12 Sep 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Kerry Hudson, Chen Xiwo, Elif Shafak, Meera Selva, Steven Borowiec, Brian Patten and Dean Atta”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

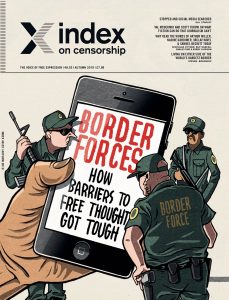

Border forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how borders are getting tougher, journalists are being stopped, visas refused and border officials are snooping into our social media profiles and personal messages. Nations are looking to surveil our thoughts before allowing us to come into their countries and so limiting freedom of expression and the free flow of ideas.

In this issue Steven Borowiec reports from South Korea about how the law means that you can be prosecuted for contacting your relatives in the north without permission; Meera Selva looks at how internet shutdowns are being used round the world to prevent people communicating, most recently in Kashmir; Mark Frary gives tips for LGBT people on how to protect themselves when crossing borders into countries where they might face discrimination. Charlotte Bailey and Jan Fox look at how it is getting tougher in the UK and USA for artists, writers and academics to get visas; and Kaya Genç digs into Turkey’s censorship of the internet. In the rest of the magazine, writers Emilie Pine, Elif Shafak and Kerry Hudson, and theatre director Nicholas Hytner reflect on past famous Index contributors, Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Samuel Beckett and Arthur Miller. We have an extract of the script of the 1977 film Le Camion by Marguerite Duras which has never appeared in English before, and poems by taboo-breaking poet Dean Atta and the Liverpool Poet Brian Patten. We also have an extract of a story by censored Chinese writer Chen Xiwo about a mother and her daughter and their abusive relationship. Plus Index magazine’s first ever crossword by Herbashe.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Border forces: how barriers to free thought got tough”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Big brother at the border by Rachael Jolley

Switch off, we’re landing! by Kaya Genç Be prepared that if you visit Turkey online access is restricted

Culture can “challenge” disinformation by Irene Caselli Migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe are often seen as statistics, but artists are trying to tell stories to change that

Lines of duty by Laura Silvia Battaglia It’s tough for journalists to visit Yemen, our reporter talks about how she does it

Locking the gates by Jan Fox Writers, artists, academics and musicians are self-censoring as they worry about getting visas to go to the USA

Reaching for the off switch by Meera Selva Internet shutdowns are growing as nations seek to control public access to information

Hiding your true self by Mark Frary LGBT people face particular discrimination at some international borders

They shall not pass by Stephen Woodman Journalists and activists crossing between Mexico and the USA are being systematically targeted, sometimes sent back by officials using people trafficking laws

“UK border policy damages credibility” by Charlotte Bailey Festival directors say the UK border policy is forcing artists to stop visiting

Ten tips for a safe crossing by Ela Stapley Our digital security expert gives advice on how to keep your information secure at borders

Export laws by Ryan Gallagher China is selling on surveillance technology to the rest of the world

At the world’s toughest border by Steven Borowiec South Koreans face prison for keeping in touch with their North Korean family

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson Bees and herbaceous borders

Inside the silent zone by Silvia Nortes Journalists are being stopped from reporting the disputed north African Western Sahara region

The great news wall of China by Karoline Kan China is spinning its version of the Hong Kong protests to control the news

Kenya: who is watching you? by Wana Udobang Kenyan journalist Catherine Gicheru is worried her country knows everything about her

Top ten states closing their doors to ideas by Mark Frary We look at countries which seek to stop ideas circulating[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Small victories do count by Jodie Ginsberg The kind of individual support Index gives people living under oppressive regimes is a vital step towards wider change[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Germany’s surveillance fears by Cathrin Schaer Thirty years on from the fall of the Berlin wall and the disbanding of the Stasi, Germans worry about who is watching them

Freestyle portraits by Rachael Jolley Cartoonists Kanika Mishra from India, Pedro X Molina from Nicaragua and China’s Badiucao put threats to free expression into pictures

Tackling news stories that journalists aren’t writing by Alison Flood Crime writers Scott Turow, Val McDermid, Massimo Carlotto and Ahmet Altan talk about how the inspiration for their fiction comes from real life stories

Mosul’s new chapter by Omar Mohammed What do students think about the new books arriving at Mosul library, after Isis destroyed the previous building and collection?

