29 Apr 2019 | Academic Freedom, News, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106402″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]When conservative Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson was invited to deliver the distinguished Roy H Park Lecture at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s journalism school, outrage exploded online.

Current and former students offered fierce criticism of the choice, especially on Twitter where some called Carlson racist and a propagandist. Many said they were disappointed and ashamed. Carlson, people criticised, was not a journalist, but an entertainer. What business did he have speaking to budding journalists? Others pointed to Carlson’s comments about immigrants — they make the US “poorer and dirtier” — and his critiques of diversity, as well as his use of language, critics say, upholds white supremacy.

Despite the backlash, the school moved forward with the lecture, which was largely uneventful. Students and faculty listened. Some audience members asked pointed questions. And then it was over.

That’s how John Robinson, a professor at UNC-Chapel Hill’s journalism school, remembers it. He understood the outrage but said it was a teachable moment.

“Students aren’t snowflakes. They understand BS when they hear it,” he said. “I just don’t see any evidence that students are intolerant of others’ views when it comes to speakers.”

Yet last month US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to uphold freedom of speech on college campuses in response to a supposed “crisis”.

“Under the guise of speech codes, safe spaces and trigger warnings, these universities have tried to restrict free thought, impose total conformity, and shut down the voices of great young Americans like those here today,” Trump said during the signing ceremony, surrounded by predominantly white students in conservative organisations.

Not much is changing. The order encourages universities to “foster environments that promote open, intellectually engaging, and diverse debate” through the First Amendment — freedom of speech. It requires that universities receiving federal research or education grant money must “promote free inquiry”.

But public universities in the US already have to uphold the First Amendment if they receive funding from the federal government. Further, some academics are arguing that the order could actually hurt freedom of speech by causing universities to self-censor who they invite to campus.

In a survey conducted by professor Tori Ekstrand of UNC-Chapel Hill students, 86 per cent said the university should invite speakers with a variety of viewpoints to campus, including those whose perspectives vary from their own. On the national level, the Knight Foundation found that extreme actions, including violence and shouting down speakers, are largely condemned.

So, who is Trump protecting?

In early April, three students from the University of Arizona protested an on-campus presentation by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents, calling them a “murder patrol” and “an extension of the KKK”. All three students were charged with misdemeanours by police: “interference with the peaceful conduct of an educational institution”; one of the students was also charged with “threats and intimidation”. A county prosecutor has yet to decide if a prosecution will go forward.

Trump has not commented on the incident, but many are following the case because it is unusual for arrests to follow a nonviolent protest, especially one on campus. Commentators have said the strong reprimand was a result of the recent order.

The case in Arizona relates to a larger issue on campuses: punishing students who protest. In 2017 the Goldwater Institute, a conservative think tank, published a report arguing that freedom of speech is under attack on American college campuses — citing “shout downs” that interrupt speakers, safe spaces and restrictive policies. The group created a model bill, establishing punitive measures for students and others who interfere with free-speech — essentially punishing protesters on campus. It also prevents administrators from disinviting speakers, no matter how controversial. Many states, including Arizona and North Carolina, have adopted versions of the Goldwater bill.

In a report on the bill, the American Association of University Professors put it bluntly: the legislation “seeks to support what it sees as the embattled minority of conservatives on campus against the ‘politically correct’ majority”.

And for those who find themselves outside the conservative viewpoint?

“It’s an attempt at intimidation,” said Michael Behrent, vice-president of the AAUP’s North Carolina conference. “The argument is to try and force members of the progressive left … to make them feel threatened and endangered, rather than an attempt to outright block their free speech.”

A chilling effect. And this isn’t the first time Trump has attempted this. In 2016, Trump said he planned to change libel laws to make it easier to sue news organisations. The same year, he threatened to imprison or revoke the citizenship of those who burned the flag.

“What we see coming out of his legacy is this notion of protecting conservative speech,” said Kendric Coleman, a professor at Valdosta University who studied the role of safe spaces in the LGBTQ+ community. Trump “is trying to redefine harassment speech into free speech”.

Technically, hate speech is protected by the US constitution, as long as it doesn’t incite violence. But detractors say some speakers — like white nationalist Richard Spencer, who has been disinvited from a number of events and universities — may actually cross the line into incitement of violence.

But some university administrations are hesitant to actually define the line between protected free-speech and incitement to violence. And with new policies coming from the state and federal level, with the intention of protecting free-speech, that line may only become more blurry.

At the heart of the debate lies this question: Should speech that is harmful to certain groups be protected? In the survey conducted by Ekstrand, 93 per cent said others should be allowed to express unpopular opinions on campus. But that number drops to 61 per cent when that speech is offensive to others.

The Knight Foundation also found that American students consider both protecting free-speech and promoting inclusivity as important to democracy. But only 37 per cent of students identifying as Republican said that it is “extremely important” to promote inclusivity — compared to 63 per cent of Democrats.

