3 Sep 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements, Turkey, United Kingdom

British journalist Jake Hanrahan and cameraman Philip Pendlebury were arrested last Thursday, 27 August, whilst reporting from south-eastern Turkey along with two Vice News colleagues. One colleague was later released but Hanrahan, Pendlebury and their colleague Mohammed Ismael Rasool were subsequently charged with ‘working on behalf of a terrorist organisation’. They were reportedly moved to a high security prison on Wednesday 2 September, before being released earlier today, 3 September.

While we warmly welcome the news that Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury have been released we nevertheless remain seriously concerned for Mohammed Ismael Rasool. Reports suggest that Rasool is still in detention, and we join Vice News in continuing to call on the Turkish authorities to release him immediately and unconditionally.

Following their arrest last Thursday, 27 August, Index on Censorship, English PEN and PEN International wrote to the EU, the Council of Europe, of which Turkey and the UK are members, and to the UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond to raise the case. Today’s release comes a day after the Foreign Office issued a statement echoing the groups’ concerns and reminding Turkey of their international obligations.

We also remain extremely concerned about the current crackdown on freedom of expression in Turkey. We recognise that Turkey is facing a period of heightened tension. However at such a time it is more important than ever that both domestic and international journalists are allowed to do their vital work without intimidation, reporting on matters of global interest and concern.

TAKE ACTION

Send a message of support

Tweet your support for Mohammed Ismael Rasool with the handle @vicenews and hashtags #FreeViceNewsStaff #FreeRasool

Write to the authorities

Calling on the Turkish authorities to release Mohammed Ismael Rasool immediately; Urging the authorities to allow journalists to fulfil their essential role of reporting events that are in the public interest and of international concern at a time of tension in Turkey and throughout the region; Reminding the authorities that Turkey has the obligation to respect the right to freedom of expression under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which it is a state party.

Appeals to:

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Cumhurbaşkanlığı Sarayı

06560, Beştepe

Ankara, Turkey

Fax: +90 312 525 58 31

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @RT_Erdogan

Minister of Justice Bekir Bozdağ

Milli Müdafaa Caddesi No: 22

Bakanlıklar

06659, Kızılay

Ankara, Turkey

Fax: +90 312 419 33 70

Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Twitter: @bybekirbozdag

His Excellency Mr. Abdurrahman Bilgic

Turkish Embassy

43 Belgrave Square

London

SW1X 8PA

United Kingdom

Fax: +44 20 73 93 00 66, +44 20 73 93 92 13

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @TurkEmbLondon

2 Sep 2015 | About Index, Counter Terrorism, Egypt, mobile, News, Turkey, United Kingdom

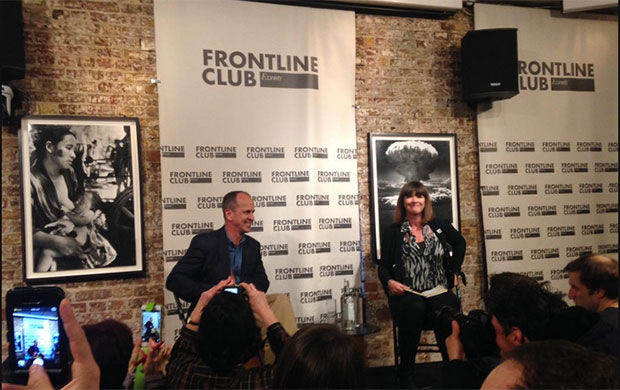

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

The arrest by Turkey of journalists for Vice News, just two days after the sentencing of Al Jazeera reporters in Egypt, demonstrates how easily terror laws can be abused to stifle a free and independent media.

It should be a wake-up call for the UK, which in the next few months will introduce yet another piece of anti-terrorism and extremism legislation that could be used in much the same way.

On Monday, two British reporters and a translator working for international news organisation Vice News were charged by a Turkish court for “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”, after filming clashes between government forces and Kurdish militants. The charges came just days after the sentencing in Egypt of three Al Jazeera journalists – accused of aiding the banned Muslim Brotherhood – for “spreading false news”.

The injustice in both cases is patent. In both cases laws meant to tackle terrorism and extremism are being used against journalists simply trying to do their job: to report the news.

Tobias Ellwood, the UK Minister for the Middle East and North Africa, said he was, “deeply concerned by the sentences handed down” against the journalists in Egypt. But what should also be concerning us is how easily that could happen in the UK as the government seeks ever broader powers, and definitions of terrorism that uses language little different to that being used to charge journalists like those of Vice News and Al Jazeera.

