Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

After decades of dictatorship and two years of arguments and compromises, Tunisians passed a new constitution laying the foundations for a new democracy. (Photo: Mohamed Krit / Demotix)

“A model to other peoples seeking reform” said UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon on the successful passing in 2014 of the new Tunisian Constitution. Championing a secular political and legal system following the popular uprisings of 2011, this constitution sought to maintain robust protections of fundamental freedoms. However, the recent creation of the Technical Telecommunication Agency (ATT) threatens to undermine such progress and all in the service of digital surveillance.

Established by decree no. 2013-4506, bypassing parliamentary approval, ATT “provides technical support to judicial investigations into ICT-related crimes”, enabling it to monitor and record online traffic with full access to networks and information held by Internet Service Providers. Many critics of the agency liken it to the NSA; Tunisian Pirate Party member Raed Chammem stated on Twitter “We finally have our own Tunisian law-abusing agency…#NSA-like #A2T”.

The drafting process of the constitution demonstrated the core divergent forces at play in Tunisia. Central to this tension was the positioning of media freedom, most notably in the mandate and impartiality of the High Independent Authority for Audiovisual Communication (HAICA). Articles 122 and 124 reduced the authority to an advisory role as opposed to that of a regulator and required its membership to be elected by parliament. It took concerted lobbying by civil society activists and the National Union of Tunisian Journalists to modify both articles. As stated by Freedom House “the revised language is not just a victory for press freedom and the media sector, but also a triumph for Tunisia’s growing civil society.”

The fight for greater oversight by civil society and regulatory bodies as seen in the last minute amendments to the constitution has not, to date, impacted the creation and implementation of the ATT. The International Business Times wrote that the ATT “fails to properly define the organization’s relationship with judicial authorities, and there is no legal framework for providing civilian accountability”. They go on to quote Tunisian lawyer, Kais Berrjab who states that the ATT represents a “battery of legal irregularities related to unconstitutionality and illegality.”

With an emergent blogger-community, any movement to restrict, monitor or record online content, strikes at the heart of media freedom in Tunisia. Article five of decree no. 2013-4506 outlines that ATT activities will be “secret, unpublished and only sent to the government”. When coupled with the head of the agency being appointed by the Minister of Information and Communication alone, and government plans to exempt the ATT from legal obligations, which exist for all other agencies, in regards to transparency, the prominence of the state raises pertinent questions about the impartiality and non-partisanship of the agency.

The IB Times highlights a key motivation behind the creation of the ATT; the belief “that monitoring the activities of private citizens is essential to counterterrorism effort.” Indeed this argument is playing out across the world, most notably in the US concerning the actions of NSA and the UK with its own GCHQ.

Mounting public pressure to confront recent high-profile assassinations, as well as the perceived threat of Islamic extremism has been highlighted as key reasons for this move towards creating a more investigative body – ATT in all essences replaces the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) – however criticism remains as to how it can operate within the legal and political parameters outlined in the 2014 constitution.

In the same IB Times article, Jillian York of the Electronic Frontiers Foundation is quoted as saying, “starting with legitimate concerns about security, the state can then push beyond that and you see surveillance used against political dissidents or just in violation of basic privacy.” Herein lies the central conflict; the last minute redrafting of the constitution established civilian oversight, an impartial regulator and robust protections, but will the ATT, wired to the central government, through the Minister of Information and Communication, undermine such progress, making online participation as dangerous for journalists and bloggers as seen under the leadership of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali?

The passing of the constitution proved to be a powerful call-to-action for Tunisian civil society, reshaping the government’s relationship with the media and civil society and embedding freedom of media and expression at the core of the legal and political system. But with the establishment of the ATT, Tunisia risks damaging this precedent, undermining the progress, as part of an ill-defined counterterrorism campaign.

The constitution cannot exist outside any effort to counter terrorism; it should, in fact, lie at the core of these efforts. The combatting of militancy and terrorism requires the support and involvement of all sectors of society, including the media and civil society. But if it is the state that strikes the first blow against the ideals and optimism contained within the constitution, will the emergent civil society be able to defend it?

This article was posted on May 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

On the eve of World Press Freedom Day, Index on Censorship’s Melody Patry speaks to Al Jazeera about the threats to freedom of expression online.

(Image: Shutterstock)

Knowledge, claimed Francis Bacon, is power. It is also money. Which is why Canada’s newly drafted Digital Privacy Act, Bill S-4, is considered by the privacy fraternity to be a demon of some proportions. As Gillian Shaw of the Vancouver Sun (Apr 14) explains, “If you worry Big Brother is reporting everything you do on the Internet, changes introduced to Canada’s privacy legislation last week may prove your worries are not totally unfounded.”

