By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship completes publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Cyberspace will be the only space in Vietnam free of censorship |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

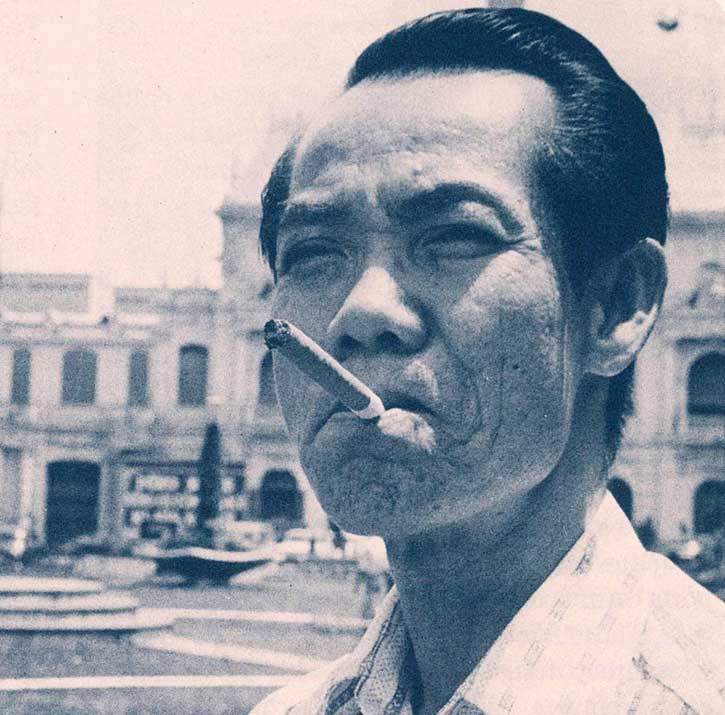

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

A few weeks after talking to Duong Thu Huong, I arrange another meeting with a writer driven into exile by Vietnam’s censors. This time, I travel to Berlin to meet Pham Thi Hoai. Born in 1960 in Hai Duong, east of Hanoi, Hoai studied archival science at Humboldt University in the former East Berlin. Then she began to write stories and novels and translate into Vietnamese the works of Kafka, Brecht, Tanazaki, Amado, and other writers. Combining the fastidiousness of the Germans with the fastidiousness of the Vietnamese, Hoai has long presided over Vietnam’s intellectual community-in-exile. For thirteen years, as producer, editor, writer, and translator, she ran talawas and its successor pro&contra, two electronic journals of culture and politics that were the key sites for anyone interested in learning what was really happening in Vietnam. From her exile on the Spree, forbidden from returning home to Vietnam, Hoai became the Sybil known for delivering the final word on her country’s benighted fate. This work will end, she promises, at the stroke of midnight on December 31, 2014, when her websites will be closed. “I will return to being a writer, but perhaps not to fiction,” she says. “I am not really interested in fiction.”

We agree to meet at 6:00 p.m. on a Saturday night for dinner at her apartment in Prenzlauer Berg, in the former East Berlin. Hoai will be cooking. The menu, discussed in several emails, will blend East and West in a medley of flavors. Even before the first bite, I am impressed by the logic and rigor of her planning.

I ride the S train to Bornholmer Strasse and exit onto the bridge where thousands of East Berliners gathered on November 9, 1989 to demand entry to the West. This was the first border crossing to fall on that momentous night. Soon the Wall would come tumbling down and then all of East Germany and then the Soviet Union, as forty years of Cold War came to an end. Today the last vestige of this war can be found only in the few states like Vietnam that are still propped up by Marxist-Leninist ideology.

I walk down a wide boulevard with a trolley running down the middle of it. The street is lined with modest five-story buildings, a few small cafes and billiard parlors, a bookshop, and some stores selling vegetables, beer, and coffee. I ring the bell and walk upstairs to the apartment that Hoai shares with her German partner. I am greeted at the door by a trim woman with a round face, pixie haircut, and lustrous smile. The first thing I notice on entering Hoai’s apartment is a blinking array of lights and switches—an industrial strength security system that Hoai installed after death threats and attacks on her computers.

Walking down a hallway, we pass a bathroom with a Japanese soaking tub and a modern kitchen to arrive at a large room that opens onto bedrooms and studies and yet more doors, hidden behind Japanese sliding screens. Hoai tells me that the unusual layout is due to the fact that she and her partner recently knocked down the walls and put together two separate apartments. The room holds a dining room table, decorated with a bouquet of freshly cut daisies, and a bookshelf filled floor-to-ceiling with a neatly archived collection. In Hoai’s office next door, more shelves are filled with clasp binders in serried ranks.

