23 Apr 2025 | Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Palestine

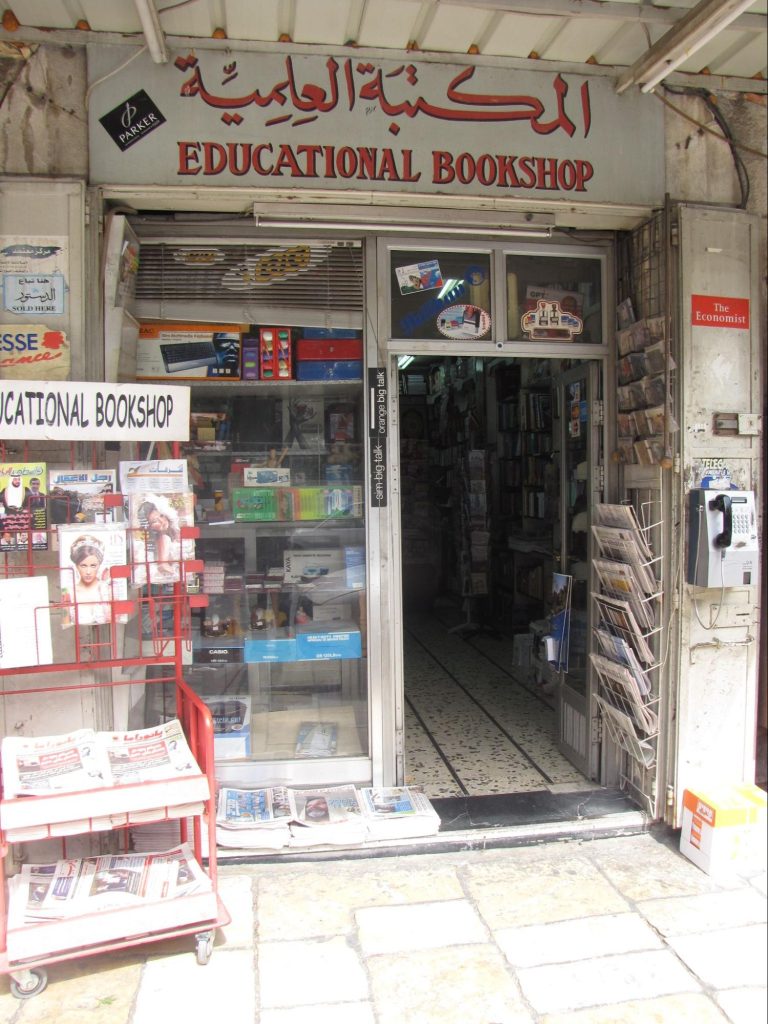

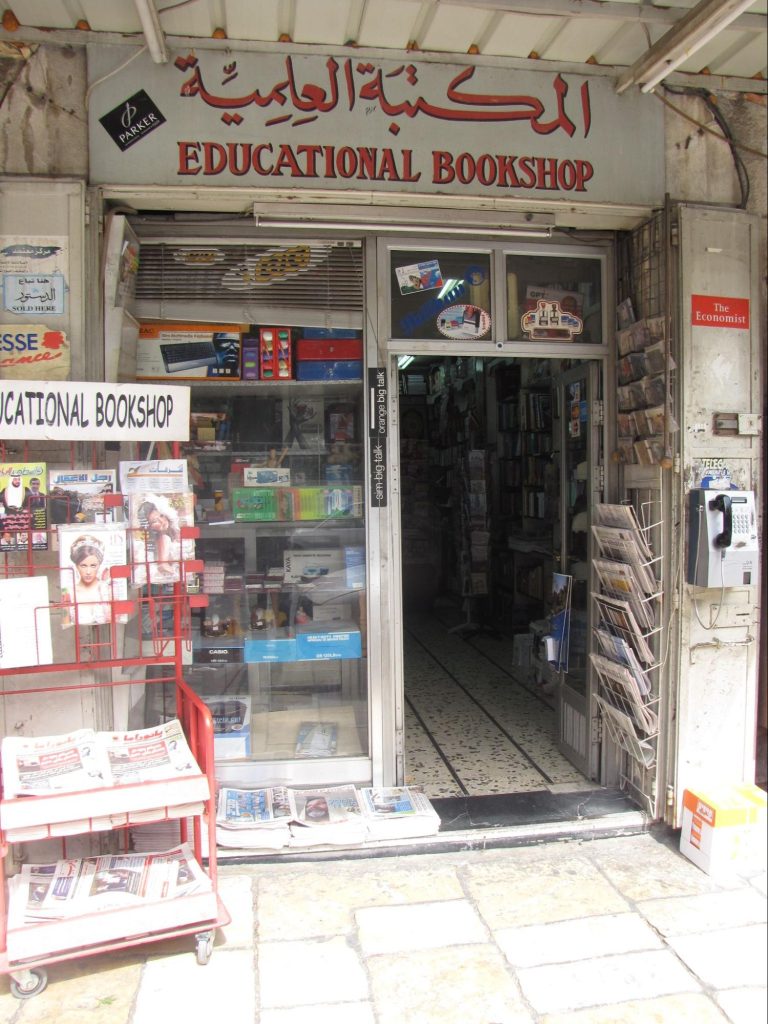

For more than 40 years, the Palestinian-run Educational Bookshop in occupied East Jerusalem has provided both locals and tourists with access to a wealth of books, magazines and cultural events, establishing itself as a cultural hub within the historic city. Now, its very existence is under threat.

On 9 February 2025, undercover Israeli police stormed the bookshop and its Arabic-language counterpart next door.

“It was a Sunday afternoon. I was having a good time with my daughter who’s 10 years old,” Mahmoud Muna, co-owner of the bookshop, told Index on Censorship.

The officers started pulling books from the shelves and examining the covers.

“Any cover that had a flag, map, words, keywords like ‘Palestine’, ‘Nakba’ or ‘Gaza’ was deemed suspicious,” said Mahmoud. “Then they Google translate[d] the cover or the blurb or the back page, and they start[ed] creating two piles on the floor, one for the books that they didn’t want to take and another pile for the books that they wanted to take. [This was] completely irrespective of the books and what they mean to us.”

The police put around 300 confiscated books into bin bags, then took Muna and his nephew Ahmad Muna into custody on charges that their books were causing “public disorder”.

“They took us to the police station where we were detained the first night and then taken to court the second night… we were released after 48 hours, myself and my nephew, who was manning the Arabic branch. [We were put] on bail: five days’ house arrest and 20 days away from the bookshop.”

Most of the confiscated books were returned. On 11 March 2025, the police raided the bookshop again, taking 50 books and arresting Mahmoud’s 61-year-old brother and co-owner, Imad Muna. Imad was released a few hours later. The police confiscated books by Banksy, Ilan Pappé and Noam Chomsky, among others.

“They came again and they replayed the whole scenario again. It was just that we were a bit more ready legally. It happened during the morning hours and it was my brother who was in the shop. So we were able to act very quickly and [he was released] before the night,” Mahmoud said.

The Educational Bookshop was founded in 1984 by Mahmoud’s father, Ahmad Muna, a Jerusalem-born teacher. The bookshop has remained a family business ever since.

“For 40 years, we’ve been in operation, trying to serve our community, trying to contribute to social, political, cultural change in a city that is torn between political upheavals. And we believe that books and conversation around books can be an important carrier, if you like, for the conversation. It can open up a space for conversation,” Mahmoud said.

Photo by Mahmoud Muna

These raids are not isolated incidents; they form part of a wider campaign by the Israeli government to crack down on free expression, which has been intensified by the emergence of the far-right within Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government and worsened still by Hamas’s incursion on 7 October 2023 and the war in Gaza that has followed.

