Russia: editor beaten

Yet another journalist has been brutally attacked in Russia. Maria Eismont reports

Yet another journalist has been brutally attacked in Russia. Maria Eismont reports

(more…)

Yet another journalist has been brutally attacked in Russia. Maria Eismont reports

Yet another journalist has been brutally attacked in Russia. Maria Eismont reports

(more…)

Mikhail Viktorovich Feigelman started working at the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics in Moscow in 1980. Eleven years later, when the Soviet Union collapsed, funding and decent modern equipment were rare for Russian scientists but there was suddenly intellectual freedom.

“This is why I stayed in Russia at this time, despite the hardships,” the 70-year-old physicist told Index. “This freedom during the 1990s was very important, but it didn’t last long.”

In May 2022, just months after Russian President Vladimir Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Feigelman fled to western Europe.

“I left exclusively because of the war,” he said. “I could no longer live in Russia anymore, where I see many parallels with Nazi Germany. I will not return home until the death of Putin.”

Initially, Feigelman took up a position at a research laboratory in Grenoble, France, where he stayed for a year and a half. Today, he is employed as a researcher at Nanocenter in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“I have not experienced any prejudice or discrimination in either France or Slovenia,” he said.

“But in Germany – at least in some institutions – there is a [ban] on Russian scientists, and it is forbidden to invite them for official scientific visits.”

These measures stem from a decision taken by the European Commission in April 2022 to suspend all co-operation with Russian entities in research, science and innovation.

That included the cutting of all funding that was previously supplied to Russian science organisations under the EU’s €95.5 billon research and innovation funding programme, Horizon Europe.

The boycotting had already begun elsewhere. In late February 2022, the Journal of Molecular Structure, a Netherlands-based peer-reviewed journal that specialises in chemistry, decided not to consider any manuscripts authored by scientists working at Russian Federation institutions.

One former employee at the journal, who wished to remain anonymous, said Russian scientists were always welcomed to publish in the journal. “A decision had been taken, for humanitarian reasons, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, not to accept any submission authored by scientists (whatever their nationality) working for Russian institutions,” they said.

Last January, Christian Jelsch became the journal’s editor. “This policy to ban Russian manuscripts was implemented by the previous editor,” he said. “But it was terminated when I started as editor.”

Feigelman believes all steps taken “to prevent institutional co-operation between Europe and Russia are completely correct and necessary.”

But he added: “Contact from European scientists with individual scientists must be continued, as long as those scientists in question are not supporters of Putin.”

Alexandra Borissova Saleh does not share that view.

“Boycotts in science don’t work,” she said. “There is a vast literature out there on this topic.”

She was previously head of communication at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology and head of the science desk at Tass News Agency in Moscow.

Today, Borissova Saleh lives in Italy, where she works as a freelance science journalist and media marketing consultant. She has not returned to Russia since 2019, mainly because of how scientists are now treated there.

“If you are a top researcher in Russia who has presented your work abroad, you could likely face a long-term prison sentence, which ultimately could cost you your life,” she said.

“But the main reason I have not returned to Russia in five years is because of the country’s ‘undesirable organisations’ law.”

First passed in 2015 – and recently updated with even harsher measures – the law states that any organisations in Russia whose activities “pose a threat to the foundations of the constitutional order, defence or security of the state” are liable to be fined or their members can face up to six years in prison. This past July,

The Moscow Times, an independent English-language and Russian-language online newspaper, was declared undesirable by the authorities in Moscow.

“I’m now classed as a criminal because of science articles I published in Russia and in other media outlets,” Borissova Saleh explained.

Shortly after Putin invaded Ukraine, an estimated 7,000 Russian scientists, mathematicians and academics signed an open letter to the Russian president, voicing their public opposition to the war.

According to analysis carried out by the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, since February 2022 at least 2,500 Russian scientists have left and severed ties with Russia.

Lyubov Borusyak, a professor and leading researcher of the Laboratory of Socio-Cultural Educational Practices at Moscow City University, carried out a detailed study of Russian academics included in that mass exodus.

