Labour Party conference: No place for a free press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

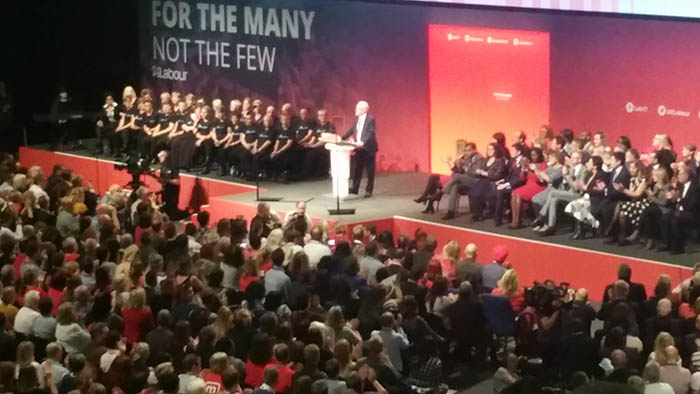

Jeremy Corbyn speaks at Labour Party conference in Brighton, September 2017. Credit: DaveLevy/Flickr

During his first speech at conference as Labour Party leader in September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn called for an end to “personal abuse” and urged delegates to “treat people with respect”.

“Cut out the cyber-bullying and especially the misogynistic abuse online,” he added. “I want kinder politics.”

Two years on the message hasn’t gotten through.

On 24 September 2017, the second day of this year’s party conference, BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned bodyguards after receiving abusive threats online.

The BBC had also decided to bolster Kuenssberg’s personal protection during the general election in June after she faced threats over alleged bias in her reporting surrounding Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. She has also been accused of partiality by Conservative and Ukip supporters.

“It is unprecedented that a journalist would need protection to do her job covering a political conference in the UK, which makes this all the more troubling,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s’ Mapping Media Freedom project, said. “Laura’s case indicates that sexist online abuse against women journalists has become part of the job, and it’s affecting not only the safety of reporters but also a functioning free press.”

Two other journalists were refused entry altogether to the conference. On 23 September, Sussex police refused to give Huck magazine editor Michael Segalov a press security clearance required to attend. Segalov wrote that he applied for press accreditation three months prior to the conference but was informed the evening of 19 September that it had been denied based on the police’s refusal to grant him security clearance.

“Rather than provide reasons and rationale for our journalistic freedom being curtailed, the police said they would not divulge why they made their call,” Segalov wrote. He has never been arrested, charged or convicted of any crime.

“This might be a single incident, but the repercussions should it go unchallenged are worrying. The police restricting the rights of a journalist from attending a political event without giving any rationale, basis or reason puts our civil liberties on the line.”

On 24 September, Michael Walker, a left-wing journalist working for Novara Media, was also barred from entering by police.

“Barring reporters is a form of censorship,” Machlin added. “Political parties interfering with access to events undermines key parts of democracy and sends a clear message from the labour party to all other journalists.”

Earlier this year, Corbyn’s press team barred Buzzed from campaign events. On 9 May, in the run-up to the general election, a senior Corbyn aide told BuzzFeed News political editor Jim Waterson that his access was limited and that the website’s access to the Labour leader would be limited for the rest of the campaign. This was because of an interview with Corbyn published on 8 May had “disrupted media coverage of Labour’s launch event”, the website reported.

Buzzfeed published a piece quoting Corbyn that he remain as the party’s leader even if he lost the election. Corbyn told the BBC he had only said he would stay in power because they would win. BuzzFeed then published an extract of the interview, which showed they had quoted him accurately.

Waterson later regained access to the leader.

Such violations to media freedom are not limited to the Labour Party, however. Also in the run-up to the election, three journalists for Cornwall Live were shut in a room, prevented from filming and severely limited on what questions they could ask during Conservative prime minister Theresa May’s visit to a factory in Cornwall.

A reporter from Cornwell Live who was live-blogging the event wrote: “We’ve been told by the PM’s press team that we were not allowed to stand outside to see Theresa May arrive.”

On two occasions in April 2017, Conservative-run Thurrock Council in Essex said they would restrict access to journalists who “do not reflect the council’s position accurately”.

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire in June, the Kensington and Chelsea Council, which has been Conservative-run since 1964, tried to prevent journalists from attending its first after the atrocity. The council had sought to exclude the public and media from the cabinet meeting, arguing their presence would risk disorder. But after a legal challenge from five media organisations, a high court judge ordered the council to allow accredited journalists to attend half an hour before the meeting was due to start. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1507044011187-4d3c340a-bdf9-4″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]