9 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News, Politics and Society

Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

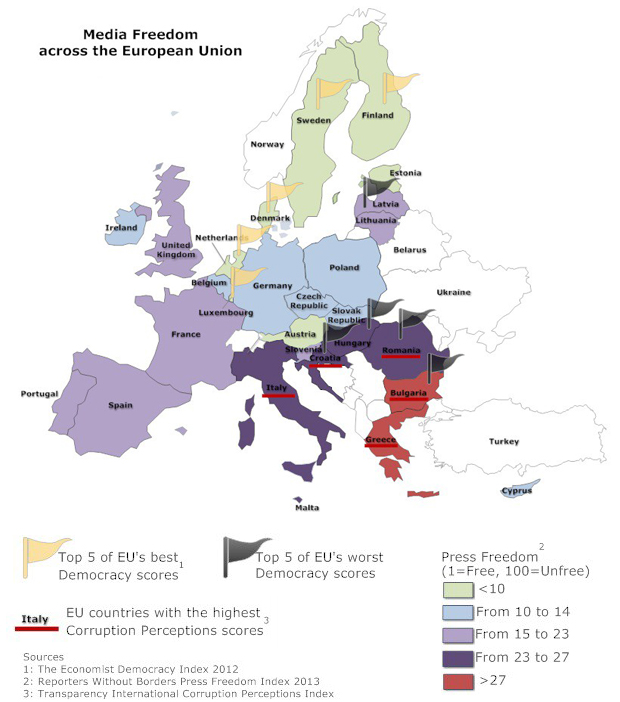

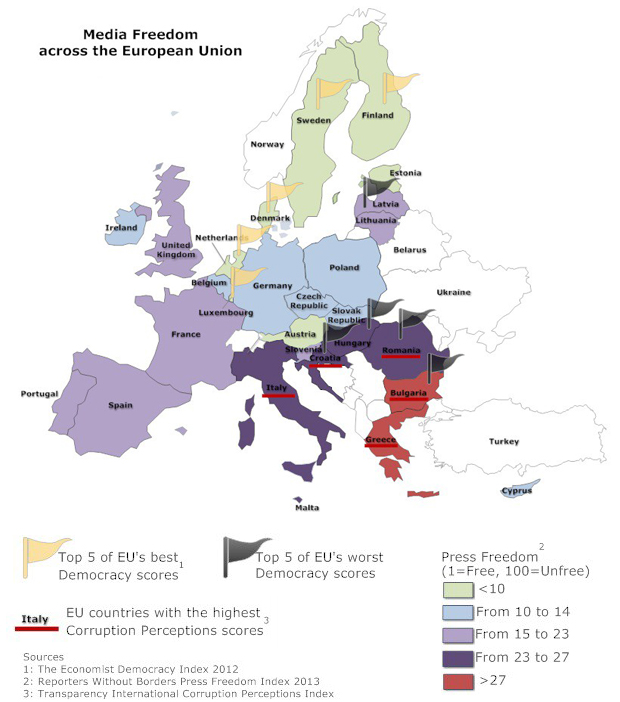

The main threats to media freedom and the work of journalists are from political pressure or pressure exerted by the police, to non-legal means, such as violence and impunity. There have been instances where political pressure against journalists has led to self-censorship in a number of European Union countries. This pressure can manifest itself in a number of ways, from political pressure to influence editorial decisions or block journalists from promotion in state broadcasters to police or security service interventions into media investigations on political corruption.

The European Commission now has a clear competency to protect media freedom and should reflect on how it can deal with political interference in the national media of member states. As the heads of state or government of the EU member states have wider decision-making powers at the European Council this gives a forum for influence and negotiation, but this may also act as a brake on Commission action, thereby protecting media freedom.

Italy presents perhaps the most egregious example of political interference undermining media freedom in a EU member state. Former premier Silvio Berlusconi has used his influence over the media to secure personal political gain on a number of occasions. In 2009 he was thought to be behind RAI decision to stop broadcasting Annozero, a political programme that regularly criticised the government. In the lead up to the 2010 regional elections, Berlusconi’s party pushed through rules which effectively meant that state broadcasters had to either feature over 30 political parties on their talk shows or lose their prime time slots. Notably, Italian state broadcaster RAI refused to show adverts for the Swedish film Videocracy because it claimed the adverts were “offensive” to Silvio Berlusconi.

