10 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

To date, there have been six books written about Pham Xuan An, three in Vietnamese, one in French, and two in English. The self-described “official” biography, Perfect Spy, was published in the United States in 2007 and translated into Vietnamese a year later. “We turned the book red,” said someone knowledgeable about its publication in Vietnam. In other words, Vietnamese censors brightened the patriotic color in an already selective portrait of a national hero.

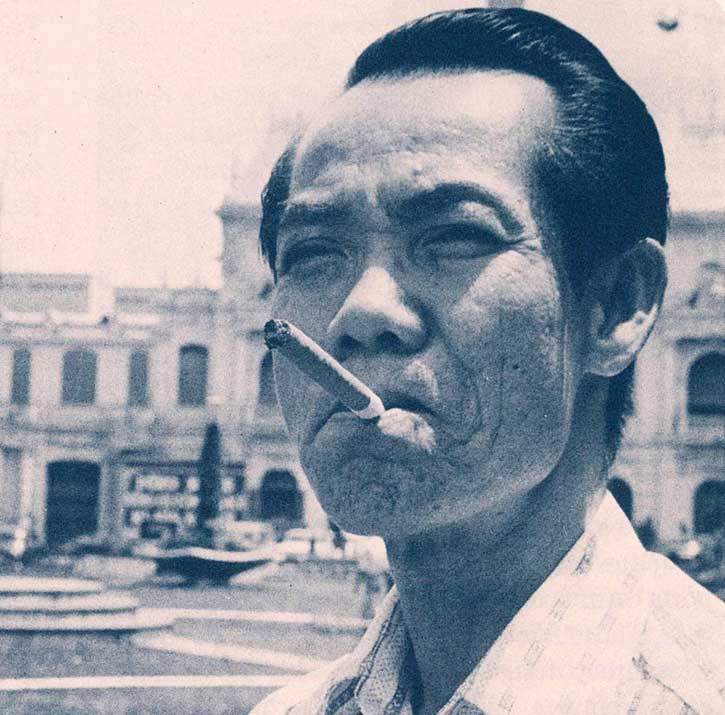

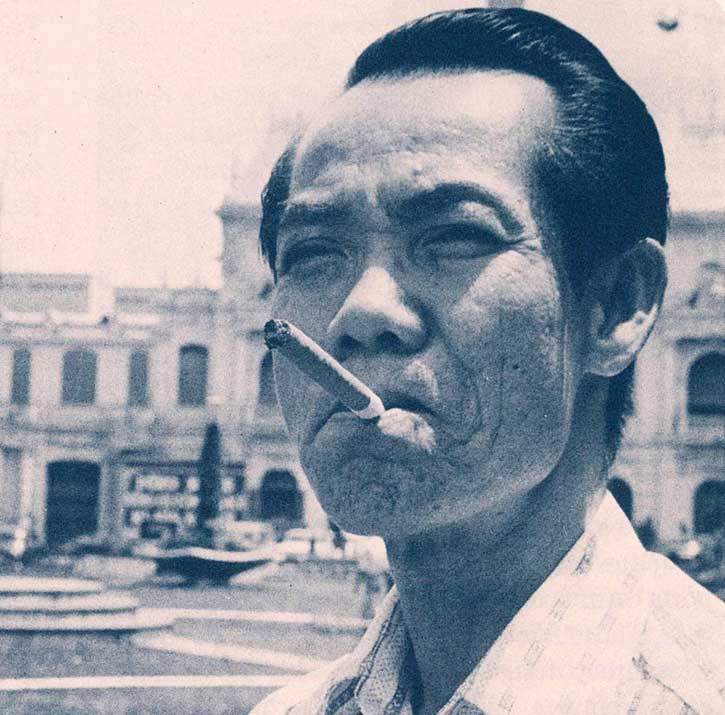

From the title alone, one understands that Perfect Spy portrays Pham Xuan An as a Vietnamese nationalist and patriot. The book also claims that he retired happily at the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. The problem with this narrative is that appears not to be true. Every spy has a cover, the life he hides behind while leading a double existence or, in Pham Xuan An’s case, a quadruple existence, since, at one time or another, he worked for the French Deuxième Bureau, the CIA, and both the South and North Vietnamese intelligence agencies. His spying for the French was limited to moonlighting as a censor at the Post Office, trimming Graham Greene’s dispatches to Paris Match. His work for the Americans included his being trained in psychological warfare in the1950s by Edward Lansdale and other CIA operatives.

His work for South Vietnamese intelligence, where he served as right-hand man to spy chief Tran Kim Tuyen, supposedly ended in 1962, when Tuyen was cashiered in a failed coup attempt. But An kept in touch with Tuyen, who remained an inveterate “coup cooker.” He took him food and medicine while the master spy was under house arrest (undoubtedly passing messages during these exchanges). Then An did Tuyen one final service. He saved his life. The famous 1975 photo of the last U.S. helicopter lifting off from the roof of 22 Gia Long Street shows a rickety ladder leading up to the chopper. The last man climbing that ladder, thanks to the intercession of his former right-hand man, is Tran Kim Tuyen. Why did An help the long-time head of South Vietnamese intelligence escape from the communists? “I knew I would be in trouble,” An told me. “This was the chief of intelligence, an important man to capture, but he was my friend. I owed him.” Who knows what bonds of loyalty were served or embarrassing questions avoided as Tuyen flew off to exile in England.