Seated at the table are Andreas, Hoai’s companion, and Dan, her son from her former marriage. A handsome man in a blue work shirt, Andreas runs a ten-person electrical engineering firm that specializes, among other things, in installing alarm systems. The apartment is his handiwork, and so, too, is the security system at the front door. With an ironic tug to his smile, he is the kind of solid fellow one would want to consult after receiving death threats.

Dan, nineteen, is a slender young man who will be studying applied computation and mathematics at Jacobs University in Bremen in the fall. He lives nearby with Hoai’s former husband, a German whom she married in 1991. Hoai speaks English quite well, but Dan is fluent, and he is being pressed into service tonight as his mother’s translator.

Hoai explains that the meal will be running from spicy to not-so-spicy, from hot to cold, “the opposite direction from normal,” she says. The thought enters my mind that the meal will be retracing her steps into exile, moving from the spicy East to the temperate West. While Hoai busies herself in the kitchen, I chat with Andreas about Prenzlauer Berg, the bohemian enclave that is rapidly being gentrified. “In this building we have Italians, Argentineans, Russians, Americans, and Vietnamese,” he says. “I am the only German.”

“The reason this part of the city still exists is because the East Germans had no money to destroy it,” he says. “The area is full of artists. The poor ones live in the basement. The rich ones live on top.” Bemused by Berlin’s new-found prosperity, Andreas for kicks spends his weekends cycling pedicabs full of tourists around the city.

The table is set with a full assortment of crystal glasses, a fish knife, and three forks for each upcoming course. We start drinking a Gewürztraminer Riesling and later switch to a Spanish Rioja. During our first course—papaya salad with shrimp, a Thai dish—I get a closer look at my hostess. Nam, as she is known to her friends (her full name is Pham Thi Hoai Nam) has the classic features, flat nose, golden skin, high cheekbones, of a north Vietnamese. Dressed in jeans, a white blouse, and a light wool sweater, also white, she wears wire-rim spectacles with tortoise shell highlights and a pair of silver earrings holding a dark stone, maybe an emerald. The conversation flows through English, German, French, and Vietnamese—whichever is the sharpest tool for the concept at hand.

“I am not sure of my exact birth date,” Hoai says, when I ask about her family. “It was sometime in 1960, during the war, when people didn’t register births until weeks or months after they occurred.”

“During Ho Chi Minh’s version of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in the 1950s, my parents were sent from Hanoi to the countryside, to work as school teachers,” she says. “My grandfather had been Minister of Education in Thanh Hoa province, but my father, revolting against his bourgeois background, had left at the age of twelve to fight with the Viet Minh. His big dream was to become a Party member, but he was never allowed to join.”

Her father’s uncle was Pham Quynh, a journalist and publisher of the largest Vietnamese newspaper in the French colony. Quynh was minister of education and then minister of the interior in the government of the last Vietnamese emperor, before he was kidnapped and killed by the communists in 1945.

“The first generation of communist leaders all came from bourgeois families,” she says. “But after the Party was formed, they closed the door behind them. No one else from the bourgeoisie could rise into the ranks. They needed followers, not leaders. They needed useful idiots.

“Ho Chi Minh is the perfect example. He eliminated all the intellectuals around him, thereby removing the competition. Since then, the idiots have reproduced themselves so successfully that in the present government not a single official speaks a foreign language, and this is in spite of the fact that eighty percent of them have Ph.D. in their title.”

Excelling in school, Hoai in 1977 was chosen as one of a hundred and thirty students sent to the Eastern Bloc to be trained as archivists by the Stasi and other communist police agencies. “This was paradise for us,” she says, about leaving war-torn Vietnam for Europe. The war had been present for the first fifteen years of her life “like clouds in the sky,” and then after the war came the “reign of hardline ideology,” a period of “poverty, backwardness, and repression.”

One day, one of her professors at Humboldt University saw her waiting at a bus stop reading a book. Another day, he cracked a joke in class about Robert Musil’s Man Without Qualities. “I was the only one who laughed, because I was the only one who had read the book,” she says.

“He sent me on an internship, first to the Goethe archives, then to the Schiller and Brecht archives, where I wrote my master’s thesis. These were happy days for me, spent reading and living among the papers of these great writers. My professor did me a big favor,” she says.

After six years in Germany Hoai moved back to Vietnam in 1983, where she worked as an archivist at the Institute of History and began, in her spare time, to write short stories and novels. “When I was twelve, I thought I was born to be a writer. Now, I think I may not have been correct. One is not born to be anything. One chooses what to do.”