Most people she interviewed worked in liberal arts, humanities and mathematics. A large bulk of them fled to the USA and others took up academic positions in countries including Germany, France, Israel, the Netherlands and Lithuania. A common obstacle many faced was their Russian passport.

It’s a bureaucratic nightmare for receiving a working and living visa, Borusyak explained.

“Most of these Russian exiles abroad have taken up positions in universities that are at a lower level than they would have had in Russia, and quite a few of them have been denied the right to participate in scientific conferences and publish in international scientific journals.”

She said personal safety for academics, especially those with liberal views, is a definite concern in Russia today, where even moderate, reasonable behaviour can be deemed as extremist and a threat to national security.

“I feel anxious,” she said. “There are risks and I’m afraid they are serious.”

Hannes Jung, a retired German physicist believes it’s imperative scientists do not detach themselves from matters of politics, but that scientists should stay neutral when they are doing science.

Jung is a prominent activist and co-ordinator for Science4Peace – a cohort of scientists working in particle physics at institutions across Europe. He said their aim was “to create a forum that promotes scientific collaboration across the world as a driver for peace”.

He helped form Science4Peace shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, as he felt the West’s decision to completely sever ties with Russian scientists was counterproductive and unnecessary.

“At [German science research centre] Desy, where I previously worked, all communication channels were cut, and we were not allowed to send emails from Desy accounts to Russian colleagues,” said Jung. “Common publications and common conferences with Russian scientists were strictly forbidden, too.”

He cited various examples of scientists working together, even when their respective governments had ongoing political tensions, and, in some instances, military conflicts. Among them is the Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (Sesame) in Jordan: an inter-governmental research centre that brings together many countries in the Middle East.

“The Sesame project gets people from Palestine, Israel and Iran working together,” Jung said.

The German physicist learned about the benefits of international co-operation among scientists during the hot years of the Cold War.

In 1983, when still a West German citizen, he started working for Cern, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Based on the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva, the inter-governmental organisation, which was founded in 1954, operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. At Cern, Jung was introduced to scientists from the German Democratic Republic, Poland and the Soviet Union. “[In] the Soviet Union the method for studying and researching physics was done in a very different way from in the West, so there was much you could learn about by interacting with Soviet scientists,” he said.

In December 2023, the council of Cern, which currently has 22 member states, officially announced that it was ending co-operation with Russia and Belarus as a response to the “continuing illegal military invasion of Ukraine”.

Jung believes Cern’s co-operation with Russian and Belarussian scientists should have continued, saying there was no security risk for Cern members working with scientists from Belarus and Russia.

“There is a very clear statement in Cern’s constitution, explaining how every piece of scientific research carried out at the organisation has no connection for science that can be used for military [purposes],” he said.

In June, the Cern council announced it would, however, keep its ongoing co-operation with the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR), located in Dubna, near Moscow.

“I hope Cern will continue to keep these channels open to reduce the risk for nuclear war happening,” said Jung.

Can cultural and academic boycotts work to influence social and political change? Sometimes.

They seemed to play a role, for example, in the breakup of apartheid South Africa (1948 to 1994). This topic was addressed in a paper published in science journal Nature in June 2022, by Michael D Gordin.

The American historian of science argued that for science sanctions to work – or to help produce a change of mindset in the regime – the political leadership of the country being sanctioned has to care about scientists and science. “And Russia does not seem to care,” Gordin wrote.

His article pointed to the limited investments in scientific research in Russia over the past decade; the chasing after status and rankings rather than improving fundamentals; the lacklustre response to Covid-19; and the designation of various scientific collaborations and NGOs as “foreign agents”, which have almost all been kicked off Russian soil.

Indeed, Putin’s contempt and suspicion of international scientific standards fits with his strongman theory of politics. But such nationalist propaganda will ultimately weaken Russia’s position in the ranking of world science.

Borissova Saleh said trying to create science in isolation was next to impossible.

“Science that is not international cannot and will not work. Soviet science was international and Soviet scientists were going to international scientific conferences, even if they were accompanied by the KGB,” she said.

