16 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

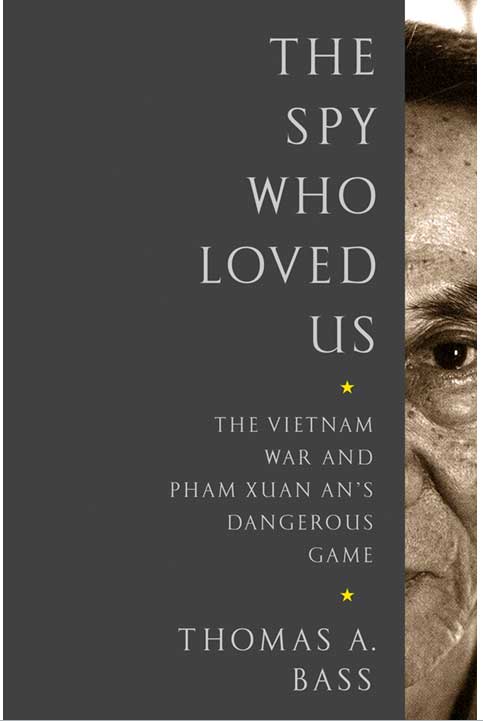

I meet Bao Ninh again in 2014, when I am visiting Hanoi after the publication of The Spy Who Loved Us. I arrive at his house at seven in the evening, again with a translator and an assistant who wish to remain anonymous. Also with me are my twin sons, who will be celebrating their twenty-first birthdays in Hanoi. The evening heat is wrapped around us like a clay pot baking in Hanoi’s summer oven, Ninh uncorks a bottle of Chilean red wine and welcomes us into a living room that looks cheerier than the last time I was here, with the neon tubes on the wall not quite so pallid and a new sofa angled next to his chair, which is placed looking out toward the front door.

Ninh’s wife, Thanh, has skipped her exercise class to come home and cook dinner for us. A secondary school teacher with a wary smile, she has fried up a few dozen egg rolls, which are laid out on the coffee table along with bowls of hot sauce and nuoc mam fish sauce. I have brought soft drinks, pastries, and beer. Ninh urges us to begin eating, and my sons tuck into the meal. Our host sticks to drinking wine while Thanh flutters in and out of the kitchen. We chat about Ninh’s son, who now works in Saigon for Vina Capital, an investment company.

“It’s a different world from the one I know,” he says. He himself has retired from writing for Bao Van Nghe Tre, the literary journal for which he used to pen a weekly column. Now he works for himself, rising at midnight to write through the night, and then shredding his work at dawn, or so he says. Even relaxed over a glass of wine, Ninh is reticent about discussing his work.

When I broach the subject of his two unpublished novels, Ninh tells me that I have the wrong titles for his books and that he never wrote one of them anyway, except for a short piece that was published somewhere (he can’t remember where). Ninh has a way of shaking his head from side to side and grinning under his moustache when he disagrees with you or wants to avoid talking about something. So forget about discussing censorship, internal exile, or other sensitive subjects. He is not going to retell his story about how a thousand South Vietnamese POWs were brought North to impregnate a thousand widows in Ho Chi Minh’s natal village—even if this tale summarizes in one allegorical masterstroke the history of postwar Vietnam.

Ninh complains about the heat, and then he starts complaining about the Chinese, which is currently the number one topic in Vietnam. On April 30th—Vietnam’s national holiday for marking the unification of north and south Vietnam, the day you pick if you want to kick your enemy in the nuts and then spit in his eye—China moved a billion-dollar oil rig into Vietnam’s offshore waters and started drilling for oil. China surrounded the rig with an armada of ships and chased off any Vietnamese boats that dared to approach. The Chinese rammed Vietnamese coast guard vessels. They sank fishing boats. They fired water cannons that looked like medieval dragons spouting blue flames. As silly as these dragon boats may have looked, they proved quite effective at destroying electrical gear on the Vietnamese boats that were forced to flee.

