20 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia

On 6 November 2010, prominent Russian journalist Oleg Kashin was badly beaten with a steel pipe on his doorstep and nearly killed. He suffered a broken skull and injuries to his legs and hands — including broken fingers and one amputated digit. He was hospitalised in a coma and spent months recovering. Dmitry Medvedev, who was then President of Russia, visited him promising that the case would be solved and the attackers would be punished.

At the time, Kashin’s editor told the BBC that the attack was retribution for articles he had written and that he had recently reported on anti-Kremlin protests and extremist rallies.

Two months prior to the assault, Kashin had had an online quarrel with Andrey Turchak, the powerful governor of the Pskov region. According to the police investigation into the attack, the alleged organiser Alexander Gorbunov paid 3.3 million roubles ($53,000) to ex-employees of the security department of Zaslon, a company owned by Turchak’s family, to beat Kashin. Later the wife of Danila Veselov, one of the defendants, gave an interview to the Kommersant newspaper, claiming that her husband had met Turchak before the attack and had recorded the governor saying that Kashin had to be beaten so he “could not write anymore”.

After five years of investigation, in September 2015, Kashin publicly named the men who were officially accused of attempted murder. Despite evidence of the possible involvement of Turchak, who is a son of a friend of Putin, he has not been questioned about the attack.

On 3 October, Kashin posted A Letter to the Leaders of the Russian Federation on his blog. In it, Kashin wrote about his frustrations, saying: “Your will in Russia is stronger than any law, and simply obeying the law is an impossible fantasy.” The open letter accuses the government of hindering the investigation into his violent assault and ends as a strong indictment of the whole political system in Russia.

Moreover, the investigator who arrested the attackers was suspended from the case. His successor was quoted in Kashin’s letter saying: “There’s the law, but there’s also the man in charge, and the will of the boss is always stronger than any law.”

In his letter, Kashin directly accused the leaders of the country of protecting Turchak from any judicial responsibility.

“You’ve decided to side with your Governor Turchak; you’re protecting him and his gang of thugs and murderers. It would make sense for somebody like me — a victim of this gang — to be outraged about all this and tell you that it’s dishonest and unjust, but I understand that such words would only make you laugh. You have complete and absolute control over the adoption and implementation of laws in Russia, and yet you still live like criminals.”

Kashin admitted that he does not expect a fair punishment for the alleged mastermind of his beating: “I can see perfectly well that the worst thing Turchak faces now is a quiet resignation, timed long after any developments in my case. This is the only justice citizens can expect, and it means that your system isn’t capable of any kind of justice at all.”

Kashin’s case has become the symbol of impunity for attacks and murders of journalists. Hundreds of leading Russian journalists signed a petition that demands the police question Turchak. Some of them publicly boycotted a literature festival in the Pskov region, while the Kremlin and the Gorbunov’s press office remained silent.

Kashin said he wishes all journalists would boycott Turchak and continue to send requests about his role in Kashin’s case to government officials. However, that level of solidarity seems to be impossible when so much of the media is directly run by the Kremlin and do not dare to do anything without its approval, said Kashin. He also holds out no hope for support from the Russian Union of Journalists, which he describes as “a weird organization” that doesn’t function properly.

According to Glasnost Defence Foundation, over 150 journalists were killed in Russia in last 15 years. The majority of these cases remain unsolved. Those who are accused of obstruction of professional activities of journalists, rarely face a fair punishment. Between 2006-2014, only one such defendant was sentenced to jail.

The murder of Igor Domnikov, a journalist with Novaya Gazeta, in 2000 has become the first case in the history of modern Russia where the mastermind behind the killing of a journalist was officially accused. In this case, it was a former Vice-Governor of Lipetsk region Sergey Dobrovskiy. After 15 years of investigations, he was summoned to a court in April 2015, but a month later the case against him was dropped due to the statute of limitations.

Kashin said he will not be surprised if his case goes the same way. However, he stressed that the difference is that the investigators don’t need 10 years more as there is already evidence.

“We can see that the government is just not interested in punishing criminals,” Kashin said.