The UK government already defines extremism very broadly, as “the vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs” – a net wide enough to catch Islamic fundamentalists, neo-Nazis, but also potentially anyone who preaches, for example, against gay marriage. But the government is not content. Now it says it needs new laws to tackle those who “spread hate but who do not break existing laws”. And that is a net wide enough to catch, well, pretty much anyone who says anything with which the current government – or mainstream popular opinion – disagrees.

Conservative MP Mark Spencer argued last month that proposed new banning orders intended to clamp down on hate preachers and terrorist propagandists should be used against Christian teachers who teach children that “gay marriage is wrong”. And if that could be the case, it takes little imagination to see that “spreading hate” could easily be applied to those journalists who report on those groups and individuals who have hateful messages.

The government will argue that this is not how the law is intended. But you only have to look at communications intercept laws to see how easily “intentions” can be subverted and abused in practice. Police officers used powers afforded by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) – an act intended to deal with terrorists – to pull the phone records of Sun political editor Tom Newton Dunn so it could track down the officers accused of leaking information to the Sun over “Plebgate” – an incident with no terrorist implications whatsoever in which a minister was accused at swearing at the police.

The new extremism bill will be no different. It will give the government powers to ban a host of groups from speaking or publishing, powers that can easily be used to silence those not just with whom the government disagrees, but those on whom we rely to convey information – even when that information, as is so often the case with those brave enough to report on the most violent extremism, is deeply unpalatable.

Britain has rightly described itself as shocked by the Al Jazeera verdict in Egypt. I hope it will be vocal in its condemnation of the arrest of VICE News’ journalists in Turkey. And I hope it will then reconsider its plans to introduce new terror laws that will stifle free expression and a free media.

This article was originally posted at Open Democracy on 1 September 2015

1 Sep 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases, Turkey, United Kingdom

Wednesday 2 September:

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office issued the following statement:

“We are concerned at the arrest of two British journalists in Diyarbakir on 31 August, who have been charged with assisting a terrorist organisation. The journalists have been given access to a lawyer and were in direct contact with consular officials within 24 hours of their detention.

“Respect for freedom of expression and the right of media to operate without restriction are fundamental in any democratic society. Turkey is a state party to the European Convention on Human Rights and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. We would expect the Turkish authorities to uphold the obligations enshrined in those agreements.”

Tuesday 1 September:

Freedom of expression charities have written to UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond urging the UK to speak out publicly in defence of freedom of expression following the arrest of two British journalists and an Iraqi translator in Turkey under terror legislation.

The journalists and their fixer were were formally charged by a Turkish court on Monday with ‘aiding a terrorist organisation’. Vice News has described the charges as completely baseless.

The letter from PEN International, English PEN and Index on Censorship highlights the deteriorating situation for media in Turkey and urges Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond to speak out publicly against the arrests.

“Coming shortly after the equally unjust sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, we would note also the worrying increase in the use of terror laws to stifle a free and independent media globally and hope the UK will use its international position to help reverse this disturbing trend,” the groups say in the letter.

The groups have also written to the Council of Europe, of which Turkey and the UK are members, to express their concerns.

A copy of the letter can be found below.

Dear Mr Hammond,

We are writing to you on behalf of Index on Censorship, English PEN and PEN International, charities that campaign for freedom of expression in the UK and globally, to urge the immediate intervention of the British government in the case of three VICE News journalists, including two Britons, who have been charged with terror offences by the Turkish government.

The two British reporters, VICE News journalists Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury, along with their fixer, Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool, were formally charged by a Turkish court on Monday with ‘aiding a terrorist organisation’. We believe these charges to be baseless.

The three were detained by police with a fourth member of their team as they filmed in the south-east region of Diyarbakir on Thursday. Police interrogated them about alleged links to Islamic State and Kurdish militants.

You will be aware that the Turkish government’s routine use of counter-terrorism charges against journalists is a longstanding cause of concern for international human rights organisations and for the media in Turkey. There are rising fears that Turkey is on the brink of a new media crackdown in the run up to the parliamentary elections: Turkish police conducted a raid on the offices of Koza Koza Ipek Media group today, while an Ankara court has ruled in favour of a general search warrant for the Çankaya district of the Turkish capital (where embassies and foreign missions are based) allowing police to make preventative security searches and detentions for 30 days.

