23 Apr 2015 | Ireland, News, United Kingdom

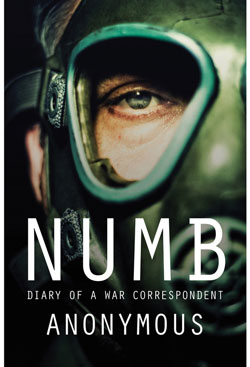

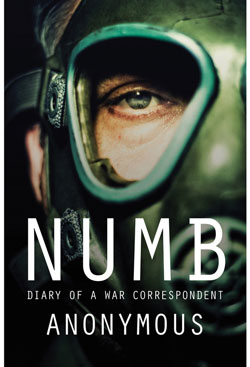

Who is Alan Buckby? According to Liberties Press, publishers of Numb: Diary of a War Correspondent, Buckby is the pseudonym of a 55-year old British foreign correspondent who was killed on assignment in 2014.

“A war correspondent for more than two decades, he led a double life, appearing to be a regular family man while at home in London, but immersed in sadism and depravity while on overseas assignments. He didn’t just document the violence – he became directly involved in it.”, the Liberties website blurb tells us excitedly.

Fun stuff, if you’re into that sort of thing. The ghostwriter, Louis La Roc, claimed that the materials for the book had come via a mutual friend from “Kay Buckby”, the wife of the deceased reporter.

Earlier this month, “Louis La Roc” appeared on two national radio stations in Ireland, luridly describing the contents of the book, to much criticism from Irish journalists. RTE’s Fergal Keane (not to be confused with the BBC’s Fergal Keane) dismissed the La Roc interview on the station’s John Murray show as “the biggest load of crap I have ever heard”, while the Irish Times’s Hugh Linehan called the interview (and by extension the book) “torture porn”.

Linehan invited Louis La Roc on the Irish Times’s Off Topic podcast on 18 April, where he and fellow Irish Times writer Patrick Freyne questioned him on the veracity of the details in the book. The timeline was, to put it mildly, all over the place. To give one example, in the book it is claimed that Buckby went to Northern Ireland in the early 80s because he was fascinated by British broadcasters’ ban on the broadcast of the voices of Sinn Fein and IRA spokespeople. In fact, that ban was only introduced in 1988. The author claimed that the various discrepancies in detail were introduced to protect the innocent, and that he had used a “cinematic jumpcut” technique to help the narrative along. Moreover, no one could find any evidence of a 55 year-old British foreign correspondent who died in late 2014.

The journalists questioned how long it had taken La Roc to write the book, from receiving the raw material to delivering to the publishers. Three months, apparently. When Freyne expressed surprise at this, La Roc suggested that it was about the same length of time as it took Siobhan Curham to work up Girl Online, the novel published under the name of vlogger Zoella that was one of last year’s best selling books, as if they were identical projects.

After the podcast, in which La Roc was openly accused of peddling fiction as fact, Freyne kept digging, and discovered that La Roc was more than likely the pen name of Colin Carroll, a self-promoter who had in the past, among other things, set up something called The Paddy Games and a website called Irish Empire. At one point he even had a joint BBC/RTE TV show, Colin And Graham’s Excellent Adventures (in the blurb for which, Colin and Graham are described as “sporting hoaxers”).

The coup de grace was delivered when another writer, Donal O’Keeffe, dug up a 2010 interview with Colin Carroll in a local newspaper, the Avondhu Press, in which he had said he was working on a novel with a war journalist as protagonist.

All in all, a very satisfactory bit of sleuthing for all concerned.

What happened next was interesting. Because what happened next was absolutely nothing. Numb is still out there, still listed under the non-fiction section of the Liberties Press website. The blurb still makes the same claims as it always has about the genesis of the book. The publisher is standing by the book, despite confirming that he made no attempt to verify the inflammatory information contained within. Perhaps defiantly, a quote from Oscar Wilde hovers at the top of the page: “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.”