For twenty years An maintained his cover as a journalist, but when this was blown at the end of the Vietnam war, he developed a second cover—that of a happily-retired global strategist who spent his days shooting the breeze with Western journalists and other visitors. Recently I saw film footage of An being interviewed in 1988 by Vietnamese refugee and Hollywood actress Tiana Silliphant. Tiana was gathering material for her documentary From Hollywood to Hanoi. While being interviewed, An sits casually on the front steps of his house, with not one but two German shepherds guarding his back. Tiana asks him straight away about the people he betrayed and the friends who died as a result of his spying. An goes bug-eyed and shifty. One sees him making up his answers on the spot, beginning to spin the story that will develop into his second cover. “I retired from the military a few weeks ago,” he says. “I never betrayed anyone.”

An is on record saying that he retired from the military in 1988. But he is also on record saying that he retired in 2002 and again in 2005. This is when a visitor noticed a large, flat-panel TV in his living room, with a card attached saying that the TV was a retirement present from his “friends” in Tong Cuc II—Vietnamese military intelligence. It is more likely that An never retired, that he remained a member of the intelligence services until the day he died. Under his first cover, as a journalist, he worked as a spy from the 1950s until the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. Under his second cover, as a retired strategist, he worked as a spy for another thirty years—even longer than his first career. What he did as an intelligence agent in active service remains unknown, but he undoubtedly wrote reports on his visitors and offered the kind of political analysis for which he was famous. With his humorous quips about how the communists had failed to “reeducate” him, An deflected any suspicions that he was still working as a spy. This aspect of his life was only revealed after his death, when General Nguyen Chi Vinh, who was then head of Tong Cuc II, delivered the oration at An’s funeral. General Vinh’s speech about An’s “extraordinary military achievements,” accomplished while living “in the bowels of the enemy,” included the list of An’s military medals, each of which tells an important story about his life.

In a glancing reference, Perfect Spy mentions that Pham Xuan An won eleven military medals. He actually won sixteen military medals, and six of these medals were awarded after 1975. Fourteen of the total number of medals, and four of the medals awarded after 1975, are combat medals. These are given not for strategic analysis, but for specific military actions. An won medals for his tactical assistance in battles ranging from Ap Bac in 1963 and Ia Drang in 1965 to the Tet Offensive in 1968 and on to the Ho Chi Minh Campaign that ended the war in 1975. What An did to win four military medals after 1975 remains unknown.

To undercount An’s medals, ignore their significance, and overlook the fact that many of these medals were awarded after 1975 is part of the campaign to make Pham Xuan An a “perfect spy,” a benign figure, like Ho Chi Minh, removed from the staggering violence that marked Vietnam’s anti-colonial wars. In Perfect Spy other aspects of An’s career have been trimmed or suppressed. Softened in the narrative are his criticisms of communist incompetence and corruption, his acerbic comments about Russian influence in Vietnam, his attacks on Chinese meddling in the nation’s affairs, his jokes about having been “reeducated” in 1978, and his opposition to the Chinese-influenced clique that currently runs the country. Also downplayed or ignored are the details that explain why An’s wife and four children were sent to the United States in 1975 and then, a year later, recalled to Vietnam. In the version crafted for public consumption, and as reported by An’s “official” biographer, he remained in Saigon at the end of the war to care for his sick mother. In fact, the Vietnamese intelligence services planned to send An to the United States, where he would continue spying for the communists. Only when this plan was overruled by the Politburo was An forced to stay in Vietnam and recall his family. This information about An’s post-war activities reveals how Vietnam intended—and undoubtedly succeeded—in placing spies in the United States at the end of the war. It also reveals a rift between the country’s intelligence services and the Politburo, a rift that Vietnamese propaganda would like to paper over with a story about a sick mother.

Once the shadows are put back into Pham Xuan An’s life, the censors are bound to object to his less-than-perfect narrative. In fact, they will spend five years rewriting the story and struggling to get it as close as possible to the official version. Nha Nam’s gambit was flawed. Because one book about Pham Xuan by a westerner had been translated and published in Vietnam did not mean that a second book would follow easily. In fact, as we learned recently, even the “red” version of An’s life had been a hard sell. This was revealed in a State Department cable of September 2007, which was released by Wikileaks in 2011. The cable, by a consular official in Ho Chi Minh City, describes how the Vietnamese translation of Perfect Spy, although it was published by a government-owned company, was nearly pulped at the last minute by censors in the Ministry of Public Security. They objected “to the numerous quotes from Pham Xuan An lamenting that Vietnam had simply traded one overlord for another—the Soviet Union—and his criticism of post-war policies.” The editors were in trouble for “supporting the publication of a book in which one of the country’s most renowned heroes unleashes broadside attacks on post-war GVN policy and the closed nature of Vietnamese society.” According to the consular memo, “the pro-reform faction within the GVN” got “the upper hand” over “the counter-reform faction” only when the president of Vietnam himself gave his approval to publish the book.

One can see in these stories about Vietnamese censorship how the rule of law has been replaced by the rule of the jungle. Powerful people will do everything possible to protect their prerogatives. I am alarmed by these stories, but many people yawn when I talk to them about censorship in Vietnam. “What do you expect?” they say. “There’s nothing surprising here.” Even my Vietnamese friends have succumbed to fatalism and a strange belief that they can read around corners. “I can tell where a book has been cut,” novelist Bao Ninh assured me. “We know what’s missing. We just can’t talk about these things.”

