14 Nov 2023 | Belarus, Lukashenko letters, News

It is important the international community pays close attention to the scale of politically motivated persecutions in Belarus, a panel discussion organised by the media organisation Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty recently said.

It was after Zmitser Dashkevich, a well-known Belarusian activist originally charged with extremism, had his sentence extended by a year after being charged with “blatantly disobeying penitentiary guards“. His sentenced was due to end in July. Journalist Andrei Aliaksandrau, a former employee of Index, recently spent his 1000th night behind bars after being imprisoned for 14 years in October 2022 for “extremist activities” against the state.

Anastasiia Kruope, assistant researcher for the Europe and Central Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, said there has been a large increase in human rights abuses and politically motivated persecutions in Belarus following Aleksandr Lukashenka’s heavily contested presidential election win in 2020.

“An atmosphere of fear and intimidation for journalists and human rights defenders was created,” she added.

“The way these people are treated in prisons and labelled extremist, along with the silencing of family members outside, means some of these cases may amount to crimes against humanity according to the UN.”

Aleh Hruzdzilovich was one such prisoner. A journalist for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, he spent nine months in prison and was released in September 2022. After covering the protests following Lukaskenka’s re-election for his job, he was arrested and charged with actively taking part in them.

“From the very first day, people like me recorded as extremists are punished more and have a stigma in prison,” Hruzdzilovich explained.

“It means we’re put in punishment cells and solitary confinement more often. When I was tortured, I was told to sleep on the wooden floor. If I simply sat down or stopped walking around the cell in the daytime, I was reported and given more time in the punishment cell.”

Hruzdzilovich described seeing a prisoner wet himself through fear of being sent to a punishment cell.

Pavel Sapelko is a lawyer based at the Viasna Human Rights Centre in Minsk, Belarus. He said there is an absolute power of prison authorities over prisoners in Belarus, which is affecting their human rights, and seemingly makes people “disappear”.

“The prisoners are simply incommunicado. The authorities can shut down visits and calls from families, and even then can only get help from a lawyer after their sentences are passed by law.”

Speaking of the legal system in Belarus, Sapelko described the debilitating change that has occurred over the past three years.

“We’ve lost more than 300 defence lawyers, with 100 of them being disbarred. Licences have been revoked, and six defence lawyers are actually behind bars, now prison inmates themselves,” he explained.

“This massively affects a lawyer willing to take on your case, especially for those charged with being extremists.”

Ending with another reason why the international community should support those journalists and human rights defenders still in Belarus with things such as legal help and visas, Kruope had one eye on the future.

“They have the connections to document these abuses. The powerful tool we have is accountability, and it may take many years for abusers to face justice. We can focus on preserving the evidence against these abuses and document them for the future.”

Please read about Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners here, which is a collaborative project by Index on Censorship in partnership with Belarus Free Theatre, Human Rights House Foundation and Politzek.me.

9 Oct 2023 | Belarus, News

On 9 October 2023, former Index colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau will have spent 1,000 days behind bars - imprisoned by Lukashenka’s regime for protecting free expression.

Journalist, media manager, and former employee at Index on Censorship, Andrei and his partner, Irina Zlobina were detained by officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs on 12 January 2021 and were accused of financing the protests in Minsk by paying fines and reimbursing the costs for detention for those detained during the protests.

After being held in pre-trial detention for nearly two years, in October 2022, the Minsk Regional Court sentenced Andrei to 14 years' imprisonment and a fine of 32,000 rubles ($12,600), and Irina to nine years in prison. On 20 January 2023 it was confirmed that both of them were included on the list of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign citizens or stateless persons involved in extremist activities, which, as of 31 May 2023 included 2,868 people, many of whom are political prisoners.

