17 Jun 2015 | Azerbaijan News, mobile, News and features

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

1) Azerbaijan: “incitement to suicide”

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

2) Belarus: participation in “mass disturbance”

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

3) China: “inciting subversion of state power”

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

4) Angola: “malicious prosecution”

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

5) Kuwait: “insulting the prince and his powers”

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

6) Bahrain: “misusing social media

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

7) Saudi Arabia: “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

8) Guatemala: causing “financial panic”

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

9) Swaziland: “scandalising the judiciary”

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

10) Uzbekistan: “damaging the country’s image”

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

11) Sudan: “waging war against the state”

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

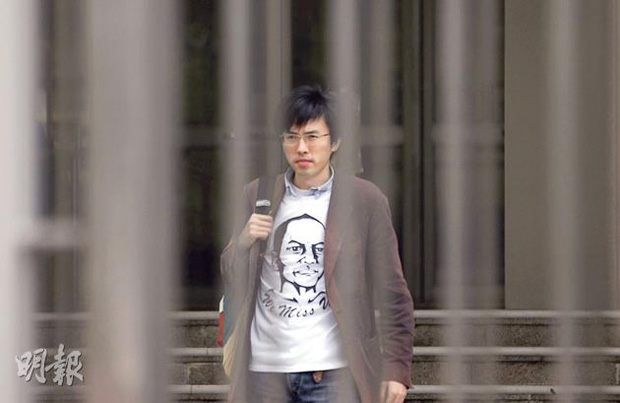

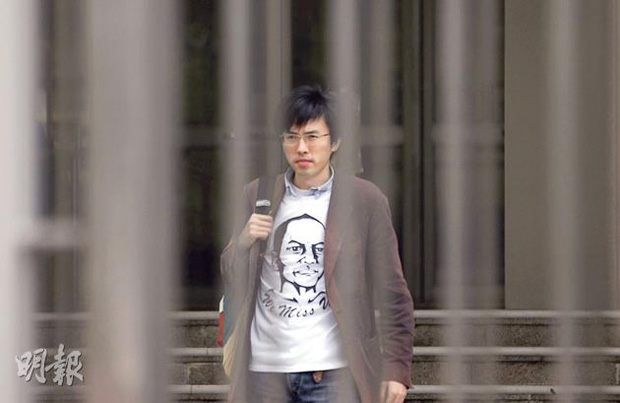

12) Hong Kong: “nuisance crimes committed in a public place”

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

13) Morocco: compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Mar 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”How can more refugees get their voices heard? The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine is out now and features a special focus on the threats to free expression within refugee camps.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

We follow the steps of Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti, who spent four years undercover investigating migrant routes from Africa to Europe. We look at how social media has become a blessing and a curse – offering a connection back home and a means of surveillance. We have pieces by refugees, written from inside camps about persisting myths; by those struggling to claim rights as workers; and by those who have set up innovative, creative projects to share their stories.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”64776″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

The issue also features a thoughtful analysis of the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, with contributions from Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman; Irish co-creator of Father Ted, Arthur Mathews; Turkish novelist Elif Shafak; British playwright David Edgar; former head of BBC news Richard Sambrook; and Hong Kong-based journalist Hannah Leung. Taking the long view, this group of writers looks at the worldwide picture, and how terror is used to silence.

Also, Martha Lane Fox and retired Major General Tim Cross go head-to-head, debating if privacy is more vital than national security. We have stories about attacks on journalists covering the drug trade in South America; a cover-up of abortion figures in Nicaragua; and the lessons to be learnt from attempts to downplay epidemics, from Aids to ebola. Plus an extract from Lucien Bourjeily’s new play, which has skirted the Lebanese censors’ ban, and poetry from Turkish writers Ömer Erdem and Nilay Özer – all translated into English for the first time.

The issue’s cover artwork is by cartoonist Ben Jennings, and the magazine also features work from our regular collaborator Martin Rowson; and extracts from a graphic reportage set in an Iraqi camp, by Olivier Kugler.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: ACROSS THE WIRES” css=”.vc_custom_1483457468599{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

How refugee stories get told

Undercover immigrant – Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti spent four years undercover investigating refugee routes from Africa to Europe

Taking control of the camera – Almir Koldzic and Aine O’Brien on refugee camp projects – from soap operas to photography classes – that help refugees tell their own stories. Also: Valentino Achak Deng on life after fleeing Sudan’s civil war; Kate Maltby visits the Syrian Trojan Women’s acting project; and Preti Taneja on bringing Shakespeare to the children of Zaatari