The [REDACTED] crossword by Herbashe The first ever Index crossword based on a theme central to the magazine

Cries from the last century and lessons for today by Sally Gimson Nadine Gordimer, Václav Havel, Samuel Beckett and Arthur Miller all wrote for Index. We asked modern day writers Elif Shafak, Kerry Hudson and Emilie Pine plus theatre director Nicholas Hytner why the writing is still relevant

In memory of Andrew Graham-Yooll by Rachael Jolley Remembering the former Index editor who risked his life to report from Argentina during the worst years of the dictatorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Backed into a corner by love by Chen Xiwo A newly translated story by censored Chinese writer about the abusive relationship between a mother and daughter plus an interview with the author

On the road by Marguerite Duras The first English translation of an extract from the screenplay of the 1977 film Le Camion by one of the greatest French writers of the 20th century

Muting young voices by Brian Patten Two poems, one written exclusively for Index, about how the exam culture in schools can destroy creativity by the Liverpool Poet

Finding poetry in trauma by Dean Atta Male rape is still a taboo subject, but very little is off-limits for this award-winning writer from London who has written an exclusive poem for Index[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]Index around the world: Tales of the unexpected by Sally Gimson and Lewis Jennings Index has started a new media monitoring project and has been telling folk stories at this summer’s festivals[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Endnote: Macho politics drive academic closures by Sally Gimson Academics who teach gender studies are losing their jobs and their funding as populist leaders attack “gender ideology”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Sep 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

Novelist

Elif Shafak is an award-winning Turkish novelist and advocate for free expression. Her latest novel 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World has been long-listed for the Booker Prize.

Novelist

The award-winning novelist Kerry Hudson’s memoir Lowborn captured the imagination of the British public this year because of her vivid description of her dysfunctional family and growing up in poverty in the UK.

Writer

Chen Xiwo is a censored Chinese author, most famous for his collection of stories The Book of Sins which was published in English in 2014. His controversial novella I Love My Mum remains banned in China

18 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Russian, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Кампания против журналистов, которые освещали преследования гомосексуалистов в Чечне, чётко демонстрирует опасности вещания истины в этом коррумпированном государстве. Чеченский журналист описывает сложности”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Протестующие привлекают внимание к нападениям на ЛГБТ в Чечне, Торонто, Канада, Март, JasonParis/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Единственное правило работы журналистов в Чечне: мы все являемся частью пресс-службы Рамзана Кадырова. После прихода к власти в качестве главы Республики в 2007, СМИ превратились в личный инструмент пропаганды Кадырова. Однажды меня почти уволили за использование в новостях кадров с бывшим президентом республики Алу Алкхановым, предшественником Кадырова. Алкханов хороший политик, но Кадыров его не любит. Именно по этой причине нельзя упоминать его имя. Была другая ситуация – я записывал интервью с человеком, которого пытали Чеченские власти. После выхода статьи он был вынужден бежать из страны, чтобы остаться в живых. Я до сих пор виню себя в той ситуации.

Теперь журналисты знают о чём они могут и не могут докладывать, чтобы оставаться в безопасности и продолжать свою работу. К сожалению, писать можно не о многом. Основной темой для любой публикации является Кадыров, его семья и родственники. Практически все новости, исходящие из чеченских СМИ, упоминают его. Репортажи могут касаться самого главы Чечни; его отца, который был убит в 2004; его матери, которая возглавляет благотворительный фонд; или его жены и детей. Начиная от новостей про политику и заканчивая спортом. Например, выходит заголовок про участь Кадырова в репетиции танцевального ансамбля, где он похвалил танцоров или вручил солисту ключи от машины или даже от квартиры. Другой репортаж выходит про то, как Рамзан посетил ежегодный турнир смешанных боевых искусств в Грозном или как Кадыров в больнице распространяет конверты с деньгами для пациентов. Главу Чечни не упоминают только в прогнозе погоды.