It is hard to argue against censorship in the face of rampant cynicism, but a worthy effort was made recently by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen. In an essay written for Index on Censorship in 2013, Sen chastises his native India for thinking that they should emulate China, which appears to be the model for how authoritarian governments can swap personal freedom for economic growth. Sen argues the opposite position, that “press freedom is crucially important for development.” Free speech has “intrinsic value,” he says. It is “a necessary requirement of informed politics.” It gives “voice to the neglected and disadvantaged,” and it is crucial for “generating new ideas.” China appears to be doing quite nicely at the moment, but Sen—an economist who did his award-winning work on the theory of famine—reminds us what can happen when propaganda replace news.

“There is an inescapable fragility in any authoritarian system,” he writes. The last time this phenomenon revealed itself in China, during the botched agrarian reforms of the Great Leap Forward, the country suffered one of the world’s most devastating famines. “The Chinese famine of 1959-1962 … killed at least 30 million people, when the regime failed to understand what was going on and there was no public pressure against its policies, as would have arisen in a functioning democracy.”

“The policy mistakes continued throughout these three years of devastating famine,” says Sen. “The information blackout was so complete with censorship and control of the state media that government itself came to be deceived by its own propaganda and believed that the country had 100 million more metric tons of rice than it actually had. Eventually, Chairman Mao himself made a famous speech in 1962, lamenting the ‘lack of democracy,’” a lack that, in this case, had proved lethal. India and other parts of the world might be tempted to emulate China, in light of its double-digit growth, but people would be foolish, says Sen, to adopt the anti-democratic measures that weaken totalitarian systems and make them susceptible to believing their own lies.

Part 8: The habits of war

This seventh installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 10, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

The web is where Vietnamese literature has moved, as the grey net of police surveillance, fines, exile and prison is cinched ever more tightly around the country’s journalists, bloggers, artists, musicians, writers and poets

|

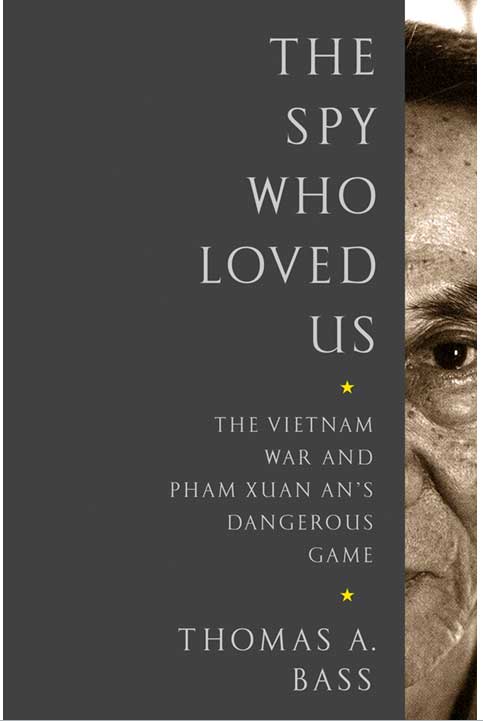

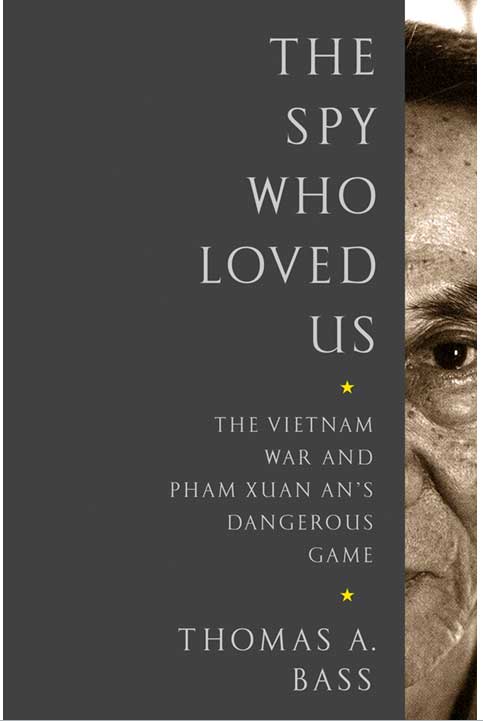

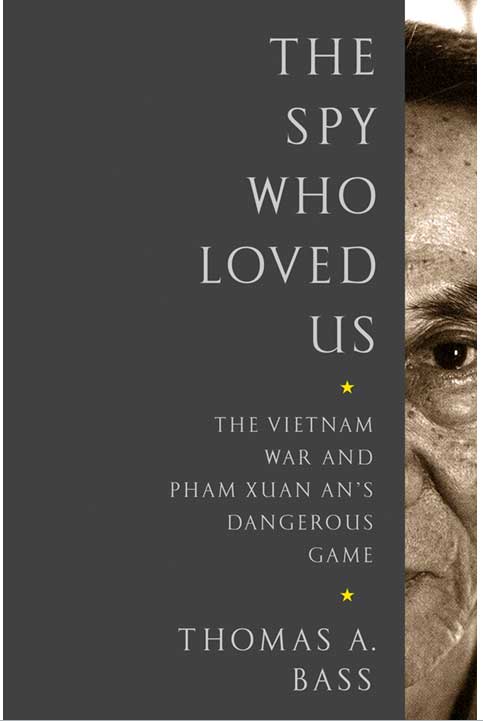

About Swamp of the Assassins

Thomas Bass spent five years monitoring the publication of a Vietnamese translation of his book The Spy Who Loved Us. Swamp of the Assassins is the record of Bass’ interactions and interviews with editors, publishers, censors and silenced and exiled writers. Begun after a 2005 article in The New Yorker, Bass’ biography of Pham Xuan An provided an unflinching look at a key figure in Vietnam’s pantheon of communist heroes. Throughout the process of publication, successive editors strove to align Bass’ account of An’s life with the official narrative, requiring numerous cuts and changes to the language. Related: Vietnam’s concerted effort to keep control of its past

|

About Thomas Bass

Thomas Alden Bass is an American writer and professor in literature and history. Currently he is a professor of English at University at Albany, State University of New York.