The way I see it – Refugees Rana Moneim and Mohammed Maarouf share their viewpoints from inside a camp, plus a camp visitor shatters his preconceptions

Clear connections – Jason DaPonte on how social media’s power is being harnessed by refugees

Who tells the stories? – Mary Mitchell and Mohammed Al Assad on a storytelling project in a Lebanon camp

Realities of the promised land – Iara Beekma looks at life for Haitian immigrants in Brazil and their rights as workers

The whole picture – Photojournalist Chris Steele-Perkins’ honest account of decades spent capturing refugees’ stories, from Rwandans to the Rohingha

Stripsearch – Our regular cartoonist, Martin Rowson, imagines the Democratic Republic of Cyberspace

Escape from Eritrea – Ismail Einashe explores the dangers of fleeing one of the world’s harshest regimes

A very human picture – Artist Olivier Kugler illustrates life within Iraq’s Domiz refugee camp

In limbo in world’s oldest refugee camps – Tim Finch looks at the places where 10 million people can spend years, or even decades

Sound and fury – Rachael Jolley interviews musician Martyn Ware, from Heaven 17 and the Human League, on the power of soundscape storytelling

Sheltering against resentment – Natasha Joseph reports from Johannesburg on the end of the line for a sanctuary for those fleeing xenophobia

Understanding how language matters – Kao Kalia Yang recalls her childhood as a Hmong refugee in Thailand and the USA

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Outbreaks under wraps – Alan Maryon-Davis looks at how denials and cover-ups spread ebola, Sars and Aids

Trade secrets – César Muñoz Acebes investigates Paraguay’s drug war and the dangers for journalists, plus Duncan Tucker on Mexico’s courageous bloggers and social media users, who are filling the gaps where Mexico’s press fears to tread

Lies and statistics – Nina Lakhani reports from Nicaragua on the cover-up of abortion figures and domestic abuse

Charlie Hebdo: taking the long view – After the Paris murders, seven writers from around the world look at how offence and terror are used to silence, featuring Arthur Mathews, Ariel Dorfman, David Edgar, Elif Shafak, Hannah Leung, Raymond Louw, Richard Sambrook

Screened shots – Jemimah Steinfeld on the Chinese film industry’s obsession with portraying Japan’s invasion during World War II

Finland of the free – Risto Uimonen explains why the Finns always top media freedom indexes, and the Belfast Telegraph’s readers’ editor, Paul Connolly, shares his thoughts on the future of press regulation

Head to head: Is privacy more vital than national security? Martha Lane Fox and Tim Cross debate how far governments should go when balancing individual rights and safeguarding the nation

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The state v the poets – Kaya Genç introduces works by Turkish poets Ömer Erdem and Nilay Özer

Knife edge – Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily presents an exclusive extract from his latest play as it escapes the censors’ ban

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg says universities must not fear offence and controversy

Index around the world – Aimée Hamilton provides an update on Index on Censorship’s work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Social disturbance – Vicky Baker looks at how user-generated content lost its innocence, from digital jihadis to hoaxes and propaganda

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Jun 2014 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

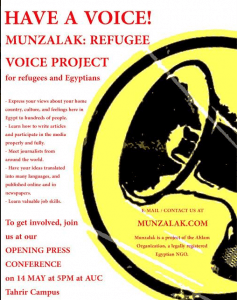

Everyone is here to learn about journalism. Munzalak is a new organization that aims to get refugees living in Egypt involved in the media and in command of their own voice. The name translates to “your comfortable place,” like a home from home – the one you were forced to leave.

Every weekend Munzalak hires out a room at AUC. Refugees are invited to come along and learn the basics of journalism for free. Aurora Ellis, a news editor for an international news agency, runs the workshops with aim of producing “articles that deal with refugee issues and with the refugee experience.”

The ultimate aim is to give refugees a space to voice their experiences. A blog on Munzalak’s website publishes pieces written by refugees (with the option of writing under a pseudonym) while training goes on and – organizers hope – more people join.

Similar initiatives have existed. The Refugee Voice was a newspaper based in Tel Aviv run by African asylum seekers and Israelis inside Israel and founded in April 2011, but is no longer published. Radar, a London-based NGO, also trains local populations in areas around the world (including Sierra Leone, Kenya and India) with the aim of connecting isolated communities.

“We’re being given the opportunity to write about our experiences…I can write about my experiences, and interview other refugees about theirs,” says Edward, a Sudanese refugee who arrived in Cairo earlier this year.

