17 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

I was retweeted by Caitlin Moran on Wednesday evening (#humblebrag). It was a curious glimpse into the world of internet fame. Suddenly my replies were full of retweets and favourites – hundreds of them.

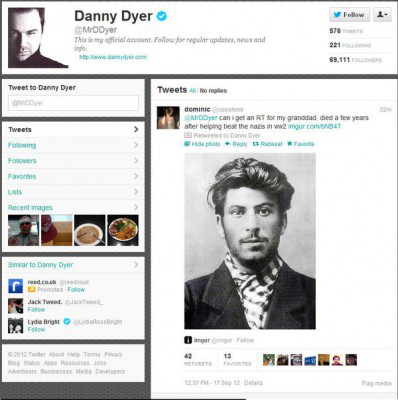

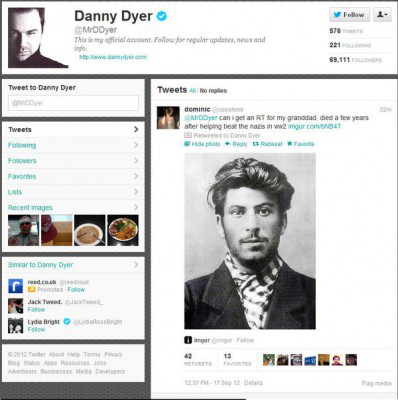

The tweet itself was fairly innocuous; in fact, it was a bit of a cheat. I’d copied someone else’s tweet, adding my own disbelief. And that tweet by someone else was a retweet of a three-year old tweet by well-hard actor Danny Dyer, who had been tricked, quite amusingly, by someone asking for a shout out to his grandad who had helped beat the Nazis, accompanied by a picture of a young Stalin. I’d missed it at the time.

Anyway, on it came throughout the evening, retweets, favourites, questions, statements of the obvious, snark…. It was weird, and unexpected, and kind of exciting. It was like I’d done something really good, rather than just stealing someone else’s old joke. And I was able to track exactly how good it was. I had pulled some kind of killer move and was getting my reward. I was winning the game.

In his 2013 documentary on video games that changed the world, Charlie Brooker, who knows so much about these things, caused a small stir when he suggested that Twitter was in essence, an online multiplayer game. Considering how high-mindedly people like me talk about social media as platforms for change, tools of democratisation and so on, it’s a provocative view to take. But Brooker is right. Twitter users are engaged in a massive game, possibly without end. We measure the success of individual moves (tweets) with retweets and favourites: keep pulling off these successful moves, and we can see our scores go up, in terms of followers accumulated. Not counting the uber famous, who will get a million retweets for the most grudgingly given “I HEART MY FANS; here’s the merchandise page” tweet, most of us are in this game to some extent.

But the description of Twitter as a game has one problem: Twitter can have real-life consequences.

Periodically (well, every time Grand Theft Auto comes out), Keith Vaz or Susan Greenfield or someone will get terribly upset about the ruination caused to young minds or young morals by all this mindless violence. This game lets you steal cars! Run down old ladies! All sorts of unspeakable things! But GTA and other games let you do nothing of the sort: at best, they let you pretend you’re doing these things. In fact, it’s not even that: it lets you control a character, whose character is already somewhat predetermined, in doing some of these things. You’re essentially engaged in a technologically advanced form of improv theatre. Except far more entertaining.

And this is where the Twitter-as-game thing falters: if I threaten to blow up a plane while playing a normal video game, nothing will happen to me. If I do it on Twitter, well…

Last Sunday a 14-year-old Dutch girl called Sarah got in trouble for tweeting that she was a member of Al Qaeda and was about to do “something big” to an American Airlines flight.

According to Dutch news agency BNO, the exchange went as follows:

“Hello my name’s Ibrahim and I’m from Afghanistan. I’m part of Al Qaida and on June 1st I’m gonna do something really big bye,” the girl, identifying herself only as Sarah, said in Sunday’s tweet. Soon after, American Airlines responded in their own tweet: “Sarah, we take these threats very seriously. Your IP address and details will be forwarded to security and the FBI.”

“omfg I was kidding. … I’m so sorry I’m scared now … I was joking and it was my friend not me, take her IP address not mine. … I was kidding pls don’t I’m just a girl pls … and I’m not from Afghanistan,” the girl said in subsequent tweets, later adding: “I’m just a fangirl pls I don’t have evil thoughts and plus I’m a white girl.”

It’s a stupid thing to do, obviously. But Sarah was playing by the rules of the game. She was being provocative, and, in her mind at least, funny. These are things that get you RTs and followers.

But sadly for Sarah, and the rest of us, there comes a point where social media stops being a game and starts being serious business.

We’ve seen this in the UK, of course, with Paul Chambers and the infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

That entire case was a travesty, because no one at any point believed Chambers even meant to behave threateningly. It’s unlikely anyone really believes Sarah meant anything by her tweet either, but in the order of things so far established, directing a comment at an account (at-ing someone, for want of a better phrase), as the Dutch girl did, is worse than simply referring to them, as Chambers did in his tweet about blowing Doncaster’s Robin Hood airport “sky high”.

Where is all this going to end up? I really don’t know. But I can only reiterate the point made many times before that, intriguingly, with the increasing ease of free speech, we’re seeing the rise of an increasing urge to censor; not just in authorities, but in everyday people.

It’s an urge we have to resist.

This article was originally published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Apr 2014 | Bangladesh, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Reports, News

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Bangladesh witnessed the internet take on an increasing role in its socio-political sphere in 2013. Usage trends swung more toward heart-warming positives, in contrast to the country’s regulatory precedents, which despite policymakers facilitating net use via cheaper connections and better infrastructure, have been mostly negative. Common people felt empowered using the internet.