Following this Chinese aggression, thirty thousand Vietnamese rose up in protest and started sacking Chinese textile factories around Saigon. Mobs burned at least fifteen companies and damaged another five hundred before police got the area locked down. Speculation abounds about the cause of these riots. They were orchestrated by government agents or by anti-government agents or by criminal gangs or by the Chinese themselves, since the looted factories turned out to be owned by Taiwanese and Koreans.

“We are experts on China,” says Ninh. “We just don’t talk about it. They are always smiling, but their smile is dangerous. They will be the nightmare of the world. By 2030, China will be far stronger than the United States. Our civilization will be threatened. I’m pessimistic. I see no light at the end of the tunnel,” he says, using a phrase employed by Richard Nixon during the Vietnam war. “I see only darkness,” Ninh says. “The younger generation should prepare. I feel a black cloud coming. Danger is approaching.”

Now that the red wine is gone, Ninh fills his glass with white and urges us to eat more egg rolls. Our host has a thatch of salt and pepper hair, now more salt than pepper, and a Fu Manchu moustache that gives his face the look of a window shuttered behind Venetian blinds. Wearing dark slacks and a white, short-sleeved shirt, he has kicked off his sandals and is cooling his feet on the linoleum as he settles back in his chair to ponder the dark cloud floating over Vietnam. It is quiet out on the street, save for the occasional motorbike rolling down the lane, but Ninh tells us how, during the day, he hears a constant din from the loudspeaker attached to a pole outside his door. The Party directives and propaganda become increasingly strident around holidays, the worst being April 30th, which commemorates the day in 1975 that Bao Ninh and his fellow soldiers captured Saigon.

“They talk about the old victories over and over again,” he says. “Even as a soldier I don’t like it. It’s like telling a beautiful girl she’s beautiful. She already knows she’s beautiful; so all you’re doing is annoying her. Next year, which marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the war, it’s going to be really annoying,” he says.

I have given Ninh a copy of my newly-published book. He keeps fingering it, flipping through the pages, stopping now and then to study a passage. “I don’t like intelligence agents and the police,” he says. “Maybe I’ll like them better after I read this.”

Ninh pours himself another glass of wine. “I never met Pham Xuan An,” he says. “He was a big general. I was just a soldier. Now that the government has made him a hero, they’ve started telling young people to act like him, which is really stupid. It’s like telling American teenagers they should grow up to be like Lyndon Johnson.”

Ninh stops to read the opening paragraph. “This is how you can tell if a translation is worth reading,” he says. “It looks pretty good.” Later he will send me an email praising the book and telling me how much he enjoyed reading it, even with the missing passages.

Ninh’s face is animated by the thick eyebrows that sweep over his black eyes. He windmills his hands through the air and slaps the back of his head. Then he pushes his hands in front of him like a surf swimmer heading for deep water. “The more we understand the Chinese the more we fear them,” he says. “Hitler was able to come to power because he was helped by Britain and France. They took care of him. The same is true with the United States and China. The Americans built up China’s industrial capacity. You moved your factories to China. You made the Chinese strong by doing business with them, but this strategy is going to fail in the end, just like it failed with Hitler.”

I nudge the conversation back to writing. “We have to follow the Communist Party line,” he says about censorship in Vietnam. “Every writer knows this. You’re hired for a reason; so don’t talk back. If you don’t accept the censorship system, then don’t be a writer.”

“They want to make Pham Xuan An into a political commissar,” he says. “This is why they censored your book. A good intelligence agent is like a priest. He keeps his secrets to himself.” The secrets of Pham Xuan An could be revealed only after the war and only selectively, after having been shaped into a heroic tale.

“For Vietnamese readers, a book without any cuts is a surprise,” says Ninh. “People will know where your book was cut. I prefer to read the printed version, but young people will go online to learn what you really wrote. This is becoming second nature for us, and soon we won’t have any printed books at all.”

He tells me he is writing a new novel, but he won’t say what it’s about. “We have to work quietly and not talk about it to anyone,” he says. “My time is over. I just write. I don’t publish.”

I ask him what Vietnamese writers I should be reading. “There is no generation of young writers,” he says. “There are just some individuals, one or two that I read.”

