6 May 2025 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, News, Volume 54.01 Spring 2025

This article first appeared in Volume 54, Issue 1 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled The forgotten patients: Lost voices in the global healthcare system, published on 11 April 2025. Read more about the issue here.

In August 2022, one of the largest surveillance scandals in modern Greek history came to light. Often referred to as the Greek Watergate, it revealed that officials within the government and the National Intelligence Service (EYP), including associates of prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, had been involved in deploying Predator – a spyware tool developed by former Israeli military personnel.

Intellexa, the founding company, had sold multiple licences to the EYP and, according to reports from The Guardian, Reuters and elsewhere, the EYP had subsequently sent messages intended to infect mobile phones and enable electronic surveillance of certain individuals.

Hundreds were targeted, including political opponents of the ruling New Democracy party, journalists, and even government ministers. Among those targeted, the most prominent politician identified was Nikos Androulakis, leader of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and leader of the opposition.

The Greek government continues to deny ever having purchased or used Predator spyware. On 5 August 2022, during a live television address, Mitsotakis responded to revelations of wiretapping. His inability to provide credible explanations for how the EYP obtained the spyware, combined with his denial of any knowledge of the scandal, heightened suspicions among politicians and journalists. Notably, he had restructured the EYP on the first day of his premiership in 2019, placing it directly under the control of the prime minister’s office. Consequently, many questioned how he could have been unaware of such activities.

Nearly three years have passed since the scandal emerged, yet most questions remain unanswered. The prosecutor investigating the case closed the probe last July and refused to further grill individuals linked to the deployment of Predator.

The government allegedly interfered with aspects of the inquiry – including the deliberations of certain committees – and hindered the work of oversight bodies such as the communication security regulator, reported Politico.

Meanwhile, courts have declined to prioritise journalistic and investigative efforts that continue to uncover evidence related to the wiretapping activities.

Unsurprisingly, the government’s actions extended beyond covert surveillance. Many people allegedly investigated for their involvement – including Mitsotakis’s nephew Grigoris Dimitriadis, the former secretary-general in the prime minister’s office – fought back by aggressively pursuing lawsuits against journalists and media outlets investigating the scandal, including Efimerida ton Syntakton and Reporters United.

These weren’t just ordinary lawsuits but strategic lawsuits against public participation (Slapps) – deliberately-initiated legal actions aimed at intimidating and silencing critics.

The party filing a Slapp – in this case Dimitriadis – typically does not intend to win the case. The objective is to overwhelm the defendant with legal expenses, fear and exhaustion, ultimately compelling them to cease their reporting or opposition.

Nevertheless, while investigating how the surveillance activities were carried out, Greek journalists managed to uncover something far more significant than they had anticipated – a system that undermines the democratic standards typically upheld by EU member states.

In this regard, Mitsotakis closely resembles Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, who has systematically controlled media organisations by placing them under direct supervision, suppressing criticism and dissent.

Since 2019, corruption has flourished under Mitsotakis’s administration and the government appears to have engaged in favouritism and a deliberate dismantling of fundamental human rights – undermining the very foundations of democracy in Greece.

He also allocated funding to the press – both during the Covid-19 pandemic and amid the Ukraine-Russia conflict – in ways that were widely condemned as attempts to financially control specific media outlets.

The funding excluded certain newspapers that were critical of the government, raising concerns about selective support for government-friendly sources, but did include far-right publications affiliated with Kyriakos Velopoulos (an MP known for spreading disinformation) and even non-existent news outlets.

The government has been accused of deploying an extensive network of online trolls on X and TikTok for damage control, including a dedicated war room called Omada Alithias which serves as its mouthpiece. These operations systematically target and suppress dissenting voices, critical media outlets and investigative journalists – particularly those who have exposed the wiretapping scandal – through co-ordinated attacks and gaslighting tactics. These have included downplaying the scandal and dismissing investigative work as fake news.

