22 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Statements

The European Commission (EC) on Thursday released a “mythbuster” on the controversial Court of Justice of the European Union ruling on the “right to be forgotten”. The document tackles six perceived myths surrounding the decision by the court in May to force all search engines to delink material at the request of internet users — that is, to allow individuals to ask the likes of Google and Yahoo to remove certain links from search results of their names. Many — including Index on Censorship — are worried about the implications of the right to be forgotten on free expression and internet freedom, which is what the EC are trying to address with this document. But after going through the points raised, it is clear they need some of their own mythbusting.

1) Groups like Index on Censorship have not suggested “the judgement does nothing for citizens”. We believe personal privacy on the internet does need greater safeguards. But this poor ruling is a blunt, unaccountable instrument to tackle what could be legitimate grievances about content posted online. As Index stated in May, “the court’s ruling fails to offer sufficient checks and balances to ensure that a desire to alter search requests so that they reflect a more ‘accurate’ profile does not simply become a mechanism for censorship and whitewashing of history.” So while the judgement does indeed do something for some citizens, the fact that it leaves the decisions in the hands of search engines – with no clear or standardised guidance about what content to remove – means this measure fails to protect all citizens.

2) The problem is not that content will be deleted, but that content — none of it deemed so unlawful or inaccurate that it should be taken down altogether — will be much harder, and in come cases, almost impossible to find. As the OSCE Representative on Media Freedom has said: “If excessive burdens and restrictions are imposed on intermediaries and content providers the risk of soft or self-censorship immediately appears. Undue restrictions on media and journalistic activities are unacceptable regardless of distribution platforms and technologies.”

3) The EC claims the right to be forgotten “will always need to be balanced against *other* fundamental rights” — despite the fact that as late as 2013, the EU advocate general found that there was no right to be forgotten. The mythbuster document also states that search engines must make decisions on a “case-by-case basis”, and that the judgement does not give an “all clear” to remove search results. The ruling, however, is simply inadequate in addressing these points. Search engines have not been given any guidelines on delinking, and are making the rules up as they go along. Search engines, currently unaccountable to the wider public, are given the power to decide whether something is in the public interest. Not to mention the fact that the EC is also suggesting that sites, including national news outlets, should not be told when one of their articles or pages have been delinked. The ruling pits privacy against free expression, and the former is trumping the latter.

4) By declaring that the right to be forgotten does not allow governments to decide what can and cannot be online, the mythbuster implies that governments are the only ones who engage in censorship. This is not the case — individuals, companies (including internet companies), civil society and more can all act as censors. And while the EC claims that search engines will work under national data protection authorities, these groups have yet to provide guidelines to Google and others. The mythbuster itself states that a group of independent European data protection agencies will “soon provide a comprehensive set of guidelines” — the operative word being “soon”. This group — known as the Article 29 Working Party — is the one suggesting you should not be informed when your page has been delinked. And while it may be true that “national courts have the final say” when someone appeals a decision by a search engine to *decline* a right to be forgotten request, this is not necessarily the case the other way around. How can you appeal something you don’t know has taken place? And what would be the mechanism for you to appeal?

As of 1 Sept, Google alone has received 120,000 requests that affect 457,000 internet addresses and may remove the information without guidance, at their own discretion and with very little accountability. To argue that this situation doesn’t allow for at least some possibility of censorship, seems like a naive position to take.

5) All decisions about internet governance will to an extent have an impact on how the internet works, so it is important that we get those decisions right. In its current form, the right to be forgotten is not up to the job of protecting internet freedom, free expression and access to information.

6) It may not render data protection reform redundant, but we certainly hope the reform takes into account concerns raised by free expression groups on the implementation of, and guidelines surrounding, the right to be forgotten ruling.

This article was posted on 22 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jul 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, United Kingdom

The British House of Lords has slammed the recent “right to be forgotten” ruling by the court of justice of the European Union, deeming it “unworkable” and “wrong in principle”.

The Lords’ Home Affairs, Health and Education EU Sub-Committee stated in a report on the ruling, published Wednesday, that: “It ignores the effect on smaller search engines which, unlike Google, may not have the resources to consider individually large numbers of requests for the deletion of links.”

The committee added that: “It is wrong in principle to leave to search engines the task of deciding many thousands of individual cases against criteria as vague as ‘particular reasons, such as the role played by the data subject in public life’. We emphasise again the likelihood that different search engines would come to different and conflicting conclusions on a request for deletion of links.”

The ruling from May this year forces search engines, like Google, to remove links to articles found to be outdated or irrelevant at the request of individuals, even if the information in them is true and factual and without the original source material being altered. Following this, Google introduced a removal form which received some 70,000 requests within two months.