Recently, authorities have also begun censoring Israeli films critical of the government, as well as events and festivals that discuss Gaza, Palestinians or the 1948 Nakba. The government has started using a revived British Mandate-era law from 1917, which allows the Culture and Sport Ministry to review films before they are screened.

“I think the political climate has really changed. Maybe the war is part of that, but it is not the reason. There is a policy of oppression towards cultural institutions. If you look at theatre, music schools, youth clubs, women’s associations for the last five, six, seven years even before the war, they have been suffering,” Mahmoud said.

Mahmoud says that he and his family have no intention of giving into the authorities’ intimidation tactics.

“We are determined, we’re not gonna give up. It makes me angry, but it also makes me believe even stronger in the power of books and words and literature. And it also opens my eyes even further to the importance of our work in our society.”

Above all, he calls on the international community to speak out against the erosion of democratic values unfolding in Israel and Palestine today.

“If we really believe in what we say, and we really want progressive liberal societies and freedom of expression in Turkey or China or Russia, then we also need to demand them in places like Jerusalem as well.”

6 Mar 2025 | News and features, United Kingdom

Today, my son trotted off to school in a hastily assembled knight-doctor-dragon combo, firmly taking on his role as the knight from Zog, whose name I can never get right. Sir Galahad? Sir Gallopalong? Ah yes, Sir Gadabout. This was his first World Book Day, and as a book-loving writer mum, it was quite the moment.

Aside from fond memories of my own childhood World Book Days dressing up as Ratty from The Wind in the Willows (including homemade tail) and Hermione from Harry Potter (hair my own), I now have another reason to love the annual literary celebration.

Last summer, we at Index published an investigation into book censorship in UK school libraries. I have been following the worrying trend of book bans in the USA for several years, and I wanted to know whether any of that censorship is creeping into UK schools. I found out that yes, it is.

In the survey I sent to school librarians, 53% of respondents told me they had been asked to take books off their shelves. And 56% of those actually removed the books in question. When I spoke with librarians directly, many had been left shaken by their experiences.

The censored books largely featured LGBTQ+ content, as well as other areas. In one school, the entire Philip Pullman collection was removed by a senior staff member in a school with a Christian ethos. In another, all books with a hint of LGBTQ+ content were boxed up and left to gather dust.

Since publishing my investigation, even more librarians have been in touch to tell me about censorship in their schools, often telling me how lost they feel. There is no statutory requirement for a school to even have a library in the UK, let alone there being any official policy.

Recently, someone reported to me that when pupils were invited to take books into class, a child who brought a copy of Room on the Broom was swiftly turned away. They were told that they couldn’t read it because it is a Christian school. For anyone who doesn’t know this Julia Donaldson staple (that’s the second Donaldson mention in this piece, so that gives you a sense of how popular her books are), it’s about a witch, and a series of events that means she – you guessed it – does not have room on her broom.

I can’t help imagining how that child felt to have their choice of book rejected, butting up against censorship at such a young age, and being told that their favourite book was “wrong”; the parents or carers of that school second guessing what they might be allowed to send their child into school with; and then suddenly, there is a culture of self-censorship in that school.

World Book Day, in part, is a bit of a pain for parents. Costumes can be time-consuming to make or expensive to buy, and plenty of households up and down the country awoke this morning to a chorus of “World Book Day is today?” Children are ushered out the door, assured that a t-shirt and shorts is actually a very acceptable costume for the kid in insert any ordinary child in any book ever written.

But for me, in spite of whatever costume dramas might arise in the coming years (I may eat my words when that day inevitably comes), it’s a day to celebrate a love of books. And that means fighting for them.

As culture wars continue to heat up in the USA, it’s important that we do not let that slide into our classrooms, and that classrooms do not become battlegrounds. Just as it’s important that a child is not shamed for bringing in Room on the Broom, it’s vital that young people must be able to access stories where they can see their own experiences (and those of their peers) reflected.

Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love is one of our favourite stories at home. It is beautifully illustrated, and tells the tale of a boy who wants to dress up as – even imagines he is – a mermaid. He is encouraged to use his imagination by his grandmother, and he is not shamed for exploring his identity. It’s not only a gorgeous story, but a lovely way to introduce young children to discovering who they are and how others around them might explore their own identities too. Despite this, it was one of the books that librarians in my investigation reported as having been banned.

Stories help us understand the world, and they help us understand ourselves. They help us navigate things that are scary, complicated and confusing. They help flex our imaginations. And they’re joyful.

I do not want our schools to face the level of censorship that many schools in the USA do, and for our librarians to be fighting off book challenges instead of helping children find their next great read. I don’t believe widespread book bans are a real threat right now, but we now have evidence that there are pockets of this happening across the country. So this World Book Day, I’m going to harp on again about the importance of the freedom to read, and keeping our schools free from book bans.

If you care about books as much as I do (and why wouldn’t you?), please join me in celebrating books, and kicking up a fuss about the importance of good school libraries, where librarians are empowered to curate a diverse and creative collection.

19 Feb 2025 | Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Palestine

Israeli authorities are silencing Palestinian culture and history in a censorship surge that could soon include left-wing Jewish opponents of Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition, academics have said.

Last week, Israeli police raided the Educational Bookshop in East Jerusalem, one of the most prominent Palestinian cultural institutions in the occupied territory. Two of its owners, Mahmoud Muna and Ahmad Muna, were arrested on suspicion of “disturbing the public order”, interrogated, detained for 48 hours, then placed under house arrest for five days.

“I assume the next stage will be the Israeli left,” Menachem Klein, an Israeli political scientist and emeritus professor at Bar Ilan University, told Index after this event. “We are on the way to an authoritarian regime during ongoing wartime and it is easy to use emergency rules to silence freedom of expression.”

During the raid, detectives allegedly inspected books using Google Translate and took away ones they deemed to be possible incitement to terrorism because they contained words such as “Palestine” or “Hamas”.

One of the books presented as proof of possible incitement was a children’s colouring book titled From the River to the Sea, which was allegedly found in the store’s warehouse. The phrase, which has proved controversial, is used by some to imply that Israel should be replaced by a Palestinian state from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Critics have labelled this confiscation laughable – in a comment piece, Haaretz ridiculed that a children’s colouring book is being “considered a ticking time bomb”. But government supporters have said that the book does constitute incitement.

There has so far been no criticism of the raid from any major Israeli opposition leaders, but a member of the Knesset (MK) for the left-wing Democrats party has allegedly filed a query in parliament questioning the police’s actions. Prominent Israeli authors and cultural personalities have also spoken out about it. However, the absence of broader political opposition means the authorities are unlikely to be deterred in the future from widening their targets on cultural institutions.

“We’ve undergone a change in Israel whereby anyone who incites to terrorism has to pay a price regardless of whether he is Arab or Jewish,” said Shamai Glick, head of the right-wing organisation B’tsalmo, told Index. He argues that authorities did not go far enough and should close the bookstores.

This recent intimidation comes amid crackdowns on Israeli films that are critical of the government, especially those dealing with alleged crimes related to the mass displacement of Palestinians during what Israelis term the 1948 War of Independence and Palestinians term the Nakba, or “catastrophe”.

In December, Israel’s Minister for Culture and Sport Miki Zohar threatened to halt government funding for the Tel Aviv Cinematheque after it showed films deemed to be pro-Palestine at Solidarity Human Rights Film Festival 2024.

One of these films was the previously-censored Lyd, which depicts the 1948 expulsion of that town’s Palestinians and imagines what Lyd would be like if not for the Nakba. Two months prior, the police had banned a screening of Lyd in Jaffa after Zohar said the movie was “inciting and mendacious” and “slanders Israel and Israeli soldiers”.