The impact on press freedom has been dire, with Reporters Without Borders (RSF) confirming some of the worst fears expressed by journalists. In the RSF index, Greece plummeted to 107th position in 2023 before improving somewhat in 2024, rising to 88th. Despite RSF’s concerns, Mitsotakis has dismissed the organisation’s findings and labelled any criticism of Greece’s press freedom as “crap”.

Research demonstrates that democratic backsliding invariably begins with media manipulation and the imposition of excessive control – tactics that Mitsotakis has prioritised since the start of his tenure.

The situation in Greece reveals a complex phenomenon, described by Dutch political scientist Matthijs Rooduijn as a “snowball effect”. Centrist parties previously perceived as moderate, such as New Democracy, are increasingly cloaking themselves under a liberal façade with the explicit intent of undermining democratic norms.

Instances such as those seen in Greece illustrate that Europe is confronted not only with an existential threat to its democratic institutions but also with the danger of normalising illiberal policies. This troubling trend is underscored by the EU’s increasingly permissive approach to surveillance, where the potential consequences are acknowledged yet policy measures remain inadequately implemented.

Additionally, the sustained erosion of press freedoms further exacerbates the vulnerability of democracy. These developments indicate a systemic weakening of safeguards, and the issue is further illustrated by the close and often opaque connections among elected officials which undermine transparency. Without decisive and comprehensive interventions, Europe risks undermining the very foundations that ensure its democratic resilience and integrity.

Greece serves as a prime case study of this troubling trajectory. The country endured a military dictatorship from 1967 to 1974, before democracy was re-established. It has also experienced a serious socio-economic crisis from 2010 to 2019, the subsequent neoliberal restructuring of its economy and a recent resurgence of neo-Nazism. Some of these phases of extreme instability are common in post-authoritarian countries that struggle to uphold the rule of law and democratic principles.

The legacy of the wiretapping scandal cannot be underestimated or overlooked. New Democracy and its successors may attempt to preserve these tools of suppression, potentially leading to further democratic backsliding. Without determined efforts to eliminate such practices, freedom of the press will continue to deteriorate, lacking the legal safeguards needed to prevent unconstitutional measures that can cause long-term damage.

2 May 2025 | Africa, Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Hong Kong, Israel, Kenya, Middle East and North Africa, News, Palestine, Uganda, United Kingdom

In the age of online information, it can feel harder than ever to stay informed. As we get bombarded with news from all angles, important stories can easily pass us by. To help you cut through the noise, every Friday Index will publish a weekly news roundup of some of the key stories covering censorship and free expression from the past seven days. This week, we cover the arrest of a prominent Palestinian journalist, and how the Court of Appeal struck down anti-protest legislation in the UK.

Press freedom infringed: Prominent Palestinian journalist detained by Israeli forces in West Bank

On Tuesday morning, Palestinian journalist Ali Al-Samoudi was arrested by Israeli forces in the city of Jenin in the northern West Bank during a raid on his son’s home. Israeli officials stated that he was suspected of the “transfer of funds” to a terrorist organisation – a claim made with no evidence, and that Al-Samoudi’s family strongly denies. The arrest has also been condemned by the Palestinian Journalists’ Syndicate.

Arbitrary punishment for Palestinian journalists has become a recurring theme; Reporters Without Borders has named Palestine as “the world’s most dangerous state for journalists”. Nearly 200 Palestinian journalists have been killed in Gaza since the 7 October 2023 Hamas attacks and ensuing Israel-Hamas war, and the Committee to Protect Journalists reports that at least 85 journalists have been arrested in Gaza and the West Bank.

Al-Samoudi has been targeted before; in May 2022, he was working near the Jenin refugee camp when Israeli forces shot and injured him, killing his colleague Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu-Akleh in the same attack. Over his career, Al-Samoudi has never faced accusations of terrorist affiliation, according to his family. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has reportedly said that he has now been transferred to Israeli security forces “for further treatment”.

The right to protest: UK anti-protest law defeated in the Court of Appeal

Protest rights have been under attack across the globe in recent years, and some of the most notable anti-protest legislation (the Public Order Act 2023) has been passed in the UK. This has drawn condemnation from human rights groups as they have made it more difficult to demonstrate within the bounds of the law, and have given the police more power to disrupt peaceful protest.

But on Friday 2 May, the London Court of Appeal dealt a blow to the ambitions of the UK Government to crack down on protests by agreeing with last year’s High Court ruling that anti-protest regulation was made unlawfully under the former Conservative government. The government appealed against this, but the Court of Appeal has now dismissed that appeal.

Human rights group Liberty, which initially challenged the anti-protest regulation, has described the decision as “a huge victory for democracy”.

Former Home Secretary Suella Braverman had tabled amendments to the Public Order Act 2023 using so-called Henry VIII powers to lower the threshold at which police could restrict protests to “more than minor” levels of disruption – a move which the High Court ruled as unlawful in May 2024.

Akiko Hart, director of Liberty, has stated that this ruling should serve as a “wake-up call” for Labour, who so far in its tenure in government have backed many of the same anti-protest laws as the Conservatives.

Attackers exposed: Kenyan government under fire after documentary investigates killing of protesters

On Monday, BBC Africa Eye released a documentary exposé that detailed how in June 2024 Kenyan security forces shot and killed three unarmed anti-tax protesters who were demonstrating against the Kenyan Government’s controversial finance bill.

According to the exposé, the protesters were posing no threat to the police officers at the time of the incident, and the BBC’s investigators claim they have identified the individuals who fired shots into the crowd.

The exposé has renewed calls for justice to be served to those officers who carried out the killings, with human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and the Kenya Human Rights Commission putting pressure on the Kenyan government to follow up on the BBC’s findings and ensure the identified officers “face the law”.

Government officials have been split on the documentary; a spokesperson called the documentary “one-sided”, and one legislator even called for the BBC to be banned in Kenya – while opposition politicians have largely been supportive of the exposé’s findings, with the main opposition coalition stating that the “execution of peaceful protesters was premeditated and sanctioned at the highest levels”.

Four years on: Pro-democracy lawmakers released from prison in Hong Kong

In 2021, the Hong Kong 47 were charged under a national security law imposed by the Chinese government. The 47 were made up of prominent pro-democracy campaigners, councillors and legislators in the city, accused of attempting to overthrow the government by holding an unofficial “primary” to pick opposition candidates in local elections.

The national security law was brought into effect in response to the wave of pro-democracy protests that swept across Hong Kong in 2019. Up to two million people took to the streets to protest peacefully; this was met with batons, tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and water cannons by the Hong Kong police.

It wasn’t until November 2024 that the campaigners were sentenced and jailed; sentences ranged between four and 10 years, with many of the Hong Kong 47 having been imprisoned since their initial arrest in 2021. The jail sentences have been widely condemned by democratic nations.

But this week, on Tuesday 29 April 2025, the first wave of activists were released from prison. Four individuals, including prominent opposition politician Claudia Mo, were among those imprisoned since 2021, and this was taken into consideration for their sentence – after more than four years behind bars, they have been set free.

Military-level punishment: Ugandan president accused of sending dissenters to military court

Opposition leaders in Uganda have accused Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni of silencing political dissenters and opposition by trying them before military courts rather than civilian courts.

This practice was attempted against opposition politician Kizza Besigye last year – he was abducted in Kenya in November and tried before a military tribunal for treason. Besigye, 68, underwent a 10-day hunger strike in protest at his detention, before a ruling by the Supreme Court demanded that his trial be moved to a civilian court. The landmark ruling found that trying civilians in military courts was unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court ordered all such cases to be transferred. If Besigye, 68, is found guilty of treason, he could be sentenced to death.