Телевидение используется не только для пропаганды, но и для запугивания. Репортажи про людей, просящих прощения за жалобы на власть, получают самое пристальное внимание. Вот как это происходит: в социальных СМИ кто-то жалуется на государство, говорит о коррупции, задержке заработной платы или о похищении. Жалоба рассматривается властями, которые находят, избивают или угрожают автору, потом включается камера и человека заставляют публично приносить извинения.

Вот ещё один пример. Когда Кадыров начал пользоваться Инстаграмом, чеченцы получили возможность непосредственного обращения к нему через социальные сети. Наблюдая то, как он дарит квартиры, автомобили и дорогие подарки уважаемым людям, граждане начали писать про свои проблемы: кто-то не имеет дома, у кого-то больной ребёнок, у кого-то нету работы, у кого-то большая недоплата. Кадыров ответил почти на все сообщения. Специальная группа связалась с авторами просьб, они выехали по соответствующих адресах и выяснили каждую ситуацию

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

На первый взгляд, все выглядело гуманно, но, по сути, группа была создана чтобы уберечь Кадырова от проблем людей. Часто «проверка» заканчивалась докладом по телевизору, утверждая, что автор жалобы – лодырь или самозванец.

В Чечне также есть «ферма троллей». Организация расположена в одном из зданий комплекса Город Грозный. В нем работает дюжина человек, которые постоянно следят за чеченскими и русскими средствами массовой информации и пишут замечания по всей информации, которая касается Кадырова или Чечни. Если новости позитивные, то сотрудники со всем соглашаются. Плохие новости – отвергают. Например, «заявление», написанное мужчиной по имени Николай из Архангельска, гласило: «Вчера я вернулся из Чечни. Похищений там нету. Все люди любят Кадырова. Грозный – самый безопасный город в мире».

За такую работу сотрудники получают хорошую зарплату. Некоторые работники средств массовой информации также награждаются премиями за распространение позитивных новостей о Чечне в социальных СМИ.

В стране существуют независимые средства массовой информации из России и других мест, но им тоже не просто работать. Кадыров неоднократно заявлял – такие средства массовой информации, как Русское Эхо Москвы, Новая газета, РБК, Дождь и Медуза, являются коварными, враждебными СМИ и провоцируют развал страны. В марте Новая газета опубликовала серию следственных статей о том, что мужчины, подозреваемые в гомосексуализме, были окружены и подвергались пыткам в потайных тюрьмах, но новости были быстро опровергнуты. Алви Каримов, представитель Кадырова, в интервью с агентством новостей Интерфакс, финансируемым российским государством, назвал доклад Новой Газеты «абсолютной ложью», утверждая, что в Чечне нету гомосексуалистов, которые подвергались преследованиям.

Это не просто дискредитация, это угроза – реальное запугиванье прессы. За журналистами из этих изданий почти всегда ведётся наблюдение, их терроризируют, иногда убивают. Два журналиста новой Газеты были убиты во время расследований в Чечне за последние два десятилетия. Репортёру, который работал над репортажем о гомосексуализме, угрожали. На собрании примерно 15 000 человек 3 апреля, советник Кадырова, Адам Шахидов, назвал Новую Газету «врагом нашей веры и нашей родины» и обещал «возмездие», согласно Комитету Защиты Журналистов.

Очень трудно найти людей, которые согласны дать интервью. Простые люди боятся разговаривать с журналистами, а чиновники просто отказаться. Эти информационные источники не могут оставаться анонимными в Чечне, поскольку практически невозможно сохранить конфиденциальность. Чечня невелика; здесь все всех знают. Журналисты могут скрывать своё собственное имя, но для того, чтобы выполнять работу, им необходимо брать интервью у людей, передавать подробности, описывать произошедшие события. С помощью подробных сведений очень легко понять, о чём и о ком была написана статья. Никто не хочет подставлять под угрозу кого-то, кто готов дать интервью, зная на что способны чеченские власти, подавляя несогласие.