Next we talk about the movie that was being made of his novel. Film rights to The Sorrow of War were sold to a young American producer, Nicholas Simon, who also wrote the screenplay, but the project unraveled a few days before filming was to start. “We didn’t understand each other,” says Ninh. “We’re both stubborn people. He was young. He knew nothing about Vietnam. The script was so far from reality that it was ludicrous. I kept editing it, but it never got better. I yelled at him in Vietnamese. He yelled at me in English. The translator cried. Finally, the main investor, who was a friend of mine, fled after seeing our inability to get along. A movie has to be easy. My book is too hard to make into a movie.”

Before saying goodnight, Bao Ninh offers his final word on the subject of censorship. “Some guy who grew up as a peasant has the right to mess with your work? No one has the right to censor a book. When politics enters the room, ethics flies out the door. Other countries have laws protecting writers. In Vietnam, we have nothing. There are no rules to follow. The politicians make the rules.”

Part 12: The struggle

This eleventh installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 16, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

It is a steamy night in June when I meet Bao Ninh at his house in Hanoi, where we will spend the evening chatting and sweating over green tea. Located in an old part of the city, the house has the usual barred gate opening into a covered patio filled with motorbikes. Behind the bikes lies a narrow room with yellowed walls lit by neon tubes. The room is furnished with a black couch, a couple of chairs, and a coffee table holding lychees, biscuits, and our bitter tea. I am accompanied to this meeting by my Vietnamese assistant and another young woman who is serving as our translator.

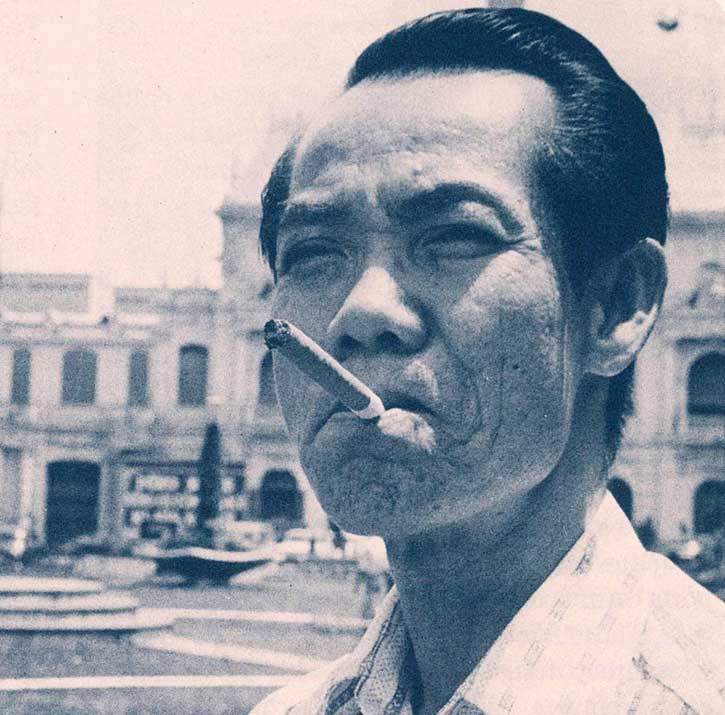

Ninh strikes me as hyper-cautious, with the kind of wariness one develops after many years spent trying to avoid people who want to kill you. Curled in a chair, ready to spring, his body looks as if it has muscles that have forgotten how to relax. When it enters my mind I can’t shake the idea that he has eyes in the back of his head. It is a large head, crowned with silver hair. Ninh’s eyebrows sweep over glancing black eyes, above sunken cheeks and a drooping mustache. Wearing a brown, short-sleeved shirt and black trousers, he chain smokes Camel Lights through smoke-stained fingers. A fan blows on us as we sit in the yellow gloom.

