Baku 2015: The foreign manpower behind Azerbaijan’s games

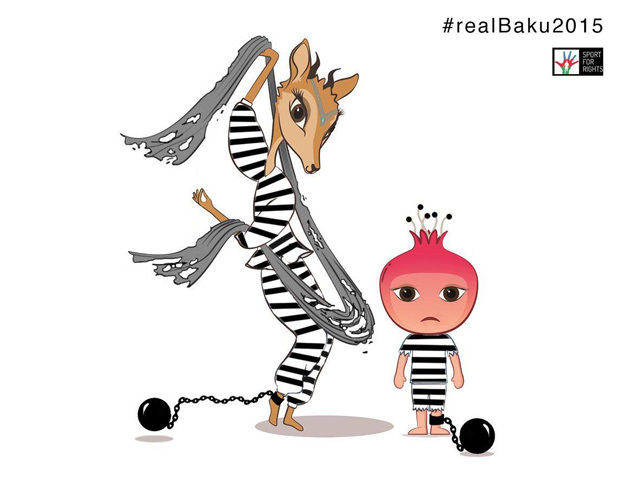

Human rights groups hijacked a hashtag used to promote a contest to win tickets to the opening ceremony of the Baku European Games (Photo: Amnesty International)

President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan has high hopes for the European Games; the brand new, European Olympic Committee-backed regional sporting event which kicks off Friday 12 June in Baku. According to the organising committee BEGOC, Baku 2015 — with an estimated price tag of some £5.4 billion — will “showcase Azerbaijan as a vibrant and modern European nation of great achievement”. But it seems the event is not down to Azerbaijani achievements alone: from promotions to operations, foreign manpower has played a significant role in making Baku 2015 a reality.

Brit Simon Clegg, former chief executive of the British Olympic Association and Ipswich Town football club, is the CEO of the games. He took over when American Jim Scherr, who has previously overseen US Olympic teams, stepped down in 2014. Dimitris Papaioannou, the Greek artistic director of the opening ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympics, will reprise this role in Baku. Meanwhile, British marketing firm 1000heads was behind a social media competition to give away tickets to the show. James Hadley, Cirque du Soleil’s senior artistic director, will take the reins of the closing ceremony, with the help of creative director Libby Hyland, who previously worked on the Pan American Games. The promo video was directed by American Joel Peissig, signed to the production company of Oscar-nominated filmmaker Ridley Scott. UK/US-based major events company Broadstone is taking care of day-to-day business on the ground, from transport, to human resources, to security. And the list goes on.

Sporting stars have also made their mark even before the start of the games. “Baku 2015” has for months been emblazoned on the shirts of Spanish football giants Atletico Madrid. A number of participants — from British taekwondo athlete Jade Jones, to French rhythmic gymnast Kseniya Moustafaeva, to Serbia’s 3×3 basketball team of Dušan Domović Bulut, Marko Savic, Marko Zdero and Dejan Majstorovic — have been named international athlete ambassadors.

While most contemporary mega sporting events are, to an extent, multinational operations, the situation in Azerbaijan follows a familiar pattern. The oil rich country — ruled by President Aliyev since 2003, when he took over from his father Heydar — has for some time relied on foreign input in its ongoing international rebranding project. Meanwhile, the government has been cracking down on human rights at home.

Take for instance the modernisation and beautification of downtown Baku. The flame towers dominating the skyline were designed by global architecture firm HOK. The in-demand London-based design studio Blue Sky Hospitality has worked on over a dozen restaurants in the city over the past five years. This includes at least five in Port Baku, dubbed the city’s “premier luxury address” by the glossy, internationally distributed magazine edited by the president’s daughter Leyla Aliyeva. Azerbaijan has also worked with foreign public relations companies, such as the Berlin-based Consultum Communications and global firm APCO, with headquarters in Washington. The government even hired former British Prime Minister Tony Blair as an advisor in 2014. According to independent news site Contact.az, the government in 2011 allocated AZN 30,000,000 (£18.7 million) in the state budget to promoting Azerbaijan, though this figure is thought to be an underestimate.

But the push to paint Azerbaijan as a forward-looking state has not translated into progress on the human rights front. Over the past year alone, the country’s most prominent critical voices — including investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, human rights activists Leyla and Arif Yunus, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and pro-democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov — have been jailed on charges widely dismissed as trumped up and politically motivated.

Critics believe the government, with the help of overt foreign PR and the prestige of working with well-known international names, is presenting a sanitised version of Azerbaijan to the world, to whitewash its poor rights record. In other words: the government targets those challenging its representation of Azerbaijan, and the PR blitz in turn masks the crackdown. “We are facing a huge PR and propaganda machine from Azerbaijan supported by oil companies in the west,” Azerbaijani journalist Emin Milli said at an expert panel debate ahead of the games.

