By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

“For Vietnamese readers, a book without any cuts is a surprise. People will know where your book was cut” |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

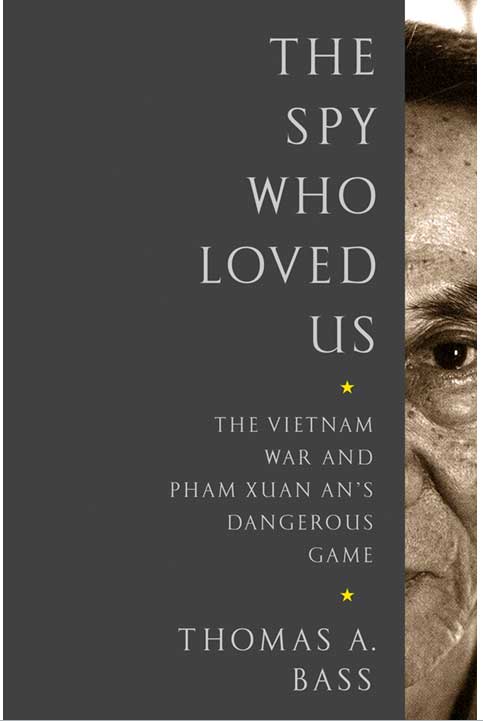

I meet Bao Ninh again in 2014, when I am visiting Hanoi after the publication of The Spy Who Loved Us. I arrive at his house at seven in the evening, again with a translator and an assistant who wish to remain anonymous. Also with me are my twin sons, who will be celebrating their twenty-first birthdays in Hanoi. The evening heat is wrapped around us like a clay pot baking in Hanoi’s summer oven, Ninh uncorks a bottle of Chilean red wine and welcomes us into a living room that looks cheerier than the last time I was here, with the neon tubes on the wall not quite so pallid and a new sofa angled next to his chair, which is placed looking out toward the front door.

Ninh’s wife, Thanh, has skipped her exercise class to come home and cook dinner for us. A secondary school teacher with a wary smile, she has fried up a few dozen egg rolls, which are laid out on the coffee table along with bowls of hot sauce and nuoc mam fish sauce. I have brought soft drinks, pastries, and beer. Ninh urges us to begin eating, and my sons tuck into the meal. Our host sticks to drinking wine while Thanh flutters in and out of the kitchen. We chat about Ninh’s son, who now works in Saigon for Vina Capital, an investment company.

“It’s a different world from the one I know,” he says. He himself has retired from writing for Bao Van Nghe Tre, the literary journal for which he used to pen a weekly column. Now he works for himself, rising at midnight to write through the night, and then shredding his work at dawn, or so he says. Even relaxed over a glass of wine, Ninh is reticent about discussing his work.

When I broach the subject of his two unpublished novels, Ninh tells me that I have the wrong titles for his books and that he never wrote one of them anyway, except for a short piece that was published somewhere (he can’t remember where). Ninh has a way of shaking his head from side to side and grinning under his moustache when he disagrees with you or wants to avoid talking about something. So forget about discussing censorship, internal exile, or other sensitive subjects. He is not going to retell his story about how a thousand South Vietnamese POWs were brought North to impregnate a thousand widows in Ho Chi Minh’s natal village—even if this tale summarizes in one allegorical masterstroke the history of postwar Vietnam.

Ninh complains about the heat, and then he starts complaining about the Chinese, which is currently the number one topic in Vietnam. On April 30th—Vietnam’s national holiday for marking the unification of north and south Vietnam, the day you pick if you want to kick your enemy in the nuts and then spit in his eye—China moved a billion-dollar oil rig into Vietnam’s offshore waters and started drilling for oil. China surrounded the rig with an armada of ships and chased off any Vietnamese boats that dared to approach. The Chinese rammed Vietnamese coast guard vessels. They sank fishing boats. They fired water cannons that looked like medieval dragons spouting blue flames. As silly as these dragon boats may have looked, they proved quite effective at destroying electrical gear on the Vietnamese boats that were forced to flee.

Following this Chinese aggression, thirty thousand Vietnamese rose up in protest and started sacking Chinese textile factories around Saigon. Mobs burned at least fifteen companies and damaged another five hundred before police got the area locked down. Speculation abounds about the cause of these riots. They were orchestrated by government agents or by anti-government agents or by criminal gangs or by the Chinese themselves, since the looted factories turned out to be owned by Taiwanese and Koreans.

“We are experts on China,” says Ninh. “We just don’t talk about it. They are always smiling, but their smile is dangerous. They will be the nightmare of the world. By 2030, China will be far stronger than the United States. Our civilization will be threatened. I’m pessimistic. I see no light at the end of the tunnel,” he says, using a phrase employed by Richard Nixon during the Vietnam war. “I see only darkness,” Ninh says. “The younger generation should prepare. I feel a black cloud coming. Danger is approaching.”

Now that the red wine is gone, Ninh fills his glass with white and urges us to eat more egg rolls. Our host has a thatch of salt and pepper hair, now more salt than pepper, and a Fu Manchu moustache that gives his face the look of a window shuttered behind Venetian blinds. Wearing dark slacks and a white, short-sleeved shirt, he has kicked off his sandals and is cooling his feet on the linoleum as he settles back in his chair to ponder the dark cloud floating over Vietnam. It is quiet out on the street, save for the occasional motorbike rolling down the lane, but Ninh tells us how, during the day, he hears a constant din from the loudspeaker attached to a pole outside his door. The Party directives and propaganda become increasingly strident around holidays, the worst being April 30th, which commemorates the day in 1975 that Bao Ninh and his fellow soldiers captured Saigon.