This is where policies like Trump’s executive order and the Goldwater bill lie. While the left prioritises inclusivity at the expense of free speech, the right resists in opposition.

At stake remains whose voices receive protection, and whose get censored. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556180903639-20dca59b-8321-10″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 May 2018 | Digital Freedom, European Union, Germany, News, Russia, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”85524″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]For around six decades after WWII ideas, laws and institutions supporting free expression spread across borders globally. Ever more people were liberated from stifling censorship and repression. But in the past decade that development has reversed.

On April 12 Russian lawmakers in the State Duma completed the first reading of a new draft law on social media. Among other things the law requires social media platforms to remove illegal content within 24 hours or risk hefty fines. Sound familiar? If you think you’ve heard this story before it’s because the original draft was what Reporters Without Borders call a “copy-paste” version of the much criticized German Social Network law that went into effect earlier this year. But we can trace the origins back further.

In 2016 the EU-Commission and a number of big tech-firms including Facebook, Twitter and Google, agreed on a Code of Conduct under which these firms commit to removing illegal hate speech within 24 hours. In other words what happens in Brussels doesn’t stay in Brussels. It may spread to Berlin and end up in Moscow, transformed from a voluntary instrument aimed at defending Western democracies to a draconian law used to shore up a regime committed to disrupting Western democracies.

US President Donald Trump’s crusade against “fake news” may also have had serious consequences for press freedom. Because of the First Amendment’s robust protection of free expression Trump is largely powerless to weaponise his war against the “fake news media” and “enemies of the people” that most others refer to as “independent media”.

Yet many other citizens of the world cannot rely on the same degree of legal protection from thin-skinned political leaders eager to filter news and information. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has documented the highest ever number of journalists imprisoned for false news worldwide. And while 21 such cases may not sound catastrophic the message these arrests and convictions send is alarming. And soon more may follow. In April Malaysia criminalised the spread of “news, information, data and reports which is or are wholly or partly false”, with up to six years in prison. Already a Danish citizen has been convicted to one month’s imprisonment for a harmless YouTube video, and presidential candidate Mahathir Mohammed is also being investigated. Kenya is going down the same path with a draconian bill criminalising “false” or “fictitious” information. And while Robert Mueller is investigating whether Trump has been unduly influenced by Russian President Putin, it seems that Putin may well have been influenced by Trump. The above mentioned Russian draft social media law also includes an obligation to delete any “unverified publicly significant information presented as reliable information.” Taken into account the amount of pro-Kremlin propaganda espoused by Russian media such as RT and Sputnik, one can be certain that the definition of “unverified” will align closely with the interests of Putin and his cronies.

But even democracies have fallen for the temptation to define truth. France’s celebrated president Macron has promised to present a bill targeting false information by “to allow rapid blocking of the dissemination of fake news”. While the French initiative may be targeted at election periods it still does not accord well with a joint declaration issued by independent experts from international and regional organisations covering the UN, Europe, the Americans and Africa which stressed that “ general prohibitions on the dissemination of information based on vague and ambiguous ideas, including ‘false news’ or ‘non-objective information’, are incompatible with international standards for restrictions on freedom of expression”.

However, illiberal measures also travel from East to West. In 2012 Russia adopted a law requiring NGOs receiving funds from abroad and involved in “political activities” – a nebulous and all-encompassing term – to register as “foreign agents”. The law is a thinly veiled attempt to delegitimise civil society organisations that may shed critical light on the policies of Putin’s regime. It has affected everything from human rights groups, LGBT-activists and environmental organisations, who must choose between being branded as something akin to enemies of the state or abandon their work in Russia. As such it has strong appeal to other politicians who don’t appreciate a vibrant civil society with its inherent ecosystem of dissent and potential for social and political mobilisation.

One such politician is Victor Orban, prime minister of Hungary’s increasingly illiberal government. In 2017 Orban’s government did its own copy paste job adopting a law requiring NGOs receiving funds from abroad to register as “foreign supported”. A move which should be seen in the light of Orban’s obsession with eliminating the influence of anything or anyone remotely associated with the Hungarian-American philanthropist George Soros whose Open Society Foundation funds organisations promoting liberal and progressive values.

The cross-fertilisation of censorship between regime types and continents is part of the explanation why press freedom has been in retreat for more than a decade. In its recent 2018 World Press Freedom Index Reporters Without Borders identified “growing animosity towards journalists. Hostility towards the media, openly encouraged by political leaders, and the efforts of authoritarian regimes to export their vision of journalism pose a threat to democracies”. This is something borne out by the litany of of media freedom violations reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, which monitors 43 countries. In just the last four years, MMF has logged over 4,200 incidents — a staggering array of curbs on the press that range from physical assault to online threats and murders that have engulfed journalists.