The bill has striking similarities to proposed US legislation that proved so contentious it wound up in the deep freeze of US Congressional contemplation. The US Cyber Information Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA) would have granted blanket immunity to companies sharing user content with governments on the pretext of a pressing “cyber threat”. S-4, however, goes further, increasing the sharing of such user information with parties beyond government to private organisations.

The aim of such legislation is twofold: re-enforcing copyright barriers via the umbrella pretext of fighting crime and contractual infringement while eroding privacy protections. The snooping incentive in the case of Bill S-4 is considerable: to monitor those habits of downloading and use of material that just might breach intellectual property laws.

As with laws purportedly targeting digital piracy, it does more. University of Ottawa’s law professor, Michael Geist, has kept his eye on developments in the area of Canadian privacy law for some time. He is far from impressed by the latest measures on the part of the Canadian government. “Unpack the legalese and you find that organizations will be permitted to disclose personal information without consent (and without a court order) to any organization that is investigating a contractual breach or possible violation of any law” (Vancouver Sun, Apr 14).

Other effects follow on from S-4, read along with C-13 (the “cyber-bullying bill). Immunity to organisations disclosing subscriber or customer information to law enforcement authorities, or copyright trolls, will be granted. The mere fact that an investigation is taking place, be it into contractual breach, actual or potential, can trigger the need to disclose the confidential data of users of the service. Those users will not be informed of such disclosure, and organisations engaging in such acts will be under no obligation to do so.

One of the amending provisions states, for instance, that “an organization may collect personal information without the knowledge or consent of the individual only if it is reasonable to expect that the collection with the knowledge or consent of the individual would compromise the availability or the accuracy of the information and the collection is reasonable for purposes related to investigating a breach of an agreement or a contravention of the laws of Canada or a province.”

Geist makes various important points, noting how judicial management has been indispensable in keeping the information trawlers at bay. He cites the file sharing case of Voltage Pictures, a U.S. company which sought an order asking the internet service provider TekSavvy to disclose the names and addresses of thousands of users it claimed had infringed copyright. TekSavvy requested the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic to intervene for the purposes of informing the court over privacy and copyright trolling concerns.

The disclosure was granted by the federal court, but the move came with various safeguards with the intention of discouraging copyright trolling lawsuits. The point was considered fundamental by the court – compelling ISPs to reveal the private details of their subscribers would create a monumental strain on the court system. Many infringements would be of a non-commercial nature, and taking these to court would see a needless use of judicial resources. Even more significant, the cap of $5000 on liability for such non-commercial infringements “may be miniscule compared to the cost, time and effort in pursuing a claim against the subscriber.”

The court found Voltage’s conduct in seeking such disclosure potentially improper, though not sufficient to refuse the motion. Instead, the company was asked to guarantee that any subscriber information obtained would remain confidential, not be used for any other purposes, not be made public and not be disclosed to third parties. The fees for TekSavvy behind the disclosure would also be covered by Voltage.

The decision suggests heavy judicial oversight over the grants of such disclosure motions. Important safeguards include court involvement over the contents of the “demand letter” sent to subscribers. As Geist notes, the letter must include the message that “no Court has yet made a determination that such subscriber has infringed or is liable in any way for payment of damages.”

S-4 would make such protections redundant, stifling court scrutiny and enabling a ready disclosure of private user information between companies. In Geist’s words, “If Bill S-4 were the law, the court might never become involved in the case. Instead, Voltage could simply ask TekSavvy for the subscriber information, which could be legally disclosed (including details that go far beyond just name and address) without any court order and without informing their affected customer.”

The legislative moves on the part of the Canadian government reveal the addictive nature of such copyright legislation. Privacy is a subsidiary concern to the use of material provided by an ISP, while broadening the policing function against illegal use of information is paramount. The current Digital Privacy Act seems a less than distant echo of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Bill C-29. The government has evidently been there, but hasn’t yet done that.

Warrantless disclosure of private information is the holy grail of government regulation. The sacrificial lamb is always the privacy of citizens. This, goes the official drum roll, is necessary to protect the public. In truth, it is designed to protect corporate legal interests and pull down the walls of data protection.

This article was posted on 23 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

I was retweeted by Caitlin Moran on Wednesday evening (#humblebrag). It was a curious glimpse into the world of internet fame. Suddenly my replies were full of retweets and favourites – hundreds of them.