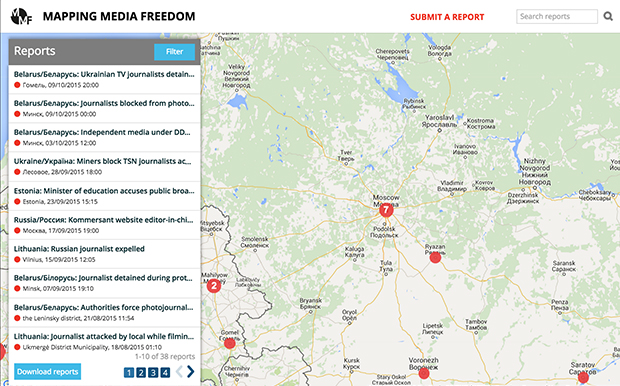

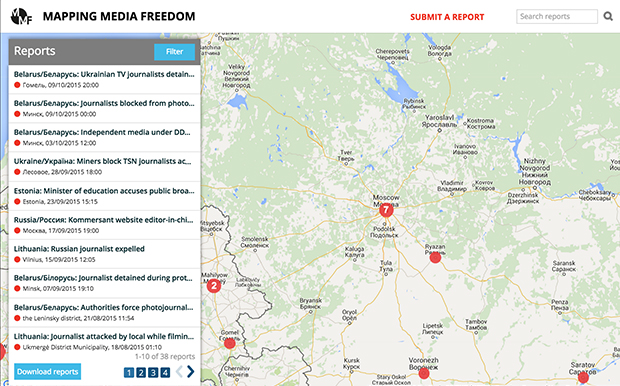

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

6 Nov 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)

People taking part in the funeral procession of murdered journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge (Photo by: Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

This would be no defence for Lasantha. President Mahinda Rajapaksa repeatedly referred to him as a “terrorist journalist” and “Kotiyek” (a Tiger).

According to exiled journalist Uvindu Kurukulasuriya, shortly before Lasantha was killed, the president offered to buy the Sunday Leader, with the intention of muting its voice. Lasantha declined the generous offer. On 8 January 2009, he was shot dead.

Days later, an astonishing editorial, written by Lasantha before his death, appeared in the Sunday Leader, and subsequently in newspapers throughout the world. After describing his pride in the Sunday Leader’s journalism, Wickrematunge wrote chillingly: “When finally I am killed, it will be the government that kills me.”

Lasantha’s murder was shocking. As was the murder of Hrant Dink, the Armenian editor who “insulted Turkishness” by daring to speak of the genocide of his people; as was the murder of Anastasia Barburova, the young Novaya Gazeta reporter who investigated the Russian far right; as was the murder of Martin O’Hagan, who took on the criminality of Northern Ireland’s loyalist gangs. As were the murders of the dozens of Filipino journalists killed in the Maguindanao massacre in 2009, too numerous to name, caught up in a ruthless turf war.

Then there are the reporters killed in war zones. The conflict in Syria has been a killing field for journalists. Where once the media were seen as protected, even potential allies, now they are seen as targets. The killings of Steven Sotloff and James Foley by ISIS in Iraq brought back memories of the beheading of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan in 2002. As Joel Simon of Committee to Protect Journalists relates in his forthcoming book, the New Censorship, that crime marked a turning point. In the Pearl case, even Osama bin Laden, who viewed the media as a potential tool in his global war, was shocked by the tactic employed by his lieutenant Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who claimed to have carried out the murder himself. From that point on, journalists were not just fair game, but trophies.

As money is drained from news, many organisations choose not to send correspondents to areas where reporters are needed most. Too dangerous, too expensive. As a result, freelancers, local journalists and fixers take ever greater risks. Under-resourced, undersupported and out on a limb, they are picked off.

Regional journalists covering tough domestic beats are easy prey. In Mexico, drug cartels boast of their ability to murder reporters. In Burma, the army kills a reporter who dares report its activities.

The numbers are horrifying: over 1,000 media workers have been killed because of their work since 1992.

Every single time, the message is sent: don’t get involved; don’t ask questions; don’t do your job. No journalism here. No inconvenient truths, no dissenting voices.

With rare exceptions, those responsible for these crimes act with impunity. Sometimes, as in the case of Anna Politkovskaya, outspoken on war crimes in Chechnya, the man who pulled the trigger is traced but those who gave the orders remain untouched. In over 90 per cent of cases of attacks on journalists, there are no convictions.

