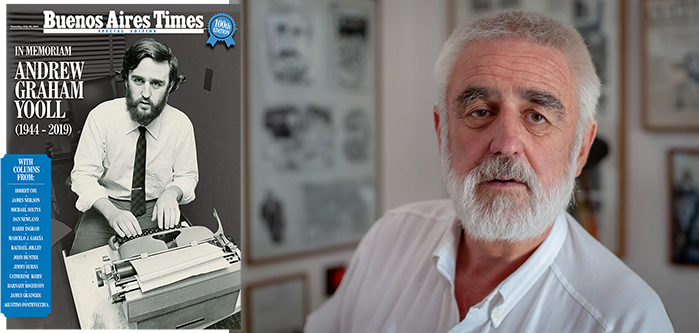

Andrew Graham-Yooll

Finally, we were sorry last month to learn of the death of a great Index friend and freespeech champion – former editor of Index magazine, Andrew Graham-Yooll, who was a leading figure in the reporting of Argentina’s repressive regime in the 1970s and 1980s. Andrew’s family have kindly asked that people give to Index in Andrew’s memory. If you would like to do this, please visit the justgiving page.

As another former Index colleague, Matthew d’Ancona, wrote in a recent article, the right to free speech is needed not by the few but by everyone – and we are grateful to have had known individuals like Andrew who help us maintain that fight.

18 Jun 2019 | Events, News, Saudi Arabia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107402″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]On 17 June 2012, blogger Raif Badawi was arrested in Saudi Arabia for “criticising Islam through electronic means” and for apostasy (the abandonment of Islam by a Muslim). He was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison and 600 lashes, which was later extended to 10 years and 1,000 lashes. Seven years later, his imprisonment continues to spark outrage around the world.

“I think it’s important to show to the Saudi Arabian government that we’re still highlighting these cases even though it’s been seven years since Raif’s imprisonment,” Perla Hinojosa, fellowships and advocacy officer at Index on Censorship said at the vigil held for Badawi outside the Saudi embassy on Monday 17 June.

Badawi started one of the only fora on which Saudi Arabians could communicate freely, especially about issues related to secularism, atheism and liberalism. Though he never formally denounced the Saudi government, his website, Saudi Liberal Network, eventually caught the government’s attention for his posts questioning the country’s adoption of Sharia Law and theocracy. After his arrest, the website was shuttered by the Saudi government. On 30 July 2013, Badawi was convicted, and one and a half years later, on 9 January 2015, he received the first 50 of his lashes.

“In particular it was the lashes that drew widespread international condemnation to what has happened….it does take something particularly horrific to mobilise that kind of action,” said Rebecca Vincent, UK bureau director for Reporters Without Borders. Badawi’s case highlights the Saudi government’s media suppression and harsh corporal punishment.

Badawi’s health declined after his first 50 lashes. The remaining 950 were indefinitely postponed and remains incarcerated. His wife, Ensaf Haidar, and their three children escaped to Canada shortly before his arrest, where they advocate for his release and have legal status as refugees. Badawi faces a 10-year travel ban after his release from prison, though he hopes to one day rejoin his family.

Though Badawi is the face of the struggle for free press in Saudi Arabia, he is far from the only one to be targeted. His website lists four others who have been targeted by the governments of Saudi Arabia or Bahrain for speaking out against government abuses, and there are reports of countless others who have received violent or even capital sentences for offenses as benign as tweeting about atheism. Cat Lucas, programme director of the Writers at Risk Programme at English PEN, explained that “being able to use him to highlight other cases is very helpful.”

Though drawing attention to the issues through personal stories like Badawi’s is important, there has been minimal progress in securing his release. “Even though it was initially condemned internationally we’ve not really seen anything happen as a consequence,” says Vincent. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia has made changes in certain areas, like granting women the right to drive, however the small improvements have not extended to media freedom, Lucas noted. Vincent said that though the Crown Prince’s policies may have initially inspired hope in many Saudis, “when you look at… [policies like] the right of women to drive, many of the activists who campaigned for that are behind bars themselves.”

Lucas said that though–after seven years of protesting for Badawi’s release–the fight for media freedom in Saudi Arabia might seem like an uphill battle, it is important not to lose hope. “It’s the role of organisations like English PEN and Index on Censorship to keep up the pressure on governments including our own, even when it’s many years after the initial arrest or detention of one of our colleagues around the world,” she said.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1560855350907-6af08b0a-d8a9-4″][/vc_column][/vc_row]