While Besigye’s case was eventually moved to a civilian court, Museveni has not been deterred. The government is attempting to push through a law allowing civilians to be tried in military courts. Despite its current illegality, the government has continually weaponised these courts to abuse political opponents, such as supporters of the National Unity Platform (NUP), led by popular opposition politician Bobi Wine (Robert Kyagulanyi). According to Amnesty international, more than 1,000 civilians have been unlawfully convicted in military courts in Uganda since 2002.

29 Apr 2025 | Middle East and North Africa, News, Palestine, Volume 54.01 Spring 2025

This article first appeared in Volume 54, Issue 1 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled The forgotten patients: Lost voices in the global healthcare system, published on 11 April 2025. Read more about the issue here.

Most children say their first word between the ages of 12 and 18 months. But Fatehy, a Palestinian boy living in Jabalia City in Gaza, is four years old and is still barely talking.

When he does speak, he says the same words over and over again – “scared”, “bomb” and “fighters”. While he used to say words such as “mumma” and “bubba”, his language progression has reversed, and now he is mostly silent.

He has been displaced roughly 15 times and experienced several close family deaths, including those of his mother and sister. At one point, he was discovered on a pile of bodies and was presumed dead. He was rescued purely by luck when a family member saw that he was still gently breathing.

His cousin, Nejam, is three years old. His speech is also very limited, and is mostly reserved for the names of tanks, drones and rockets. He has been pulled from rubble several times.

Neither child has access to school, nursery or social activities with friends. Medical treatment is severely limited, and they have been unable to access any of the few speech therapists available. Food scarcity also means they have been unable to learn basic vocabulary about ingredients or meals.

Dalloul Neder, a 33-year-old Palestinian man living in the UK since 2017, is their uncle.

“The only thing they’ve been listening to is the bombing,” he told Index. “That’s why they are traumatised.

“They miss their families, grandparents, mums and family gatherings around the table. They realise something is not right but they can’t express their pain.”

Psychological trauma is extremely common for children living in warzones. This can cause mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and panic attacks, but also communication problems, such as losing the ability to speak partially or fully, or developing a stammer. For younger children such as Fatehy and Nejam, war trauma can impact cognitive development, causing language delays and making it hard to learn to speak in the first place.

In December, the Gaza-based psychosocial support organisation Community Training Centre for Crisis Management published a report based on interviews it had conducted with more than 500 children, parents and caregivers. Nearly all the children interviewed (96%) said they felt that death was “imminent” and 77% of them avoided talking about traumatic events. Many showed signs of withdrawal and severe anxiety. Roughly half the caregivers said children exhibited signs of introversion, with some reporting that they spent a lot of time alone and did not like to interact with others.

Katrin Glatz Brubakk is a child psychotherapist who has just returned to Norway from Gaza, where she was working as a mental health activities manager with Médecins Sans Frontières in Nasser Hospital, Khan Younis. Her team offers mental health support to adults and children, but mainly to children dealing with burns and orthopaedic injuries, mostly from bomb attacks.

She told Index that children tended to present with “acute trauma responses”, while the long-term impacts on their psychological wellbeing were yet to be seen.

In her work, she typically sees two types of responses – either restlessness and being hard to calm down, or becoming uncommunicative and withdrawn. She believes the latter is significantly harder to spot and therefore under-reported.

“We have to take into account that it’s easier to detect the acting-out kids, and it’s easier to overlook the withdrawn kids or just think they’re a bit shy or quiet,” she said.

She commonly saw children experiencing extreme panic attacks due to flashbacks, where any small thing – such as a door closing or their parent leaving a room – could trigger them. She noted they would often let out “intense screams”.

But some children have become so withdrawn they do not scream or cry at all. Some have even fallen into “resignation syndrome”, a reduced state of consciousness where they can stop walking, talking and eating entirely.

Brubakk recalled one “extreme case” of a five-year-old boy who was the victim of a bomb attack and witnessed his father die. He fell completely silent and did not want to see anybody, and also hardly ate.

“When children experience severe or multiple trauma, it’s as if the body goes into an overload state,” she said. “In order to protect themselves from more negative experiences and stress, they totally withdraw from the world.”

