17 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, United Kingdom

I was retweeted by Caitlin Moran on Wednesday evening (#humblebrag). It was a curious glimpse into the world of internet fame. Suddenly my replies were full of retweets and favourites – hundreds of them.

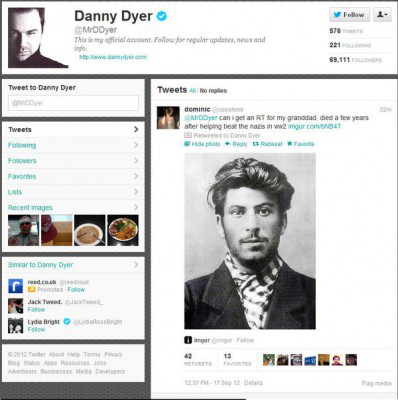

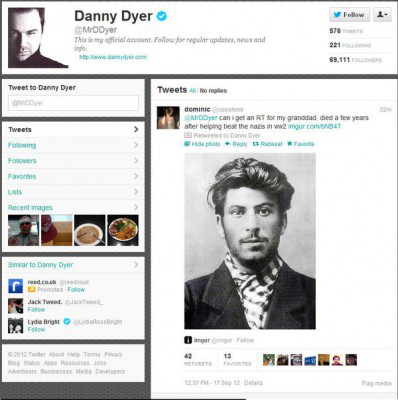

The tweet itself was fairly innocuous; in fact, it was a bit of a cheat. I’d copied someone else’s tweet, adding my own disbelief. And that tweet by someone else was a retweet of a three-year old tweet by well-hard actor Danny Dyer, who had been tricked, quite amusingly, by someone asking for a shout out to his grandad who had helped beat the Nazis, accompanied by a picture of a young Stalin. I’d missed it at the time.

Anyway, on it came throughout the evening, retweets, favourites, questions, statements of the obvious, snark…. It was weird, and unexpected, and kind of exciting. It was like I’d done something really good, rather than just stealing someone else’s old joke. And I was able to track exactly how good it was. I had pulled some kind of killer move and was getting my reward. I was winning the game.

In his 2013 documentary on video games that changed the world, Charlie Brooker, who knows so much about these things, caused a small stir when he suggested that Twitter was in essence, an online multiplayer game. Considering how high-mindedly people like me talk about social media as platforms for change, tools of democratisation and so on, it’s a provocative view to take. But Brooker is right. Twitter users are engaged in a massive game, possibly without end. We measure the success of individual moves (tweets) with retweets and favourites: keep pulling off these successful moves, and we can see our scores go up, in terms of followers accumulated. Not counting the uber famous, who will get a million retweets for the most grudgingly given “I HEART MY FANS; here’s the merchandise page” tweet, most of us are in this game to some extent.

But the description of Twitter as a game has one problem: Twitter can have real-life consequences.

Periodically (well, every time Grand Theft Auto comes out), Keith Vaz or Susan Greenfield or someone will get terribly upset about the ruination caused to young minds or young morals by all this mindless violence. This game lets you steal cars! Run down old ladies! All sorts of unspeakable things! But GTA and other games let you do nothing of the sort: at best, they let you pretend you’re doing these things. In fact, it’s not even that: it lets you control a character, whose character is already somewhat predetermined, in doing some of these things. You’re essentially engaged in a technologically advanced form of improv theatre. Except far more entertaining.

And this is where the Twitter-as-game thing falters: if I threaten to blow up a plane while playing a normal video game, nothing will happen to me. If I do it on Twitter, well…

Last Sunday a 14-year-old Dutch girl called Sarah got in trouble for tweeting that she was a member of Al Qaeda and was about to do “something big” to an American Airlines flight.

According to Dutch news agency BNO, the exchange went as follows:

“Hello my name’s Ibrahim and I’m from Afghanistan. I’m part of Al Qaida and on June 1st I’m gonna do something really big bye,” the girl, identifying herself only as Sarah, said in Sunday’s tweet. Soon after, American Airlines responded in their own tweet: “Sarah, we take these threats very seriously. Your IP address and details will be forwarded to security and the FBI.”

“omfg I was kidding. … I’m so sorry I’m scared now … I was joking and it was my friend not me, take her IP address not mine. … I was kidding pls don’t I’m just a girl pls … and I’m not from Afghanistan,” the girl said in subsequent tweets, later adding: “I’m just a fangirl pls I don’t have evil thoughts and plus I’m a white girl.”