Страдает даже иностранная пресса. До недавнего времени она была широко представлена, иностранные журналисты часто приезжали и проводили интервью. Люди более охотно с ними разговаривали, возможно, потому что эти статьи публиковались за рубежом, на иностранных языках и редко переводились. Однако ситуация резко изменилась в марте 2016, когда группа журналистов, путешествующих с активистами в области прав человека, были избиты и серьёзно ранены в соседней Республике Ингушетии. Их машину сожгли, а они оказались в больнице. Никто не сомневался в том, что нападавшие действовали по приказу чеченских властей. После этого инцидента немногие зарубежные журналисты рискуют приезжать в Чечню. Но без них ещё меньше надежды на подачу объективной информации о том, что происходит в Республике.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Автор статьи из Чечни, работал в средствах массовой информации на протяжении более десяти лет. Он хочет остаться анонимным из соображений безопасности

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 years on” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Las violentas represalias que están sufriendo los reporteros que cubren la persecución de los homosexuales en Chechenia pone de relieve los peligros de sacar la verdad a la luz en un estado corrupto. Un periodista checheno habla de las dificultades a las que se enfrenta”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Manifestantes en Toronto (Canadá) marchan para concienciar sobre la situación de las personas LGTB en Chechenia, JasonParis/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Una sola ley gobierna la labor de los periodistas de Chechenia: todos somos parte del servicio de prensa de Ramzan Kadyrov. Desde que Kadyrov llegó al poder en 2007 como jefe de la república, los medios de comunicación se han convertido en su herramienta personal de propaganda. Una vez casi me quedé sin trabajo por utilizar, para un reportaje, metraje en el que salía Alu Aljanov, expresidente de la república y predecesor de Kadyrov. Aljanov es un político decente, pero a Kadyrov no le gusta. Por eso no se puede mencionar su nombre. En otra ocasión, grabé una entrevista con un hombre al que las autoridades chechenas habían torturado. Cuando salió la entrevista a la luz, el hombre tuvo que huir del país para permanecer a salvo. Sigo creyendo es mi culpa.

Los periodistas de aquí y ahora saben lo que pueden y no pueden escribir si quieren mantenerse sanos y salvos. Desgraciadamente, lo que pueden escribir no es mucho. La principal fuente de noticias de cualquier publicación son Kadyrov, su familia y sus parientes. No hay prácticamente una sola historia emitida por los medios chechenos que no nombre a Kadyrov. Tal vez haga referencia al propio jefe de Chechenia; a su padre, asesinado en 2004; a su madre, que dirige una fundación benéfica, o a su mujer e hijos. Así funciona con las noticias de política y hasta con los deportes. Por ejemplo, puede salir un titular diciendo que Kadyrov ha visitado el ensayo de una compañía de danza, ha elogiado a los artistas o le ha entregado al solista las llaves de un coche o incluso de un piso. Otro dirá que Kadyrov se ha pasado por el torneo anual de artes marciales mixtas en Grozny, o mostrará a Kadyrov visitando un hospital y repartiendo sobres de dinero a los pacientes. El único momento de las noticias en el que el jefe de Chechenia no sale nombrado es en el pronóstico meteorológico.

La televisión se utiliza no solo como propaganda sino también como instrumento de intimidación. Las historias que parecen atraer más atención muestran a personas disculpándose ante Kadyrov por haberse quejado de las autoridades. El asunto funciona de la siguiente manera: en las redes sociales, alguien critica a las autoridades y habla de la corrupción, los salarios retenidos o algún secuestro. Las autoridades lo ven, encuentran a su autor y le dan una paliza o lo amenazan, colocan una cámara y lo obligan a disculparse.

Otro ejemplo: cuando Kadyrov empezó a usar Instagram, los chechenos entendieron su presencia en esta red social como una oportunidad de dirigirse a él directamente. Al ver que regalaba pisos, coches y cosas caras a gente distinguida, los ciudadanos empezaron a hablarle de problemas reales, como no tener un techo, tener un hijo enfermo, estar en el paro o cobrar un sueldo ridículamente bajo. Un equipo especial contactaba con el autor de cada petición, acudía a la dirección correspondiente e investigaba la situación. A primera vista, todo muy humanitario; pero, en realidad, el equipo había sido creado para proteger a Kadyrov de los problemas de quienes le hacían peticiones. A menudo la «verificación» terminaba siendo una noticia emitida por televisión en la que denunciaban que la persona en cuestión era un vago o un impostor.