Living in a warzone can also mean that children’s “neural development totally stops”, she said, as they lose the opportunity to play, learn new skills, learn language and understand social rules. “The body and mind use all their energy to protect the child from more harm,” she said. “That doesn’t affect the child only there and then, it will have long-term consequences.”

This is made worse by a lack of “societal structures”, such as schools. “[These offer a] social arena, where they can feel success – there’s no normality, there’s no predictability.”

Therapy can be used to encourage children to speak again, particularly with creative methods such as play and drawing therapy. Brubakk explained how through “playful activities” and “small steps”, her team were able to encourage children to communicate.

Recently, she managed this through the creation of a makeshift dolls house. A young girl had been burnt in a bomb attack. Her two brothers had been killed and her two sisters injured, with one of them in a critical state. It was uncertain whether her sister would survive.

The girl wasn’t able to speak about her experiences until Brubakk helped her create a dolls house using an old box, some colouring pens and tape, plus two small dolls the girl had kept from her home. She named the dolls after herself and her sister, and was able to start expressing her grief and fears, as well as her hopes for the future.

“So through a very different type of communication, she was able to express how worried she was about her sister, but also process some of the experiences she had,” said Brubakk.

A report published by the non-profit Gaza Community Mental Health Programme (GCMHP) includes success stories of children who have benefited from creative communication. Alaa, a 12-year-old boy who sustained facial injuries after a bombardment and then later experienced forced evacuation by Israeli forces from Al-Shifa hospital, developed recurring nightmares, verbal violence, memory loss and an aversion to talking about his injuries. A treatment plan of drawing therapy and written narrations of the events helped him to become more sociable, and now he visits other injured children to share his story with them and listen to theirs.

Sarah, meanwhile, is a 13-year-old girl who developed post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic mutism after having an operation on her leg following a shell attack. She didn’t speak for three months and would use only signals or write on pieces of paper. The GCMHP worked with her on a gradual psychotherapy plan, including drawing and play therapy. After three weeks, she started saying a few words, and she was eventually able to start discussing her trauma with therapists.

Trauma-related speech issues are complex problems that can be diagnosed as both mental health issues and communication disorders, so they often benefit from intervention from both psychotherapists and speech and language therapists.

Alongside developing speech issues due to war, living in a warzone can worsen speech problems in children with pre-existing conditions. For example, those with developmental disabilities such as autism may already have selective mutism (talking only in certain settings or circumstances), and this can become more pronounced.

Then there is behaviour that can become “entrenched” due to their environments, Ryann Sowden told Index. Sowden is a UK-based health researcher and speech and language therapist who has previously worked with bilingual children, including refugees who developed selective mutism in warzones.

“Sometimes, [in warzones,] it’s not always safe to talk,” she said. “One family I worked with had to be quiet to keep safe. So, I can imagine things like that become more entrenched, as it’s a way of coping with seeing some really horrific things.”

She described a “two-pronged” effect, with war trauma causing or exacerbating speech issues, and a lack of healthcare services meaning that early intervention for those with existing communication disorders or very young children can’t happen.

There is an understandable need to focus on survival rather than rehabilitation in warzones, she said, and a lot of allied health professionals, such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists and psychotherapists, are diverted to emergency services.

This was echoed by Julie Marshall, emerita professor of communication disability at Manchester Metropolitan University and formerly a speech and language therapist working with refugees in Rwanda. Her academic research has noted a lack of speech and language therapists in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) in general.

“In many LMICs, communication professionals are rare, resulting in reliance on community members or a community-based rehabilitation workforce underprepared to work with people with communication disorders,” she wrote in a co-authored paper in British Medical Journal Global Health.

For children who already have speech or language difficulties, losing family members who are attuned to their other methods of communication, such as gestures or pointing, can make the issue worse.

“If you are non-verbal, you may well have a family member who understands an awful lot of what we would call ‘non-intentional communication’,” said Marshall. “If you lose the person who knows you and reads you really well, that’s huge.”