“They talk about the old victories over and over again,” he says. “Even as a soldier I don’t like it. It’s like telling a beautiful girl she’s beautiful. She already knows she’s beautiful; so all you’re doing is annoying her. Next year, which marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the war, it’s going to be really annoying,” he says.

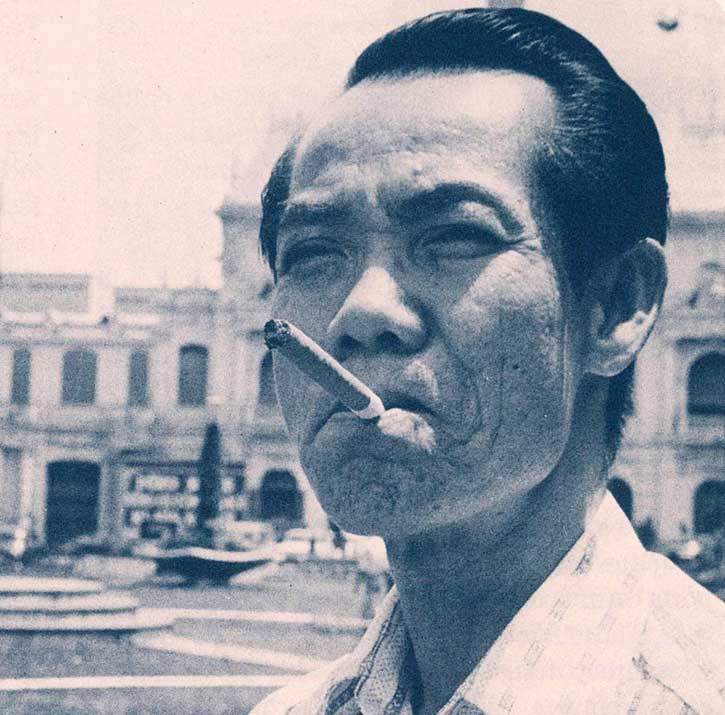

I have given Ninh a copy of my newly-published book. He keeps fingering it, flipping through the pages, stopping now and then to study a passage. “I don’t like intelligence agents and the police,” he says. “Maybe I’ll like them better after I read this.”

Ninh pours himself another glass of wine. “I never met Pham Xuan An,” he says. “He was a big general. I was just a soldier. Now that the government has made him a hero, they’ve started telling young people to act like him, which is really stupid. It’s like telling American teenagers they should grow up to be like Lyndon Johnson.”

Ninh stops to read the opening paragraph. “This is how you can tell if a translation is worth reading,” he says. “It looks pretty good.” Later he will send me an email praising the book and telling me how much he enjoyed reading it, even with the missing passages.

Ninh’s face is animated by the thick eyebrows that sweep over his black eyes. He windmills his hands through the air and slaps the back of his head. Then he pushes his hands in front of him like a surf swimmer heading for deep water. “The more we understand the Chinese the more we fear them,” he says. “Hitler was able to come to power because he was helped by Britain and France. They took care of him. The same is true with the United States and China. The Americans built up China’s industrial capacity. You moved your factories to China. You made the Chinese strong by doing business with them, but this strategy is going to fail in the end, just like it failed with Hitler.”

I nudge the conversation back to writing. “We have to follow the Communist Party line,” he says about censorship in Vietnam. “Every writer knows this. You’re hired for a reason; so don’t talk back. If you don’t accept the censorship system, then don’t be a writer.”

“They want to make Pham Xuan An into a political commissar,” he says. “This is why they censored your book. A good intelligence agent is like a priest. He keeps his secrets to himself.” The secrets of Pham Xuan An could be revealed only after the war and only selectively, after having been shaped into a heroic tale.

“For Vietnamese readers, a book without any cuts is a surprise,” says Ninh. “People will know where your book was cut. I prefer to read the printed version, but young people will go online to learn what you really wrote. This is becoming second nature for us, and soon we won’t have any printed books at all.”

He tells me he is writing a new novel, but he won’t say what it’s about. “We have to work quietly and not talk about it to anyone,” he says. “My time is over. I just write. I don’t publish.”

I ask him what Vietnamese writers I should be reading. “There is no generation of young writers,” he says. “There are just some individuals, one or two that I read.”

Next we talk about the movie that was being made of his novel. Film rights to The Sorrow of War were sold to a young American producer, Nicholas Simon, who also wrote the screenplay, but the project unraveled a few days before filming was to start. “We didn’t understand each other,” says Ninh. “We’re both stubborn people. He was young. He knew nothing about Vietnam. The script was so far from reality that it was ludicrous. I kept editing it, but it never got better. I yelled at him in Vietnamese. He yelled at me in English. The translator cried. Finally, the main investor, who was a friend of mine, fled after seeing our inability to get along. A movie has to be easy. My book is too hard to make into a movie.”

Before saying goodnight, Bao Ninh offers his final word on the subject of censorship. “Some guy who grew up as a peasant has the right to mess with your work? No one has the right to censor a book. When politics enters the room, ethics flies out the door. Other countries have laws protecting writers. In Vietnam, we have nothing. There are no rules to follow. The politicians make the rules.”

Part 12: The struggle