13 Jan 2015 | News, United Kingdom

Nadhim Zahawi is a member of the BIS Select Committee, the Party’s Policy Board and MP for Stratford on Avon. This article is from Conservative Home

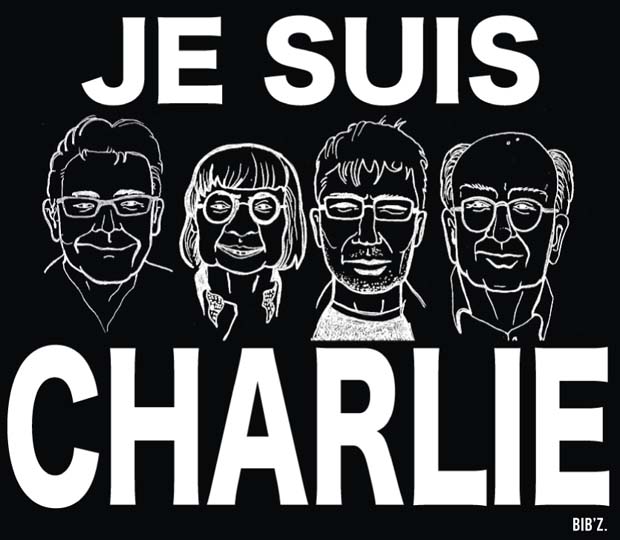

You can’t kill an idea by killing people. The sickening attack on Charlie Hebdo has shown that to be true. As France mourns her dead, millions around the world are discovering the work of her bravest satirists. Nous sommes Charlie.

Unfortunately, the same is true of the terrorists. Bin Laden may be at the bottom of the sea, but his poisonous ideology lives on. As long as it inspires deluded young men to kill, these attacks will keep happening. We can’t win this fight unless we also win the battle of ideas.

This is an urgent task. Thousands of EU citizens have travelled to the Middle East to serve under ISIS’s black banner. Many will return with combat experience and carrying the virus of radicalism. Some will be eager to put their new terrorist skills to work. It’s vital that we stop them.

Our security services have an important role to play, but research suggests that the most effective way of tackling terrorism is “changing the narrative”. That means challenging the stories used by extremists to justify their twisted worldview.

First and foremost, this means rejecting the idea that this this is a clash of civilizations: Islam versus the West. The reality is that jihadists have claimed more lives in the Islamic world than anywhere else. In December last year, the Pakistani Taliban gunned down 132 schoolchildren in their classrooms. On the same day as the attack in Paris, a car bomb exploded in Yemen killing at least 38 people. Muslim-majority countries, as much as the West, have a clear interest in stamping out this ideology.

It’s time the Islamic world took a leadership position on this issue. When the news from Paris broke, countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Afghanistan were quick to condemn the attacks. Yet all three have legal systems carrying the death penalty for blasphemy. In virtually every Muslim-majority country, publishing a magazine like Charlie Hebdo would earn you a fine or imprisonment.

These laws support the idea that religious offence is a crime to be punished rather than a price we must pay for freedom of expression. They also fuel extremist violence. In Pakistan, blasphemy charges are often levied at religious minorities on the flimsiest of pretexts. Those accused are sometimes lynched by vigilante mobs while awaiting trial. Politicians who’ve dared to speak out against the laws have been assassinated.

One of the best tributes we could pay to the brave men and women of Charlie Hebdo would be to use our diplomatic influence to get some of these laws repealed. Change won’t happen overnight, and we will have to be patient with these countries. After all, the last successful prosecution for blasphemy in Britain was as recent as 1977, and the laws only came off the statute books in 2008.

I am not arguing that we should preach to Islamic governments; but nor should we turn a blind eye to this issue. Reforming attitudes to blasphemy would send a powerful message to extremists: freedom of speech isn’t just a Western value – it’s our common birthright as human beings.

And we shouldn’t be frightened of having a conversation about religion here at home. Talking about religion doesn’t come naturally. As a culture, we ‘don’t do God’. Yet it’s vital that mainstream Muslims feel comfortable discussing their faith in public. They, not the Government, are best placed to take on the dodgy imams and self-appointed sheikhs in open debate.

The Qur’an is clear that it’s the role of Allah, not man to judge unbelievers. In the 7th Century, Ali bin Abi Talib, the cousin of the Prophet and a leader of the original Islamic Caliphate, said: “Whoever does not accept others’ opinions will perish”. There’s a sound Islamic case for freedom of expression, and it needs a good airing.

Last, we have to practice what we preach. If we want Muslims to come out and say “not in my name” every time there’s a terrorist atrocity we too need to be vocal in our condemnation of attacks on Muslims and mosques in the West.

Charlie Hebdo was a target because humour is dangerous. You can’t be the all-powerful Islamic Caliphate and be the butt of someone else’s joke. The goal of terrorism is to frighten us – so laughter is one of our most powerful weapons.

This article was originally posted at Conservative Home on January 12, 2015. It is reposted here with permission.

15 Dec 2014 | About Index, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Religious freedom and religious radicalism which leads to extremism has become an increasingly difficult balancing act in the digital age where presenting religious superiority through fear and “terror” is possible both locally and internationally at internet speeds.