“I went back to Vietnam because I was disappointed by life in East Germany,” she says. “It was just like Vietnam. There was no freedom or human rights, and the East German food was horrible.”

“I thought I had a debt to Vietnam, for having sent me here to be trained,” she says. “But on my return, I was classified as ‘untrustworthy,’ because of the time I had spent abroad.”

In 1988 Hoai published The Crystal Messenger, the novel that made her famous in Vietnam and pushed her to the forefront of doi moi writers. It also got her censored and eventually banished from the country. Vietnamese censors, with what Hoai describes as “a twinge of idiocy,” will block books from publication, if there is too much interest in them, or ban books that have already been published, if they become too successful. This is what happened with The Crystal Messenger. It was pulled from the shelves after selling fifty thousand copies and winning the LiBeraturpreis for the best foreign novel at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Told through the interweaving stories of several young women, one of them a Vietnamese Amerasian who comes of age in a country corrupted by careerism and consumerism, The Crystal Messenger is an allegory about the reunification of north and south Vietnam. It tells a wry tale about how a beautiful Vietnamese Amerasian with Texan blood can conquer the hearts of all the uptight men in Hanoi. In their banning order, the censors charged Hoai with “salacious” writing, an “excessively pessimistic view” of Vietnam, and of abusing the “sacred mission of a writer.”

Hoai went on to publish literary essays, two collections of short stories, Me Lo (1989) and Man Nuong (1995), and another novel, Marie Sen (1996). At the same time, she was producing numerous translations from German into Vietnamese. After publication of The Crystal Messenger, nothing written by Hoai has been published in Vietnam, except for a few things that appeared in print and were quickly suppressed. “The censors never tell you when a book is withdrawn from circulation. I consider myself lucky if I even learn that something has been published in the first place.”

“The same thing happened all the time in East Germany,” says Andreas. “Here we had lots of films that were made, and then the censors got scared and never released them.”

“One day I received in the mail an article that I had written,” says Hoai. “It had been heavily censored, and it even had someone else’s name on it. Everyone in Vietnam accepts this level of corruption. It doesn’t even surprise me anymore.”

Now Hoai posts all her writing online. “I’m not writing books for money,” she says. “I write to make myself happy.”

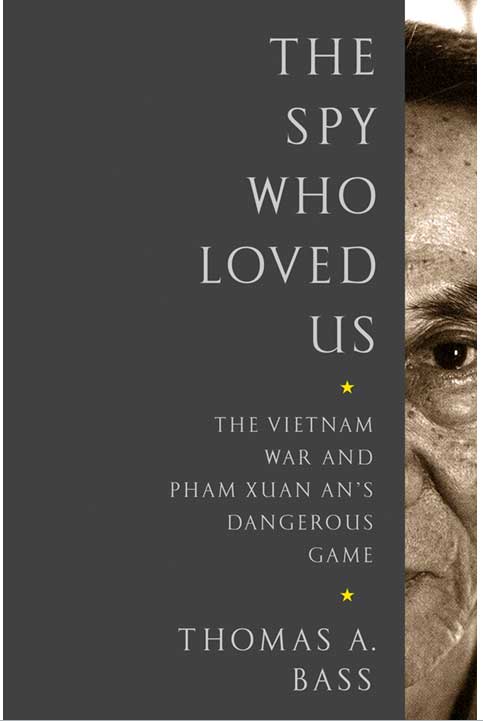

“Every author I deem important is publishing his or her works online, rather than allowing them to be censored. Some let their work be published in hard copy—censored—and then send it to Talawas to be published in its original form.” She suggests that I do the same thing with The Spy Who Loved Us, and I tell her that I will be pleased to accept her offer.

Moving on to a German recipe, our next course is celery-apple soup. Dan is working hard as his mother’s amanuensis, while Andreas sits listening, sometimes offering a humorous quip or story of his own.

In 1993 Hoai returned to Berlin, where she had lived as a student a decade earlier. The city had been transformed in her absence, with the Wall coming down and Westerners flooding into the ramshackle neighborhoods of the former East Berlin. Hoai settled in the city and married. “I made several trips back to Vietnam when Dan was small, but since 2004, I have been banned from traveling to Vietnam,” she says.

In 2001 she had begun publishing the censored news out of Vietnam on her Talawas web site. “Talawas is a Dadaist name,” she says. “It was created by putting ‘Ta la’ (we are) together with ‘was,’ as in ‘Was ist los?’ (‘What’s up?’), which gives you a double entendre meaning either, ‘What are we?’ or ‘We are something.’” Her “journal of culture” became a target for government hackers who tried for years to close the site with denial-of-service and other electronic attacks. Hoai kept outsmarting them behind ever-more-elaborate firewalls, and she is proud of the fact that Talawas was only briefly closed twice. Electronically, she was following in the footsteps of her great uncle Pham Quynh.