Under the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Hungary has seen considerable political interference in the media. In September 2011, popular liberal political radio station “Klubrádió” lost its licence following a decision by the Media Authority that experts believed was motivated by political considerations. The licence was reinstated on appeal. In December 2011, state TV journalists went on hunger strike after the face of a prominent Supreme Court judge was airbrushed out of a broadcast by state-run TV channel MTV. Journalists have complained that editors regularly cave into political interference. Germany has also seen instances of political interference in the public and private media. In 2009, the chief editor of German public service broadcaster ZDF, Nikolaus Brender, saw his contract terminated in controversial circumstances. Despite being a well-respected and experienced journalist, Brender’s suitability for the job was questioned by politicians on the channel’s executive board, many of whom represented the ruling Christian Democratic Union. It was decided his contract should not be renewed, a move widely criticised by domestic media, the International Press Institute and Reporters Without Borders, the latter arguing the move was “motivated by party politics” which, it argued, was “a blatant violation of the principle of independence of public broadcasters”. In 2011, the editor of Germany’s (and Europe’s) biggest selling newspaper, Bild, received a voicemail from President Christian Wulff, who threatened “war” on the tabloid if it reported on an unusual personal loan he received.

Police interference in the work of journalists, bloggers and media workers is a concern: there is evidence of police interference across a number of countries, including France, Ireland and Bulgaria. In France, the security services engaged in illegal activity when they spied on Le Monde journalist Gerard Davet during his investigation into Liliane Bettencourt’s alleged illegal financing of President Sarkozy’s political party. In 2011, France’s head of domestic intelligence, Bernard Squarcini, was charged with “illegally collecting data and violating the confidentiality” of the journalists’ sources. In Bulgaria, journalist Boris Mitov was summoned on two occasions to the Sofia City Prosecutor’s office in April 2013 for leaking “state secrets” after he reported a potential conflict of interest within the prosecution team. Of particular concern is Ireland, which has legislation that outlaws contact between ordinary police officers and the media. Clause 62 of the 2005 Garda Siochána Act makes provision for police officers who speak to journalists without authorisation from senior officers to be dismissed, fined up to €75,000 or even face seven years in prison. This law has the potential to criminalise public interest police whistleblowing.[1]

It is worth noting that after whistleblower Edward Snowden attempted to claim asylum in a number of European countries, including Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, the governments of all of these countries stated that he needed to be present in the country to claim asylum. Others went further. Poland’s Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski posted the following statement on Twitter: “I will not give a positive recommendation”, while German Foreign minister Guido Westerwelle said although Germany would review the asylum request “according to the law”, he “could not imagine” that it would be approved. The failure of the EU’s member states to give shelter to Snowden when so much of his work was clearly in the public interest within the European Union shows the scale of the weakness within Europe to stand up for freedom of expression.

Deaths, threats and violence against journalists and media workers

No EU country features in Reporters Without Borders’ 2013 list of deadliest countries for journalists. But since 2010, three journalists have been killed within the European Union. In Bulgaria in January 2010 , a gunman shot and killed Boris Nikolov Tsankov, a journalist who reported on the local mafia, as he walked down a crowded street. The gunman escaped on foot. In Greece, Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption. In Latvia, media owner Grigorijs Nemcovs was the victim of an apparent contract killing, which Reporters Without Borders claims appeared to be carefully planned and executed.103 Nemcovs was also a political activist and deputy mayor, and his newspaper, Million, was renowned for its investigative coverage of political and local government corruption and mismanagement.

While it is rare for journalists to be killed within the EU, the Council of Europe has drawn attention to the fact that violence against journalists does occur in EU countries, particularly in south eastern Europe, including in Greece, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.[2] The South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO) has raised concerns over police violence against journalists covering political protests in many parts of south eastern Europe, particularly in Romania and Greece.

[1] There is an official whistleblowing mechanism instituted by the law, but it is not independent of the police.

[2] William Horsley for rapporteur Mats Johansson, ‘The State of Media Freedom in Europe’, Committee on Culture, Science, Education and Media, Council of Europe (18 June 2012).

8 Jan 2014 | European Union, News, Politics and Society

(Photo: Shutterstock)

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

“Currently the EU does not have the legal competence to act in this area [media plurality] as part of its normal business. In practice, our role involves naming and shaming countries ad hoc, as issues arise. Year after year I return to this Parliament to deal with a different, often serious, case, in a different Member State. I am quite willing to continue to exercise that political pressure on Member States that risk violating our common values. But there’s merit in a more principled way forward.”

Commission Vice President Neelie Kroes

Media plurality is an essential part of guaranteeing the media is able to perform its watchdog function. Without a plurality of opinions, the analysis of political arguments in democracies can be limited.[1] Media experts argue that the European Commission has the clear competency to promote media plurality, through legal instruments such as the Lisbon Treaty and the Maastricht Treaty, but also second EU legislation. Yet, the commission has until now left the promotion of media plurality up to member states. This section will outline the ways in which some member states have failed to protect media plurality. In recent years, Italy has been the most egregious offender. Italy’s failure to protect media plurality has heightened the pressure on the European Commission to act.