|

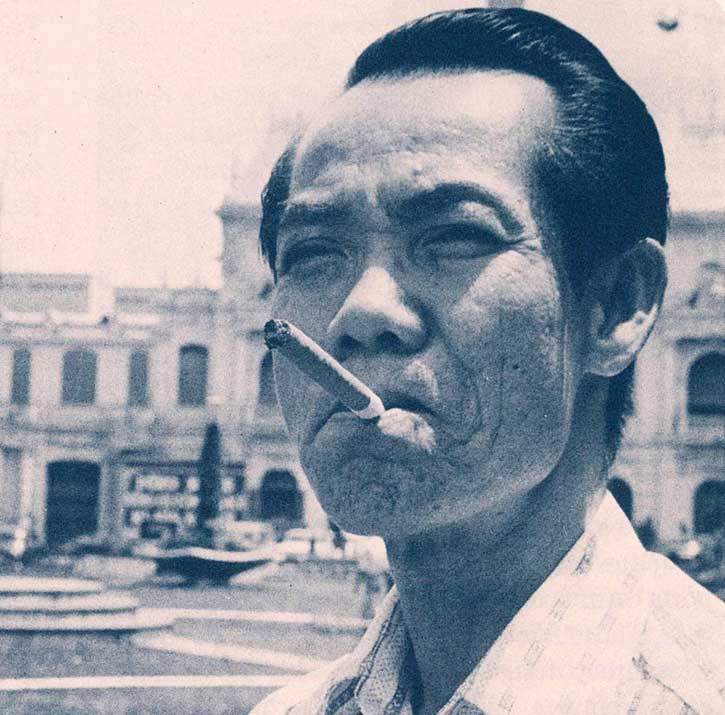

About Pham Xuan An

Pham Xuan An was a South Vietnamese journalist, whose remarkable effectiveness and long-lived career as a spy for the North Vietnamese communists—from the 1940s until his death in 2006—made him one of the greatest spies of the 20th century.

|

Contents

2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country

|

Sometime in March 2014—no one can tell me for sure, and, in fact, the book’s publishing license is not issued until May 2014—a Vietnamese translation of The Spy Who Loved Us appears in Hanoi. By this point, even the title of my book has been censored. It has been reduced to Z.21, a code name for Pham Xuan An, as if the book itself, like its hero, will try to travel unnoticed through the shifting terrain of Vietnam’s culture wars.

I had been sent a final list of censored passages and was settling down to review these cuts when I received the email telling me that the book had been published. This was a breach of contract, but I decide not to press the point, because I am now contractually free, in six months, to release my own uncensored version on the web. The web is where Vietnamese literature has moved, as the gray net of police surveillance, fines, exile, and prison is cinched ever more tightly around the country’s journalists, bloggers, artists, musicians, writers, and poets—yes, even Vietnam’s poets can get in trouble, as I soon learn on a visit to Vietnam.

I use the minor stir occasioned by my book’s publication (including a cover story in Communist Youth magazine) to schedule a trip to Southeast Asia. I want to meet the censors with whom I had been sparring for the past five years, or at least the ones who will step forward and talk to me. I arrive on the night flight from Paris to Hanoi at the end of May and begin swimming through a miasma of tropical heat and humidity, before taking refuge in the Church Hotel, near St. Joseph’s cathedral in Hanoi’s old quarter. From here I schedule a meeting with Nguyen Viet Long, my original editor at Nha Nam. I also schedule meetings with Nguyen Nhat Anh and Vu Hoang Giang, chairman and vice-chairman of the company. Later, I learn that two other people who played a role in this affair are willing to talk to me. They include Nguyen The Vinh, editor at Hong Duc, the state-owned publishing company that produced the final list of passages to be censored and then issued my publishing license. Also willing to meet me is Duong Trung Quoc, an historian and elected member of Vietnam’s National Assembly, who seems to have negotiated the political deals required to get my book—or at least a version of my book—published in Vietnam.

The translator of Z.21 is a Hanoi journalist named Do Tuan Kiet. Judging from his work (unfortunately, he is out of town during my visit), Kiet speaks Vietnam’s dominant northern dialect, which today is larded with Marxist-Leninist terms borrowed from the Chinese. This language grates on the ears of southern Vietnamese. It is not the language spoken by Pham Xuan An, the hero of my book, and, in fact, An mocked this speech. He dismissed the ten months he spent in 1978 at the Nguyen Ai Quoc National Political Academy outside Hanoi as “reeducation”—a failed attempt to teach him this jargon. “I had lived too long among the enemy,” he said. “They sent me to be recycled.”