The next thing I notice about Ninh are his feet. He is barefoot, with wide, spatulate toes gripping the linoleum. Sunburned and flat, these are the feet of someone who spent years walking in rubber sandals, made out of old truck tires, down jungle paths with a backpack on his shoulders and an AK 47 in his hand. These are the feet of a peasant warrior whose physical needs have been stripped to a bare minimum. As he stares at me through his narrowed eyes, I realize that I am traveling heavy, with notebooks, digital recorders, and two assistants, while Ninh is still traveling light.

This first visit falls on National Journalists’ Day, which is celebrated mainly through bottoms-up drinking with one’s fellow cadre. Ever since his career as an author got derailed, after the denunciation campaign that began in the early 1990s, Ninh has supported himself writing a column for Literature newspaper (Bao Van Nghe), published by the Vietnamese Writers Union. “In principle, I have to go to work every day, but I am an old man, so I stay at home instead of going to the office,” says the author, who at the time was fifty-six. “I write an article a week. My last piece was on the countryside, about illiteracy among rural kids who are so poor that they have never been taught to read.”

After years of penning his inoffensive columns for Literature, Ninh was allowed to publish a short story collection in 2002 and another collection in 2005 called Daydreaming During a Traffic Jam. “As is usual in Vietnam, the publisher printed two or three thousand copies of Daydreaming and then allowed the book to go out of print,” he says. “You will have a hard time finding it now. I don’t even have a copy.” One story in the volume was translated and published in English as “Savage Winds.” “The title refers to the wind that blows in the Central Highlands,” he says. The rest of the stories remain untranslated. When I ask him if he minds his literary obscurity, Ninh shrugs. “I only care about the royalties,” he says.

In 2006, Ninh was also allowed to release a Vietnamese version of The Sorrow of War, for which he was paid a few thousand dollars. “The book has been translated and published in ten countries,” he says. “I don’t know anything about these translations. People tell me that sometimes parts of the text have been left out.” Again, he tells me how much he appreciates the royalties from these foreign publications.

“I have written two unpublished novels,” he says, when I broach the subject of censorship. “I do not intend to publish them.” The first, called “A Plain of Grass” (“Thao Nguyen”), is about a platoon of soldiers who capture a Montagnard village in the Vietnamese Highlands. Here they find a white missionary who has filed down his teeth like a Montagnard and gone native. What do the soldiers do with their half-white, half-Montagnard captive—kill him, set him free, or ship him to Hanoi? The question divides the unit, and they begin fighting among themselves. “The central character is a Catholic priest,” says Ninh. “The story is set during the war, when times were very different than they are now. We were ardent communists back then.”

“The second novel is about the interrelation of cultures and people, about the mixing of cultures. It, too, is about the war,” he says. The final, yet-to-be-named volume in Ninh’s trilogy is the most incendiary. It tells the story of South Vietnamese prisoners of war who have been sent to a POW camp in the north. (I have been told that the camp is located in Ho Chi Minh’s natal province of Nghe An.) Since most of the village men have died in the war, the local women mate with the southern soldiers and produce a new Vietnamese race, blended from Ho Chi Minh northerners and defeated southerners.

“The novel deals with soldiers, President Thieu’s soldiers,” says Ninh, referring to soldiers in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. “After the war they are arrested and sent to the north, to undergo a kind of brainwashing. Ten years later they are released.”

“My son has a girlfriend, who is the daughter of a Republican soldier,” he says, confirming that the new, blended Vietnam is already here. His son at the time is working in Hanoi for an American investment firm. “It is safe to have money now,” says Ninh. He mentions that his son appeared recently on TV, in a program about Vietnamese youth, and how he is helping to organize a film festival in Hanoi. “It’s strange to me how Vietnamese youth like American movies,” he says. “Americans and Vietnamese have something in common. We Vietnamese are often mistaken for Chinese, but we are very different. We are more open than the Chinese, more like Americans.”

Ninh returns to narrating the plot of his novel. “The soldiers are brought to the north.”

“To Nghe An province?” I ask.

Bao Ninh at his house in Hanoi (Photo: Thomas Bass)

|

“I didn’t say that,” Ninh says, narrowing his eyes and retreating behind a cloud of cigarette smoke. Everyone knows that if he mentions Nghe An province, the book will be read as a commentary on Ho Chi Minh. He wants to drop the subject. “It is too difficult to understand,” he says. I urge him to continue.