In warzones, Marshall and Sowden both believe that speech and language therapy is more likely to be incorporated alongside medical disciplines dealing with physical injury, such as head or neck trauma or dysphagia (an inability to swallow correctly). This belief was mirrored by the work of Brubakk, whose mental health team at Nasser Hospital worked mostly with patients who had been seen in the burns and orthopaedics departments.

One of the most valuable things that can be done is to train communities in simple ways to help children who may be living with a speech or language difficulty, Marshall believes, shifting away from treating a single individual to trying to change the general environment.

“There are lots of attitudes around communication disabilities that could be changed,” she said. For example, it is often misjudged that children with muteness may not want to talk, and they are subsequently ignored rather than patiently and gently interacted with.

Despite a lack of healthcare provision, there are some professionals on the ground in Gaza. In 2024, the UN interviewed Amina al-Dahdouh, a speech and language therapist working in a tent west of Al-Zawaida. She said that for every 10 children she saw, six suffered from speech problems such as stammering. In a video report, al-Dahdouh held a mirror up to children’s faces as she tried to teach them basic Arabic vocabulary and show them how to formulate the sounds in their mouths.

But the destruction of medical facilities such as hospitals and a lack of equipment have made it difficult for professionals to do their jobs. Mohammed el-Hayek is a 36-year-old Palestinian speech and language therapist based in Gaza City who previously worked with Syrian child refugees in Turkey.

“Currently, there are no clinics or centres to treat children, and there are many cases that I cannot treat because of the war, destruction and lack of necessary tools – the most important of which is soundproof rooms,” he told Index. “Before the war, I used to treat children in their homes.”

Soundproof rooms can be used by speech and language therapists to create more private, quiet and controlled spaces that reduce distracting external noises including triggering sounds such as gunfire or bombs.

The most common issue he has encountered is stammering, which he says becomes harder to tackle the longer it is left untreated.

“Children are never supported in terms of speech and language,” he added. “[It is] considered ‘not essential’ but it is the most important thing so that the child can communicate with all their family and friends and not cause [them] psychological problems.”

For many of these children, the road to recovery will be long. Mona el-Farra, a doctor and director of Gaza projects for the Middle East Children’s Alliance, told Index that the “accumulation of trauma” caused by multiple bombardments meant that even those receiving psychological support were offered little respite to heal.

One glimmer of hope is that cultural barriers around trauma appear to be lifting, which has encouraged people to stop self-censoring around their own mental health.

“There is no stigma now [around mental health],” said el-Farra. “The culture used to be like this, but not anymore. You can see that 99% of the population has been subjected to trauma. [People] have started to express themselves and not deny it.”

At the time of publishing, the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas had broken down and bombardment had restarted. When a permanent ceasefire is finally established and healthcare provision in Gaza can be rebuilt, there will need to be a concerted effort to support children with their psychological and social rehabilitation as well as their physical health. Hopefully then they can start to come to terms with their experiences and tell their stories – otherwise, they could be lost forever.