“We have several basic problems – in housing, security, education and health.” He quietly tells stories of life in Egypt; harassment and assault in the streets and pervasive racism (even, he says, from some people who are there to help). “We live a separated life. We are here by force only.”

Ultimately, Edward wants to write a history of the Nuba Mountains, the war-torn area straddling the border between Sudan and South Sudan, where he was born in over 25 years ago. Edward carries a notebook with ideas for this book – scribbled notes of a people and culture disappearing; histories of war and exodus. Edward sees his journalism as self-preservation, telling stories that other people don’t want to be told. He most admires Nuba Reports, a non-profit news source staffed by Sudanese reporters, which aims to break reporting black-spots while humanitarian crises and fighting continues on the ground.

Some activists working alongside refugees see initiatives like this as an important way to break the silence.

“Before June 30, refugees were always neglected in the national media. They were only included [the media] if they were being used as scapegoats,” says Saleh Mohamed from the Refugee Solidarity Movement (RSM) in Cairo. Famous examples include right-wing TV host Tawfik Okasha calling for Egyptians to arrest and attack Syrian and Palestinian refugees on sight. Syrians and Palestinians arrested by security forces have been routinely referred to as “terrorists” by the authorities, a narrative often repeated verbatim by pro-regime newspapers. “Now I think the media wants to keep refugees in the shadows and not talk with them,” Mohamed adds. “You never hear about refugees.”

But Munzalak is not without its risks and challenges. Staying independent but still being able to attract funding and support is one thing. Another is security.

Last Sunday 13 Syrians were sentenced to five years in prison after protesting in March 2012 against Bashar al-Assad. They were charged with illegal assembly and “threatening…security [forces] with danger,” something the defendants all denied, according to state-run newspaper Al-Ahram. A UNHCR official last year had told Syrian refugees to stay away from domestic politics – a warning that could feasibly include journalism as well.

Although historically repressive towards journalists during the rule of Hosni Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s media landscape has taken a significant nosedive since the July coup. Several journalists have been killed in the violence; Mayada Ashraf, a young reporter for Al-Dostour became the latest casualty after she was shot in the head during a protest, allegedly by a police sniper; while reporters remain behind bars and on trial for doing their job.

So is it a good idea to get refugees involved?

Mohamed says that street reporting and visibly working as journalists could put refugees – like Edward – “in danger.” Their legal ability to work also depends on what refugee status they have.

“But otherwise they can talk about themselves rather than waiting for journalists to approach them instead…They definitely need a voice.” But for some refugees, other priorities come first.

Jomana is a 20-year-old Syrian refugee and media studies undergraduate, originally from Aleppo. She visited Munzalak once and liked the idea, but is more concerned about getting a job and paying her way than talking about her experiences – which, like so many Syrian refugees in Egypt nowadays, are harsh. Of almost 184,000 refugees living in Egypt, according to mid-2013 figures from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), around 130,000 of that number are Syrians.

“I don’t have enough money to continue my studies so I will have to leave,” she explains plainly. Jomana’s home was bombed out during the war and they fled the country with just their passports, arriving in Cairo over two years ago. Eventually her father went back to Aleppo to try and restart his old factory, but returned to find rubble. He came back to Cairo to economic uncertainty, incitement and political instability. “Other people are going back to Syria and dying there. Those that stay [here] aren’t dying from bombing or from fighting…but from hunger.”

Munzalak might help, but for some refugees, not in the most crucial of ways.

“It means I can express my opinion freely,” Jomana says, “but will I get paid for my opinion?”

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

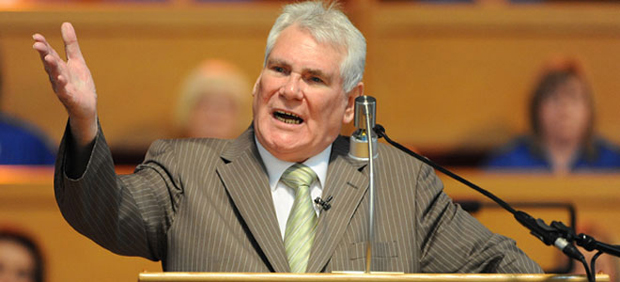

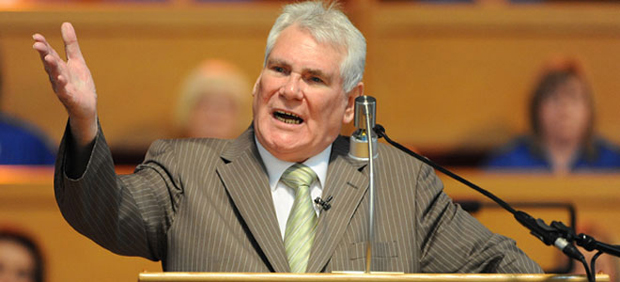

Pastor James McConnell

Belfast’s Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle is one of those things that makes a soft Southern Irish atheist Catholic like me think I’ll never truly understand Northern Ireland.