There is no greater infringement of human rights than to deliberately take an innocent life. The killing of a journalist also signals contempt for the concept of free expression as a right. As the United Nation’s Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, states, violent attacks on journalists and free expression do not happen in a vacuum: “[T]he existence of laws that curtail freedom of expression (e.g. overly restrictive defamation laws), must be addressed. The media industry also must deal with low wages and improving journalistic skills. To whatever extent possible, the public must be made aware of these challenges in the public and private spheres and the consequences from a failure to act.”

In that famous final editorial, Lasantha Wickrematunge wrote: “In the course of the last few years, the independent media have increasingly come under attack. Electronic and print institutions have been burned, bombed, sealed and coerced. Countless journalists have been harassed, threatened and killed. It has been my honour to belong to all those categories.”

Like many journalists, Lasantha prided himself on bravery: there is no higher compliment in the profession than to call a colleague “courageous”.

But there is a danger in this that we create martyrs: that we become enamoured of the idea that a good journalist should die for the cause. That persecution and suffering are marks of valour.

They are not. Journalism should be intrepid, of course, but we shouldn’t accept the idea that intrepid journalism comes with a price. Journalism, the exercise of free expression, is a basic right both for practitioners and for the readers, viewers and listeners who benifit from it. They should be able to practice this right without fear of persecution from states, criminals or terrorists. If they are to suffer, their oppressors must face justice.

Correction 10:02, 10 November: An earlier version of this article stated that a government minister offered to buy the Sunday Leader.

Index on Censorship is mapping harassment and violence against journalists across the European Union and candidate countries at mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

This article was posted on 6 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

9 Dec 2013 | News and features, Religion and Culture, Russia

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Olga Khvostunova of Interpreter Magazine reports on media ownership in Russia

Recent history of the Russian media shows how the media system was preconditioned by the country’s political development. In the 1990s the Russian media system underwent major transformations following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The media were introduced into new realities: the market economy, the end of ideological control of the Communist Party, political pluralism, the development of new public institutions, et al. Fascinated by the seemingly ideal Western model of the press, Russian media borrowed most of its characteristics: freedom of speech, private ownership of the media outlets, similar legislation, distance from the state, public influence, and a watchdog role.

Still, development of the new Russian media system in the direction of the Western ideal was constrained by the deeply rooted cultural and professional traditions of Russian journalism. “For centuries, journalism as a social institution in Russia has been developing free from economic considerations while the role of the economic regulator has been carried out by the state which in turn secured the paternalistic foundation in journalism… [In the 1990s] the state, while liberating the economic activity in the media, was not ready to relax control over the content. This has produced practically unsolvable tension for the media themselves trying to function both as commercial enterprises and as institutions of the society.” [Ivanitsky]. The role of the state in the Russian media system has been and remains dominant.

After the new Law on Mass Media was adopted in 1991, thus effectively establishing guarantees for independence of the media and the freedom of speech, the first stage of privatization of the media market followed. In the early 1990s, as the country was going through an acute financial crisis, state funding of the media was cut manifold, which, in its turn, led to drastic cuts in circulation numbers and staff. As some scholars note, a whole generation of Soviet journalists were forced to change profession. At the same time, numerous private media companies were created driven by the forces of the free market; many old media outlets were privatized, reformatted and re-purposed.

Despite the fact that Russian political and social institutions underwent major formal changes during the transition period, there was no systemic change in the informal practices. As the new elites were fighting for redistribution of power and economic wealth, the country’s transformation reminded more of the “democratic civic masquerade” [Gross] rather than presented real change. The “masquerade” could also be observed in the media system. Creation of formal procedures of interactions between the media and the state did not destroy traditional informal relations between journalists and officials.

As the country acquired relative political and economic stability by mid-90s, the second stage of the media privatization began under President’s Yeltsin “polycentric” political model. “Polycentric” model was based on the balance of various power centers—oligarchs, industrial-financial groups, and regional state administrations. During this period the media enjoyed relative freedom and independence from the state, however, the new owners and managers of the media enterprises used them quite instrumentally—to manufacture favorable public opinion. Both political and business elites saw the media as weapons to gain political capital. On various occasions, business elites would barter the loyalty of their privatized media for economic and political perks. As Boris Berezovsky, one of the owners of ORT (Public Russian Television, now renamed to Channel One) of the time acknowledged, he “never got financial profits from ORT… Political profits were endless, economic—none.” [Resnyanskaya].