“The Aliyev government has used the revenues of the oil and gas fields to finance a stream of grandiose projects — from the Heydar Aliyev Airport, to the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre and the European Games. In the realisation of these projects it has hired a number of international corporations. British companies are particularly heavily involved, for example in constructing the airport, designing the centre, and co-ordinating and branding the games,” said James Marriott from the London-based NGO Platform.

Or, as Simon Clegg told The Independent in 2014, British companies “are absolutely at the forefront of winning contracts over here [Azerbaijan] for the successful delivery of the games”.

Platform’s campaigning is focused around BP, the British oil company which has long worked in Azerbaijan and is one of the lead sponsors of the games. “In binding itself so closely to these foreign corporations the Aliyev government is building the international political support that it recognises is so vital, especially as it tries to counter the growing dissent in Azerbaijan,” added Marriott.

Rebecca Vincent coordinates the Sport for Rights campaign, which has worked to raise awareness around the crackdown on government critics in the lead-up to the games. The movement was initiated by Rasul Jafarov before his arrest. Those wanting to raise human rights issues are “fighting this massive army of very well paid PR firms throughout Europe,” said Vincent.

“The Azerbaijani government’s PR has been quite effective. They have been successful in promoting Azerbaijan as this modern, glamorous country. We’re working very hard to show that there is more to the story; that there is a more sinister side,” she added.

According to Azerbaijani journalist Arzu Geybulla, reaction from her countrymen and women to their government’s strategy has been mixed, and dependent on how much information they have. Some are simply preoccupied with putting food on the table and are unaware of the extent of foreign involvement; others, often young and western-educated, know what’s going on, but are reluctant to challenge the status quo directly.

She categorises foreign companies and individuals working in Azerbaijan in a similar way. Some, she says, know nothing about Azerbaijan and are just there to take the opportunity given to them. Others have limited understanding of the state of human rights in the country, and “care very little about imprisoned journalists or beaten bloggers”. The final group, where she places the EOC, is fully aware of situation on the ground, “and yet they’re saying that athletes are coming there to compete, and the crackdown shouldn’t prevent a sports competition taking place”.

Index queried a number of individuals and firms associated with the games.

One person was willing to speak on the condition of anonymity. While stressing that the presence of international staff and companies is business as usual for large sporting events, the source dubbed the situation at the Baku Games “a little bit weird”, especially noting the “big British connection”.

The person said they didn’t know much about Azerbaijan or its political climate when taking on the job, but spoke of their shock upon arriving in the capital. “Baku is like Monaco crashing into Tijuana … it’s one giant set,” they said, dubbing it a city of facades. “It seemed pretty desperate.” Though the source said they would consider speaking out about the situation, they worried about the impact it might have on the locals they worked with.

1000heads, the London-based company behind #HelloBaku (a social media competition which was hijacked by activists to draw attention to human rights and free speech violations in Azerbaijan), told Index they are no longer involved in the games.

As for athlete ambassador Jade Jones, she says she is focusing purely on the sporting side: “We go to different places. Some places are better than others. I’m just going there to do my job and perform.”

Clegg, meanwhile, has stood firm when pressed on human rights concerns: “Look where they’ve come from – decades of Soviet rule and oppression,” he told The Guardian. “You don’t go from there to there overnight. If you do, you end up with chaos and civil disorder.”

This echoes the government narrative, which describes of a country that may not be perfect, but that is on the right track. “Azerbaijan, as a young democracy and dynamically developing country, which demonstrated goodwill in hosting the first Baku Games, deserves appreciation and understanding, too,” a foreign ministry spokesperson told the BBC.

But with the ongoing jailing and judicial harassment of vocal critics of the government being widely labelled an unprecedented crackdown, many disagree with this interpretation. Council of Europe human rights commissioner Nils Muižnieks co-wrote a recent op-ed arguing that human rights cannot be ignored during the games, and encouraging athletes going to Baku to use their platform to speak out. Some seem to have already taken him up on this: German athletes last week called for the release of Azerbaijan’s political prisoners. “Although I do not usually address directly private companies, I can say that I would like to see the business field taking into more consideration human rights related issues which may arise from its activities,” Muižnieks told Index.

On the day of the opening ceremony, Jafarov will be going back to court. With this, Rebecca Vincent says the government has the opportunity to send a message more powerful than the sure to be spectacular show taking place in Baku National Stadium. “I’d remind the Azerbaijani authorities that the best PR would be to stop the human rights crackdown and release the political prisoners,” she said.

“Rasul’s release would be a step in the right direction.”

This article was posted on 9 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org