Every week, Ulster Christians flock from across the province to the 3,000-seater auditorium, there to hear Pastor James McConnell preach his Christian message. Not the Christian message of the BBC’s Thought For The Day, however; you may hear Beatitudes at Whitewell, but it’s not a place for platitudes. This is the real deal, fire and brimstone; damnation and salvation. If you’re not going to Whitewell, you’re going to Hell.

It is a comforting message, and actually, a very modern one. Think of how many politicians these days talk about how they work for hard-working-families-that-play-by-the-rules. Hardline evangelical Christianity is the epitome of that idea. We don’t refer to the “Protestant Work Ethic” for nothing.

But what we tend to forget when discussing hardliners from the outside is that there is a strong apocalyptic element in orthodox monotheistic religion. This is particularly true of Christianity. The closer to the core you get, the more you find Jesus’s teachings are essentially about the end of the world, not some vague being-nice-to-one-another schtick.

For some time, Christians have fretted over Matthew 24, in which Jesus apparently tells of the signs of his second coming, that is, to, say, the end of the world. What worries them particularly is Matthew 24:34: “Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

Does this mean Jesus was telling his apostles that the world would end in their lifetime? CS Lewis, in his work The World’s Last Night, seemed to believe so, and went so far as to call the Messiah’s assertion “embarrassing”. Lewis wrote:

“‘Say what you like,’ we shall be told, ‘the apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the Second Coming in their own lifetime. And, worse still, they had a reason, and one which you will find very embarrassing. Their Master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else.”

“It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.”

Lewis, though himself a Northern Irish Protestant, was clearly not of the same cloth as Pastor McConnnell, Ian Paisley, and the other preachers of their ilk. Orwell disdained Lewis for his efforts to “persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time.” The booming pastors of Northern Ireland, and other Christian strongholds such as the US’s Bible Belt, are very firmly convinced that the end is imminent. And thus, they do not have time to be “jolly nice chaps”. There are souls to be saved, right now.

It’s this attitude that has got Pastor McConnell into trouble in the past week. Recently, at Whitewell, inspired by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, a Sudanese woman reportedly sentenced to death for converting to Christianity, McConnell told the thousands assembled at his temple that “”Islam is heathen, Islam is Satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in Hell.”

In an interview with the BBC’s Stephen Nolan, McConnell refused to back down, claiming that all Muslims had a duty to impose Sharia law on the world, and suggesting they were all merely waiting for a signal to go to Holy War. A subtle examination of modern Islamist and jihadist politics this was not.

The PSNI is now investigating McConnell for hate speech. Northern Ireland’s politcians have been quick to comment. First Minister Peter Robinson backed McConnell, first saying that the preacher did not have an ounce of hate in his body, and then managing to make the situation worse by saying he would not trust Muslims on spiritual issues, but would trust a Muslim to “go down the shops for him”.

Insensitive and patronising that may be, but Robinson also touched on something more relevant to this publication when he said that Christian preachers had a responsibility to speak out on “false doctrines”.

The issue raised is this: if we genuinely believe something to be untrue, no matter how misguided we may be, do we not have a right to challenge it in robust terms? In politics we often bemoan the fact that leaders will not call things as they, or we, see them: indeed, Tony Blair, the bete noire of pretty much every political faction in Britain (a bete noire who oddly managed to win three election) has found grudging praise from across the spectrum this week for suggesting that rather than “listening to” or “understanding” the xenophobic United Kingdom Independence Party, politicians should tackle their arguments head on.

But in religion, we tend to hope that no one will upset anyone too much, in spite of the fact that, for true believers, theological issues are far more important than taxation or anything else.

When Blair’s government proposed (and eventually passed) a law against incitement to religious hatred in Britain, the opposition came from a coalition of secularists and some evangelical Christians, both groups realising, for different reasons, that being able to call an ideology false or untrue – and in the process criticise and question its adherents – was a fundamental right. The trade off in that is acknowledging others’ right to question your truths, something I suspect, judging by the recent controversy in Northern Ireland over a satirical revue based on the Bible, Pastor McConnell and his supporters may not quite excel at.

This article was originally posted on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.