“It lasted nine years, as long as Vietnam’s war with the French,” she says about her decision to close the site. “It took an entire day to put it out. It was updated several times a day. No one was volunteering to do the work; so I decided to put an end to it.”

“Ten years ago I stopped writing fiction,” she says. “Now, in two years’ time, I plan to write fiction again.” In the meantime, she has begun publishing a blog called pro&contra. “I want to use the next two years, via the blog, to return to writing. I want to get an inventory of what I am able to do and my strengths. This is a transitional phase for me to learn to walk again.”

“When I get back to writing, I will be writing a combination of fiction and nonfiction,” she says. “Pure fiction is too boring. The Vietnamese reality is more interesting than any fiction I could imagine.”

While running her web sites, Hoai has supported herself as a simultaneous translator—rejecting only the most odious clients. “I watch the delegations of high Vietnamese officials,” she says. “They come to Germany to learn, but they learn nothing. They are people with no education. This is why they hire me. They don’t even know who I am.”

“She is seldom at home,” says Dan, of his mother’s busy schedule as an interpreter.

After a salad of radish sprouts, tomatoes, and carrots, our next course is a baked codfish served with rice. “While talking, I forgot to turn on the oven,” Hoai apologizes. “Cooking is like prose writing, not poetry. It takes the same attention to creative detail.”

We return to talking about censorship. “The governments of China and Vietnam are not afraid of anything,” she says. “This is linked to U.S. tolerance of their oppression. The U.S. does nothing to oppose them; so they have nothing to be afraid of.”

“Before their economies boomed, they weren’t sure of the Western response, but now they know,” she says. “If business is booming, then they have nothing to fear from the West. Whenever I criticize human rights in Vietnam, the government refers to the prisoners in Guantánamo. ‘If the Americans can do it, why can’t we? We aren’t doing anything different.’ Whenever I criticize corruption, they start talking about Lehman Brothers. Whenever I criticize the economy, they say, ‘Look at Spain or Greece.’ The pool of bad examples they draw from is just too large.”

“The government in Hanoi was lucky,” she says. “During the Cold War they had a lot of support from Western countries, especially from leftist movements. Now they have the support of the global capitalists. Standing in this good light, they don’t need to fear anybody. They have always found support in the West, whether during the Cold War or now.”

Andreas opens another bottle wine for our next course, a fruit and cheese tray, and Hoai excuses herself to go smoke a cigarette.

“When I first started writing, I had no money for cigarettes,” she says, on her return. “A friend said, ‘I will give you one cigarette per page.’ As time went on, to fill up the pages faster, my letters got bigger and bigger. I still write for cigarettes,” she says. “But now, I allow myself to smoke after every line.”

Hoai tells me a story about how censorship destroys even successful writers. “One day in Vietnam a writer came to me, asking for my advice. ‘How can I write about the war?’ he said. He had written books about the war, but they were not working anymore, and now he had no clue what to write.

“This is a story about a writer who has died as a writer, who has been eliminated. A serious writer would not consider what people wanted to read. He would look at his own perception of the war. This writer had been writing in a style approved by the government. He had voluntarily adopted this style, which made the work of the censors superfluous. It also made him susceptible to every new way of being censored, including censorship through the market, which allows you to write only what you’re expected to write, and which is happening more and more.”

She tells me the Vietnamese are borrowing their approach to censorship from the Chinese. “We always look to the Chinese and copy them, but when we copy them, we do it even worse than the Chinese, several orders of magnitude worse and in even more minute detail.”

“It is mandatory for every high Vietnamese official to get training in China once a year, just as it was in the time of the Cold War,” she says. “It is no accident that every campaign and law in China a half year later is introduced into Vietnam. Right now the press is filled with the Bo Xi Lai scandal—a high official accused of corruption. In Vietnam the sides are set for a similar struggle for power. I am certain that a Vietnamese official will soon be suffering the same fate.”

“Your story about the writer who came to visit you reminds me of Bao Ninh,” I say. “Without consulting anyone, he wrote the great novel about the war.”

“I don’t think it’s a great novel,” she says. “I am not fond of the Romantic style, and the way it’s written in Vietnamese is very Romantic. The English translation is different from the original, and perhaps this explains why the book is more popular for English readers than Vietnamese. The English translation was inevitably—because of the nature of English—more direct.”