After my book was translated, Long, my editor, began the serious work of censoring it. Over the years, as he tried to secure a publishing license, more and more changes were made to the text, as one state-owned company after another rejected the book. By the end, I imagine the project had grown ripe with the odor of danger. It was not something one wanted to touch if you valued your career as an editor at Police newspaper or the Ministry of the Interior. Long himself must have begun to look a bit suspicious. Then he left trade book publishing and went to work editing math texts for school children.

Long and I have agreed to meet at my hotel. He rings the bell and enters the room nervously. He sits on the edge of the sofa, apologizes for being late, and finally agrees to drink a beer. In his 50s, with dark hair framing his square head, Long is dressed in the uniform of a Vietnamese cadre: owlish eyeglasses, short-sleeved white shirt with pen in the front pocket, metal watch flopping around his wrist, gray slacks, and sandals. He glances around him, as if he is looking for listening devices, and begins answering my questions with the kind of guarded indirection one develops in a police state.

Trained as an engineer in the former Soviet Union, Long’s specialty was cybernetics or control systems for nuclear reactors, particularly the nuclear reactor in Dalat that the victorious North Vietnamese seized from the retreating Americans in 1975. A graduate of the Moscow Power Engineering Institute, Long taught himself English during his five years in Russia.

After chatting about his move from cybernetics to publishing, we begin talking about my book. “There was a serious battle to edit your book,” he says. “I was caught in the middle, being pressured by the author and my superiors. The regime has declared this a sensitive book. You can get in a lot of trouble for handling this kind of project improperly. That’s all I can tell you.”

“By law, there are no private publishing houses in Vietnam,” he says. “So Nha Nam has to ally itself with a state-run publisher every time it releases a book. We took your book to a lot of publishers, and they all turned it down. Finally, Hong Duc agreed to give it a publishing license. They’re a powerful publisher.”

“Why are they powerful?” I ask.

Long laughs nervously. “Let’s just say they’re powerful. That’s all I can tell you.” Later I learn that Hong Duc is run by Vietnam’s Ministry of Information and Communication, one of the country’s major censors.

“What about the material that was cut from the book?” I ask.

“The translator translated the entire book,” he says. “Then we removed the passages that had to be removed. We couldn’t leave them untouched. Publishing your book was a very hard process. A lot of subjects had to be censored, and there was no choice about removing them.”

When I ask for examples, he mentions Colonel Bui Tin, who defected to France in 1990 to protest Vietnam’s lack of democracy, and General Giap, who, before his death in 2013, wrote letters opposing China’s influence in Vietnam. “Nothing about these affairs can be written,” he says. “Everyone knows about them, but you can’t get a publishing permit if these things are in your book.”

“How do you know what has to be censored?”

“We must know. We observe. Maybe some people have different ideas, but we know what we’re supposed to do. A lot of it depends on timing,” he says. “We published a book by the Dalai Lama against China. Then, when the authorities noticed what we had done, we were forbidden from publishing more books by the Dalai Lama. In general, we couldn’t publish anything bad about China. For example, the 1979 border war between Vietnam and China was something we weren’t allowed to write about.”

Long has a nervous cough at the back of his throat. He declines a second beer. Again he glances around the room, finding nothing to make him look less glum.

“The censorship is often silent,” he says. “Without formally being banned, all the books that have been published can suddenly disappear from the shelves.”

“Publishing your book was a very hard process,” he says again. “It was the most difficult book for me.”

I ask Long if he is a member of the Communist Party. He is not a Party member, but his brother is. “There are political benefits from joining the party,” he says. “It helps you rise in state-run institutions.”

He declines another beer and says it’s time for him to retrieve his motorbike and ride home. He congratulates me on the publication of my book.

“It is not really my book,” I say, mentioning the four hundred passages that were cut.

“Four hundred is not so many,” he says. “We have an expression in Vietnamese, ‘If the head goes through, the tail will follow.’ In the next edition, maybe some of these passages will be restored.”

As Long slips out the door, he looks worried about having said too much during our brief encounter. I wish him well in his new job. “The pay is better,” he assures me.

Part 6: Vietnamology

This fifth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 6, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

What the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses

|

About Swamp of the Assassins

Thomas Bass spent five years monitoring the publication of a Vietnamese translation of his book The Spy Who Loved Us. Swamp of the Assassins is the record of Bass’ interactions and interviews with editors, publishers, censors and silenced and exiled writers. Begun after a 2005 article in The New Yorker, Bass’ biography of Pham Xuan An provided an unflinching look at a key figure in Vietnam’s pantheon of communist heroes. Throughout the process of publication, successive editors strove to align Bass’ account of An’s life with the official narrative, requiring numerous cuts and changes to the language. Related: Vietnam’s concerted effort to keep control of its past

|

About Thomas Bass

Thomas Alden Bass is an American writer and professor in literature and history. Currently he is a professor of English at University at Albany, State University of New York.

|

About Pham Xuan An

Pham Xuan An was a South Vietnamese journalist, whose remarkable effectiveness and long-lived career as a spy for the North Vietnamese communists—from the 1940s until his death in 2006—made him one of the greatest spies of the 20th century.

|

Contents

2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country

|

The process by which censorship works in Vietnam is described by Vietnamese reporter Pham Doan Trang in a blog post released in June 2013 by The Irrawaddy Magazine. Trang explains how, every week, the Central Propaganda Commission of the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hanoi and the Commission’s regional officials in Ho Chi Minh City and elsewhere throughout the country “convene ‘guidance meetings’ with the managing editors of the country’s important national newspapers.”

“Not incidentally, the editors are all party members. Officials of the Ministry of Information and Ministry of Public Security are also present. …At these meetings, someone from the Propaganda Commission rates each paper’s performance during the previous week—commending those who have toed the line, reprimanding and sometimes punishing those who have strayed.”

Instructions given at these meetings to the “comrade editors and publishers,” sometimes leak into the blogosphere (the online forums from which the Vietnamese increasingly get their news). Here one learns that independent candidates for political office, such as actress Hong An, are not be mentioned in the press and that dissident activist Cu Huy Ha Vu, who is charged with “propagandizing against the state,” should never be addressed as “Doctor Vu.” Also buried are reports on tourists drowning in Halong Bay, Vietnam’s decision to build nuclear power plants, and Chinese extraction of bauxite from a huge mining operation in the Annamite Range.

The weekly meetings are secret and further discussions throughout the week are conducted face-to-face or by telephone. “Because no tangible evidence remains that … the press was gagged on such and such a story, the officials of the Ministry of Information can reply with a straight face that Vietnam is being slandered by ‘hostile forces,’” Trang says. These denials were strained when a secret recording of one of these meetings was released by the BBC in 2012.

The Propaganda Department considers Vietnam’s media as the “voice of party organizations, State bodies, and social organizations.” This approach is codified in Vietnam’s Law on the Media, which requires reporters to “propagate the doctrine and policies of the Party, the laws of the State, and the national and world cultural, scientific and technical achievements” of Vietnam.

Trang concludes her report with a wry observation. “Vietnam does not figure among the deadlier countries to be a journalist,” she says. “The State doesn’t need to kill journalists to control the media, because by and large, Vietnam’s press card-carrying journalists are not allowed to do work that is worth being killed for.”

Another person knowledgeable about censorship in Vietnam is David Brown, a former U.S. foreign service officer who returned to Vietnam to work as a copy editor for the online English language edition of a Vietnamese newspaper. In an article published in Asia Times in February 2012, Brown describes how “The managing editor and publisher [of his paper] trooped off to a meeting with the Ministry of Information and the Party’s Central Propaganda and Education Committee every Tuesday where they and their peers from other papers were alerted to ‘sensitive issues.’”

Brown describes the “editorial no-go zones” that his paper was not allowed to write about. These taboo subjects include unflattering news about the Communist Party, government policy, military strategy, Chinese relations, minority rights, human rights, democracy, calls for political pluralism, allusions to revolutionary events in other Communist countries, distinctions between north and south Vietnamese, and stories about Vietnamese refugees. The one subject his paper is allowed to cover is crime, and the press is not toothless in Vietnam, Brown says. In fact, journalists can prove quite useful to the government by exposing low-level corruption and malfeasance. “To maintain their readerships, they aggressively pursue scandals, investigate ‘social evils’ and champion the downtrodden. Corruption of all kinds, at least at the local level, is also fair game.”

Another expert on censorship in Vietnam is former BBC correspondent Bill Hayton, who was expelled from Vietnam in 2007 and is still banned from the country. Writing in Forbes magazine in 2010, Hayton describes the limits to political activity in Vietnam, where Article 4 of the Constitution declares that “The Communist Party of Vietnam, the vanguard of the Vietnamese working class, the faithful representative of the rights and interests of the working class, the toiling people, and the whole nation, acting upon the Marxist-Leninist doctrine and Ho Chi Minh thought, is the force leading the State and society.” In other words, what the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses. “There is no legal, independent media in Vietnam,” says Hayton. “Every single publication belongs to part of the state or the Communist Party.”

Lest we think that Vietnamese culture is frozen in place, Trang, Brown, Hayton, and other observers remind us that the rules are constantly changing and being reinterpreted. “Vietnam … is one of the most dynamic and aspirational societies on the planet,” says Hayton. “This has been enabled by the strange balance between the Party’s control, and lack of control, which has manifested itself through the practice of ‘fence-breaking,’ or pha rao in Vietnamese.” So long as you “don’t confront the Party or pry too deeply into high-level corruption, editors and journalists can get along fine,” he says.

In certain circumstances, even journalists who pry more deeply can get along fine, depending on who is controlling the news leaks and for what end. This process of controlled leaks is described by another observer of censorship in Vietnam, Geoffrey Cain. In his master’s thesis, completed in 2012 at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, Cain writes that the Communist Party in Vietnam uses journalists and other writers as an “informal police force.” They help the central government keep regional officials in line, limit their bribe taking, and patrol aspects of public life that otherwise might remain in the shadows. This represents “soft authoritarianism,” which is characterized by “a series of elite actions and counter-actions marked by ‘uncertainty’ as an instrument of rule.” What is often described in Vietnam as a battle between “reformers” and “conservatives” is actually the method by which an increasingly market-oriented society can be “simultaneously repressive and responsive.” In this interpretation, journalists and bloggers lend themselves to the “informal policing” of free-market profiteers.

The “legal” mechanisms for the arrest of journalists and bloggers who overstep the boundaries, or accidentally get caught on the wrong side of shifting rules, include Article 88c of the Criminal Code, which forbids “making, storing, or circulating cultural products with contents against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” and Article 79 of the Criminal Code, which forbids “carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration.” Other grounds for arrest range from “tax evasion” to “stealing state secrets and selling them abroad to foreigners.” (This was the charge leveled against novelist Duong Thu Huong when she mailed one of her book manuscripts to a publisher in California.)