During this period the struggle among the elite clans was often reflected in the media in the form of “black” and “grey” PR, and kompromat wars. The elites seemed to recognize the advantages of the media in this struggle and aspired for converting these advantages into concrete benefits and moves in the power play. But the media could provide even more leverage for political purposes. Election campaigns—national, regional and local—would be impossible to win without the support of the media. The struggle for political power culminated in 1996 presidential elections, in which the incumbent President Yeltsin went to the runoff with the leader of the Russian Communist Party Gennady Zyuganov. In this historical standoff, Yeltsin managed to win by a small margin.

Much of the credit for this victory is attributed to the new liberal Russian media outlets that actively endorsed the incumbent president, despite his health problems and a much publicized alcohol addiction. Among these media were NTV, Russia’s first independent TV-channel that was considered one of the most objective and highly professional television networks in 1994-96, and Kommersant, one of the first business dailies in Russia. At the time NTV was a part of MediaMost media holding owned by an influential Russian oligarch Vladimir Gusinsky; and Kommersant Daily belonged to another influential oligarch and advisor to President Yeltsin—Boris Berezovsky. Thus, the media played a crucial role in the drive of the public opinion in favor of Yeltsin and in his eventual victory.

The third stage of the evolution of the media system in Russia started with Vladimir Putin’s rise to power in 2000. The new Russian president transformed the country’s political system from “polycentric” to “monocentric” under the slogan of increasing stability and security—the issues that brought him substantial public support. By building the so-called “power vertical” Vladimir Putin eliminated all alternative political forces and established control over the government, the parliament, the judiciary, and the media system to secure stability of the new regime. In early 2000s various state agencies took financial or managerial control over 70 percent of electronic media outlets, 80 percent of the regional press, and 20 percent of the national press [Vartanova]. As a result, Russian media continued to be used as tools of political control but now these “tools” were no longer distributed among competing political parties and businesses, but remained concentrated in the hands of a closed political circle that swore loyalty to President Putin.

Overall, during this period the political discourse in Russia deteriorated, and the public debate in the media was either substituted by the imitative forms1 or squeezed out from the popular media outlets, such as television and dailies with large circulation, to the publications with much smaller readership, like Novaya Gazeta, or to the internet. Under the pressure from the new Kremlin’s elite, in 2001 Boris Berezovsky was forced to sell his share of ORT to Roman Abramovich, another Russian oligarch, who claimed his loyalty to Vladimir Putin. The symbolic culmination of the new elite’s war for media control was the government’s takeover of MediaMost holding (its most valuable asset was NTV) in 2002 by Gazprom Media—a subsidiary of Gazprom, the largest state-owned corporation in Russia.

At the same time, during this period, Russian media became an integral part of the global media community following the process of global convergence and homogenization. “While the media were exercising its policies to make TV less politically engaged, the advertising and media business easily filled ‘empty’ niches of political programming with entertainment content.” [Vartanova] Under the new conditions of the monocentric political system, it was a natural process: the state enjoyed the benefits of controlling the political discourse, and the media welcomed financial inflow from the booming advertising industry in Russia.

One of the key characteristics of Russia’s political system under Vladimir Putin’s rule is informal subjecting of the legislative and judicial branches of power to the executive branch, controlled by the President. This hierarchy helped the President to achieve his goal—to establish control over the entire political process, eliminate possible risks of competition, and restructure the system of checks and balances. By silencing a group of powerful non-conforming businessmen2, Vladimir Putin sent a clear message to the business community to distance themselves from politics and thus established control over corporate Russia. From now on, only those who complied with his political line and demonstrated loyalty and support were allowed to continue their business as usual.

The state learned to utilize a wide selection of political, economic and legal tools to put pressure on and intimidate the media [Vartanova]. Some of them are:

- providing personal privileges or access to closed sources of information; preferential treatment for certain media outlets and journalists;

- acquiring state ownership in media outlets or establishing indirect control through ownership by private companies whose owners are loyal to the state;

- banning access to official events and press conferences, refusal to provide requested information;

- bringing legal suits against media outlets and journalists on the grounds of defamation, libel, et al.;

- penalizing the media and suspending the license;

- using legal sanctions, such as tax or customs legislation, fire safety and sanitary regulation.

Application of these techniques transformed Russian media system into a restricted homogenous field, where only state-controlled media outlets were allowed to operate on the national scale. The regime allowed for limited operations of the independent media (the press and the internet media) to absorb the protest mood3.

