Padraig Reidy: Gerry Adams’ half-remembered Republican mythology

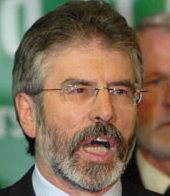

Gerry Adams is the leader of Sinn Féin, the party currently polling higher than any other in Ireland. Last week, Adams, who for many years had the very sound of his voice banned from the airwaves in both Ireland and Britain, due to his connections with the illegal Provisional IRA, told a funny little story at a fundraiser in New York.

Discussing one Irish newspaper’s hostility to his party, Adams told the assembled of how Michael Collins, the Irish War of Independence leader, had dealt with the Irish Independent:

“He went in, sent volunteers in, to the offices, held the editor at gunpoint, and destroyed the entire printing press. That’s what he did. Now I can just see the headline in the Independent tomorrow, I’m obviously not advocating that”, said Adams.

As with much half-remembered Republican mythology, this wasn’t the whole story. As Ian Keneally, author of The Paper Wall: Newspapers and Propaganda in Ireland, 1919-21, related in the Irish Times, the Irish Independent had been broadly sympathetic to the cause of Irish freedom throughout the War of Independence, while deploring individual acts of violence. In the case Adams alluded to, a group of IRA men had indeed entered the Irish Independent offices and threatened the editor, Timothy Harrington, after the paper described a failed IRA ambush as “a deplorable outrage”. The leader of the IRA grouping, Peadar Clancy, said that the newspaper had “endeavoured to misrepresent the sympathies and opinions of the Irish people”. While some damage was done to the Irish Independent’s printing presses, the paper did not shut down.

Ironically for Adams, given his invocation of the fabled Michael Collins, the Irish Independent found itself in deep trouble with British forces for publishing a letter by the IRA leader in December 1920. On that occasion, British “Auxiliaries” entered the newspaper’s offices and literally held a gun to a staff member’s head, warning the paper never to print anything by Collins again. The threat worked.

Historical rigour aside, Adams’s comments obviously didn’t find much favour among journalists. The World Association of Newspapers wrote to Adams calling on him “to retract these comments and to publicly affirm your abhorrence of all forms of violence against journalists”. Adams has refused to do so, citing the hypocrisy of attitudes to the Collins & Co war-of-independence era IRA and the modern (now, we are told, departed) Provisional IRA. In this, he may have a small point, though this is an issue for Irish society at large and not just the newspapers (this cartoon captures that problem neatly).

One could excuse Adams’s allusions as the work of the mind behind his famously quirky, often tongue-in-cheek Twitter account, but there are several background issues that make the whole thing a little uncomfortable.

Firstly, the newspaper group involved has lost two journalists to gunmen in the past 20 years: Veronica Guerin of the Sunday Independent, murdered by gangsters in 1996, and Martin O’Hagan of the Sunday World, shot by loyalist paramilitaries in 2001. Jokes about threats to the Independent News & Media journalists carry that baggage, even if unintended.

Secondly, Adams and his party are currently under scrutiny over an alleged IRA sexual abuse cover up. A woman named Maria Cahill – a relative of Provisional IRA founder Joe Cahill – claims that she was raped by an IRA member, and that the organisation subsequently attempted to cover up the crime. Cahill claims she raised the issue directly with Adams (who, it should be stated for the record, says he has never been a member of the IRA, but nonetheless is viewed as the leader of that particular strand of Irish republicanism), but that justice was not done. Adams’s has already faced criticism for the alleged cover up of his brother Liam’s paedophilic assaults on family members.

Thirdly, Ireland is a country on edge at the moment. The Fine Gael/Labour coalition government’s disastrous handling of proposed water metering and charges has led to previously rarely seen nationwide protests. Having almost cast the previously dominant Fianna Fáil party into oblivion in 2011, Irish voters had hoped they could put faith in a new government. But now, once again, they feel lied to by politicians who do not seem to have the wishes of the population at heart. The perception is that the new water metering system is just another assault on people who have suffered enough after years of boom, bust and bank bailouts.

Into this already toxic mix comes media mogul Denis O’Brien, owner of, among other outlets, the Irish Independent. It is widely believed that O’Brien is supportive of the new watering metering system as Irish Water will eventually be privatised, and he will buy it. O’Brien has a stake in Siteserv, the company contracted to install water meters.

It is not a huge leap to imagine that O’Brien’s papers may be enthusiastic about water charges, and perhaps unsympathetic to protesters. And it’s not difficult to imagine anger being turned against Independent group journalists. After pictures of a brick being thrown at a Garda [police] car during a water protest in Dublin last week were published by the Sunday Independent, many online claimed the image had been photoshopped by the mendacious “Sindo” . This was clearly untrue, but the rumours demonstrated the distrust of institutions, including the press, that now permeates Irish society, and from which upstart Sinn Fein stands most to gain. Former Sinn Féin publicity officer Danny Morrison subsequently tweeted the address of Independent Newspapers, along with a picture of a wall missing a brick. Was he adding to the conspiracy theory? Or was he suggesting violent action against the Independent, in classic I-know-where-you-live style? See how easily the close-up nature of Irish media, politics and public life can set the mind racing?

The government has now proposed new water measures, which it hopes will quell the unrest. But the anti-press, anti-politics rhetoric may have gone too far for that, and in the run up to the centenary of Ireland’s “revolutionary period” of 1916-1923, when romantic rebellion ruled all, little will be gained by any party attempting to present itself as the voice of a reasonable settlement.

This article was posted on 20 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org