Other repressive measures lie in the Press Law of 1990 (amended in 1999), which begins by declaring, “The press in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam constitutes the voice of the Party, of the State and social organizations” (Article 1). “No one shall be allowed to abuse the freedom of the press and freedom of speech in the press to violate the interests of the State, of any collective group or individual citizen” (Article 2:3). Then there is the Law on Publishing of 2004, which prohibits “propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” the “spread of reactionary ideology,” and the “disclosure of secrets of the Party, State, military, defense, economics, or external relations.”

On goes the list of laws and regulations through various decrees and “circulars,” including Decree Number 56, on “Cultural and Information Activities,” which forbids “the denial of revolutionary achievements,” Decree Number 97, on “Management, Supply, and Use of Internet Services and Electronic Information on the Internet,” which forbids using the internet “to damage the reputations of individuals and organizations,” Circular Number 7, from the Ministry of Information, which “restricts blogs to covering personal content” and requires blogging platforms to file reports on users “every six months or upon request,” and the 2012 draft Decree on “Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Information on the Network,” which requires foreign-based companies that provide information in Vietnamese “to filter and eliminate any prohibited content.”

This 2012 draft Decree was codified the following year as Decree 72, which outlaws the distribution of “general information” on blogs, limiting them to “personal information” and making it illegal for individuals to use the internet for news reporting or commenting on political events. Condemning this statute as “nonsensical and extremely dangerous,” Reporters Without Borders, in an August 2013 press release, said that Decree 72 could be implemented only with “massive and constant government surveillance of the entire internet. …This decree’s barely veiled goal is to keep the Communist Party in power at all costs by turning news and information into a state monopoly.”

Vietnam has borrowed many of these techniques for monitoring the internet from China, its neighbor to the north. According to PEN International, China has imprisoned dozens of authors, including Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. Like China, Vietnam falls near the bottom in rankings of press freedom. Freedom House calls Vietnamese media “not free.” In 2014, Reporters Without Borders ranked Vietnam 174 out of 180 countries in press freedom. (It fell between Iran and China.) In 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists ranked Vietnam as the world’s fifth worst jailer of reporters, with at least eighteen journalists in prison. Recently, a draconian crackdown against bloggers and anti-Chinese protestors sent dozens more to jail, for terms as long as twelve years. Pro-democracy and human rights activists, writers, bloggers, investigative journalists, land reform protestors, and whistleblowers are all being swept up in Vietnam’s totalitarian dragnet.

Part 5: Literary control mechanisms

This fourth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 5, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

In June 2012, I receive an email from Thu Yen notifying me that The Spy Who Loved Us (or whatever the book is going to be called) has finally been approved for publication. Lao Dong (Labor) Publishing House, owned by Vietnam’s Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs, has stepped forward as our co-publisher. As a hex against other, less powerful censors, Lao Dong’s name will appear on the title page. The deal involves certain concessions, Yen admits. “After a very long time of applying for publishing permission, we finally got a positive result from Lao Dong (Labor) Publishing House,” she writes. “In order for your book to be published, there are cuts and changes that cannot be otherwise. However, the good points are that they edited rather well in terms of Vietnamese language in writing and literature.”

No page proofs are sent with her email. Yen offers instead a description of the censored text. “Given the highly sensitive content of your book, I do hope you can see these changes in the most supportive aspect, as necessary for your book to come to our readers.”

Attached to Yen’s email is a twelve-page document listing no fewer than three hundred and thirty three additional cuts to the book. Sentences, paragraphs, and entire pages have disappeared. The cuts begin with the title and carry through to the final acknowledgments. Historical facts are airbrushed out of the text and so, too, are various people. Vo Nguyen Giap, the great Vietnamese general who won the battle of Dien Bien Phu, is no longer a quotable source. Colonel Bui Tin, who accepted the surrender of the South Vietnamese government in 1975, has been scrubbed from the text and even from the acknowledgments. Scenes describing Pham Xuan An’s interaction with the Party, the military, the Chinese, and the police have all hit the cutting room floor. Forbidden also are any attempts at cracking a joke or being the least bit ironic.

“You can’t write the truth in Vietnam,” says one of my advisers, a former professor of literature who is now living in the United States. “My country is lost to lies. Your book had a human being at the center of it, but now it is stripped of all the details that made the story specific and compelling.

“The communists want the words to come out of your mouth,” she says. “Their official propaganda will look more authentic if it is authored by a Westerner. You are their tool. You can protest and negotiate what look to be small concessions, but in the end, they are going to win. They always win.

“Even the language in your book is now ugly,” she says. “It is opaque rather than clear. Many terms have been borrowed from the Chinese. Other words are what the French call langue de bois, bureaucratic jargon. The communists think they are superior when they use these words. They want to control everything, even your thoughts.”

“There is so much the censors don’t like, they just cut, cut, cut,” she says, after comparing the Lao Dong version of my book to Mr. Long’s manuscript. “I get a big headache just looking at this text.” Pham Xuan An is not allowed to “love” America or the time he spent studying journalism in California. He is only allowed to “understand” America. His quip that he never wanted to be a spy and considered it the “the work of hunting dogs,” is gone. His claim that he was born at a tragic time in Vietnamese history, with betrayal in the air, is cut. The Gold Campaign organized by Ho Chi Minh in 1946, when he solicited contributions for a bribe large enough to induce the Chinese army to retreat from northern Vietnam, is erased.