“They are sent to a labor camp, in a residential area. Some northern women get pregnant. The soldiers are released and go to America. Then they return from America, to visit the women and their children.”

“So at this point the soldiers are viet kieu,” I suggest, using the term for exiled Vietnamese.

“You are right, but the Vietnamese people don’t like the term viet kieu,” he says. “This originated from the Chinese, and now you Americans use the term, but we prefer to say nguoi viet hai ngoai, overseas Vietnamese, which is more precise.”

“Do the soldiers stay in Vietnam?”

“Are they happy?” Bao Ninh replies. “It depends. Life in America is easier. They keep their American nationality. This is a fable about the history of Vietnam. It was written a couple of years ago. I do not intend to publish this now. For me, writing is more important than publishing. This is a story from the past.”

“Usually I never talk about my books, only with my closest friends,” he says. “I wrote the novel from my personal interests. I wrote about Vietnamese soldiers who worked with Americans. I tried to find out special things about Republican soldiers. I tried to understand them.”

“Did you succeed?”

“No one can understand another person fully,” he says. “I believe I understood them. It took me a long time, actually from the end of the war until now. I have traveled to the south a lot. I stayed in the south for several months after the end of the war. Many of my relatives live in the south. My younger sister, a teacher, lives there. It’s easier to earn money in Saigon than in Hanoi.”

As if to skirt away from a sensitive subject, Ninh says, “I haven’t finished writing the book yet. I spend most of my time drinking with friends.”

“Drinking what?” I ask.

He leans over and writes in my notebook “bia hoi,” draft beer, and then jokingly gestures toward my colleagues, “This is not a suitable subject for your translator,” he says.

“Middle-aged people like me are undisciplined,” he says. “I write at night, for three to four hours, starting after 10:00 p.m. I was born in the Year of the Cat, and cats don’t sleep at night. Writing is not an occupation here in Vietnam. It is a hobby. You don’t earn any money for it.”

My final question concerns Duong Thu Huong, one of whose books, Novel Without a Name, contains a number of passages resembling his own work. Ninh avoids the question. “There’s a lot of false information about her, saying she isn’t respectable, which isn’t true,” he says. “I have read all of her books, even those not allowed to be published in Vietnam because she is anti-communist.” To get my question answered, he suggests I go to Paris and ask Duong Thu Huong herself.

Part 11: The black cloud

This tenth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 13, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

With the censor’s boot on their necks, a generation of Vietnamese writers has been forced into silence or exile. To report on their plight, I met with three of the country’s best-known authors: Bao Ninh in Hanoi, Duong Thu Huong in Paris, and Pham Thi Hoai in Berlin. Each had his or her own story to tell about censorship, arrest, banishment, or silence—realities that are becoming increasingly dire in Vietnam.

Bao Ninh (whose real name is Hoang Au Phuong, with Bao Ninh being the name of his family’s native village) was a seventeen-year-old student when he enlisted in 1969 as an infantryman in the 5th Battalion/24th Regiment/10th Division. He would spend six years fighting his way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, surviving some of the war’s deadliest battles, before his regiment captured Saigon’s Ton Son Nhut airport in 1975. Of the five hundred men who joined his military unit in 1969, Ninh is commonly reported to be one of ten who survived.