It is as if…it is as if this is the kind of story that only journalists really care about (and you, dear reader, considering you’ve made it nearly 700 words into this piece. But you’re probably a hack too, aren’t you?).

And that is something that should give journalists pause for thought. Do people see us as we see ourselves? And do people put the same value on accuracy and truthfulness as we claim to?

Think of the great journalistic scandals of the past few years: when the story broke of Johann Hari’s fabrications and sockpupetting back in the summer of 2011, journalists talked about little else among themselves. Really, seriously, nothing else for about a month. But were Hari’s Independent readers camped outside Northcliffe House, furiously demanding apologies and clarifications from the paper and Hari himself? No. Non journalists I spoke to about the issue didn’t really understand what the fuss was about.

Or think of Jonah Lehrer, who made up quotes. Sure, like Hari, he was eventually dropped by employers, but did his readers really care that he’d put words in Bob Dylan’s mouth?

Meanwhile, online activists (not naming any names) spread all sorts of nonsense that gets more shares than many social media managers could dream of, because it contains that magical element of “truthiness”, to borrow a phrase from Stephen Colbert: it tells people what they want to hear. Just last week, lots of left wingers got terribly excited about a headline for a column in the Times which said that the Conservatives had got the economy wrong. “Wow ! The Times newspaper nails the Tory Lib Dem lie about the deficit & the financial crisis.” tweeted Michael H, with an accompanying picture of the headline “It’s a lie to say the Tories rescued the economy”. The tweet spread like wildfire, with the subcurrent being that EVEN THE MURDOCH PRESS was backing Labour now. The fact that the headline accompanied a guest column by a Labour peer seemed not to matter. The people sharing wanted it to be an attack on the Conservatives by the Murdoch press, and so it was.

It was the same desire for truthiness that fed the likes of Hari, and to an extent, feeds the publishers of Numb. It was what led Piers Morgan to publish photographs allegedly showing British soldiers torturing Iraqis, even though they were obviously false.

And I suspect it was behind Liberties Press decision to publish the “torture porn” of Numb: it felt like the kind of thing that might just be real.

It is important that journalism realises its duty to entertain and not just hector (not all journalism is, or should be, the “investigative journalism” so lionised by Royal Charter-waving groupies as the true untainted thing). But journalism should at least, be against truthiness, if only out of self interest. If anyone can make stuff up and get 1,000 shares on Twitter, why pay people for deep digging or elegant writing?

But consumers of media have a role to play in this too: everyone should be actively alert to the difference between stuff that is true and stuff that merely feels right, and not encourage the latter. As George Orwell wrote: “We shall have a serious and truthful and popular press when public opinion actively demands it.”

This column was posted on April 23 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jan 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

[vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495018452261{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column css=”.vc_custom_1474781640064{margin: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477669802842{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;}”]CONTRIBUTORS[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495018460243{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781919494{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Karim Miské” title=”Novelist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89017″]Karim Miské is a documentary maker and novelist who lives in Paris. His debut novel is Arab Jazz, which won Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 2015, a prestigious award for crime fiction in French, and the Prix du Goéland Masqué. He previously directed a three-part historical series for Al-Jazeera entitled Muslims of France. He tweets @karimmiske[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781952845{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Roger Law” title=”Caricaturist ” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89217″]Roger Law is a caricaturist from the UK, who is most famous for creating the hit TV show Spitting Image, which ran from 1984 until 1996. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Observer, The Sunday Times and Der Spiegel. Photo credit: Steve Pyke[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781958364{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Canan Coşkun” title=”Journalist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89018″]Canan Coşkun is a legal reporter at Cumhuriyet, one of the main national newspapers in Turkey, which has been repeatedly raided by police and attacked by opponents. She currently faces more than 23 years in prison, charged with defaming Turkishness, the Republic of Turkey and the state’s bodies and institutions in her articles.[/staff][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” css=”.vc_custom_1474815243644{margin-top: 30px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 30px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1474619182234{background-color: #455560 !important;}”][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white”]Editorial