The Lords committee recommends, among other things, that the “government should persevere in their stated intention of ensuring that the Regulation no longer includes any provision on the lines of the Commission’s ‘right to be forgotten'”.

Index on Censorship has repeatedly spoken out against the ruling, stating that it “violates the fundamental principles of freedom of expression“, is “a retrograde move that misunderstands the role and responsibility of search engines and the wider internet” and “a blunt instrument ruling that opens the door for widespread censorship and the whitewashing of the past”.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jun 2014 | Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features

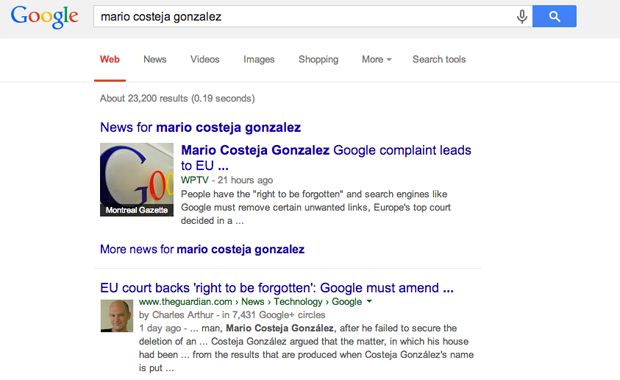

On May 13, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held in Google Spain v AEPD and Mario Costeja González that there was a “right to be forgotten” in the context of data processing on internet search engines. The case had been brought by a Spanish man, Mario Gonzáles, after his failure to remove an auction notice of his repossessed home from 1998, available on La Vanguardia, a widely-read newspaper website in Catalonia.

The CJEU considered the application of various sections of Article 14 of EU Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 24, 1995 covering the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data.

A very specific philosophy underlines the directive. For one, it is the belief that data systems are human productions, created by humans for humans. In the preamble to Article 1 of Directive 95/46, “data processing systems are designed to serve man; … they must, whatever the nationality or residence of natural persons, respect their fundamental rights and freedoms notably the right to privacy, and contribute to … the well-being of individuals.”

Google Spain and Google Inc.’s argument was that such search engines “cannot be regarded as processing the data which appear on third parties’ web pages displayed in the list of search results”. The information is processed without “effecting the selection between personal data and other information.” Gonzáles, and several governments, disagreed, arguing that the search engine was the “controller” regarding data processing. The Court accepted the argument.

Attempts to distinguish the entities (Google Inc. and Google Spain) also failed. Google Inc. might well have operated in a third state, but Google Spain operated in a Member State. To exonerate the former would render Directive 95/46 toothless.

The other side of the coin, and one Google is wanting to stress, is that such a ruling is a gift to the forces of oppression. A statement from a Google spokesman noted how, “The court’s ruling requires Google to make difficult judgments about an individual’s right to be forgotten and the public’s right to know.”

Google’s Larry Page seemingly confuses the necessity of privacy with the transparency (or opacity) of power. “It will be used by other governments that aren’t as forward and progressive as Europe to do bad things. Other people are going to pile on, probably… for reasons most Europeans would find negative.” Such a view ignores that individuals, not governments, have the right to be forgotten. His pertinent point lies in how that right might well be interpreted, be it by companies or supervisory authorities. That remains the vast fly in the ointment.

Despite his evident frustrations, Page admitted that Google had misread the EU smoke signals, having been less involved in matters of privacy, and more committed to a near dogmatic stance on total, uninhibited transparency. “That’s one of the things we’ve taken from this, that we’re starting the process of really going an talking to people.”

A sense of proportion is needed here. The impetus on the part of powerful agencies or entities to make data available is greater in the name of transparency than private individuals who prefer to leave few traces to inquisitive searchers. Much of this lies in the entrusting of power – those who hold it should be visible; those who have none are entitled to be invisible. This invariably comes with its implications for the information-hungry generation that Google has tapped into.

The critics, including those charged with advising Google on how best to implement the EU Court ruling, have worries about the routes of accessibility. Information ethics theorist Luciano Floridi, one such specially charged advisor, argues that the decision spells the end of freely available information. The decision “raised the bar so high that the old rules of Internet no longer apply.”

For Floridi, the EU Court ruling might actually allow companies to determine the nature of what is accessible. “People would be screaming if a powerful company suddenly decided what information could be seen by what people, when and where.” Private companies, in other words, had to be the judges of the public interest, an unduly broad vesting of power. The result, for Floridi, will be a proliferation of “reputation management companies” engaged in targeting compromising information.

Specialist on data law, Christopher Kuner, suggests that the Court has shown a lack of concern for the territorial application, and implications, of the judgment. It “fails to take into account the global nature of the internet.” Wikipedia’s founder, Jimmy Wales, also on Google’s advisory board, has fears that Wikipedia articles are set for the censor’s modifying chop. “When will a European court demand that Wikipedia censor an article with truthful information because an individual doesn’t like it?”