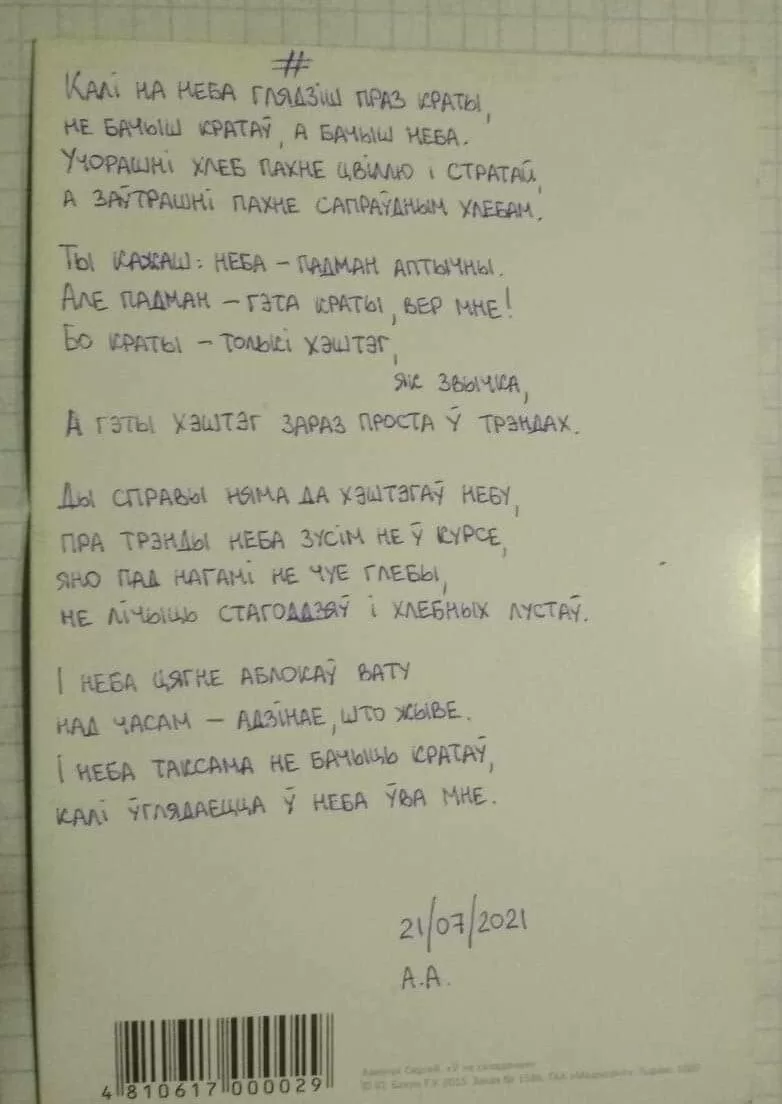

On 21 July 2021, three weeks after high treason was added to his charges, Andrei wrote a poem while in pre-trial detention. To stand alongside Andrei and to ensure his words can reach as many people as possible, some of his friends and former colleagues have come together to read his work in the two videos above.

By reading his work we are sending a message to Lukashenka’s regime: You may imprison those who stand up for democracy in Belarus but you can never silence them.

Translated from the original Belarusian by Hanna Komar and John Farndon

When you look out through the bars at the sky,

It’s not bars you see but the sky overhead.

Yesterday’s bread smells of mould and loss,

but tomorrow’s smells like genuine bread.

You say: the sky is a trick of the light.

But the bars are the trick of the light, I say!

Because bars are a hashtag,

just a habit, right?

And this is the hashtag trending today.

Yet the sky cares nothing for hashtags at all,

the sky has no thought for trends up ahead,

it does not feel the ground where our feet fall,

nor count the centuries and slices of bread.

The sky just draws clouds of cotton wool

over time — this is all that goes on really.

And the sky does not see any bars at all

when it peers deep into the sky in me.

In the original Belarusian

Калі на неба глядзіш праз краты,

не бачыш кратаў, а бачыш неба.

Учорашні хлеб пахне цвіллю і стратай,

а заўтрашні пахне сапраўдным хлебам.

Ты кажаш: неба — падман аптычны.

Але падман —гэта краты, вер мне!

Бо краты — толькі хэштэг,

як звычка,

А гэты хэштэг зараз проста ў трэндах.

Ды справы няма да хэштэгаў небу,

пра трэнды неба зусім не ў курсе,

яно пад нагамі не чуе глебы,

не лічыць стагоддзяў і хлебных лустаў.

І неба цягне аблокаў вату

над часам — адзінае, што жыве.

І неба таксама не бачыць кратаў,

калі ўглядаецца ў неба ўва мне.

7 Jul 2023 | Belarus, News

It is hard to imagine something more damning as an indicator of press freedom than a leader banning the country’s journalism union and threatening penalties and jail for anyone who has dealings with it.

Yet this is what has been done by Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s Belarus, fast becoming a model for media repression. In February, the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) was designated by the authorities in the country as an “extremist formation”.

The authorities also identified eight people, including BAJ chair Andrey Bastunets, who now face up to ten years in prison for "establishing or participating” in the organisation. Others who have financed or “abetted” BAJ could also face jail time, arbitrary detentions, interrogations, and searches.

While another 20 media companies, most of the mainstream, independent Belarusian media, have also been given a similar label, this is the first human rights organisation to be designated thus.

Now the Belarusian authorities have gone a step further and BAJ’s website, social media accounts and logo have now been designated as “extremist materials”. Anyone disseminating the association’s content or merely liking an article on its social feeds could mean a 15 day stay in jail.

The situation is like Britain’s government putting the National Union of Journalists in the same category as Al Qaeda.