En Chechenia también hay un ejército de trolls de internet. La organización está ubicada en un edificio del complejo de las Torres Grozny-City. Tiene empleadas a una docena de personas que monitorizan constantemente los medios chechenos y rusos y ponen comentarios sobre cualquier cosa que tenga que ver con Kadyrov y con Chechenia. Si es una buena noticia, los empleados de la organización la confirman. Si es mala, la niegan. En una ocasión, un «comentario» escrito por un tal Nikolai de Arjangelsk decía: «Volví ayer de Chechenia. No hay ningún secuestro. Todo el mundo quiere a Kadyrov. Grozny es la ciudad más segura del mundo.»

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Los empleados cobran grandes sumas por su trabajo como trolls. Algunos trabajadores de los medios de comunicación también reciben primas si suben buenas noticias sobre Chechenia a las redes sociales.

Hay medios de comunicación independientes, de Rusia y otros países, que operan en Chechenia, pero también el suyo es un trabajo difícil. Kadyrov dice mucho que los medios de comunicación como Ejo Moskvy, Novaya Gazeta, RBC, Dozhd de Rusia y Meduza de Letonia son traicioneros, hostiles y solo buscan la ruina del país. Por ejemplo, cuando Novaya Gazeta publicó en marzo una serie de artículos de investigación en los que informaban de que estaban atrapando a hombres sospechosos de homosexualidad y torturándolos en prisiones secretas, la historia fue tachada de falsa. Alvi Karimov, portavoz de Kadyrov, describió el reportaje de Novaya Gazeta como “puras mentiras” en una entrevista con la agencia de prensa Interfax, financiada por el estado ruso, en la que decía que no había gais en Chechenia a los que perseguir.

El descrédito no es la única amenaza: los reporteros corren verdadero peligro. Los periodistas de estas publicaciones están sometidos a vigilancia e intimidaciones constantes. A veces los matan. En el último par de décadas, dos periodistas de Novaya Gazeta han sido asesinados mientras cubrían noticias de Chechenia, y el reportero que trabajaba en los casos sobre homosexualidad ha recibido amenazas. En una reunión de unos 15.000 hombres el pasado 3 de abril, Adam Shahidov, consejero de Kadyrov, llamó a los periodistas de Novaya Gazeta «enemigos de nuestra fe y nuestra patria», y prometió «venganza», según denunció el Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas.

Por otro lado, están las dificultades de encontrar gente a la que entrevistar. La gente normal tiene demasiado miedo de hablar con periodistas y los cargos públicos simplemente se niegan a hacerlo. Estos medios de comunicación no pueden contar con corresponsales anónimos en Chechenia porque es casi imposible permanecer en el anonimato. Chechenia es pequeña; todo el mundo se conoce. Los periodistas pueden ocultar su nombre, pero si quieren realizar una labor periodística normal, necesitan entrevistar a gente, dar detalles, describir lo sucedido. Es muy fácil usar esos detalles para entender acerca de qué y de quién se ha escrito el artículo en cuestión. Sabiendo de lo que son capaces las autoridades chechenas en lo que respecta a aplastar la disidencia, nadie quiere exponer alguien solo porque acceda a que lo entrevisten.

Hasta la prensa extranjera sufre. Hasta hace poco estaba bien representada, y los periodistas venían y realizaban entrevistas a menudo. La gente se sentía más cómoda al hablar con ellos, quizá porque los artículos se publicaban en idiomas extranjeros y raras veces se traducían. Pero la situación cambió drásticamente en marzo de 2016, cuando un grupo de periodistas que viajaban con activistas pro derechos humanos sufrieron palizas y graves lesiones en la república vecina de Ingushetia. Alguien prendió fuego a su vehículo y tuvieron que ser hospitalizados. Nadie dudó por un momento que los atacantes habían actuado por orden de las autoridades chechenas. Tras el incidente, pocos periodistas extranjeros se han arriesgado a venir. Sin ellos, la esperanza de poder ofrecer información veraz sobre lo que está ocurriendo en Chechenia es aún más escasa.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

El autor de este artículo es originario de Chechenia y lleva más de diez años trabajado en medios del país. Ha preferido permanecer anónimo por razones de seguridad.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en verano de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 years on” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine