In Turkey, a loud disagreement finds a common ground: Journalism is not a crime

44 journalists are in Turkey’s jails tonight. We demand their release. Because we, too, are journalists, and… pic.twitter.com/jzDsd9MOqm

— P24 (@P24Punto24) July 11, 2016

The above was part of a series of tweets were sent out by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24) near midnight on 11 July. P24 joined editors, reporters, columnists, bloggers and civil society activists, who are, despite being a minority in the shackled media sector in Turkey, determined to defend the honour of our noble profession till the very end.

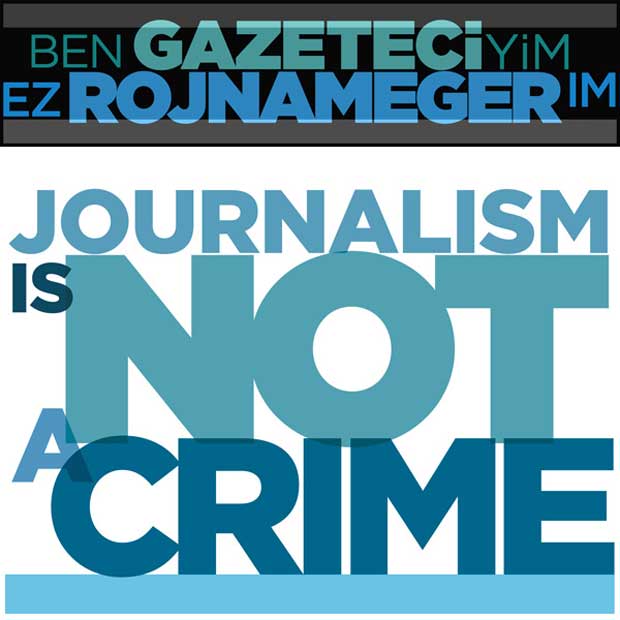

The “Journalism is not a crime” logo is now in circulation in Turkish, Kurdish, English and a variety of other languages. The hope is that this slogan will trigger widespread domestic and international solidarity to rescue Turkey’s journalism from being turned into a total wreck.

On Tuesday morning, I watched three of the figures behind the campaign on TV. It is a rarity, these days, that any voice in defence of freedoms and rights find a public space on Turkey’s TV stations. It filled me with a sense of pride, hope and courage, but was tinged with a slight sense of despair.

That any so-called private mainstream TV channel would invite them on to share their views is a daredevil act, because these newsrooms are practically run by the same proprietors and their puppet editors, whose variety of businesses are strictly dependent on the public contracts, and any challenge to the AKP government would mean severe punishment. This is the impact self-censorship, in addition to direct censorship, has had on public debate as well as free reporting in roughly 90% of the Turkish media.

The appearance of Fehim Işık, a Kurdish columnist, Said Sefa, owner of the independent news site Haberdar, and Arzu Demir, a leading figure in the Turkish Journalists’ Union on the tiny Can Erzincan TV took place with an air of gloom. One of the three or four channels still willing to broadcast critical and diverse content, this channel will be dropped fromTurksat satellite by 20 July, on the back of a murky decision by the satellite board over claims it spreads terrorist propaganda.

Experienced lawyers are flabbergasted once more by the lawlessness reigning over the media domain, but there is little they can do about it. A month or so ago, another TV channel, IMC TV, met the same fate and was forced to switch to a different satellite service, losing more than 75% of its mainly Kurdish audience. Can Erzincan TV, a financially strapped and tiny liberal outlet, will also lose viewers. This is a cunning form of censorship by the authorities.

With Can Erzincan TV pushed out of the limelight, Turkish viewers will be left only with Halk TV and FoxTV, both of which are also in the crosshairs for further punitive actions.

When – rather than if – they also are gone, the AKP will have a free ride on the most powerful, efficient medium in journalism. Remnant portions of dignified journalists, regardless of their political colour, will have to retreat into a handful newspapers and news sites.

This is the bad news.

The good news is that, as I expected, the very core of real journalism in Turkey is intent on professional resistance to further erosion. The current initiative #Iamajournalist is yet another amazing attempt to rise up. I watched it develop spontaneously as a social media movement, which rapidly turned into a community action.

The very good news is that it now contains elements which find common cause between the liberals, leftists, Kurds, seculars, and concerned conservatives: protecting journalism as the main pillar of democracy. This is unfinished business in Turkey, and something the country’s “dark forces” want to reverse in full.

For a week starting from July 11, a handful of newspapers, websites and TV channels will display the “Journalism is not a crime” logo. Social media, too, is busy.

“Protecting freedom of press also means defending the public’s right of access to information. In a society where the right to information is restricted, one cannot speak of democracy,” they say.

“As journalists we will do everything within our power to be the voice of those who have been marginalised, imprisoned, and silenced for doing their jobs and defending the freedom of press and freedom of access to information for all of us.”

We must now keep in our minds the 44 journalists in Turkish jails. It’s a grim number that will rise. There are thousands of journalists who are forced to operate in newsrooms resembling labor camps, or — to use a term I used in my Harvard paper a year and a half ago – “open-air prisons”, subordinated to spread propaganda, lies and hate speech.

This spontaneous initiative, which grew without the involvement of some polarised journalist organisations, needs attention, and support. Journalists in Turkey are tough nuts, but the conditions are swiftly hardening. We need to keep the spirit of journalism alive.