#IndexAwards2017: Bill Marczak uncovered the selling of iPhone spyware to corrupt governments

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A schoolboy resident of Bahrain and a recent PhD student in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, Bill Marczak co-founded Bahrain Watch in 2012. Seeking to promote effective, accountable and transparent governance, Bahrain Watch works by launching investigations and running campaigns in direct response to social media posts coming from activists on the front line. In this context, Marczak’s personal research has proved highly effective, often identifying new surveillance technologies and targeting new types of information controls that governments are employing to exert control online, both in Bahrain and across the region. In 2016 Marczak investigated several government attempts to track dissidents and journalists, notably identifying a previously unknown weakness in iPhones that had global ramifications.

Index spoke with Marczak in the run up to the Freedom of Expression Awards, where he is nominated for the Digital Activism award.

Ryan McChrystal: In the summer of 2016 you discovered a previously known weakness in Apple’s iPhone that had global ramifications. Can you talk us through how that first came to light?

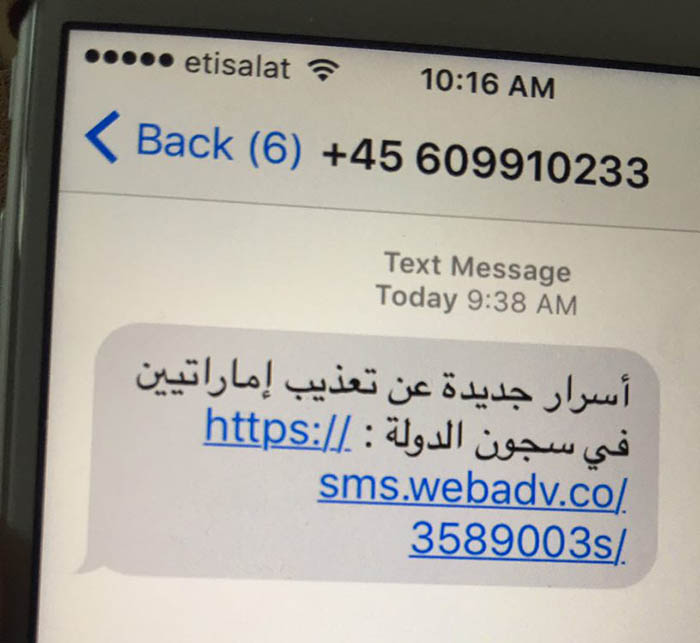

Bill Marczak: In August of 2016, Ahmed Mansoor, an activist in the UAE, reached out to me after he had received suspicious text messages. I had known him previously because he gets suspicious things in his inbox or on phone quite frequently. He sent me these text messages and asked me to take a look. The messages said: “New secrets about detainees tortured in UAE prison.” And there was a link inside the text message which I recognised because it was connected to a series of websites I had been tracking for the past six months or so. I had already attributed them to the NSO Group (an Israeli spyware company).

At that point, I was able to get the spyware they were using to target Mansoor

McChrystal: What does the software actually allow governments to do? What are the dangers for activists?

Marczak: The malware that NSO sells, called Pegasus, is actually pretty sophisticated in what it can collect. In the security community, the iPhone is generally thought to be more secure because Apple goes to such lengths to lock down and make it really, really hard to install an application from outside the App Store and to do something to the device that’s not approved by Apple. The fact that this malware even existed and could affect an iPhone in the single touch of a button was very surprising. Once your phone is infected, the malware would essentially be able to see everything on the device. If you had any saved passwords, for example, they would all be sent back to whoever infected you. That person would also get the ability to intercept your calls, SMS, Whatsapp, Viber, or any other communication service you use.

Perhaps most scarily, the malware allowed the user to turn on the webcam and the microphone on your iPhone to spy on activity going on around the phone. This could be used to spy on meetings or to see who you were hanging around with.

McChrystal: And this was was the first piece of malware of its kind.

Marczak: That’s correct. It was the first known zero-day remote jailbreak for the iPhone that was used as part of spyware. A jailbreak is a piece of software that allows you to get around Apple’s security precautions for the phone. Jailbreaking started out as a way for hobbyists and enthusiasts to install their own software not approved by Apple on the iPhone, so it was a very innocuous line of research. But once iPhones became more popular, people started putting their whole lives on their phones. That’s when jailbreaks became really, really valuable to people who would want to spy on iPhone users.

Nowadays, there are companies that will pay you if you sell them software or the code that jailbreak the phone. Some companies, like Zerodium, offer up to $1.5m. Presumably they’ll then be able to sell it to interested users for even more.

McChrystal: How did Apple respond when you informed them of your discovery?

