28 Jul 2014 | Awards, News, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda

Playwright David Cecil was nominated for an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Arts Award 2014 after Ugandan authorities deported him from the country for producing a “pro-gay” play in 2013. Determined to continue his work in the Africa, Cecil is now focusing his attention on film production and education in East Africa. With one film school already set up in Uganda, he spoke to Index about his hopes to expand the project to Rwanda and Tanzania, why he believes film in Africa is going to take off in a big way over the coming years and how the situation for LGBT people in Uganda has deteriorated over recent months.

24 Jun 2014 | News, Politics and Society

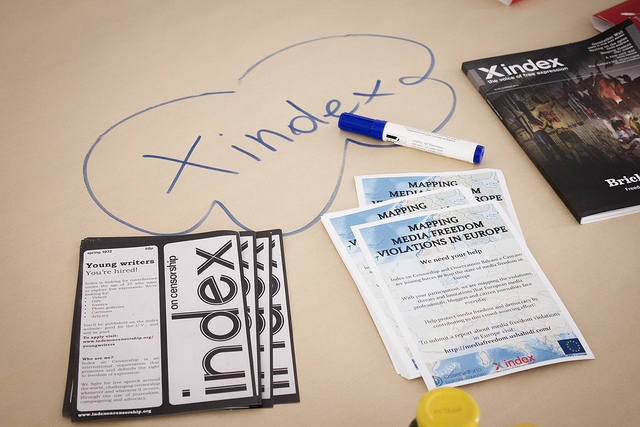

Index speaks at the IAPC meet 2014, Vienna

There has been an 18% rise in violence towards journalists compared to the same period last year, International Media Support, an organisation that works in many of the world’s biggest danger zones, told an international journalism conference.

News from Egypt – as three journalists from Al-Jazeera are sentenced to seven years in prison – demonstrates the huge threats that journalists can face. The subject was covered in detail at this year’s International Association of Press Clubs annual conference in Vienna, which Index on Censorship attended this month.

“Some countries we just can’t work in,” said John Barker from Media Legal Defence Initiative, who help represent journalists facing legal charges for reporting and presented on their work. “Every time we work in Vietnam, for example, the lawyers are arrested. In many places, we can’t transfer money to them.” Nonetheless, they are currently working on 102 cases in 39 countries.

Other topics for discussion included:

- The increasing number of freelancers working in danger zones – and with little training

- How to protect fixers, translators and local journalists

- Possible methods for funding legal representation (Crowdfunding worked as a recent experiment in Ethiopia, said MLDI)

The event was hosted by Austria’s PresseClub Concordia – said to be the oldest press club in the world (founded in 1859 – reformed in 1946, after having its assets seized by Nazis). It was attended by press clubs from around the world, including Poland, Belarus, Syria, the Czech Republic, the US, India, Ukraine, Mongolia, Germany, and Switzerland. Other NGOs – alongside Index, International Media Support and Media Legal Defence Initiative – included the International Press Institute and RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues).

Index was invited to present on the work the organisation is doing around the world, which included sharing the stories of our Freedom of Expression Awards winners and nominees, and news of our current work, including a crowdsourcing project to map media freedom violations across the EU. Plus we also shared stories from our quarterly magazine – including a report on violent threats to journalists in Tanzania and how news stories are getting out of Syria via citizen reports.

Index also hosted round-table discussion on censorship, which provoked an impassioned debate. One of the most interesting topics covered was on contracts that some journalists are being made to sign on what they can and can’t write. We heard of cases in Mongolia and Germany. We also discussed self-censorship and censorship by complying to advertisers’ will. One attendee from the Berlin Press Club said: “There is no censorship in Germany, but journalists feel like they have scissors in their heads. You have to self-censor before you write.” This is an area that we are researching, so please get in touch if you have experiences and examples.

The meeting also visited a new exhibition on censorship during WW1 and ended with the Concordia Press Club’s annual ball, which is a key fundraiser for the club and attended by over 2,000 guests. See photos from the event below.

This article was posted on June 24, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Jun 2014 | Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we include a special report: Brick by brick, freedom 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

As Europe prepares for the anniversary of the wall’s demolition in November, Index on Censorship looks at how the continent has changed. Author Irena Maryniak explores the idea of a new divide that has formed further east. Polish journalist Konstanty Gebert looks at how Poland’s media came out from the underground and lost its voice.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”58030″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Award-winning German writer Regula Venske shows how Germany has tackled its identity issues through crime fiction; and Helen Womack reports from Moscow on the fears of a new Cold War. We also give voice to “Generation Wall” – the young people who have grown up in a free eastern Europe.

When the wall came down in 1989, there were discussions in the Index office about whether our battles were over. Sadly, we all know there was no universal end to censorship on that day. This issue also shares stories of the continuing fight for free expression worldwide, from a scheme to fund investigative journalism in Tanzania to an ambitious crowdsourcing project in Syria.