“We had tongues, but could not speak. We had feet but could not walk. Now that we have land, we have the strength to speak and walk,” said a group of women quoted in Ritu Menon’s article discussing why ownership of land has started to shift the power balance in India.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720631074{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495018553351{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/winter2014-magazine-cover-e1434042891830.jpg?id=62269) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495018522192{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Contents

A look at what’s inside the winter 2014 issue[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720637924{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495018679207{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Gaiman-pic-credit-Kimberly-Butler.jpg?id=62304) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495019209534{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Podcast

Neil Gaiman and Martin Rowson on censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1491994247427{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493814833226{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495018869817{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/15721410208_a036ffe467_o.jpg?id=62585) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495018840047{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Information war

Andrei Aliaksandrau investigates the new information war as he travels across Ukraine.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815095611{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495019050825{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/magna-carta.jpg?id=62653) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495019017760{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]1215 and all that

John Crace on the Magna Carta: Don’t shit with the people, or the people shit with you. Or something like that.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815155369{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495019157426{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/20160127-_MG_4305.jpg?id=72965) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495019127591{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Thoughts policed

Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including Drafting freedom to last.

Subscribe now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Dec 2014 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Packed inside this issue, are; an interview with fantasy writer Neil Gaiman; new cartoons from South America drawn especially for this magazine by Bonil and Rayma; new poetry from Australia; and the first ever English translation of Hanoch Levin’s Diary of a Censor; plus articles from Turkey, South Africa, South Korea, Russia and Ukraine.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, authors from around the world including The Observer’s Robert McCrum, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak, and Nobel nominee Rita El Khayat consider which clauses they would draft into a 21st century version of the Magna Carta. This collaboration kicks off a special report Drafting Freedom To Last: The Magna Carta’s Past and Present Influences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”62427″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Also inside: from Mexico a review of its constitution and its flawed justice system and Turkish novelist Kaya Genç looks at recent intimidation of women writers in Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: DRAFTING FREEDOM TO LAST” css=”.vc_custom_1483550985652{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The Magna Carta’s past and present influences

1215 and all that – John Crace writes a digested Magna Carta

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson imagines a shock twist for King John

Battle royal – Mark Fenn on Thailand’s harsh crackdown on critics of the monarchy

Land and freedom? – Ritu Menon writes about Indian women gaining power through property

Give me liberty – Peter Kellner on democracy’s debt to the Magna Carta

Constitutionally challenged – Duncan Tucker reports on Mexico’s struggle with state power

Courting disapproval – Shahira Amin on Egypt’s declining justice as the anniversary of the military takeover approaches

Digging into the power system – Sue Branford reports on the growth of indigenous movements in Ecuador and Bolivia

Critical role – Natasha Joseph on how South African justice deals with witchcraft claims

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Brave new war – Andrei Aliaksandrau reports on the information war between Russia and Ukraine

Propaganda war obscures Russian soldiers’ deaths – Helen Womack writes about reports of secret burials

Azeri attack – Rebecca Vincent reports on how writers and artists face prison in Azerbaijan

The political is personal – Arzu Geybullayeva, Azerbaijani journalist, speaks out on the pressures

Really good omens – Martin Rowson interviews fantasy writer Neil Gaiman, listen to our podcast

Police (in)action – Simon Callow argues that authorities should protect staging of controversial plays

Drawing fire – Rayma and Bonil, South American cartoonists’ battle with censorship

Thoughts policed – Max Wind-Cowie writes about a climate where politicians fear to speak their mind

Media under siege or a freer press? – Vicky Baker interviews Argentina’s media defender

Turkey’s “treacherous” women journalists – Kaya Genç writes about dangerous times for female reporters, watch a short video interview

Dark arts – Nargis Tashpulatova talks to three Uzbek artists who speak out on state constraints