Because of the constrained political environment, Russian media were unable to resist the pressure from the state and succumbed to the well-known propaganda and conformism pattern according to which they’ve been operating in the Soviet times. The period of the relative freedom of press ended with Vladimir Putin ascension to power, it was too short for the Russian media to become a strong democratic institution and a watchdog.

It is noteworthy that today’s situation differs from the Soviet times. Russia is no longer a closed country, Russian media are exposed to the free flow of information and the developments of the global media market, and Russian journalists are aware of the media’s role in the free world. Therefore, by choosing to serve as propaganda tools to receive benefits from the state, by abandoning their public duty to report the truth, the majority of the media voluntarily chose to engage in corrupt practices.

Deterioration of the public political discourse is a direct result of the lack of political pluralism and competition. As it happens in all closed regimes, political discourse in Russia transformed from an open political communication into the state’s narrative. As a result, the content of political discourse became flat and dull.

Considering general disillusionment of the Russian citizens in politics and in their own abilities to influence political process or bring about change, public interest shifted from politics to the entertainment segment, which drives the expansion of the entertainment segment. Another reason for this expansion is commercialization of the global media market driven by advertising industry and aimed at stimulating consumption. As mentioned above, the diminishing political discourse created an information vacuum in Russia that, with lack of other alternatives, had been filled with entertainment content. Eventually, this process led to tabloidization of the media and the prevail of the popular media formats that appeal primarily to the mass audience.

Russian Media MARKET and the Global Trends

The outlook of the Russian media market provides an insight into the type of information Russian media produce and the public consumes. It shows that entertainment content has filled the empty niche of the political programming. At the same time, while political and investigative journalism is declining in Russia, Russian media market is booming due to the high inflow of advertising money. Today, Russia ranks ninth in the top-10 media markets in the world, and in 2013 its market growth rate is estimated to be at 12 percent—the highest rate across the top ten media markets (see Table 1).

Table 1. Top-10 Media Markets

-

|

Ranking

(2013, est.)

|

Country

|

Growth Rate

(2012*)

|

Growth Rate

(2012**)

|

|

1

|

United States

|

+4%

|

+3%

|

|

2

|

China

|

+6%

|

+7%

|

|

3

|

Japan

|

+3%

|

+3%

|

|

4

|

United Kingdom

|

+4%

|

+3%

|

|

5

|

Germany

|

-1%

|

0%

|

|

6

|

Australia

|

-1%

|

+1%

|

|

7

|

Brazil

|

+13%

|

+9%

|

|

8

|

France

|

-4%

|

0%

|

|

9

|

Russia

|

+13%

|

+12%

|

|

10

|

Italy

|

-12%

|

-5%

|

Source: Aegis Global Report.

* Compared to 2011; ** Compared to 2012.

According to Aegis Global Report, the high growth rate of the Russian media market is driven by the growth of the advertising market, especially in the premium sector (companies with the annual advertising budget of more than 3 billion rubles, or ~$100,000). Industries, such as medicine and IT, have demonstrated the highest growth of 18 and 13 percent respectively. The 2014 Sochi Olympic Games is expected to give the market an additional boost next year.

Television

The ownership structure of the Russian media market shows that the national media outlets with the highest audience reach are controlled by the state, primarily—television.

Television in Russia is the leading source of information. 99 percent of Russian households have at least one TV-set, and about 94 percent of Russians watch TV on a daily basis [Vartanova]. The core of the TV market consists of 19 federal channels available to more than 50 percent of population. The top-five channels by the audience reach are: Perviy Kanal (Channel One), Rossiya 1, NTV, TNT and Pyatiy Kanal (Channel 5).

Russian television is a mixture of two models—one is state-controlled (major TV channels are either owned by the state or by businessmen and companies loyal to the state); the other model is purely commercial—it provides entertainment content. Regardless of the ownership structure, Russian television is mostly financed through advertising and sponsorship [Vartanova].

The chart below shows that the three main channels—Perviy Kanal (Channel One), Rossiya 1 and NTV—have the highest audience reach: 14.2 percent, 13.7 percent, and 13.5 percent respectively.

All three TV channels are controlled by the state: the majority share of Channel One belongs to Rosimuschestvo (the Federal Agency for State Property Management). Other shareholders include National Media Group (controlled by the structures of Yuri Kovalchuk, Chairman of the Board of Rossiya Bank, one of the largest banks in Russia, and Vladimir Putin’s personal friend; and Roman Abramovich, owner of Chelsea football club and Putin’s ally). Rossiya 2 is a part of VGTRK (All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company) which is owned by Rosimushchestvo. NTV is also controlled by the state through Gazprom Media. TNT and Pyatiy Kanal that come respectively fourth and fifth in the top TV channels by audience reach, are also controlled by the state. TNT belongs to Gazprom Media, while Channel 5 is controlled by National Media Group.

Top TV Channels Audience Reach, 2012-2013

Download (DOCX, 165KB)

Print Press

According to the recent Report of the Russian Guild of Press Publishers, the total circulation of print media outlets in Russia is around 7.8 billion copies, including 2.7 billion copies of national dailies, 2.6 billion—of regional copies, and 2.5 billion—of local press copies. Similar to the television segment, the press market is divided between the two media models: quality dailies and weeklies that are mostly business oriented and have relatively small readership; and popular newspapers and magazines that are inclined to tabloidization.

For the last five years, the share of print press has been steadily decreasing. In the first half of 2013, the circulation of national newspapers and magazines went down by 7.5 percent, while its market share shrank by 6 percent. The main reasons for that were the recession following the 2008 financial crisis, growth of the share of internet media, ban of advertising alcohol beverages (since January, 2013) and the expected ban of advertising tobacco products (projected to come into force in 2014). Tobacco and alcohol companies were among the major contributors in the print market profits.

The structure of the print press market is much more diverse in terms of ownership, but publications with entertainment content, glossy fashion magazines, tabloids, et al. are dominating the market.

The results of 2012 TNS survey on the audience reach of the Russian publications presented in Table 2 reveal a number of current trends: 1) the newspaper with the largest audience reach in Russia is a classified daily (Iz Ruk v Ruki); 2) it is followed by Metro—a freesheet daily intended primarily for commuters; 3) the third is Rossiyskaya Gazeta, an official source of political information provided by the state; owned by Rosimushchestvo; 4) out of top ten outlets, only two newspapers provide quality political/business content—Kommersant (8th) and Vedomosti (9th), while other newspapers cover entertainment sector.

It is noteworthy that Izvestia, a well-known, respected Soviet brand, was acquired by the National Media Group in 2011. The new owners pronounced it to become a state-controlled competitor of Kommersant and Vedomosti. Izvestia covers Russian politics, but as one of its owners and editor-in-chief Aram Gabrelyanov told in an interview,4 his newspaper has three forbidden topics: the president, the prime minister, and the patriarch. Another detail that needs to be mentioned is that even though Kommersant gained its reputation of the first independent quality daily in Russia, in 2006 it was acquired by Alisher Usmanov, head of Metallinvest Management Company. Mr Usmanov was ranked 1st in the Forbes’ Top-200 Richest Businessmen in Russia in 2013, and openly supports Vladimir Putin. In the context of the Russian political system, such ownership suggests that Kommersant’s coverage of politically sensitive issues can be managed by application of the so-called “administrative resource,” a.k.a. pressure from the Kremlin.

Table 2. Top Dailies in terms of Audience Reach* (All-Russia)

|

Newspaper |

Audience Reach (thousands of people)

|

%

|

| 1 |

Iz Ruk v Ruki (From Hand to Hand) |

3242.9

|

5.4

|

| 2 |

Metro |

1932.1

|

3.2

|

| 3 |

Rossiyskaya Gazeta |

1060.3

|

1.8

|

| 4 |

Moskovsky Komsomolets |

1048.1

|

1.7

|

| 5 |

Sport-Express |

523.9

|

0.9

|

| 6 |

Sovietsky Sport |

418.9

|

0.7

|

| 7 |

Izvestia |

334.9

|

0.6

|

| 8 |

Kommersant |

219.9

|

0.4

|

| 9 |

Trud (Labor) |

196.9

|

0.3

|

| 10 |

Vedomosti |

134.6

|

0.2

|

Source: TNS Russia, NRS, 2012

* Komsomolskaya Pravda did not participate in this survey, but according to the public data, its daily circulation is around 655,000 copies, Friday edition—2.7 million.