Son of Hoang Tue, former director of Vietnam’s Linguistics Institute, Bao Ninh went back to school after the war and finished college in 1981. He worked briefly in a biology lab at Vietnam’s Science Institute and then picked up his pen to become a writer. In 1984, the thirty-two-year-old former soldier enrolled in the second class admitted to the Nguyen Du Writers School (named after the celebrated Vietnamese poet who wrote The Tale of Kieu). For his school thesis, Ninh wrote a novel about his war-time experience. “The Sorrow of War” began circulating around Hanoi in roneo form in the late 1980s. This stenciled duplication, similar to a mimeograph, was published in 1990 under the anodyne title Fate of Love. The original title was restored in a 1991 edition and then removed again when Fate of Love was reissued in 1992. The book won a major literary award and became instantly famous—too famous, apparently. A denunciation campaign was launched against Bao Ninh, his literary award was retracted, and his book went out of print. In fact, it went out of print for a decade. “The time is not right” to republish it, he was told. Fate of Love reappeared in 2003, but it was not until 2006—fifteen years after its original publication—that The Sorrow of War reappeared in Vietnam. The Vietnamese use a variety of euphemisms to describe this gap in Bao Ninh’s literary career, but the correct term is censorship. He was not thrown in prison or banned. In fact, he was rewarded for his silence, but he was censored, nonetheless.

Translated into English by Vietnamese poet Phan Thanh Hao and Australian journalist Frank Palmos, The Sorrow of War sparked another literary sensation when it was published in London in 1993. The book revealed that Vietnam’s veterans on the winning side suffered the same trauma and disillusionment as the losers. Hailed as a great novel, comparable to Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, The Sorrow of War has been republished in a dozen languages and named by the Society of Authors as one of the fifty best translations of the twentieth century.

While the novel was becoming a best-seller in the West, in Vietnam the book reverted to being passed hand-to-hand in pirated editions. Bao Ninh stopped writing, or, to be more precise, he stopped publishing. He took a government job, and his son was allowed to leave the country to study economics at the University of Massachusetts. The Sorrow of War is currently widely available in Vietnam, but its two successor volumes remain unpublished.

At my first meeting with Bao Ninh in Hanoi in 2008, we talked about his unpublished books. He assured me the works had been written, gave me their titles, and described their plots. I have to say that I have not personally verified the existence of these manuscripts, which have assumed a status in Vietnamese literature comparable to Captain Ahab’s great white whale—doubted by many, believed by some, seen by few. The subversive nature of Bao Ninh’s trilogy is revealed only after confronting the shock of the first volume. The Sorrow of War may be a great war novel, but it holds a double surprise for readers in the West by revealing the bitterness of NVA soldiers, the soldiers who won the war. They were betrayed by incompetent commanders and self-serving politicians. They were scorned by a post-war generation that wanted to forget the incredible suffering inflicted on Vietnam during thirty years of war and turn instead to making money. The survivors of the war are ravaged by guilt, attacked by bad dreams. They drink too much, brawl too much, and drift all too often from failure to suicide. They display all the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, shell-shock, battle fatigue, or whatever we call the soul-sucking misery that invades a soldier’s bones at the sight of men killing other men.

The “friendly, simple peasant fighters … were the ones ready to bear the catastrophic consequences of this war, yet they never had a say in deciding the course of the war,” writes Kien, the narrator of the novel, who, like its author, spent a decade fighting Americans in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. “We have so many of those damned idiots up there in the North enjoying the profits of war, but it’s the sons of peasants who have to leave home,” he writes in a manuscript that turns out to be the book we are holding in our hands.

At war’s end, the former infantryman is detailed into recovering the corpses of his fallen comrades. “Over a long period, over many, many graves, the souls of the beloved dead silently and gloomily dragged the sorrow of war into his life.” He returns to his native Hanoi in 1976 to find the city consumed by careerism, graft, corruption, and all the other ailments of an emerging Asian Tiger. The political propaganda is ham-fisted. His former fiancée is a prostitute. He joins the ranks of the “traumatized misfits” who survived the war, works as a journalist, and writes a novel that sits abandoned on his desk, until the pages blow away in the wind.

“Those who survived continue to live,” writes Kien. “But that will has gone, that burning will which was once Vietnam’s salvation. Where is the reward of enlightenment due to us for attaining our sacred war goals? Our history-making efforts for the great generations have been to no avail. What’s so different here and now from the vulgar and cruel life we all experienced during the war?”

“In this kind of peace it seems people have unmasked themselves and revealed their true, horrible selves,” Kien says to a fellow veteran. “So much blood, so many lives were sacrificed—for what?”