Last February, tens of thousands of people were gathered, inspired by blog posts and social media to protest for the first time in the country’s history. At the same time, religious zealots started attacking online activists, and policymakers initiated the use of a draconian ICT (information and communication technology) act to clamp down on opposition, thus threatening digital freedom of expression overall.

Internet usage, mobile telephony penetration, and other ICT-enabled applications have been enjoying steady growth in both Bangladesh’s private and public sectors for over a decade. The present political leadership came to power with a mandate to “digitise” the country by implementing its Digital Bangladesh by 2021 vision. This policy rolled out net enabled ICT centers to ensure easier access of information for its citizens all over Bangladesh. At present, the national teledensity is at over 70%. Around 20% of the population use the internet, of which 90% go online using mobile phone services. There are around 200,000 local bloggers based in Bangladesh, who alongside millions of Bangladeshi Facebook users were until recently enjoying near-uninhibited freedom to express their thoughts online.

The true power of social media to mobilise massive groups of people on a political issue was first observed in Bangladesh during the Shahbag movement in February 2013. Like the 2011 uprising in Egypt’s Tahrir Square, protesters gathered for several weeks in the Shahbag intersection of Dhaka University campus, demanding justice against known war criminals of its liberation war in 1971. This movement was initiated by local bloggers and social network users, and flourished with their help. People were using online media freely to organise in the real world and to create spaces for net based dialogue on critical issues. However, along with such freedom came confrontation. Shahbag made public the conflict between the ultra religious, anti-establishment elements and the moderate, mainstream and secular netizens. One pro-Shahbag blogger was killed, many other online activists were threatened with physically harm by the zealots. Suddenly an online inspired mass protest, which was enjoying complete freedom of expression in the digital space, turned out to be the root cause of a messy and prolonged offline affair.

The Shahbag movement exposed the major weaknesses of the local legal system, responsible for guaranteeing its citizens’ freedom of expression. The government turned out to be confused in their decision making process and tried to appease both sides. It first banned several ultra-religious sites. Then the law enforcement agency arrested four secular Shahbag bloggers and organisers, charging them with “harming religious sentiments”. Such actions sent out confusing signals to the general population and posed serious questions on the existence of any tangible legal safety net for online communication in Bangladesh.

In fact, the government’s performance in the digital space has been consistently disappointing between 2012 and 2013. In addition to its self-conflicting stance on Shahbag, it applied a heavy-handed approach in dealing with other web services throughout the year. YouTube was banned for months (September 2012 to May 2013) due to The Innocence of Muslims, which ignited major protests in Bangladesh. Additionally, Facebook was blocked on several occasions, from periods of a few hours to days at a stretch. Freedom House included Bangladesh for the first time in its yearly Freedom On the Net report in 2013. Based on its performance in 2012 and first half of 2013, the internet in Bangladesh was found to be partially free, enjoying a relatively better online environment in comparison with its South Asian peers, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Nevertheless the situation is getting worse. Indiscriminate applications of the ICT Act 2006, a rise of online hate speech and related crimes have left net users in Bangladesh insecure.

In 2013, the government started using the ICT Act of 2006 more frequently, mainly to address issues related to online space and freedom of expression. This act was formulated in early 2000 and according to many legal experts, it was due to be amended to become more user-friendly and inclusive. The Bangladeshi government did amend it in August 2013, but unfortunately made it more repressive and inflexible. The newly amended act provisions a maximum 10 years in prison and fines up to £74,555 for any offensive religious, social, or political expression made online. It moreover made arrests under this act non-bailable and the police were given the power to arrest people without a warrant. Instead of strengthening the legal system to protect peoples’ right to communicate freely online, this act tightened its grip on peoples’ freedom of communication. A series of arrests took place and several court cases were filed under the act in 2013. Besides the bloggers, editors and journalists of two newspapers, two NGO officials, and several other people were arrested, some of whom are close to opposition party politics. One university teacher was sentenced to seven years in prison under the act for threatening to kill the prime minister through a Facebook status.

Overall, the present state of affair of net freedom in Bangladesh is very uncertain. There has been no independent regulatory or legal body put in place to protect the rights of the people online. Civil society needs to be more active to thwart any digital policing that compromises public freedom. As the challenges related to ICT access in Bangladesh are being solved fast, it is now high time to make sure that its citizens enjoy true freedom while using such digital infrastructure.

This article was posted on 10 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Mar 2014 | Digital Freedom, Events

(Image: Shutterstock)

Index on Censorship, in association with Doughty Street Chambers, invites you to attend our high-level panel discussion asking who runs the internet?

At a moment when the revelations on NSA and GCHQ mass surveillance are opening up a wide debate about our digital freedoms, our panel will discuss how free the net is today, and the main challenges that lie ahead. In the next couple of years, major international summits will debate new rules on internet governance, and whether to adopt a top-down approach as favoured by China and Russia, or maintain a more open, multistakeholder networked approach. Meanwhile, from the EU to Brazil, reactions to the Snowden’s revelations of mass snooping suggest there is a growing risk of fragmentation of the internet, with calls for forced local hosting of data.

We are delighted to be hosting speakers:

Bill Echikson – Head of Free Expression EMEA, Google

Richard Allan – Head of Europe, Middle East and Africa, Facebook

Tusha Mittal – formerly a correspondent for Tehelka and currently a Fellow at the Reuters Institute, Oxford University

Kirsty Hughes – CEO, Index on Censorship

The panel will make short introductory remarks ensuring plenty of time for a lively Q&A session.

The event will be held at Doughty Street Chambers (53-54 Doughty St, London WC1N 2LS) on Wednesday 2nd April 6-7.30pm, followed by a drinks reception. To RSVP please fill in your details here. If you have any questions please contact Fiona Bradley ([email protected]).