Table 3 provides evidence that the Russian readers lack interest in political issues. All top ten weeklies with the largest audience reach in Russia are popular publications with mass appeal (i.e. Argumenty i Fakty, Komsomolskaya Pravda, Moya Semiya) and tabloids (i.e. Zhizn, Express Gazeta). Weeklies that provide serious analysis of the current political issues are scarce on the market. Few examples are Kommersant-Vlast, Expert, and the New Times, but the first two magazines are owned by the oligarchs who openly support the President. Kommersant-Vlast is produced by Kommersant Publishing House that, as mentioned above, is owned by Alisher Usmanov. Expert is a part of Expert Media Holding that is owned by Oleg Deripaska’s Basic Element and a Russian state corporation—Vnesheconombank.

Table 3. Top Weeklies in terms of Audience Reach* (All-Russia)

|

Newspaper |

Audience Reach (thousands of people)

|

%

|

| 1 |

Argumenty i Fakty (Arguments and Facts) |

6389.3

|

10.6

|

| 2 |

Komsomolskaya Pravda |

5287.1

|

8.8

|

| 3 |

Teleprogramma |

4890.1

|

8.1

|

| 4 |

777 |

4399.0

|

7.3

|

| 5 |

Orakul (Oracle) |

2230.7

|

3.7

|

| 6 |

Moya Semiya (My Family) |

1806.0

|

3.0

|

| 7 |

Moskovsky Komsomolets (MK + TV) |

1744.6

|

2.9

|

| 8 |

Zhizn (Life) |

1710.1

|

2.8

|

| 9 |

MK Region |

1532.2

|

2.5

|

| 10 |

Express Gazeta |

1250.4

|

2.1

|

Source: TNS Russia, NRS, 2012

At the same time the audience preferences across Russia differ from those of the population of the large cities. Table 4 shows this difference for Moscow audience. Moskovsky Komsomolets is the second most popular newspaper in Moscow. Even though the newspaper has a mass media appeal and tends to tabloidization, sometimes it publishes sharp political commentaries. The newspaper is owned by its editor-in-chief Pavel Gusev, who also holds several official positions, such as head of the Moscow Union of Journalists, member of the Presidential Human Rights Council, and member of the Russian Public Chamber. Still, private ownership of the newspaper allows for certain freedom in terms of political discourse.

Another difference is that Novaya Gazeta appears eighth in the top ten most popular newspapers in Moscow. Novaya Gazeta is one of the very few newspapers on the market that produces high standard pieces of investigative journalism. It is owned by the members of the editorial board; minority shares belong to Russian businessman Alexander Lebedev and former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev.

Table 4. Top Dailies in terms of Audience Reach* (Moscow)

|

Newspaper |

Audience Reach (thousands of people)

|

%

|

| 1 |

Metro |

1164.1

|

11.6

|

| 2 |

Moskovsky Komsomolets |

685.8

|

6.8

|

| 3 |

Rossiyskaya Gazeta |

210.5

|

2.1

|

| 4 |

Sport-Express |

171.8

|

1.7

|

| 5 |

Sovietsky Sport |

167.5

|

1.7

|

| 6 |

Iz Ruk v Ruki |

138.9

|

1.4

|

| 7 |

Izvestia |

119.2

|

1.2

|

| 8 |

Novaya Gazeta |

112.1

|

1.1

|

| 9 |

Kommersant |

110.4

|

1.1

|

| 10 |

Vedomosti |

91.7

|

0.9

|

Source: TNS Russia, NRS, 2012

Radio

Radio is the growing segment of the Russian media market. According to Vartanova, the main reasons for the increase in number of the radio stations are advancements in broadcasting of commercial music, and fragmentation of the audience. Aegis Global Report shows that in 2012 radio segment of the advertising market in Russia increased by 23 percent, but in the first half of 2013 the growth slowed down to 14 percent.

The majority of the Russian radio stations broadcast music and entertainment content. According to 2012 VTsIOM survey, Russkoye Radio is the most popular radio station in Russia, followed by Europa Plus and Autoradio. Out of 15 radio stations that are listed in the ranking, only three broadcast political talk shows: Mayak, Radio Rossiya, and Ekho Moskvy. Mayak and Radio Rossiya are state-owned (Rosimushchestvo), while Ekho Moskvy is owned by Gazprom Media. Still, Ekho Mosvky allows for members of opposition to participate in some its programs and to voice criticisms of the regime.

