22 Apr 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society

In 2013, by way of abundant caution, Harper Collins India decided to pixellate a total of nine panels, including all the close-ups of penises in David Brown’s graphic novel “Paying for It.” While the content, in which Brown narrated his encounters with sex-workers, was left untouched, the publishers were wary of India’s laws against obscenity which make the depiction of nudity almost verboten. This is because a sheet of prudery covers any sexual expression and also governs the legal regulation of sexual speech.

Hence, many welcomed the Indian Supreme Court’s February 2014 ruling that merely because a picture showed nudity, it wouldn’t be caught within the obscenity net- “a picture can be deemed obscene only if it is lascivious, appeals to prurient interests and tends to deprave and corrupt those likely to read, see or hear it,” and having a redeeming social value would save it from being censored.

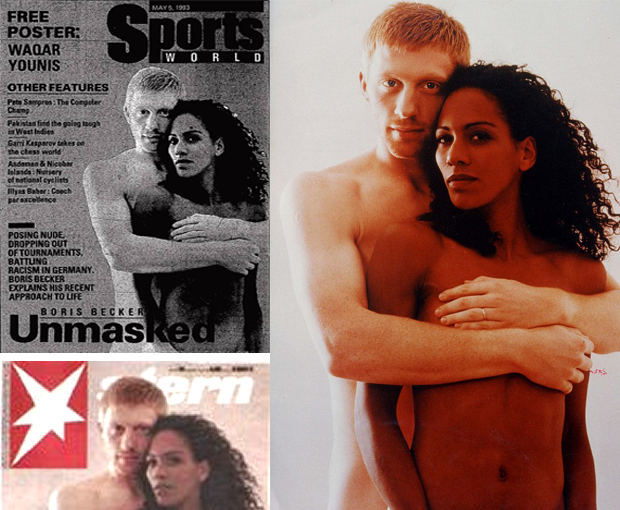

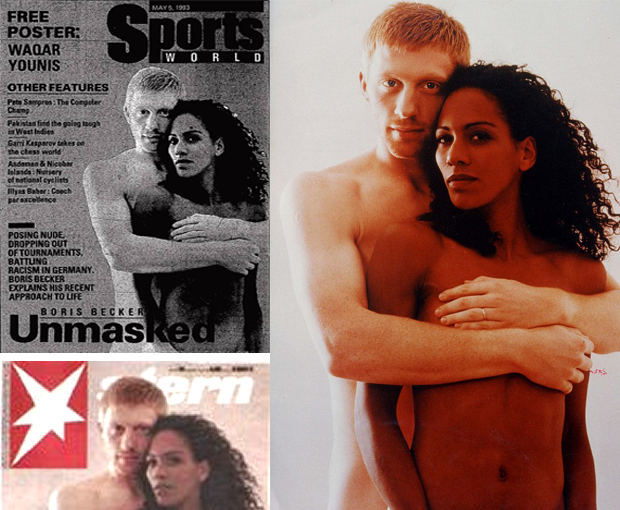

The decision came in an appeal filed in 1993. Sports World, a magazine published from Calcutta, had reproduced the photo on the cover of German magazine Stern. In that photograph, Boris Becker had posed nude with his then fiancée Barbara Feltus; it was his way of protesting against the racist abuse the couple were being subjected to. A solicitous lawyer dragged Sports World to court, alleging that the morals of society and young, impressionable minds were in jeopardy. He cited Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code which prohibits and penalises any form of expression tending towards prurience and encouraging depravity in the readers or viewers. The court rejected the contention, holding that the Hicklin’s Test for determining obscenity has become obsolete, besides imposing unreasonable fetters on the freedom of expression. This test, formulated by the House of Lords in 1868 in Regina v. Hicklin stipulated that ‘‘The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.’’

Instead, the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Roth – wherein “contemporary community standards” were held to be a far more reasonable arbiter, was directed to be adopted. The court also affirmatively cited the decision in Butler which, while upholding the test in Roth, added that anything which showed undue exploitation of sex or degrading treatment of women would remain prohibited.

While the Hicklin’s Test being jettisoned is a cause of relief, the judgement by no means can be held as finally freeing Indian law from the shackles of “comstockery.” George Bernard Shaw had coined this term in 1905 while raging against Anthony Comstock who had taken it upon himself to rid American society of vice. For Comstock, lust and sexual desire were abhorrent, and as he candidly proclaimed anything which even remotely arouses any sexual desire was to be dealt with in the most stringent manner. No wonder he had called Shaw an “Irish smut-peddler” in retaliation.

Gymnophobia, or the fear of nudity, isn’t something new to India’s Supreme Court. Also, it has always been female nudity and the fear of sexual desire which have governed the Court’s opinions. Its image-blaming position has repeatedly been used to reinforce the assumption that sexually explicit images trigger urges in men for which they cannot be held responsible. Depictions of nudity WERE condoned only if they achieved some “laudable social purpose” such as encouraging family planning or making people aware of caste-based atrocities. As Martha Nussbaum points out, collapsing the “disgust” for the nude female body with male sexual arousal and regarding sex as something furtive and impure results in the revulsion being projected on to the female body, thereby making the legal definition of obscenity collude with misogyny.

The present decision is no different. Because Feltus’ breasts were covered by Becker’s arm, and also because Feltus’ father was the photographer, it was held that only the most depraved mind would be aroused and titillated by the magazine cover. Most troubling of all is the overt reliance on contemporary community standards. True, that Indian society has evolved since 1993, but as Brenda Cossman details the scene in Canada in Butler’s aftermath, community standards became a rubric for majoritarian sexual hegemony, resulting in persecution and censorship by prudish vigilantes. And of course, it goes without saying that the search for “redeeming social value” usually ends at puritans’ doorsteps.

Comstockery’s tattered banner, emblazoned with “Morals, not art!” flies aflutter in India.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Feb 2014 | Digital Freedom, India, News and features

(Image: Shutterstock)

Lord Chief Justice Campbell, while introducing The Obscene Publications Act 1857, described pornography as “poison more deadly than prussic acid, strychnine or arsenic” and insisted that the law was imperative to protect women, children and the feeble-minded.

The Indian Supreme Court’s observations and directions while hearing a petition in which online pornography is blamed for of the “epidemic” of rape and sexual violence is redolent of the pornophobia which had gripped the puritanical English legal system in the Victorian era. It is also a stark reminder of the befuddling and dangerous consequences of internet filters, as is being seen in the United Kingdom.

On 27 January, one of the defendants, the Internet Service Providers Association India (ISPAI) while stating that they would not indulge in voluntary censorship, posed a more challenging question — since there is no granular distinction to be made between “high art” and pornography, since temple sculptures can simultaneously be interpreted as both divine and obscene, how could they decide what to block and what to allow. On 28 January, all liberty-loving Indians were aghast at the Supreme Court’s intransigence on homosexual sex.

Taken together, these incidents portend to consequences more pernicious than just a chilling effect on free expression. As Lynda Nead contends, drawing a distinction between sublime and profane seeks to serve a social legitimising function which result in moral policing and violations of the rights of many.

Does pornography cause rape? Justice Douglas’ statement in Ginsberg — “Censors, of course, are propelled by their own neuroses” — and Ronald Dworkin’s reply to Katherine MacKinnon’s “breathtaking hyperbole” remain the most plausible answers to date, not a single study has been able to irrefutably prove correlation, let alone causation. However, Indian courts’ treatment of pornography has been ironic because exposure to obscene and sexually explicit material has been treated as a mitigating factor in rape sentencing. Reepik Ravinder and Phul Singh are two examples of rapists being regarded as victims of the “sex explosion” on celluloid. Not only that, a “ministry of psychic health and moral values” has also been directed to be established to nip this epidemic of vulgarity in the bud.

Justice Potter Stewart’s aphorism “I know it when I see it” holds true for any “definition” of pornography — even today. All we have got is a mystifying epithetic tautology — prurient, lewd, filthy, repulsive, which does no service to the clarity of judicial vision. It is easier to treat pornography as an accused, rather than an offence, because tropes and stereotypes make for poor and unjust legal definitions.

The plea to criminalise browser histories suffers from several grave elisions. For one, irrefutable evidence of correlation, let alone causation, between pornography and sexual violence or depravity is conspicuous by its absence. Though Delhi has a high rate of reported rapes, Google Trends data from 2013 shows more people in the apparently conservative bastions of Gujarat and West Bengal were searching for pornography online.

Most significantly, an obscurantist idyll defines the average consumer and purposes of online pornography. Evidence dispels the notion of only rapacious, lustful men devouring pornography. A 2008 survey reported one in five women watching and approving of porn. Forty-five percent of women who watched pornography also made their own porn videos, and stated how it had helped them being sexually inventive and more intimate with their partners. Another survey, deemed to be the most comprehensive, shows 60 percent women and 80 percent men admitting to accessing sexually explicit content online. Significantly, 30 percent of women respondents said that such content deals with sexual and reproductive health and romance, too. More significant is the response that usage of pornography improved couples’ sex lives.

Moreover, the upshots of dragnet internet filters are reasons for grave consternation. Google AdSense mistook an author’s memoir for pornography and blocked it. In reverse irony, smut sites got caught in an attempt to prevent bureaucrats from surfing sites related to the stock market. And since algorithms do not have a mind of their own, Christopher Hitchens’s polemic against Mother Teresa “The Missionary Position” might also lose its immunity.

India’s information technology law remains riddled with fuzzy definitions, and right now Google, stands indicted for defamation. A ban on internet pornography would further queer the pitch for intermediary liability, thereby delivering another blow to free speech.

Given the climate of legal homophobia, a reference to the aftermath of Canada’s ban on pornography becomes pertinent. There was a sustained persecution of bookstores stocking gay and lesbian literature, comics included, and 70 percent of prosecutions were of homosexual pornography. Besides, even if there were only opt-in filters, it would entail identifying one’s sexual preferences. And where demands for arresting homosexuals are raised on the flimsiest of pretexts, one would become a sitting duck for privacy breaches and criminal prosecution.

One can only wish these apprehensions, and not pornophobia, inform the Supreme Court’s decision.

This article was posted on February 7 2014 at indexoncensorship.org