Journalists in Belarus, at least those who report critically about Lukashenka’s activities, are now under threat. Some are in jail - 34 media workers at the end of June) – despite Lukashenka this week telling the BBC’s Steve Rosenberg that there are no political prisoners in the country.

Other journalists have left the profession while others have fled abroad.

In spite of these attacks, Bastunets, speaking to Index about the challenges facing journalists, says the independent media of Belarus is far from dead.

“Those journalists who left the country face different challenges than their colleagues in Belarus,” he says, with particular problems in obtaining legal residency in host countries, the high cost of living and renting accommodation even though many of them have their own, now empty, apartments in Belarus.

“There is also the different legal environment, language problems, the sometimes discriminatory attitude to Belarusians as co-aggressors, …and, for some, psychological burn-out.”

Many of those who left Belarus expected to return in a month or two, he says.

“Repression has been going on for almost three years and it is not clear when it might stop. And if media outlets have mostly coped with relocation, survival, and the arrangement of their activities, new challenges await us if current trends persist. One of them is the necessity of accepting the fact that we are in exile for a long time.”

But rumours about the death of the independent media in Belarus are “exaggerated”, he says.

“Several influential media outlets are still working in the country. But, of course, their working conditions are extremely unfavourable. Journalists live under constant threat of raids, detentions, interrogations, and criminal prosecution.”

As a result, media organisations that still operate in Belarus have reinforced safety measures for their journalists as well as using even more secure communications protocols.

They are also self-censoring to some extent.

“Editorial boards have to take extra care when publishing pierces on sensitive issues - on government activities, on opposition, on the war in Ukraine, etc. – in order to minimise the risks,” says Bastunets.

In addition to media outlets with editorial offices in Belarus, there is also a large number of freelance journalists who continue to operate in the country but contribute, usually anonymously, to editors in exile.

This carries grave risks. On 30 June, cameraman Pavel Padabed was sentenced to four years in prison after being accused of cooperation with the Polish TV channel Belsat, which has also been recognised as an extremist formation.

There is plenty to report on.

The news two weekends ago that Alyaksandr Lukashenka, whose legitimacy as the leader of Belarus is contested, had acted as a “peacemaker” between Vladimir Putin and Yevgeny Prigozhin provided an interesting story for Belarusian media, both in and outside the country.

Lukashenka promised Prigozhin that could come to Belarus as part of a deal he claimed to have brokered to reduce the tension. Confusingly, he has since announced that Prigozhin is not in Belarus but in St Petersburg (or Moscow).

Most independent media actively covered the actions of Prigozhin and Wagner against the Russian Defence Ministry, with editors and commentators using a variety of terms - military uprising, putsch, coup attempt, march of justice, conflict – to describe it.

“State-run media outlets focused on ‘praising’ Lukashenka's role in settlement of the conflict, which is questioned by many independent experts,” says Bastunets. “It is unknown whether Prigozhin and Wagner Group mercenaries are now in Belarus and whether they were or will be here at all. But there is a feeling that the Wagner mercenaries will not be welcome guests.”

If Prigozhin does turn out to be in Belarus, the country's independent media are still there to report on it.

13 May 2023 | News, United Kingdom

The heavy-handed treatment of anti-monarchy protesters at King Charles III's ceremony is ominous

We are still reeling from the events of last weekend when a series of protesters were arrested in London. The protesters, from the anti-monarchy group Republic, had liaised with the police in advance and been given the green light for their demonstration. Despite this they were arrested as soon as they turned up, with no reason given. They spent the day in jail.

This overreach by the police is, sadly, part of a broader pattern of peaceful protesters and journalists reporting on these protests being arrested, all of which has been exacerbated by the passage last week of the Public Order Act 2023 - which Index has opposed from the get-go.

Commentators have raised the alarm bell. We're sleep walking into a dictatorship, some have said. Others have warned of the UK turning into an illiberal democracy, like Hungary. So what lessons can we learn from other places that have seen their rights to protest crumble? We asked a series of people - artists, journalists and activists - to share messages with us here.

‘Akrestsina prison wasn’t born in a day’

I read Julian Assange’s letter to King Charles III from HMP Belmarsh. I recognise the prison he describes. 1,768 political prisoners in Belarus recognise it. Thousands of Belarusians who took to the streets for peaceful protests recognise it. The name of the prison is insignificant. When I tell people in so-called “first-world countries” that I spent nine days in prison for a peaceful demonstration in Belarus, they get shocked. We come to these countries for security and protection, because we believe that the rule of law works there. Who will protect their own citizens from their state?