Table 5. Most Popular Radio Stations

| # |

Radio Station |

Audience Reach

|

| 1 |

Russkoye Radio (Russian Radio) |

14%

|

| 2 |

Europa Plus |

11%

|

| 3 |

Avtoradio |

10%

|

| 4 |

Mayak |

9%

|

| 5 |

Radio Shanson |

8%

|

| 6 |

Radio Rossiya |

7%

|

| 7 |

Dorozhnoye Radio (Road Radio) |

5%

|

| 8 |

Radio Dacha |

4%

|

| 8 |

Retro FM |

4%

|

| 9 |

Hit FM |

3%

|

| 9 |

Dynamite FM |

3%

|

| 9 |

Yumor FM (Humor FM) |

3%

|

| 10 |

Ekho Moskvy |

2%

|

| 10 |

Love Radio |

2%

|

| 10 |

Militseyskaya Volna (Police Wave) |

2%

|

Source: WTsIOM, 2012

Internet

Internet market in Russia shows extremely positive dynamic. In the first half of 2013, internet advertising grew by 30 percent, which is the highest increase across all media.

As the chart below shows, the increase of the internet share has been quite dramatic. In 2007, the share of internet of the Russian media market did not exceed 3 percent, while by 2012 it has amounted to 19 percent. Over the same period, the share of the print press dropped by 9 percent, and radio—by 3 percent, while the share of television decreased by 1 percent.

Structural Change of the Russian Media Market (market percentage)

Source: Aegis Global Report.

However, it’s noteworthy that the share of internet grows not only because new users acquire access to the internet, but also because of the increase in the number of connection points. Today, every fourth internet user in Russia has three or more devices connecting them to the internet. Meanwhile, the number of Russian citizen who have access to internet hardly exceeds 50 percent5. But as shown at the chart below, the average daily reach of popular Russian internet resources (Yandex, Mail.ru, Vk.com) is actually higher than that of Perviy Kanal.

Source: Aegis Global Report

Table 6 shows the most popular websites of the Russian internet (RuNet) by their audience reach. Yandex tops the list, being the most popular Russian search engine and accumulating 34 websites on its platform. Yandex’s primary competitor Mail.ru comes third, but two other websites of the Mail.ru Group (odnoklassniki.ru and Moi Mir) are rated fifth and sixth.

Popular internet media (as opposed to internet search engines and social media) are at the bottom of the Top-15 list. Rbc.ru and Qip.ru belong to a privately owned RBC Holding, while Ria.ru is an internet platform of RIA Novosti, a state-owned news agency. Kp.ru is a part of Komsomolskaya Pravda Holding is owned by ESN Group, associated with a state transportation company—Russian Railways.

Table 6. RuNet’s Most Popular Internet Websites

|

Website |

Operator |

Monthly Audience Reach* (thousands visits) |

| 1 |

Yandex.ru |

Yandex |

29166.2

|

| 2 |

Vk.com |

VKontakte |

29143.3

|

| 3 |

Mail.ru |

Mail.ru Group |

27065.2

|

| 4 |

Google (ru + com) |

Google |

26036.4

|

| 5 |

Odnoklassniki.ru |

Mail.ru Group |

25264.9

|

| 6 |

Moi Mir (my.mail.ru) |

Mail.ru Group |

22830.5

|

| 7 |

LiveJournal.com |

SUP Media |

16139.4

|

| 8 |

Rutube.com |

RuTube |

15096.5

|

| 9 |

Avito.ru |

AVITO |

14552.8

|

| 10 |

Liveinternet.ru |

Klimenko & Co |

11290.8

|

| 11 |

Kinipoisk.ru |

Kinopoisk |

10634.3

|

| 12 |

Rbc.ru |

RBC Holding |

9995.7

|

| 13 |

Qip.ru |

RBC Holding |

9709.4

|

| 14 |

Ria.ru |

RIA Novosti |

9106.6

|

| 15 |

Kp.ru |

Komsomolskaya Pravda |

8823.7

|

Sources: TNS, Tasscom, March 2012

Today, Russian internet is quite diverse in terms of forms of ownership, which allows for greater freedom of expression and variety of information sources.

This article was originally posted on 6 Dec 2013 at interpretermag.com and is reposted here with permission.

Footnotes:

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)