“I prefer Franz Kafka to Thomas Mann,” she says. “I prefer a clear, crisp intelligent use of language, which dispenses with any decoration or superfluous elements.”

“This is the language she uses to boss me around,” says Dan. All of us, including his mother, laugh at the joke.

I ask about the two novels Bao Ninh wrote after The Sorrow of War. “He has retreated because of censorship, gone into internal exile,” she says. “Everybody who hasn’t migrated from Vietnam suffers from this.”

“The best thing for Bao Ninh would be live his life, after writing his one book,” she says. “At the end of his life he can publish his last, best work. Then he will have two books in his life, one at the beginning and one at the end. This is the best thing for a writer.”

She explains how it is getting rarer for artists to leave Vietnam for the West. “Artists and writers live better than ever before in Vietnam,” she says. “With today’s media, the people who can write, who can create things for radio, TV, and the internet are at a premium. Intellectuals and artists who have spent time abroad find that life is so expensive that they are not able to create anything. You can’t be creative and write under these circumstances, so you return.”

“I am no longer a Vietnamese citizen,” Hoai says. “I have a German passport. It is my trauma to be Vietnamese. My son has been spared this trauma. Why am I still confronted by Vietnamese problems? They stopped worrying about human rights and losing the support of the West when they realized that all the West cares about is making money.”

The major exception to the banalization of Vietnamese literature is Duong Thu Huong. She is a throwback to the days when exiled authors were politically potent. When I mention her name, I can tell from Andreas’s and Dan’s raised eyebrows that Huong has already been a subject of conversation. “I admire her courage and bravery,” Hoai says. “She can be very disagreeable, but that’s alright. She is very honest and frank.

“I am not fond of her work, though. Her writing is tendentious. When she claims something is bad she tries to prove it in her writing. When you read her books, you won’t find any surprises. You know what’s going to happen. You know in advance who are the good guys and the bad guys, and that’s pretty boring.

“The structure of her work is also boring, which is too bad, because she is a good observer of details, and her narrative skills are pretty good. When she’s not drifting into propaganda, her use of language can be very beautiful, as well. If she could get beyond propaganda and make use of her skills, she could be a fine writer.”

Pham Thi Hoai is the polar opposite of Duong Thu Huong. Her writing is concise and elegant. Her stories are deftly crafted. She is conducting an intellectual conversation, not with the ghosts of dead combatants, but with Kafka and the other writers whom she has translated into Vietnamese.

In other ways, though, Pham Thi Hoai is very much like Duong Thu Huong. Both decided to place the fight against Vietnam’s authoritarian government above their work as writers. Both are committed militants, fearless opponents of a regime they consider corrupt and oppressive. While Hoai runs the most important websites for Vietnamese dissidents, her writing is required reading for tens of thousands of Vietnamese, both inside and outside the country. She is one of the axes around which Vietnam’s artistic community turns, a commander leading the attack on Vietnam’s censors.

When I ask Hoai about Duong Thu Huong’s Novel Without a Name, she says, “I read only twenty pages and put it down.” So who is she reading today? Hoai mentions Mo Mieng, the Open Your Mouth poets, who have not been translated into English, since their writing is “difficult.” Mo Mieng began as a quartet of poets who set out in the early 2000s to shock the niceties of Vietnam’s Confucian norms. They use the language people speak on the street and publish their work in samizdat xeroxes passed from hand-to-hand. “We want to avoid the state censorship that often cuts the life out of literary works,” Open Your Mouth poet Ly Doi told the BBC in 2004. Since then a dozen other Vietnamese artists have begun writing “dirty” poetry, and Hoai recently released on her website the dirtiest of Vietnamese literary transgressions, a work called “Di Thui” (“Stinking Whore”) by Nguyen Vien, which retells Vietnam’s national epic, The Tale of Kieu, as an attack on the Communist Party.

I ask Hoai if she sees any signs of hope for things getting better in Vietnam.

She clears her throat for an oracular pronouncement, and Andreas laughs. “Twenty years from now the ocean will be much higher than it is today, so the coastal area won’t exist anymore,” she says. “If the coastal people are gone, the mountainous people will remain. If Vietnamese literature succeeds in moving from the coastal areas to the mountains, it will survive. It might also learn to swim.”

“The internet does not know the flooding of oceans, so the internet is a space where one can survive,” she says. “Maybe Vietnam will become the first cyberspace country—a country that exists only in cyberspace.”

By then Vietnam’s literature and culture, maybe all of Vietnam itself, will be updated daily and living online, and cyberspace will be the only space in Vietnam free of censorship.