It’s a stupid thing to do, obviously. But Sarah was playing by the rules of the game. She was being provocative, and, in her mind at least, funny. These are things that get you RTs and followers.

But sadly for Sarah, and the rest of us, there comes a point where social media stops being a game and starts being serious business.

We’ve seen this in the UK, of course, with Paul Chambers and the infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

That entire case was a travesty, because no one at any point believed Chambers even meant to behave threateningly. It’s unlikely anyone really believes Sarah meant anything by her tweet either, but in the order of things so far established, directing a comment at an account (at-ing someone, for want of a better phrase), as the Dutch girl did, is worse than simply referring to them, as Chambers did in his tweet about blowing Doncaster’s Robin Hood airport “sky high”.

Where is all this going to end up? I really don’t know. But I can only reiterate the point made many times before that, intriguingly, with the increasing ease of free speech, we’re seeing the rise of an increasing urge to censor; not just in authorities, but in everyday people.

It’s an urge we have to resist.

This article was originally published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Dec 2013 | News and features

2013 in the UK was the year social media became a “how” rather than a “why” issue. We’re no longer explaining what people do on the web, now we’re discussing how we behave. And we talked most about the abuse and threats received by many women on Twitter. When writer Caitlin Moran proposed a one-day Twitter boycott in August, Index’s Padraig Reidy responded. Read here

Communal censorship reared its ugly head in the UK when Madras Cafe, a Bollywood action film, was withdrawn from cinemas after protesters claimed it was anti-Tamil. Salil Tripathi likened the incident to the rows over Gurpreet Khaur Bhatti’s Bezhti and Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses

When Guardian columnist Suzanne Moore found herself at the centre of a storm after an article in which she described the idealised body shape of a “Brazilian transexual”, the Observer took the entirely sensible decision to commission Moore’s old friend Julie Burchill to defend her. The effect was described neatly by tweeter Stuart Houghton: “Julie Burchill has poured oil to calm troubled waters. Then drowned some seabirds in the oil. Then set fire to the oil.”

Index on Censorship refrained from getting involved. Until a government minister did…

Oh, Internet (there was a free speech point to this, honest)

As protesters filled Istanbul’s Gezi Park this summer, Ece Temelkuran explained the Turkish government’s fear of the social media generation.

2 Aug 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Writer Caitlin Moran (Image Demotix/Ken Jack)

Times columnist Caitlin Moran’s blog post on Twitter, threats and free speech this morning has gone viral. As I type, the page has crashed due to traffic overload, and apparently taken the entire Random House website with it.

The past week, online at least, has been dominated by discussions of misogynist abuse and threats on Twitter. I’m fighting a losing battle here in trying not to refer to this behaviour as “trolling”, but I think it’s still important to call abuse and threats what they are, rather than giving them a whole new category because they occur online. Calling it “trolling” undermines both trolling itself, in some ways a noble tradition, and what’s actually happening, which is women being threatened with rape by strangers.

Moran explains the exhausting and scary feeling of being attacked on Twitter, and the despair of being told that nothing can be done about it.

She goes on to quote Telegraph tech blogger Mic Wright, who earlier this week suggested that “This isn’t a technology issue – this is a societal issue”, suggesting he was simply dismissive of the idea that something should be done about misogyny online. Mic’s a friend, and a thoughtful writer. I don’t think he’s nearly as off-hand as Moran suggests, but I’ll leave it to you to read what he actually wrote. (While you’re at the Telegraph site, read Marta Cooper’s excellent piece as well)

Moran suggests “a fairly infallible rule: that anyone who says ‘Hey, guys – what about freedom of speech!’ hasn’t the faintest idea what ‘freedom of speech’ actually means.”

This, I’m afraid, is where it gets personal. As someone who may as well change his name by deed poll to “Hey, guys – what about freedom of speech!”, I can’t help feel Moran’s talking about me. And I think I’ve been a bit more considered, even while shouting about free speech.

Moran says:

“There is no such thing as ‘freedom of speech’ in this country. Since 1998, we’ve had Article 10 of the European Convention on “freedom of expression”, but that still outlaws – amongst many things – obscenity, sedition, glorifying terrorism, incitement of racial hatred, sending articles which are indecent or grossly offensive with an intent to cause anxiety or distress, and threatening, abusive or insulting words like to cause harassment, alarm or distress.”