Sanctioning Russian scientists will undoubtedly damage Russian science in the long term, but it’s unlikely to alter Russia’s present political reality.

Authoritarian regimes, after all, care about only their own personal survival.

Last week’s mutiny by Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the mercenary Wagner Group, provided a challenge to established western media outlets, such was the speed of the advance by the man known as Putin’s chef towards Moscow and the lack of verifiable information coming out of Russia. The subsequent accommodation between Prigozhin and Putin, apparently brokered by the Belarus leader Alyaksandr Lukashenska, has left even the most seasoned neo-Kremlinologists scratching their heads.

Step forward the Russian dissidents and independent news services. Index has been privileged to work with the opposition to Putin since long before the war in Ukraine and it was good to see them coming into their own last week. Here are some of our recommendations for those who want to stay abreast of the fast-moving and often baffling developments in Russia. Kevin Rothrock (@KevinRothrock), the managing editor of the English-language version of the independent online site Meduza, kept his Twitter feed consistently updated during the coup-that-never-was. Where others were breathless and over-excited, Rothrock was calm and measured. His colleague Lilya Yapparova (@lilia_yapparova) provided detailed analysis on the future of Prigozhin from sources inside the Russian military and the Wagner Group itself. Yapparova’s far-reaching investigation looks into what Wagner forces might contribute to Belarusian military capacity and the organisation’s operations in Africa and Syria. She also looks into Wagner’s finances in Russia, its continued recruitment for the war in Ukraine and internet trolling operations. Yapporova quotes the work of Dossier Center, a media outlet connected to the British-based Putin opponent Mikhail Khodorkovsksy, which tracks criminals associated with the Russian president. Khodorkovsky himself was active on his Telegram channel throughout the mutiny and accessible to non-Russian speakers through the messaging app’s translate function. Controversially he urged Russians to support Prigozhin’s coup. His view was that anything would be better than Putin. The Russian billionaire later concluded that the outcome of Prigozhin’s operation was not important. “The very fact that this happened is a powerful blow to Putin after which he will be perceived differently by millions.”

Doxa, the publication founded by students opposed by Putin and now outlawed by the regime, continues to do a good job of aggregating news from reliable sources. This week it included a report from The Bell, founded by Russian financial journalist Elizaveta Osetinskaya, suggesting that Prigozhin’s troll factory companies have been paralysed following raids after the uprising and were looking for a new owner. Osetinskaya, a former editor of Russian Forbes magazine, was declared a foreign agent after condemning the invasion of Ukraine.

In a new development this week, Novaya Gazeta, the independent Russian news outlet whose editor Dmitry Muratov won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021, was put on the Kremlin’s list of “undesirable” organisations. This makes it a crime for the publication, now based in Latvia, to operate in Russia. It is also now illegal for Russians to engage with the publication or share its content online.

OVD-Info, the human rights project which won the 2022 Index on Censorship campaigning award, decided not to provide a running commentary of events and stuck to its mission of reporting on arrests of regime opponents. In his weekly newsletter Dan Storyev, English editor of OVD-Info, wrote: “Russia has had a busy few days as I am sure we all know. This newsletter is not for military analysis so I won’t cover Prigozhin’s manoeuvres here — but it’s important to remember, that in the end, it is going to be ordinary Russians, Russian civil society who would bear the brunt of any violence that a coup, or a paranoid preventive crackdown could unleash.”

If there is one thing that unites all the outlets mentioned here (beyond their undoubted courage), it is the care they take in the sourcing of all information they publish. In the post-truth world of Putin’s Russia, facts are precious commodities.

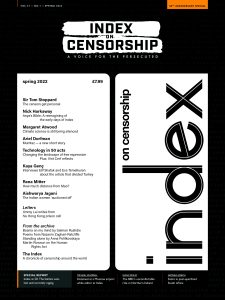

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.

This article first appeared in our Spring 2022 issue, available by print subscription here and by digital subscription here.

This article first appeared in our Spring 2022 issue, available by print subscription here and by digital subscription here.