Cutting government funding to a cultural institution in Israel is a death sentence, as there is little private investment in the arts. In a letter to the Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich, Zohar wrote that the Solidarity Festival had shown films that “are against the state of Israel” and which “disparage the soldiers of the Israel Defense Force[s]”, according to the Jewish Independent. Smotrich has set up a committee to determine whether the festival violated funding laws.

Lyd co-director Rami Younis said the recent raid on the bookstore should be seen as an escalation of national cultural censorship. “This is another syndrome of the rise of fascism. Are books the enemy? We’ve seen regimes in the past that declared books and songs the enemy. And they’re all dark regimes and this is where Israel is heading.”

“If it’s not stopped, it will get much worse very soon,” he said.

The government has also started deploying a little-used British Mandate-era law dating back to 1917, which allows the Culture and Sport Ministry to review films before they are shown at cinematheques, thereby stopping screenings of contentious films.

According to Haaretz, the Israeli Culture and Sport Ministry’s Film Review Council warned cinematheques in November not to screen filmmaker Neta Shoshani’s documentary film 1948: Remember, Remember Not, as it had not been granted the council’s approval. The film, compelling and thought-provoking, looks at the War of Independence / Nakba through testimonies and interviews with Israelis and Palestinians. The film lost several screenings as a result, but ultimately was approved by the council.

In response to the request, cinema directors said they had not been asked to clear films with the council previously. Normally, the council sets age ratings rather than undertaking political censorship.

Filmmakers and festival organisers in Israel are now being deterred from showcasing work that is critical of the government. The coalition’s threatening behaviour towards art and culture that raise questions about Israel’s foundation, probe Palestinian displacement or allege violations by the Israel Defense Forces mean that many cultural workers are steering away from controversial topics.

“When they threaten, you don’t feel like taking a chance,” Shoshani recently told The Jewish Independent. “There is a chilling effect,” she said.

“This means that culture in Israel is rapidly becoming non-critical and doesn’t go to [controversial] places simply because there is no one to fund this type of film. If I enter controversial realms, I won’t get funding and at the end of the day, we all have to make a living. So clearly people exercise self-censorship even though they don’t admit it.”

“This is something that happens under every dictatorial regime,” Shoshani added. “In a fascist regime, culture becomes propaganda and not culture. Gradually, Israeli culture is becoming like that.”

In response to criticism that the Israeli government is impinging on free expression, Zohar’s office said: “We will continue to defend freedom of expression but we won’t let extremist and delusional elements incite and harm under the sponsorship of the state of Israel.”

The censorship of Shoshani’s film also demonstrates how the Israeli state is attempting to stop the public from seeing archival footage and important documentation produced by researchers. The public broadcaster Kan (also known as the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation), which funded the film, has not aired it for more than a year, due to what it describes as wartime sensitivities. “It will be screened soon,” a spokesperson said. Minister of Communications Shlomo Karhi has allegedly pressed Kan to scrap the film entirely, according to Israeli news website ICE (Information, Communication, Entertainment).

But Benny Morris, a leading Israeli historian who appears in Shoshani’s film and who was born in 1948 himself, told Index that it is the government that is distorting and covering up the real events of the War of Independence.

Cultural censorship is also only the beginning of a wave of restrictions on free expression in Israel. The coalition government is currently pushing through other anti-democratic bills, including one designed to restrict the speech of academics, and another that would effectively reduce the ability of Palestinian citizens of Israel to vote in elections and decrease their Knesset representation.

“Yes, there is a government effort to censor and lie about 1948, about Israeli war crimes in that war and hence influence how Israelis see their history,” said Morris. “Along with other subversions by the government of Israeli democratic norms, they are threatening Israel’s culture and historiography and trying to replace truth with propaganda.”

17 Dec 2024 | News and features

What do rainbow-coloured hair extensions, Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Gay Science and Sex Addiction: A Survival Guide have in common? They have all allegedly been swept up in broad censorship measures by retail giant Amazon, according to a new report by The Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary laboratory based at the University of Toronto.