“I’m simply a soldier like you who’ll now have to live with broken dreams and with pain,” his colleague replies. “But, my friend, our era is finished. After this hard-won victory fighters like you, Kien, will never be normal again.”

Kien is wracked by the kind of survivor guilt that comes from knowing “that the kindest, most worthy people have all fallen away, or even been tortured, humiliated before being killed, or buried and wiped away by the machinery of war.” He is left with the “appalling paradox” that “Justice may have been won, but cruelty, death, and inhuman violence have also won.”

On the two occasions when Bao Ninh was allowed to travel to the United States (he visited Boston in 1999 and Texas in 2005) he gravitated to the war veterans in the crowd. They swapped reticent greetings, established whether they had carried guns or flown airplanes, and then started drinking, letting the silence fill with the ghosts of departed friends. Bao Ninh had more dead friends than the Americans, and they died more gruesome deaths, but dead is dead, and he bore no grudges as he sat among his fellow soldiers. “Soldiers never say ‘sorry’ to each other,” he told me later. “They have nothing to apologize for.”

When former U.S. marine Wayne Karlin met Bao Ninh at a hotel café in Hanoi in 2007, Karlin was reminded of another Vietnam veteran turned writer, Tim O’Brien. “Both men are compact, their faces not so much sharp as sharpened, their eyes bright, at times with a flare of pain, at times with a gleefully malevolent intelligence, a sardonic, challenging grunt’s stare. And they both smoke like hell,” wrote Karlin in his book Wandering Souls (2009).

I am not a former soldier who fought in Vietnam, but the war was the cloud under which I came of age, and I seized the chance to begin traveling to Vietnam when the country opened to outsiders in the early 1990s. I met Pham Xuan An on my first trip in 1991, when the journalist-spy was still under police surveillance, and I kept returning to see him as I wrote my New Yorker profile and then my book, both entitled The Spy Who Loved Us. After An’s death in 2006, I visited Vietnam again two years later to talk to sources reticent about speaking while he was alive, and it was on this trip that I first met Bao Ninh.

Part 10: Eyes in the back of his head

This ninth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 11, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Nguyen The Vinh, editor at Hong Duc publishers, is the last censor I meet on my Vietnamese publishing tour. I am to appear at a Hanoi book fair for an author signing and then sit on a panel discussing my book. Flanking me are the sober Vinh, who, like many editors, seems to prefer books to authors, and another gentleman, Duong Trung Quoc, who also had a hand in getting my book published. Quoc is an historian and politician. I don’t know what kind of history he writes, but, as an elected member of Vietnam’s National Assembly, Quoc—a hearty fellow who resembles a Vietnamese Bill Clinton—is obviously a successful politician.

I try to hide my annoyance when most of the evening is devoted to discussing Pham Xuan An as a “perfect spy.” Remember, Vinh has edited—and censored—both the “official” biography of An and my own work. I have been advised to curb my tongue and not jeopardize the continued sale of my book. The ordeal continues over dinner, where I am still holding my tongue, while Vinh and Quoc tuck into a multi-course feast. In spite of their work doing the final pruning of my book, these men are the rainmakers who got it published. I owe them a couple of bucks in royalties, which I think I’ll donate to some of the millions of needy souls in Vietnam’s post-war diaspora. By the time our meal has moved from sautéed vegetables to steamed fish, my tongue has slipped enough to broach the subject of censorship.

“By law there is no censorship system in Vietnam,” says Vinh. “Mainly what we have is self-censorship.”

Quoc the politician agrees with his literary friend. “Here in Vietnam censorship is inside the brain of everyone,” he says. “It was your editors who cut your book, not the government.”

I ask them to elaborate on how a country without censorship manages to censor so many writers. “Publishers belong to the state,” says Vinh. “Everyone who works in the system understands this. For the higher purpose of the nation they have to sacrifice something. We have an expression here in Vietnam: ‘It is better to kill an innocent man than let a guilty one escape.’”

Quoc allows a smile to spread across his face, before gently chiding his friend. “You are speaking like a political commissar,” he says.