Marczak: Working with the folks at Citizen Lab, I got in touch with Apple very early on in the process to alert them of what we had found. Initially, when we called up Apple was like: “Yeah, yeah, sure, send us some details and we’ll take a look.” When we sent what we were able to pull down from those links, the tone changed right away and they realised this was really serious. They said: “Give us more information because we want to work closely with you on this.”

McChrystal: How are governments using this kind of malware maliciously? And why should human rights activists specifically be worried?

Marczak: This kind of software can be used, for instance, in legitimate criminal investigations, but it can also be used essentially for anything the government wants to use it for. Once NSO Group sells the spyware to a government, that’s where NSO’s ability to control things ends. The government can then decide who it wants to target, who it wants to infect. If sold to a government agency that has a history of abusing surveillance, it’s likely they are going to abuse it to target human rights defenders and political opponents.

It’s something that human rights activists should be concerned about because everything is moving online these days. They are on their phones, communicating with other activists, human rights violations are being documented by videos or pictures on the phone. Your confidential or secret sources might be a WhatsApp contact, or a Signal contact if you’re even more secure.

If just one person has been infected, governments can map out an entire network of human rights defenders or opponents. They can keep tabs on an entire operation or human rights infrastructure in a country.

McChrystal: By bringing this malware to light, how many people’s privacy do you think you’ve helped to protect? Is there a way to put a number on it?

Marczak: The patch that Apple released, which coincided with the report that I published with Citizen Lab, went out to every iPhone user around the world. Apple subsequently issued a patch to every Mac laptop and desktop user. The number is in the high hundred of millions, if not billions of people whose phones and computers were patched.

Of course, not all of those people would have been affected, but having that sort of broad impact was very exciting.

McChrystal: Are you yourself now in danger of cyber attacks? Have there been any attempts that you’ve noticed?

Marczak: It’s something that I’ve thought a lot about. If you look at the security industry as a whole, researchers themselves can be very easily targeted. There have been instances where foreign intelligence agencies have targeted anti-virus companies, for instance, to figure out what they are working on next.

That’s the main risk I am worried about: if some foreign intelligence agency decides “hey, Bill’s working on some interesting stuff. Let’s hack him and see what he’s up to.”

When I’ve done some work in the field, for instance in the Middle East, I think through a set of operations security procedures like how to prevent someone coming into my hotel room when I’m away and bug my laptop.

McChrystal: What’s your connection to Bahrain and how did that lead to the establishment of Bahrain Watch?

Marczak: My own connection with Bahrain began in 2002. I went to high school there because of my dad’s job. Going to high school in a place, you obviously develop a lot of connections and experiences that tie you there, at least emotionally. Bahrain very much feels like one of my homes.

While I was there, I was never much interested in the political situation. But going back to the USA for college and observing from abroad, I did start to notice by reading the international media that there were certain things not right with the country, especially in 2011, when the Arab Spring protests started. Once I saw that police were shooting protesters in the street, and that one of my homes was in crisis, I though if there was a way that I, a computer science student sitting in Berkeley, California, could do anything to have a positive impact on the situation.

At the time, I didn’t really know what to do. I started following Bahraini activists, people on the ground and those who were actually at the protests. Those involved in the Arab Spring very much engaged with the rest of the world through social media. They sometimes sent out pictures of shotgun shells or tear gas canisters, asking if anyone knew who was manufacturing and supplying the government with them.

I was able to respond to these requests and see if I could find out some new information. I started off doing research into the various kinds of weapons that the police were using. That initial research got me some recognition among activists on the ground. We got in touch and developed connections which led us to decide to found Bahrain Watch in 2012.

Bahrain Watch initially focused on these arms, but them later expanded to documenting western PR companies that the government had hired to influence the media narrative. It expanded from there to a bunch of different areas.

McChrystal: The situation for human rights activists in Bahrain is changing, and in many ways it’s become more difficult. What does this mean for Bahrain Watch operations over the next year?

Marczak: You’re definitely right that the situation on the ground is very bad. In the past year we’ve seen the continued harassment of human rights defenders on the ground. One of the things we are trying to do going forward is to is, we started off in 2012 as an all-volunteer organisation and we were very much sustained by the energies and the passions of the Arab Spring.

But in the years since, a lot of that energy has died off to an extent, not just in Bahrain, but in the broader activist community. One of our challenges going forward has been to try and formalise the organisation so that we’re actually getting funding and have the capacity and resources to undertake more longer-form types of work. We’ve got some of that already, we have gotten a bit of funding, and we’re looking mainly to continue our work with digital security, so trying to provide support and advice to dissidents on the ground to help enhance their security posture, given the ongoing crackdown by the government.

At the same time we want to do more broader types of investigations into corruption more closely into the government’s strategy of controlling the media.

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2017 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490258649778{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/donate-heads-slider.jpg?id=75349) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1491488367891-c15491ac-4f30-3″ taxonomies=”8734″][/vc_column][/vc_row]