23 Apr 2025 | Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News, Palestine

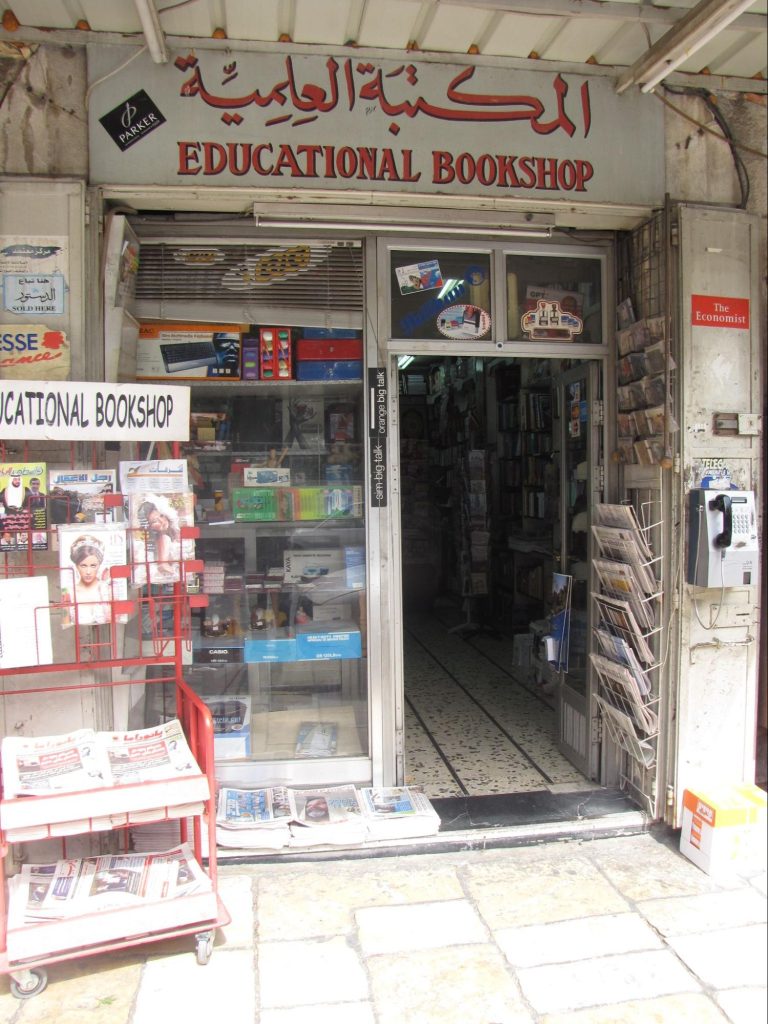

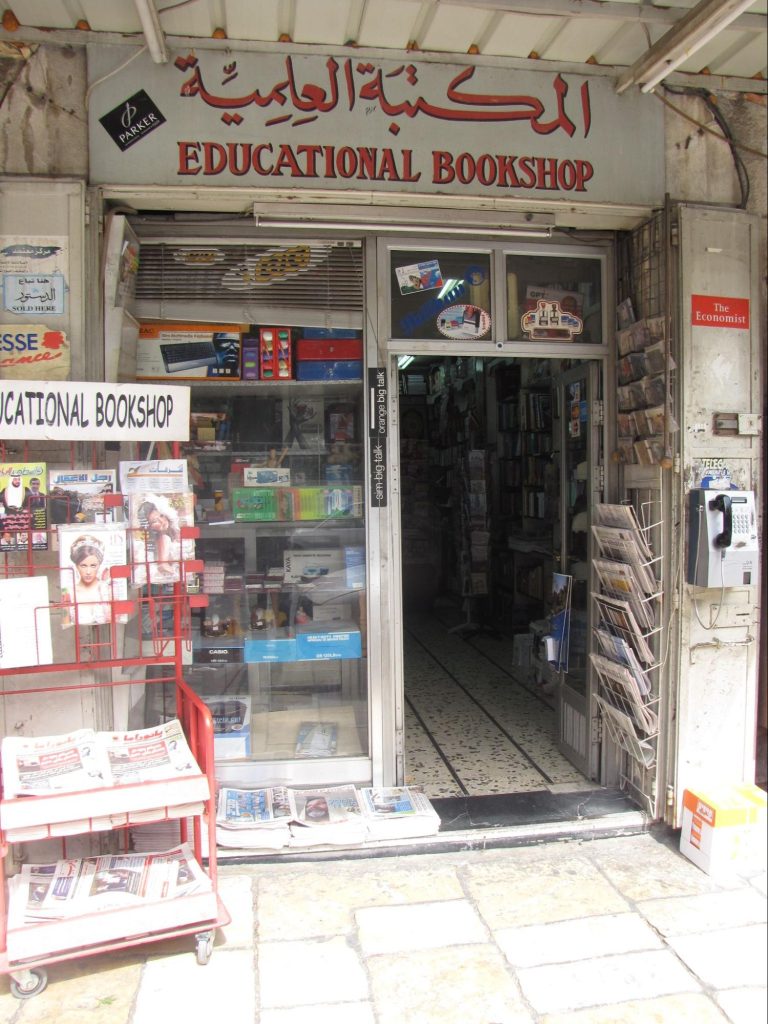

For more than 40 years, the Palestinian-run Educational Bookshop in occupied East Jerusalem has provided both locals and tourists with access to a wealth of books, magazines and cultural events, establishing itself as a cultural hub within the historic city. Now, its very existence is under threat.

On 9 February 2025, undercover Israeli police stormed the bookshop and its Arabic-language counterpart next door.

“It was a Sunday afternoon. I was having a good time with my daughter who’s 10 years old,” Mahmoud Muna, co-owner of the bookshop, told Index on Censorship.

The officers started pulling books from the shelves and examining the covers.

“Any cover that had a flag, map, words, keywords like ‘Palestine’, ‘Nakba’ or ‘Gaza’ was deemed suspicious,” said Mahmoud. “Then they Google translate[d] the cover or the blurb or the back page, and they start[ed] creating two piles on the floor, one for the books that they didn’t want to take and another pile for the books that they wanted to take. [This was] completely irrespective of the books and what they mean to us.”

The police put around 300 confiscated books into bin bags, then took Muna and his nephew Ahmad Muna into custody on charges that their books were causing “public disorder”.

“They took us to the police station where we were detained the first night and then taken to court the second night… we were released after 48 hours, myself and my nephew, who was manning the Arabic branch. [We were put] on bail: five days’ house arrest and 20 days away from the bookshop.”

Most of the confiscated books were returned. On 11 March 2025, the police raided the bookshop again, taking 50 books and arresting Mahmoud’s 61-year-old brother and co-owner, Imad Muna. Imad was released a few hours later. The police confiscated books by Banksy, Ilan Pappé and Noam Chomsky, among others.

“They came again and they replayed the whole scenario again. It was just that we were a bit more ready legally. It happened during the morning hours and it was my brother who was in the shop. So we were able to act very quickly and [he was released] before the night,” Mahmoud said.