As I followed the news from Coronation day, I questioned: why is the smoothness of the show more important than an individual’s right for freedom of assembly? Why is it so much more important that a bill is passed to make detentions of the organisers legal. They were detained before the protest even began. I remember police in Minsk in 2020 arresting us as we walked from different parts of the city, trying to gather in one spot. I remember the Belarusian oppositional candidate Uladzimir Niakliayeu being beaten up and arrested on his way to the protesters on the post-election night on 19 December 2010. I don’t remember it but I read about the opponents of Lukashenka disappearing in the 90s…

Do you think I’m dramatising and it won’t happen in the UK? Not to that extent? Akrestsina prison, this torture chamber where 53 women were kept in a cell for eight, listening to the screams of men raped with a baton on the corridor, wasn’t born in a day. It is the Frankenstein of a society which disregarded the detentions and calls of activists. Don’t let Britain become Belarus.

Hanna Komar, poet and activist from Belarus

'Authoritarian governments are watching closely'

After Hong Kong finally lifted its last pandemic restrictions in March this year, the first protests were authorised in more than three years. Ever since coronavirus arrived in the city in January 2020, the pandemic had been used as a pretext for banning demonstrations, giving rise to absurd situations where it was legal to gather in a restaurant in a group of 12 but illegal to congregate outside in groups of more than four. Protests still happened during that time, particularly in response to the introduction of the National Security Law in June 2020, but once the Hong Kong government raised the fine for violating the four-person assembly rule to HK$5,000 (£500), many people were deterred. Nonetheless, a blind eye was turned to larger groups who turned out to support the government.

When it became legal to protest again, there were a lot of strings attached, often literally. In March protesters against a proposed land reclamation project and waste-processing facility were forced to wear number tags and walk in a cordoned-off line with heavy police presence, while the organisers had to agree not to exceed the permitted 100 participants. Another march, for women’s rights, was cancelled by organisers after police said there was a risk of violence. Former members of the now-disbanded Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions called off a May Day march after one of the organisers was harassed by police.

The right to protest in Hong Kong is now severely circumscribed, to the point that to do so is to invite police attention designed to deter turning out. The National Security Law has also had a chilling effect on people, who might be fearful of losing their job if they take to the streets. The Hong Kong government continues to claim there is freedom of assembly but, like many freedoms in the city these days, it is highly conditional, even hollow.

Tens of thousands of Hongkongers have moved abroad in the past few years, to Taiwan and Singapore, and also to Western countries, including the UK. For many, it is a refuge away from the deteriorating situation back home. But some are also conscious of how things are not perfect in their new adopted countries. The UK’s Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act, with its emphasis on disruption, has aspects that are similar to restrictions back in Hong Kong, while in France, many have been shocked by the brutality of the police in repressing protests against the government’s pension reform law. Unlike in Hong Kong, there is still the possibility of legal recourse against these measures, but Western countries ought to be aware how their repressive tools undermine their own criticism of governments such as China’s and Hong Kong’s. When British police arrest anti-monarchy protesters, authoritarian governments are watching closely, and are only too happy and eager to use this as a justification, however disingenuously, next time they round up protesters on their own turf.

Tammy Lai-Ming Ho, poet from Hong Kong

'Continue standing up for your voice'

Hungary has a long history of protests. In March 1848, a group of intellectuals kicked off a demonstration against the Habsburg empire, which led to the creation of the dual monarchy after a year-long fight. In 1956, university students sparked a mass protest against the USSR, in which over 2,000 people were killed, but which ultimately resulted in a softer governance. It was a series of protests that led to the toppling of Hungary’s last socialist PM, Ferenc Gyurcsány, too, following the leaking and broadcasting of a profane and controversial speech in 2006. A young right-wing party, Fidesz, organised multiple protests.

Ultimately, these events and Fidesz’s role contributed to the election of party chair Viktor Orbán in 2010. Since then, he has been leading the country into an increasingly anti-democratic future, including cracking down on protesters’ rights.

The country has witnessed plenty of protests since, despite increasingly strict laws and growing retaliation. In the latest, students marched against the restrictions of freedom of teachers. Two events, held one week apart in April and May, were both ended by the police spraying tear gas, in some cases directly in the faces of minors.

The popularity of these protests shows that the Hungarian youth isn’t keen on standing down and giving in to a future without voice, joining youth around the world, be it protesting against monarchy, for pensions or human rights.

Videos of this protest see visibly young people tearing down the metal fence in the Buda Castle, climbing on buildings and chanting the mantra of protests around the world: we won’t allow this.

“This shows that we got under someone’s skin, we started doing something… And maybe we will get even more under their skin,” one young protester said when asked why she persists, by the independent portal Telex.hu. Perhaps this should be a message for all protesters around the world: to continue standing up for your voice and displease those who are trying to take it away.

Lili Rutai, journalist from Hungary