Also in this issue:

• Dame Janet Suzman looks at censorship of South African theatre on the 20th anniversary of South African democracy

• Jim Al-Khalili shares his thoughts on threats to science research and debate

• Ex BBC World Service boss Richard Sambrook goes head-to-head with Bruno Torturra, from Brazil’s Mídia Ninja, to debate the future of big media

Plus:

• Two new short stories – exclusive to Index – from Costa first novel winner Christie Watson and Turkish novelist Kaya Genç

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: BRICK BY BRICK” css=”.vc_custom_1483610192923{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Freedom 25 years after the fall

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Oct 2013 | Africa, News, Politics and Society

In June 2013, police and protesters clashed at the offices of the Daily Monitor, Kampala. Picture Isaac Kasamani/Demotix

In the age of technology with high-speed Internet access and smart phones, it is sometimes easy to imagine that all journalists’ working lives are the same: deadlines, insufficient resources, worrying about the threats of digital media and the race to break news.

In some ways these concerns are indeed universal. However, what journalists in North America and Europe hardly ever have to worry about is their basic right to report the news. It is true that in a post-Wikileaks and News of the World journalistic environment, all reporters have had to consider their fundamental role in providing news and information and analysis ethically. However, in Africa many journalists find themselves carefully tiptoeing through minefields of media laws which limit their ability to report accurately and truthfully on the news of the day, particularly when reporting on activities of the powerful in government.

Recently in Swaziland, a journalist has been charged with contempt of court for reporting the fundamental issue of whether or not the Chief Justice is fit to hold office, given that he is the subject of impeachment proceedings back in his own country, Lesotho. Several Zambian journalists were brought to court earlier this year, initially accused of sedition. In Ethiopia, journalists are serving time in prison, sentenced for threatening the state with their reports.

Besides individual actions taken against journalists, whole media enterprises are also at risk. In Tanzania, the two newspapers Mwananchi and Mtanzania have been suspended by the unilateral action of the Minister of Information citing breach of the peace concerns – Mwananchi was reporting on new salary structures in the government. Earlier this year, the newsroom of the Ugandan newspaper Daily Monitor was under siege for over a week, while police was trying to find letters that were exchanged between editors and a source.

There is no doubt that much state action against journalists and media houses is unconstitutional. However, there is also no doubt that Africa’s media laws do make provision for draconian action to be taken against journalists and publications.

The Konrad Adenauer Stiftung’s Media Programme has recently published a two-volume Media Law Handbook for Southern Africa, written by Justine Limpitlaw. The handbook is available for free download on the internet. One of the most important aims of the handbook is simply to provide information about what the law is in a number of southern African countries. Statutes are often not available electronically and many journalists simply have no idea about what the laws governing the media are.

A key characteristic of many southern African countries is a media law landscape with a relatively benign liberal constitution at the apex. All constitutions protect freedom of expression to some extent. However, very few changes have been made to media legislation to ensure that the legislation accords with the constitutional right to freedom of expression. Despite oft-expressed anger at the colonial era and its on-going repercussions for the continent, African political elites have essentially retained colonial era media laws as is.

One only has to list many in-force statutes to note that African media law appears to have stultified in the early or mid-20th century. Both Lesotho’s and Swaziland’s Sedition legislation dates back to 1938. Swaziland’s Cinematograph Act is from 1920. Many countries’ Penal Codes date back to the 1960s – prior to their independence from Colonial powers. These Penal Codes criminalise many forms of expression including defamation, insult and false news, and provide for significant jail sentences.

Sadly few attempts have been made to update African media laws. On the rare occasion where a country has engaged in media law reform, the results have been decidedly mixed. South Africa’s attempt to update apartheid-era security laws has been roundly condemned for promoting governmental secrecy at the expense of the public interest.

There is hope. In 2010, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights adopted Resolution 169 on Repealing Criminal Defamation Laws in Africa. The resolution calls on states parties to repeal criminal defamation and insult laws which impede freedom of speech. In May 2013, the Pan African Parliament adopted the Midrand Declaration on Press Freedom in Africa. The Pan African Parliament resolved to launch a campaign entitled “Press Freedom for Development and Governance: Need for Reform” in all five regions of Africa. These initiatives by intergovernmental African organisations are historic and represent a real opportunity for media law reform. There is also significant pressure being brought to bear on a number of countries to enact access to information laws.

The objective link between a free press and accelerated development is clear. Sadly governments appear all too willing to forego development in their desire to retain political control. Journalists are under real threat in many countries in Africa and the threats are not only from rogue police officers but also from ordinary police officers and other state functionaries merely carrying out the letter of the law.

The Konrad Adenauer Stiftung believes that the media Law handbook could act as a catalyst for bringing together journalists, media owners, members of the judiciary, government officials and media activists to have a serious look at African media law with a view to taking it out of the colonial era. Together with the Pan African Parliament’s and the Comission’s efforts, this is a great opportunity to make Africa a place where journalists can report the news of the day accurately and fairly without fear of arrest and imprisonment.

This article was originally posted on 22 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org