Later in the evening Quoc will hint at why my book was finally published after having been blocked for five years. “The authorized biographies on Pham Xuan An were works of stenography,” he says. “People printed what he told them to print. Your book is something different. It is documented and researched, but, more importantly, it captures his personality. This is why I thought it should be published.”

I take the compliment, but note that my book has not actually been published in Vietnam. A promotional teaser is for sale, while a complete Vietnamese translation can exist only outside the country. This will happen when the book is retranslated and released in Berlin as an electronic file stored on computers hardened against attacks from Vietnam’s censors. That Vietnam has censors trying to reach across the world and disable computers in Berlin makes these agents far less benign than Vinh would have me believe. In this case, the censors are working not as freelance gardeners, shaping topiaries in their minds, but as political operatives executing orders to attack people in foreign countries.

As we move from fish to grilled meats, Quoc indicates that he is going to give me an important scoop. Not only did Pham Xuan An continue working as a spy after the end of the Vietnam war, but he did so at the highest levels. “He was hieu truong, or dean, of the post-war military intelligence school in Ho Chi Minh City.” An’s eight-month stint in 1978 at the Nguyen Ai Quoc National Political Academy in Hanoi had prepared him for this important assignment.

I have seen no evidence supporting this claim, and, in fact, I suspect it is part of the propaganda campaign designed to make Pham Xuan An into a perfect apparatchik. The claim is even more improbable, because, earlier in the evening, Quoc had confessed that An, as a southerner who had worked for the Americans, was always distrusted by his northern colleagues. “People in Pham Xuan An’s position were not trusted by the government,” he says. “There were a lot of questions about him.” Apparently, these questions will remain unanswered for a long time. “It takes at least seventy years for documents in Vietnam to be declassified,” he says.

Later, to verify Quoc’s claim that Pham Xuan An was dean of Vietnam’s spy academy, I visit Bui Tin in his one-room garret in Paris. Tin is another famous journalist spy. He was deputy editor of Nhan Dan, Vietnam’s Communist Party newspaper, when he penned an editorial in the spring of 1990 praising the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the introduction of democratic reforms into the communist world. He was about to be cashiered by the Politburo, which was preparing to sign a secret agreement allying Vietnam and China. (“The Thanh Do agreement in September 1990 was the beginning of the Chinese colonization of Vietnam,” he says.) To avoid being arrested, Tin left his wife and two children in Hanoi and flew to Paris for a meeting of communist newspaper editors. After the meeting, he didn’t fly home. He thought the situation would reverse itself in a year or two. Vietnam’s progressive forces would regain the upper hand and reintroduce democratic reforms into the country. Twenty-five years later, Tin is still in Paris, while his wife, whom he has not seen since 1990, remains “under close surveillance” in Hanoi.

As an army colonel and confidante of General Giap, and as a fellow journalist who befriended Pham Xuan An after the two men met in 1975, Tin is a reliable source for double checking Quoc’s information. “Yes, Pham Xuan An wrote reports on his visitors,” Tin confirms, “and every once in a while he was asked to give lectures to the Ministry of Interior spies being trained in Saigon. But he was nothing as grand as the dean of a spy academy. The government treated him like an interesting artifact. He was a bauble they toyed with and admired. He was good for propaganda, but they never trusted him.”

In spite of his dubious pronouncements, I have warmed to Quoc as we plowed through a steady round of beers and ended the evening with toothpicks propped in our mouths, a sign of having eaten well. Quoc had surprised me with another confession. Unlike the old days, he said, the Vietnamese government is not run by intellectual giants and military geniuses. “Today the government of Vietnam isn’t smart enough to allow a Pham Xuan An to do what he did,” he says. “It requires bravery and intelligence to run a spy like that. What is your expression in English? ‘The first victim of war is truth.’ Here in Vietnam, we have the habits of war.”

By this point in the evening, convivial friends at the end of a good meal, agreeing on almost everything, my censors and I have begun toasting each other, bottoms up.

Part 9: Wandering souls

This eighth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 11, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org