The Citizen Lab, which studies openness and transparency on the internet, analysed the US storefront Amazon.com to uncover restrictions on certain products being ordered from specific regions. They found that the most common product category that is restricted is books, often with themes of LGBTQ+ lives, the occult, erotica, Christianity or health and wellness. These are censored in the UAE, Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries, as well as Brunei Darussalam, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles and Zambia.

But it isn’t just products actually banned in these countries that are restricted. The Citizen Lab uncovered a raft of “collateral censorship” where items were miscategorised (for example, because they contained the word “gay” in their title or description), hence the banning of rainbow-coloured hair extensions due to the word “rainbow”.

When potential consumers from these regions try to purchase various products from Amazon.com, they are given various error messages, such as an announcement that a product is out of stock. But, according to The Citizen Lab’s methodology, these items are not out of stock. The organisation’s research can distinguish between products being genuinely unavailable for delivery in a region, and being restricted.

Noura Al-Jizawi, senior researcher at The Citizen Lab and co-author of the report, told Index that this sheds light on a potential broader strategy around censorship.

“Rather than taking responsibility or openly acknowledging its role in restricting certain content, Amazon masks these decisions as stock or availability issues,” she said. “This tactic allows the company to evade accountability and makes it difficult for stakeholders — customers, authors and publishers — to challenge or appeal such practices.”

She claimed that this helps Amazon to maintain its reputation and avoid accusations of censorship, as restrictions are framed as logistical problems rather than deliberate decisions. But transparency, she explained, is crucial.

“If a book has been miscategorised or unfairly censored, users have the right to appeal such decisions,” she said. “Similarly, authors and publishers deserve the opportunity to request Amazon to reconsider its decision to restrict their work. Without transparency, these stakeholders are left in the dark, unable to understand or address the reasons behind such restrictions.”

Jeffrey Knockel, senior research associate at The Citizen Lab and another of the report’s co-authors, told Index that his organisation had previously identified censorship on the Saudi Arabia and UAE Amazon storefronts, and were trying to systematically measure which products were blocked when they realised that the same censorship existed on Amazon.com.

The Citizen Lab has written to Amazon to inquire about the pressure the conglomerate might be under from various governments. They have also made recommendations, including that Amazon should “provide transparent and accurate notifications to customers when products are unavailable due to legal restrictions of the destination region” along with details on the relevant law and a mechanism for customers to flag improperly classified items. At the time of publishing, Amazon has not replied to The Citizen Lab.

Yuri Guaiana, senior campaigns manager at All Out, a global movement campaigning for LGBTQ+ rights, spoke to Index in response to the report. He believes Amazon should implement The Citizen Lab’s recommendations as a first step, but should then go even further.

“As a global leader, Amazon has the power to influence norms. It should take a stand against oppressive laws that force censorship, actively working with human rights organisations to advocate for change in restrictive regions,” he said.

All Out has launched a petition demanding that Amazon stops censoring LGBTQ+ books. “For businesses like Amazon, complying with oppressive local demands may seem like a pragmatic choice, but it risks reinforcing systemic discrimination,” he said.

He echoes The Citizen Lab’s concerns around lack of transparency around censorship, which he says shields “both Amazon and oppressive governments from scrutiny”.

If there was better transparency, he explained, customers and human rights campaigners would be more equipped to push back against unjust restrictions and oppressive laws.

He also shared concerns about the issue of “collateral censorship”. “We’ve seen this pattern escalate in places like Russia,” he said. “After Putin’s regime implemented laws censoring so-called ‘LGBT+ propaganda’, enforcement spiralled beyond media and literature. People have been arrested for as little as wearing rainbow [earrings], showing how quickly such policies can expand into every facet of life,” he said.

Index approached Amazon for a right of reply but Amazon did not respond to Index’s request for comment.