Talk is cheap – Steven Borowiec on state control of South Korea’s instant messaging app

Fear of faith – Jemimah Steinfeld looks at a year of persecution for China’s Christians

Time travel to web of the past and future – Mike Godwin’s internet predictions revisited, two decades on

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Language lessons – Chen Xiwo writes about how Chinese authors worldwide must not ignore readers at home

Spirit unleashed – Diane Fahey, poetry inspired by an asylum seeker’s tragedy

Diary unlocked – Hanoch Levin’s short story is translated into English for the first time

Oz on trial – John Kinsella, poems on Australia’s “new era of censorship”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Jodie Ginsberg writes about the power of noise in the fight against censorship

Index around the world – Aimée Hamilton gives an update on Index on Censorship’s work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Humour on record – Vicky Baker on why parody videos need to be protected

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Jul 2014 | Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, News

A local newspaper in the western German city of Darmstadt is at the centre of a legal case that will measure whether readers’ comments are protected by Germany’s press freedom laws.

On June 24, police and the Darmstadt public prosecutor arrived with a search warrant at the offices of the newspaper Echo. A complaint had been filed over a 2013 reader comment on Echo’s website. Months later, a local court issued a search warrant to force the newspaper to hand over the commenter’s user data.

The comment, which was left under the username “Tinker” on an article about construction work in a town near Darmstadt, questioned the intelligence of two public officials there. Within hours, Echo had removed the comment from its website after finding that it did not comply with its policy for reader comments. According to a statement Echo released after the June confrontation with police, the two town administrators named in the comment had filed the complaint, alleging that it was insulting. This January, Darmstadt police sent the newspaper a written request for the commenter’s user data. Echo declined.

When police showed up at Echo’s offices five months after their initial request for the commenter’s identity, the newspaper’s publisher gave them the user data, preventing a search of Echo’s offices. A representative for the Darmstadt public prosecutor later defended the warrant.

“It’s our opinion that the comment does not fall under press freedom because we assume that the editorial staff doesn’t edit the comments,” Noah Krüger, a representative for the Darmstadt public prosecutor, told Echo.

According to Hannes Fischer, a spokesperson for Echo, the newspaper is preparing legal action against the search warrant.

“We see this as a clear intervention in press freedom,” Fischer said. “Comments are part of editorial content because we use them for reporting – to see what people are saying. So we see every comment on our website as clearly part of our editorial content, and they therefore are to be protected as sources.”

In early 2013, a search warrant was used against the southern German newspaper Die Augsburger Allgemeine to retrieve user data for a commenter on the newspaper’s website. In that case, a local public official had also filed a complaint over a comment he found insulting. The newspaper appealed the case and an Augsburg court ruled that the search warrant was illegal. The court rejected the official’s complaint that the comment was insulting, but also ruled against Die Augsburger Allgemeine’s claim that user comments are protected under press freedom laws.

In Echo’s case, the commenter’s freedom of speech will likely be considered in determining whether the comment was insulting. If convicted of insult, the commenter could face a fine or prison sentence of up to one year. Given the precedent from the 2013 case and the public prosecutor’s response, it’s unclear whether press freedom laws may be considered against the search warrant. Ulrich Janßen, president of the German Journalists’ Union (dju), agreed that user comments should be protected by press freedom laws. “If the editors removed the comment, then that’s a form of editing. That speaks against the argument that comments are not editorial content,” Janßen said. Warning that the search warrant against Echo may lead to intimidation of media, Janßen cautioned, “Self-censorship could result when state authorities don’t respect press freedom of editorial content.”

Recent reports from Germany via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Court rules 2011 confiscation of podcasters’ equipment was illegal

New publisher of tabloid to lay off three quarters of employees

Police use search warrant against newspaper to obtain website commenter’s data

Blogger covering court case faced with interim injunction

Competing local newspapers share content, threatening press diversity

Transparency platform wins court case against Ministry of the Interior

This article was posted on July 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org