We recognise that Turkey is facing a period of heightened tension in the region. However at such a time it is more important than ever that both domestic and international journalists are allowed to do their vital work without intimidation, reporting on matters of global interest and concern.

A member of the Council of Europe, Turkey is a state party to both the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is therefore obliged to respect the right to freedom of expression and ensure that journalists are free to gather information without hindrance or threat.

We appreciate the Foreign Office’s consular assistance to the VICE News team and urge you to make a public statement in defence of freedom of expression in Turkey.

Coming shortly after the equally unjust sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, we would note also the worrying increase in the use of terror laws to stifle a free and independent media globally and hope the UK will use its international position to help reverse this disturbing trend.

Yours sincerely,

Jodie Ginsberg

Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

Maureen Freely

President, English PEN

Carles Torner

Executive Director, PEN International

1 Sep 2015 | mobile, News, Turkey, United Kingdom

The anti-terror charges against reporters for Vice News in Turkey are not isolated. In recent years, a number of countries have used broad anti-terror laws to restrict the freedom of the press.

Turkey

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

Two British journalists and a local fixer working for Vice News were charged on Monday 31 August in Turkey with “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”. They will remain in detention until their trial, the date of which has not yet been announced.

The journalists Jake Hanrahan, Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between security forces and youth members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir on Thursday when they were arrested.

Turkey’s broad definition of terrorism means that any journalist reporting on PKK activities or Kurdish rights can be charged with the offence of making “terrorist propaganda” and jailed.

Index on Censorship Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg said: “Coming just days after the unjust sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, these latest detentions of journalists simply for doing their jobs underlines the way in which governments everywhere can use terror legislation to prevent the media from operating.”

Egypt

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Egypt remains a cause for concern when it comes to press freedom: on 29 August 2015 Al Jazeera journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were sentenced to three years in prison. The journalists were found guilty of of “broadcasting false information” and “aiding a terrorist organisation” – a reference to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The sentencing came just weeks after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government passed an anti-terror law setting a fine of up to 500,000 Egyptian pounds (£41,600) for journalists who stray from government statements or spread “false” reports on attacks or security operations against armed fighters.

Jordan

Jordan introduced a new “anti-terror” law in 2006 prohibiting, among other things, the engagement in “acts that expose the kingdom to risk of hostile acts, disturb its relations with a foreign state, or expose Jordanians to acts of retaliation against them or their money”. The charge carries a prison sentence of three to 20 years. The law was amended in 2014 to , broaden the definition of terrorism.

Interpretation of the law has been varied. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in April 2015 a journalist was jailed for criticising the Saudi-led bombing of Houthi forces in Yemen. Another journalist was detained in July 2015 for breaking a recent ban on coverage of a terror plot. Earlier in 2015, an activist who criticised the royal family’s support of Charlie Hebdo on Facebook was sentenced to five months in jail under the anti-terror law.

Tunisia

One month after June’s terrorist attack on Sousse beach killing 38 tourists, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, Tunisia approved new anti-terror legislation.

Under the legislation, website editor Nour Edine Mbarki was charged in connection with publishing a photograph of a car that purportedly transported a gunman behind the beach attack. According to the CPJ, he was charged under Article 18 of the law with “complicity in a terrorist attack and facilitating the escape of terrorists,” which carries a prison term of between five and 12 years. He is currently awaiting a trial date.

Human Rights Watch said the new anti-terror bill “would open the way to prosecuting political dissent as terrorism, give judges overly broad powers, and curtail lawyers’ ability to provide an effective defence”.

Pakistan

Rights groups have long criticised Pakistan’s notorious anti-blasphemy laws for their effect on freedom of expression in the country. But strengthened anti terror legislation is also impacting the way journalists operate in the country.

In June, three Pakistani journalists were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act, reportedly for covering the activities of a dissident politician, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation. A year before, a TV anchor was also charged under the law.

One to watch: Kenya

Following two separate attacks by al-Shabab militants in December, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law a new security bill that could curtail press freedom. Under the new law, journalists could face up to three years in jail if their reports “undermine investigations or security operations relating to terrorism” – or even if they published images of “terror victims” without police permission.

This hasn’t come into play yet – in February, the Kenyan High Court threw out several clauses, including those that could impact media freedom. The government has said it would consider lodging an appeal.

This post was written by Emily Wight for Index on Censorship

This article was posted on 1 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org