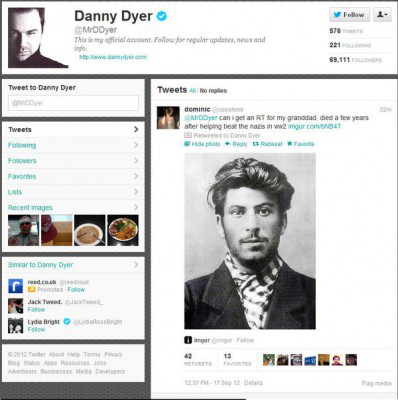

The tweet itself was fairly innocuous; in fact, it was a bit of a cheat. I’d copied someone else’s tweet, adding my own disbelief. And that tweet by someone else was a retweet of a three-year old tweet by well-hard actor Danny Dyer, who had been tricked, quite amusingly, by someone asking for a shout out to his grandad who had helped beat the Nazis, accompanied by a picture of a young Stalin. I’d missed it at the time.

Anyway, on it came throughout the evening, retweets, favourites, questions, statements of the obvious, snark…. It was weird, and unexpected, and kind of exciting. It was like I’d done something really good, rather than just stealing someone else’s old joke. And I was able to track exactly how good it was. I had pulled some kind of killer move and was getting my reward. I was winning the game.

In his 2013 documentary on video games that changed the world, Charlie Brooker, who knows so much about these things, caused a small stir when he suggested that Twitter was in essence, an online multiplayer game. Considering how high-mindedly people like me talk about social media as platforms for change, tools of democratisation and so on, it’s a provocative view to take. But Brooker is right. Twitter users are engaged in a massive game, possibly without end. We measure the success of individual moves (tweets) with retweets and favourites: keep pulling off these successful moves, and we can see our scores go up, in terms of followers accumulated. Not counting the uber famous, who will get a million retweets for the most grudgingly given “I HEART MY FANS; here’s the merchandise page” tweet, most of us are in this game to some extent.

But the description of Twitter as a game has one problem: Twitter can have real-life consequences.

Periodically (well, every time Grand Theft Auto comes out), Keith Vaz or Susan Greenfield or someone will get terribly upset about the ruination caused to young minds or young morals by all this mindless violence. This game lets you steal cars! Run down old ladies! All sorts of unspeakable things! But GTA and other games let you do nothing of the sort: at best, they let you pretend you’re doing these things. In fact, it’s not even that: it lets you control a character, whose character is already somewhat predetermined, in doing some of these things. You’re essentially engaged in a technologically advanced form of improv theatre. Except far more entertaining.

And this is where the Twitter-as-game thing falters: if I threaten to blow up a plane while playing a normal video game, nothing will happen to me. If I do it on Twitter, well…

Last Sunday a 14-year-old Dutch girl called Sarah got in trouble for tweeting that she was a member of Al Qaeda and was about to do “something big” to an American Airlines flight.

According to Dutch news agency BNO, the exchange went as follows:

“Hello my name’s Ibrahim and I’m from Afghanistan. I’m part of Al Qaida and on June 1st I’m gonna do something really big bye,” the girl, identifying herself only as Sarah, said in Sunday’s tweet. Soon after, American Airlines responded in their own tweet: “Sarah, we take these threats very seriously. Your IP address and details will be forwarded to security and the FBI.”

“omfg I was kidding. … I’m so sorry I’m scared now … I was joking and it was my friend not me, take her IP address not mine. … I was kidding pls don’t I’m just a girl pls … and I’m not from Afghanistan,” the girl said in subsequent tweets, later adding: “I’m just a fangirl pls I don’t have evil thoughts and plus I’m a white girl.”

It’s a stupid thing to do, obviously. But Sarah was playing by the rules of the game. She was being provocative, and, in her mind at least, funny. These are things that get you RTs and followers.

But sadly for Sarah, and the rest of us, there comes a point where social media stops being a game and starts being serious business.

We’ve seen this in the UK, of course, with Paul Chambers and the infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

That entire case was a travesty, because no one at any point believed Chambers even meant to behave threateningly. It’s unlikely anyone really believes Sarah meant anything by her tweet either, but in the order of things so far established, directing a comment at an account (at-ing someone, for want of a better phrase), as the Dutch girl did, is worse than simply referring to them, as Chambers did in his tweet about blowing Doncaster’s Robin Hood airport “sky high”.

Where is all this going to end up? I really don’t know. But I can only reiterate the point made many times before that, intriguingly, with the increasing ease of free speech, we’re seeing the rise of an increasing urge to censor; not just in authorities, but in everyday people.

It’s an urge we have to resist.

This article was originally published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org