The Court was by no means oblivious to these concerns. A “fair balance should be sought in particular between that interest [in having access to information] and the data subject’s fundamental rights under Articles 7 [covering no punishment without law] and 8 [covering privacy] of the Charter.” Whether there could be a justifiable infringement of the data subject’s right to private information would depend on the public interest in accessing that information, and “the role played by the data subject in private life.”

To that end, Google’s service of removal is only available to European citizens. Its completeness remains to be tested. Applicants are entitled to seek removal for such grounds as material that is “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant, or excessive in relation to the purposes for which they were processed.”

An explanation must accompany the application, including digital copies of photo identification, indicating that ever delicate dance between free access and anonymity. For Google, as if it were an unusual illness, one has to justify the assertion of anonymity and invisibility on the world’s most powerful search engine.

Others have showed far more enthusiasm. Google’s implemented program received 12,000 submissions in its first day, with about 1,500 coming from the UK alone. Floridi may well be right – the age of open access is over. The question on who limits that access to information in the context of a search, and what it produces, continues to loom large. The right to know jousts with the entitlement to be invisible.

This article was published on June 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Both Google and the European Union are funders of Index on Censorship

21 May 2014 | Counterpoint, Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features

Enshrining the right to be forgotten is a further step towards allowing individuals to take control of their own data, or even monetise it themselves, as we proposed in the Project 2020 white paper (Scenarios for the Future of Cybercrime). The way the law stands in the EU currently, we have legal definitions for a data controller, a data processor and a data subject, an oddity, which lands each of us in the bizarre situation where we are subjects of our own data rather being able to assert any notion of ownership over it. With data ownership comes the right to grant or deny access to that data and to be responsible for its accuracy and integrity.

In response to the ECJ judgement, I have seen a lot of commentators cry “censorship” and make all kinds of unsupportable comparisons with book burning (or pulping), these reactions are misguided and out of all proportion to the decision made. Let’s remember what has been decreed is that an individual has the right to request that certain information be de-indexed from search and aggregation engines. That request is not an order and each one must go through due process and consideration before any changes are made, including if necessary consideration by a court of law. Individuals are not being granted the right to rewrite history, they are being given the right to request, within the strictures of the law, that certain publishers cease to publish information about them which they consider deleterious. They are being given the right to be able to manage their own image online, it seems bizarre that this right is seen by some as the repression of free speech when in effect it gives the individual the right to speak up about something which they find personally damaging.

In 2009, an organisation called “The Consulting Association” was found to be operating a commercial blacklist service to the construction industry. This organisation held detailed files on construction professionals, listing their names, family relationships, newspaper cuttings and details of criminal records. Several global construction companies paid for access to this data and over 3000 individuals were potentially prevented from gaining employment in their industry. Of course this shocks us, and rightly the Information Commissioner took action, seizing the data in question and informing those affected. In many ways a search engine’s constant aggregation of data and even more its contextualisation and publication of that data as relevant to a given name fulfils the same function, now you have a right to at least influence it, even if you cannot stop it.

The ruling is the right one. The court recognises that information that was “legally published” remains so and that the individual has no right to censor it. However, they also recognise that search engines collect, retrieve, record, organise, store and disclose information on an on-going basis and that this constitutes “processing” of data under the EU directive. Further, given that the search engine determines the means and purpose of their own data processing, they are also a “Data Controller” under that directive and again must fulfil the legal requirements of such an entity; any other court decision would weaken that whole directive beyond repair. The entirety of information turned up in response to a search on a person’s name, represents a whole new level of publishing and the discrete items of information would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to put together in the absence of a search engine.

While there will of course be technical and procedural issues that arise from this ruling and there will doubtless be individuals seeking to evade public scrutiny, any other decision on this would have simply blown away the EU Data Protection directive and that is not something any us should be advocating. Consider the wider ramifications of this decision, if a search engine is now a “Data Controller” in the eyes of the law, shouldn’t they be notifying us whenever they collect information about us? Would it be a breath of fresh air if you could begin to understand the wealth of information out there about you and begin to realise an income from it yourself? Personal information is a commodity that commands a financial premium and right now it is others who realise those gains. It’s time we advocated for real ownership of our own data.

Before personal data became a commodity mined by corporations and attackers alike, the need for a legal stance on the identity of the “owner” of data relating to oneself may have seemed laughable. However that has landed us in the situation of today when entities that mine and monetise that same data can refer to this very welcome EU ruling as “disappointing”. Commercially disappointing it may be, however it is a step, albeit a small one, in the right direction.

This article was originally posted on May 13, 2014 at countermeasures.trendmicro.eu