Alarmingly Europe – the heartland of global democracy – has seen the worst regional setbacks in RSF’s index. This development shows that sacrificing free speech to guard against creeping authoritarianism is more likely to embolden than to defeat the enemies of the open society.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”100463″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”http://www.freespeechhistory.com”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

A podcast on the history of free speech.

Why have kings, emperors, and governments killed and imprisoned people to shut them up? And why have countless people risked death and imprisonment to express their beliefs? Jacob Mchangama guides you through the history of free speech from the trial of Socrates to the Great Firewall.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526895517975-5ae07ad7-7137-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Apr 2018 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

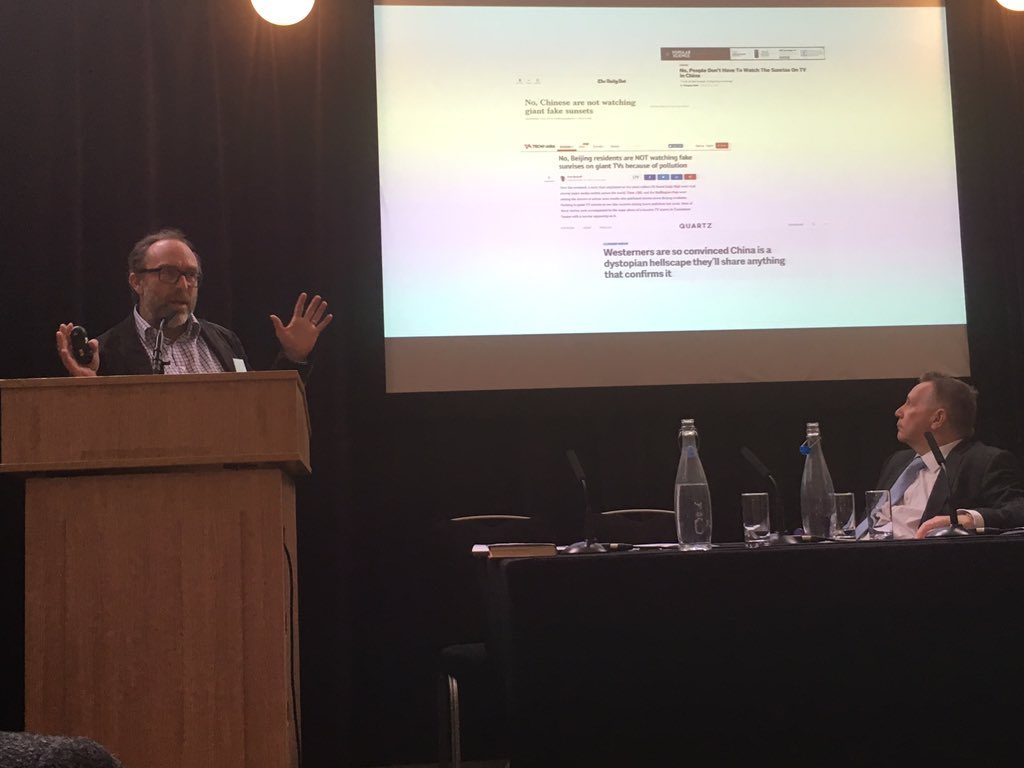

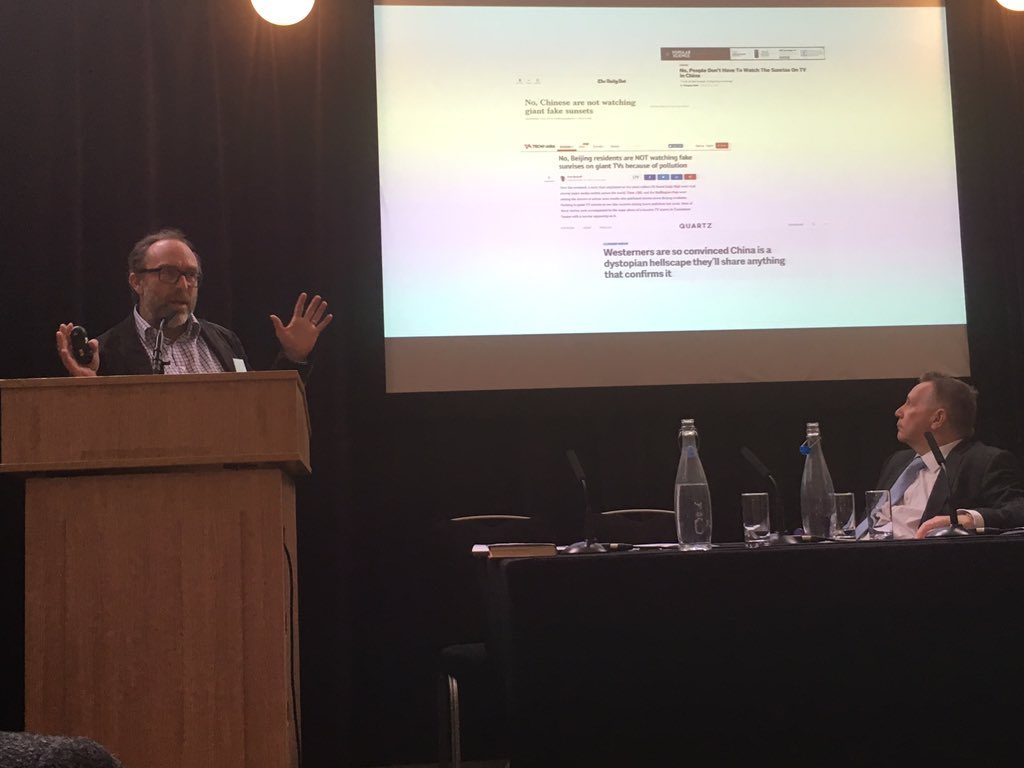

Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales speaking at Westminster Media Forum, April 2018. Credit: Daniel Bruce

“The advertising-only business model has been incredibly destructive for journalism,” said Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales at a Westminster Media Forum event on Thursday 26 April 2018 in London that looked at “fake news”.

“We need to resolve the incentives so that it makes sense and is financially sustainable to do good news,” Wales added.

Wales cited examples of false news stories that had been published on the Mail Online, such as an article featuring a projection of a perfect horizon in Beijing, erected as a way to compensate for the pollution, which proved fake, and a story claiming the Pope supported Donald Trump. He said the Daily Mail of 20 years ago was different. While not what he would choose to read, he thinks there is a place in the media landscape for tabloids, but one running fake news is “a quantum leap we should be very concerned about”.

Suggesting alternatives to advertising-only models, Wales said the Guardian’s donation request box (which he admitted he had consulted on) was an excellent example of how a media organisation can earn money without compromising standards. Meanwhile, a total paywall was very beneficial for some media, in particular financial media, with those readers valuing inside knowledge on the markets, though it would not suit all (the Guardian’s Snowden files, for example, were information he said he would want everyone to be able to access at the same time).

Wales’s concerns about the advertising-only, clickbait-style media models were echoed by others throughout the conference. Drawing an impressive panel of industry experts across media, law and tech, they all united in the view that while fake news meant a myriad of things to many different people, and was not something new, it was nevertheless problematic. Mark Borkowski, founder and head of Borkowski PR, spoke of the 19th-century great moon hoax and how “everything is different and everything is the same” before adding: “The speed at which we expect to get information, without proper fact-checking, is a plague.”