Pham Xuan An’s family is not allowed to have “migrated from north Vietnam to the south.” Nor is he allowed to have participated in the nam tien. This is the historic southward march of the Vietnamese, taking place over hundreds of years, as they worked their way down the Annamite Cordillera, occupying territory formerly held by Montagnards, Chams, Khmers, and other “minority” people. Praise for French literature is gone. He is not allowed to say that France created the map of modern Vietnam. His description of communism as a utopian ideal, unattainable in real life—cut. His praise of Edward Lansdale, as the great spy from whom he learned his tradecraft—cut. Throughout the text, North Vietnamese aggression is played down, South Vietnamese barbarism played up. The communists are always in the vanguard, the people always happily following. Pham Xuan An’s attempt to distinguish between fighting for Vietnamese independence and fighting for communism–cut.

We have only got to page thirty-eight, when my friend says, “They want to kill this book. They don’t like it at all.” Discussions of communist land campaigns and collective ownership—cut. The communists are no longer responsible for ambushing and killing Pham Xuan An’s former high school teacher in 1947. Instead, “there was an ambush” by unnamed agents. A description of John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert visiting Vietnam in 1951—cut. References to Vietnam’s offshore islands and oil fields, which are currently being fought over with the Chinese—cut. Claims that river pirate Bay Vien fought for the communists before switching sides—cut. “These people are getting more paranoid every day,” she says.

There is also a long list of errors in the translation, words that my Vietnamese editors have either misunderstood or refused to understand, words such as ghost writer, betrayal, bribery, treachery, terrorism, torture, front organizations, ethnic minorities, and reeducation camps. The French are not allowed to have taught the Vietnamese anything. Nor the Americans. Vietnam has never produced refugees. It only generates settlers. References to communism as a “failed god”—cut. Pham Xuan An’s description of himself as having an American brain grafted onto a Vietnamese body—cut. His analysis of how the communists replaced Ngo Dinh Diem’s police state with a police state of their own—cut.

The story of the first American casualty in the Vietnam war, OSS officer A. Peter Dewey, who was accidentally assassinated by the communists in 1945, is gone. Vietnamese army officers are written out of campaigns. The Tet Offensive is not allowed to be described as a military failure. Dogs are no longer barbecued alive. Sexual peccadilloes, mistresses, forced marriages—all disappear when communist officials are involved. Descriptions of Saigon in the weeks immediately following the end of the war, including food shortages and the tightening noose of state security—gone. Even the ban on cockfighting becomes unmentionable. That Boat People fled the country after 1975—cut. That Vietnam fought a war against Cambodia in 1978—cut. That Vietnam fought a war against China in 1979—cut. Pham Xuan An’s last wishes, that he be cremated and his ashes scattered in the Dong Nai River, have been cut. (Instead, he received a state funeral with the eulogy delivered by the head of military intelligence.) By the time we get to the end of the book, entire pages of notes and sources have disappeared. So, too, has the index, where so many words would have had to somersault into their opposites.

“Thank God we have come to the end,” says my friend. “This has given me white hairs and nightmares.”

The Lao Dong manuscript presents a conundrum. How does one respond to something as nefarious as this? My advisors suggested two solutions. Kill the project, or work out a hostage trade. Nha Nam and Lao Dong will be allowed to proceed with publishing the book, but only in exchange for giving me an unlocked version of the manuscript that can be restored to its original form and published on the web.

To prepare for these negotiations, I review the contract I signed with Nha Nam three years earlier. The publisher will make only “slight modifications in the original text of the work,” and these modifications “shall not materially change the meaning or otherwise materially alter the text.” I ask my agent in New York to send notice to our subagent in Bangkok alerting Nha Nam that they are in breach of contract for substituting a work of propaganda for a translation.

Along with paying me for translation rights—a delay occasioned by “accidental oversight”—Nha Nam begins backtracking on the “cuts and changes that cannot be otherwise.” They had wanted to call the book “Perfect Spy,” but now Yen agrees to restore an earlier title that Mr. Long and I had negotiated. “This translation being censored is what both parties have seen from the beginning,” she writes to my agent in July 2012. “The extent to which the translation has been censored may have shocked the author (as well as us). But we are in here, all the time now, and we know the situation in our country. We have gone to seven different state-owned publishing houses, and, in the end, only Labor Publishing would give us a license, with cuts and changes.”

My canceling the publishing contract would be “the most easy-way-out-solution,” Yen concludes, but “this would be unfair to us and our honest intentions. We would be very disappointed,” she says.

My hostage negotiations are not going well either. Yen demands the right to censor the book on the web, thereby extending Vietnamese hegemony throughout the universe. Eventually she retreats to demanding a six-month delay between publication of the book in Vietnam and its release on the web. We also agree that a disclaimer will be printed on the copyright page saying, “This is a partial translation of The Spy Who Loved Us. Parts of the text have been omitted or altered.”

By the end of the year, when I have yet to receive a copy of the galleys to review and our publishing license is about to expire, Yen writes, “Why have you agreed to work with Nha Nam if you don’t trust your Vietnamese editor? Are we less trustworthy than your friends?” I imagine her lacquered nails scratching the keyboard as she types. “We would like no more opinions from outsiders. It is not professional.”

In June 2013 Yen sends me a note announcing that Nha Nam is trying to secure another publishing license (the last one having expired), and she hopes soon to be writing with good news. She admits that editors in Vietnam are “scared” of the project. The following week I receive a request from Yen to “friend” me on Facebook.

Part 4: Not worth being killed for

This third installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 4, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org