The Educational Bookshop was founded in 1984 by Mahmoud’s father, Ahmad Muna, a Jerusalem-born teacher. The bookshop has remained a family business ever since.

“For 40 years, we’ve been in operation, trying to serve our community, trying to contribute to social, political, cultural change in a city that is torn between political upheavals. And we believe that books and conversation around books can be an important carrier, if you like, for the conversation. It can open up a space for conversation,” Mahmoud said.

Photo by Mahmoud Muna

These raids are not isolated incidents; they form part of a wider campaign by the Israeli government to crack down on free expression, which has been intensified by the emergence of the far-right within Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government and worsened still by Hamas’s incursion on 7 October 2023 and the war in Gaza that has followed.

Recently, authorities have also begun censoring Israeli films critical of the government, as well as events and festivals that discuss Gaza, Palestinians or the 1948 Nakba. The government has started using a revived British Mandate-era law from 1917, which allows the Culture and Sport Ministry to review films before they are screened.

“I think the political climate has really changed. Maybe the war is part of that, but it is not the reason. There is a policy of oppression towards cultural institutions. If you look at theatre, music schools, youth clubs, women’s associations for the last five, six, seven years even before the war, they have been suffering,” Mahmoud said.

Mahmoud says that he and his family have no intention of giving into the authorities’ intimidation tactics.

“We are determined, we’re not gonna give up. It makes me angry, but it also makes me believe even stronger in the power of books and words and literature. And it also opens my eyes even further to the importance of our work in our society.”

Above all, he calls on the international community to speak out against the erosion of democratic values unfolding in Israel and Palestine today.

“If we really believe in what we say, and we really want progressive liberal societies and freedom of expression in Turkey or China or Russia, then we also need to demand them in places like Jerusalem as well.”