Nic Newman from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism proposed different ways for media to gain more trust, of which “slowing down” was one. Richard Sambrook, former director of global news at the BBC and now director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, said the rise in the number of opinion pieces over evidenced-based journalism was because they were cheaper to commission.

Better education about what constitutes good quality, reliable media was another solution proposed.

“Audiences need better education and sensitivity around algorithms,” said Kathryn Geels, from Digital Catapult.

Katie Lloyd, who is development director at the BBC’s School Report and who runs workshops around the country educating school children into news literacy, said there was a sense of urgency and confusion when it came to the topic and that teachers feel like it really needs to be taught.

“Young people are on the one hand savvy and on the other not so much and need extra help,” said Lloyd, adding that of those children she had interacted with, most knew what fake news was in principle, but not how to spot it.

“When we started talking to teachers they said they didn’t have the tools and the skills to teach it,” she added, tapping into a point raised by head of home news and deputy head of newsgathering at Sky, Sarah Whitehead, who said media education was just as important for older people as it was for the young, as the world of online was not the domain of only one group.

Lloyd also explained that diversity was essential when it came to who was delivering news as people were more likely to trust news from those they could relate to. This was in response to an audience member saying they had spoken to school children who expressed that they respected news on Vice over the BBC. Lloyd agreed that it was essential for news organisations to have a wide range of people in terms of age and background. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524822984082-ad9d065c-d104-5″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Sep 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]President Donald Trump’s decision to take on athletes who choose to kneel during the national anthem at the start of professional sports games shows his disregard for the protections offered by the US Constitution’s First Amendment.

“The ability to choose to ‘take the knee’ in protest at what individuals see as injustice is protected by the First Amendment. While no one is saying the president or anyone else needs to agree with refusing to stand during The Star-Spangled Banner, the protections offered by the US Constitution enable Americans to make their own ‘statements’. Acting in accordance with the rights enshrined in the Constitution is respecting the ideals that the national anthem represents,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship said.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on free speech” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Index is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views. Join our mailing list to get our weekly newsletter.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506347728698-e036ca33-8297-5″ taxonomies=”986″][/vc_column][/vc_row]