The ongoing series of beheading videos released by the Islamic State and the showcase of kidnapped school girls by Nigeria’s Boko Haram on YouTube are both examples that test the extent to which the UN Convention of Human Rights can protect religious freedoms. According to a report by the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Egypt’s Youth Ministry are targeting young atheists vocal on social media about the dangers of religion. In Saudi Arabia, Raef Badawi was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2013 and received 600 lashes for discussing other versions of Islam, besides Wahhabism, online.

Article 18 of the Convention states that the “right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance”. The interpretation of “practice” is a grey area – especially when the idea of violence as a form of punishment can be understood differently across various cultures. Is it right to criticise societies operating under Sharia law that include amputation as punishment, ‘hadd’ offences that include theft, and stoning for committing adultery?

Religious extremism should not only be questioned under the categories of violence or social unrest. Earlier this month, religious preservation in India has led to the banning of a Bollywood film scene deemed ‘un-Islamic’ in values. The actress in question was from Pakistan, and sentenced to 26 years in prison for acting out a marriage scene depicting the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. In Russia, the state has banned the publication of Jehovah’s Witness material as the views are considered extremist.

In an environment where religious freedom is tested under different laws and cultures, where do you draw the line on international grounds to foster positive forms of belief?

This article was posted on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Oct 2014

5 awards. 16 years. Champions against censorship.

The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those individuals and groups making the greatest impact in tackling censorship worldwide. Established 16 years ago, the awards shine a light on work being undertaken in defence of free expression globally. All too often these stories go unnoticed or are ignored by the mainstream press.

Each year, the awards call attention to some of the bravest journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders in the world. The 2015 awards were no exception. We honoured Amran Abdundi, a Kenyan activist who has worked through various channels to support women who are vulnerable to rape, female circumcision and murder in northeastern Kenya. We also gave awards to Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who continues to make music about endemic corruption and widespread poverty in his country despite censorship being imprisoned three times; Tamás Bodoky, a journalist campaigning for a free press in Hungary; Rafael Marques de Morais, who has exposed government and industry corruption in Angola; and Safa Al Ahmad, a journalist who has spent three years covertly filming a mass uprising in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province that had, until her film, gone largely unreported.

The Freedom of Expression Awards grew naturally from the principles established by our founder, the poet Stephen Spender, who sought to give a voice to those facing censorship behind the Iron Curtain and beyond. Index had long championed writers and artists fighting threats to free expression by publishing their work in our magazine, or through our own reporting. Recognising their work through our Freedom of Expression Awards was a natural next step.

In Azerbaijan, where I have come from, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life.

That is the price that my colleagues in Azerbaijan are paying for the right of the Azerbaijani people to know the truth about what is happening in their country.

For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families.

But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.”

— Idrak Abbasov, Award winner, 2012

Who is eligible

Anyone involved in tackling free expression threats – either through journalism, advocacy, arts or using digital techniques – is eligible for the awards. Index invites nominations from the public via its website and through social media platforms. Other non-governmental organisations are also invited to suggest nominees, and individuals and groups can also self-nominate. There is no cost to applying.

We shortlist on the basis of those who are deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area, with a particular focus on those who are tackling topics that are little covered or tackled by others, or who are using innovative methods to fight censorship.

Nominations are now closed. The shortlist will be announced on 27 January 2015.

The categories?

Advocacy – recognises campaigners and activists who have fought censorship and challenge political repression. This award is sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers.

Arts – recognises artists and producers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles repression and injustice.

Digital Activism – recognises innovative uses of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate. This award is sponsored by Google.

Journalism – for impactful, original, unwavering investigative journalism across all media. This award is sponsored by The Guardian.

The judges

Each year Index recruits an independent panel of judges with expertise in advocacy, arts, journalism and human rights to work on the shortlisting of nominees. This year’s judges include journalist and campaigner Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Keir Starmer. Previous judges include playwright Howard Brenton, philanthropist Sigrid Rausing, and broadcaster Samira Ahmed.

The timeline

Nominations opened on October 14 and remained open until November 20, 2014. Nominations are now closed. The nominee shortlist will be announced on January 27. Judges make their final awards selection in February. The Digital Advocacy winner is decided by public vote. The winners of the awards will be announced at the 2015 Index Freedom of Expression Awards on March 18.

14 May 2014 | Middle East and North Africa, News, Yemen

American journalist Adam Baron in jail. He was deported from Yemen last week. (Image: @almuslimi/Twitter)

Working in Yemen as a journalist can often feel like being an involuntary character in a clichéd Hollywood drama — a hybrid of a John le Carré novel and a Johnny English-style parody.

In over three and half years living in Yemen I’ve gone on the run from government agencies on four occasions. Looking back months later you either laugh or shake your head in despair at the surreal madness of it all.

One occasion involved a more than six-hour drive across part of rural Yemen popular for US drone strikes, with a local journalist alongside me. Exhausted and relieved, our successful getaway ended just before dawn.

Another was, in hindsight, rather more comical. As Yemen’s uprising intensified in April 2011, district security chief came knocking on the door in the middle of the night. He was looking for journalists and demanded copies of foreigners’ passports. It was a few weeks after soldiers had stormed the house of three foreign journalists who were then deported. The young, clandestine-revolutionary who guarded the apartment block where American journalist Jeb Boone and I were temporarily staying, managed to put the official off until the next day.

Under the cover of darkness we each packed a small rucksack of essentials: cameras, notebooks, and a change of clothes, while planning our escape to a friend’s house which had been left empty following the evacuation of the majority of the ex-pat community due to deteriorating security in Sana’a. As we made our furtive escape, creeping out of the gate in the early hours of the morning we walked straight into a truck full of soldiers parked outside the next-door neighbour’s gate. George Smiley wept.

The third almost ended in disaster. After writing a piece in January last year for The Times on Saudi Arabia’s involvement in America’s covert war in Yemen, on advice, I once again temporarily relocated in Sana’a amid fear of reprisals for my reporting. A couple of weeks after returning to my Old City home the taxi I was travelling in was ambushed outside the Ministry of Defence. A bullet smashed through the window next to my head, hissed through the hair of my driver but miraculously left both of us unharmed. Since then I have probably become the only woman in the world to convert their United Nude shoe bag into a gunshot trauma kit which I’ve since carried with me at all times.

But, as foreign journalists we have little if anything to fear. The worst that’s likely to happen to us, as American journalist Adam Baron found out during his deportation last week, is a 10-hour spell in jail wondering if we’re going to be given a few minutes to pack before being kicked out of the country we call home, without the possibility to return.

While we — the handful of foreign journalists based in Yemen — might have anxious moments once or twice a year, our Yemeni colleagues are constantly under threat. Yemen remains amongst the bottom 15 countries out of 180 in the world for press freedom. A Human Rights Watch report last September concluded that freedom of expression since President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi took power in February 2012 has increased, but along with it, intimidation and violence against journalists has also risen. Yemen’s Freedom Foundation recorded 282 attacks and threats against journalists and media workers in 2013.

While Adam waited anxiously in jail last Tuesday, passport and phone confiscated, unease spread. Officials indicated that “other foreign journalists were next” my name was also mentioned. Not knowing if they’re coming to get you today, tomorrow, or at all, means that despite the relatively benign consequences, you are gripped with an almost unbearable sense of apprehension. Preparing for the worst I informed my editor at The Times in London and started to pack.

Three days later, still waiting, the madness felt like it was closing in. As the sunset over Sana’a on Friday evening one friend called to tell of gunfire and explosions next to his house. Meanwhile I sat in the protective darkness of my stairwell whispering into my phone as I heard the distant voices of two men banging on my front gate. Was this it? Was this the moment I would be forced to leave? My phone — on silent in case it was heard by those outside — lit up. Another friend had just narrowly avoided driving straight into a running gun battle in the south of the city. I tiptoed down the stairs in the dark and silently slid the two deadbolts across the large wooden door of the ancient Yemeni tower-house that is my home.

The irony is that while the ex-pat community goes into week two of lockdown in Sana’a and Western embassies close to the public due the increasing threat from al-Qaeda attacks, the most persistent threat to journalists on a daily basis is from the government and its intelligence agencies, not so-called militants.

After Adam was deported last week, for the first time, I decided not to run as I have too many times in the past. Without stopping and challenging what the government has done means the persecution of journalists will continue unabated.

There are just a small handful of foreign reporters based full-time in Yemen. Adam and I were the only ones accredited in a country where the government makes it almost impossible to live permanently as a foreign journalist with the correct paper work. Deporting unregistered journalists means no complaints can be made when individuals are thrown out.

As a legally operating reporter I had firm ground to stand on to support Adam and raise questions about why the government has chosen this moment to target him, and possibly me. Was this a personal vendetta against him? Or, was this a concerted effort by the state to remove witnesses? Those who may witness the consequences of a US-backed war currently being waged in the most significant military crackdown against al-Qaeda every carried out in Yemen.

The answers to those questions were partly answered by the manager of immigration who pulled me aside at Sana’a airport on Monday morning when I chose to leave Yemen of my own accord. I realised I’d had enough of the constant cycle of farcical drama, instigated by the state, that comes with living as a journalist in Yemen over three and a half years. I wanted it to stop. To take back control.

Despite the fact that my journalist visa is valid until February 2015, the immigration official began with “you can’t come back…” and ended with “it’s OK, you are allowed to leave now”. For the latter at least I was grateful.

The foreign media may not be welcome in Yemen, but if they are quietly trying to remove us then the greatest threat to be faced will be to domestic reporters. Over a snack of traditional sweet kataif pancakes and chilled apricot juice on my last day in Sana’a on Sunday, I sat with a Yemeni friend and fellow journalist. He acknowledge the need to step back from the madness. “The national security, they get to you,” he said tapping a finger against the side of his head. “You need to go home for some quiet time,” he added. “I got my quiet time…in prison.”

This article was posted on May 14, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org