Well, kind of. Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights says this:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

(Part 2 is kind of depressing, isn’t it?)

What Moran categorises as being outlawed by Article 10 are in fact various other laws, most of which have been around in some form or other long before the 1998 Human Rights Act which established the ECHR in UK law. Laws such as the Communications Act and the Public Order Act which, Lord knows, have their problems, not least for social media users. Ask Paul Chambers.

Moran then says:

“As you can see, if you are suggesting that you are allowed to threaten someone on Twitter with rape or death under “freedom of speech”, then you do not – as predicted – have any idea what “freedom of speech” means. Because it’s prosecutable.”

Two things: One, I’m not sure anyone really has been shouting “free speech for rape threats”. Two, it is possible to shout “freedom of speech” even when things are prosecutable. In fact, it’s what free speech campaigners such as Index, English PEN and Article 19 spend most of our time doing. All governments protect free speech “within the law”. Usually, the law is the problem, as we’ve seen with issues from England’s libel laws right up to Russia’s brand new anti “gay propaganda” law.

Moran identifies a certain cynicism in people who say abuse and threats are simply part and parcel of the web (“NOTHING CAN CHANGE. THE INTERNET JUST IS WHAT IT IS!”) saying what they really mean is that they don’t want things to change.

This strand certainly exists. The old-style keyboard warrior who thinks the web is strictly for arguing and not cat videos and getting strangers to help you with the crossword, or generally doing nice things and learning more about other people and places. The internet, for them is SERIOUS BUSINESS, and girls and pansies who can’t take the heat should get out of the kitchen. Or go back to the kitchen. Definitely something about kitchens.

But there is also a good reason to be wary, or at least hesitant, about calls for changing the web. A lot of time spent defending free speech is not actually about defending what people say, but defending the space in which they can say it (I’ll refrain from misquoting Voltaire here). It may be idealistic, but we genuinely believe that given the space and the opportunity to discuss ideas openly, without fear of retribution, we’ll figure out how to do things better. Censorship holds society back. In fact, it’s the litmus test of a society being held back.

When the cry goes up that “something must be done”, it’s normally exactly the right time to put the brakes on and think very hard about what we actually want to happen. The web is wonderful, and possibly the greatest manifestation of the free speech space we’ve ever had, but it’s also susceptible to control. Governments such as those in China and Iran spend massive resources on controlling the web, and do quite a good job of it. Other states simply slow the connection, making the web a frustrating rather than liberating experience. Some governments simply pull the plug. The whole of YouTube has been blocked in Pakistan for almost a year now, because something had to be done about blasphemous videos. Last month David Cameron announced his plans to take all the bad things away, after the Daily Mail ran a classic something-must-be-done campaign against online porn.

There are, as Moran rightly points out, laws against threatening people with rape. Perhaps the police and the CPS should take these threats more seriously (I only say “perhaps” because I don’t know exactly what the various police forces have been doing about the various threats in the past week, not because I think it’s arguable that the police and CPS should take rape threats less seriously), but I’m wary of demanding more action on things that are already illegal. Some of the proposed Twitter fixes are interesting, but their implications need to be thought through, particularly how they could be used against people we like as well as people we don’t like.

After outlining her support for a boycott of Twitter on Sunday 4 August, Moran concludes:

“The main compass to steer by, as this whole thing rages on, doubtless for some months to come, is this: to maintain the spirit that the internet was conceived and born in – one of absolute optimism that the future will be better than the past. And that the future will be better than the past because internet is the best shot we’ve had yet for billions of people to communicate equally, and peacefully, and with the additional ability to post pictures of thatched houses that look ‘surprised.’”

On this, I agree absolutely. In fact, I pretty much wrote the same thing last week:

The current debate in the UK portrays the web overwhelmingly as the habitat of trolls, predators, bullies and pornmongers. And that, plus the police are watching too, ready to arrest you for saying the wrong thing.

I can’t help feeling that all this doom-mongering could be self fulfilling. If we keep thinking of the web as the badlands, that’s how it will be, like a child beset by endless criticism and low expectations. We need to talk more about the positive side of life online – the conversations, the friendships, the opportunities – if we’re going to get the most out of it.

We do need to protect and promote the good parts of life online. But we should be very careful of the idea that we can simply block out the negative aspects without having a knock-on effect. We’re in uncharted territory. The wrong turn could be very, very costly.