The Italian “anomaly” in broadcast media included: duopoly domination in the television market, with the country’s former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi also the owning the country’s largest private television and advertising companies and a legislative vacuum that failed to prevent media concentration, as well as public officials having vested interests in the media. Legislation purportedly designed to deal with media concentration, such as the Gasperri Law of 2004, may have helped preserve them. When Mediaset owner Silvio Berlusconi became Prime Minister, he was in a powerful position, with influence over 80% of the country’s television channels through his private TV stations and considerable influence over public broadcaster RAI. This media concentration was condemned by the European Parliament on two occasions. In order to promote media plurality, in July 2010, the European Commission ruled to remove restrictions on Sky Italia that prevented the satellite broadcaster from moving into terrestrial television, in order to promote media plurality. It is possible that now the EU would have a clearer mandate to intervene using Article 11 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which came into force in 2009.[7] The Commission, however, did not intervene to prevent the conflict of interest between Premier Silvio Berlusconi, his personal media empire and the control he could exercise over the public sector broadcaster.

There are a number of EU member states where media ownership patterns have compromised plurality. A 2013 study by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom showed strong media concentrations prevalent across the EU, with the largest media groups having ownership of an overwhelming percentage of the media. These media concentrations are significantly higher than the equivalent US figures.

|

Netherlands |

UK |

France |

Italy |

| Market share for three largest newspapers |

98.2% |

70% |

70% |

45% |

|

Italy |

Germany |

UK |

France |

Spain |

Share of total advertising spend received by the two largest TV stations

|

79% |

82% |

66% |

62% |

59% |

However, the most concentrated market was the online market. The internet’s ability to facilitate the cheap open transmission of news was expected to break down old media monopolies and allow new entrants to enter the market, improving media plurality. There is some evidence to suggest this is happening: among people who read their news in print in the UK, on average read 1.26 different newspapers; those who read newspapers online read 3.46 news websites.

Yet, many have raised concerns over the convergence of newspapers, TV stations and online portals to produce increasingly larger media corporations.[2] This is echoed by the European Commission’s independent High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism. The High Level Group calls for digital intermediaries, including app stores, news aggregators, search engines and social networks, to be included in assessments of media plurality. The Reuters Institute has called for digital intermediaries to be required to “guarantee that no news content or supplier will be blocked or refused access” (unless the content is illegal).

Media plurality has not been adequately protected by some EU member states. The European Commission now has a clearer competency in this area and has acted in specific national markets. MEPs have expressed concerns over the Commission’s slow response to the crisis in Italian media plurality, a lesson that the Commission must learn from. In the future, with increasing digital and media convergence, the role of the Commission will be crucial for the protection of media plurality; otherwise this convergence could have a significant impact on freedom of expression in Europe.

[1]Index on Censorship, ‘How the European Union can protect freedom of expression’ (December 2012)

[2] p.165, Lawrence Lessig, ‘Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity” (Penguin, 2004)

7 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Media concentration in the EU poses a significant challenge. The media in the EU is significantly more concentrated than in North America, even when taking into consideration explanations of population, geographical size and income. Even by global standards, media concentration in the EU is high.

Another challenge arises from national media regulation, which may both fail to protect plurality and, allow an unnecessary and unacceptable amount of political interference in the way the media works. While the EU does not have an explicit competency to intervene in all matters of media plurality and media freedom, it is not neutral in this debate. A number of initiatives are underway to help better promote media freedom, and in particular media plurality. Free expression advocates, including Index, welcome the fact that the EU is taking the issue of media freedom more seriously.

Media regulation

Across the European Union, media regulation is left to the member states to implement, leading to significant variations in the form and level of media regulation. National regulation must comply with member states’ commitments under the European Convention on Human Rights, but this compliance can only be tested through exhaustive court cases. While the European Commission has, in the past, tended to view its competencies in this area as being limited due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at its possible role in this area. In part, the Commission is acting upon the guidance of the European Parliament, which has expressed significant concerns over the state of media regulation, and in particular with regard to Hungary, where regulation has been criticised for curtailing freedom of expression.

The national models of media regulation across Europe vary significantly, from models of self-regulation to statutory regulation. These models of regulation can impact negatively on freedom of expression through the application of unnecessary sanctions, the regulator’s lack of independence from politicians and laws that create a burdensome environment for online media. Statutory regulation of the print and broadcast media is increasingly anachronistic, raising questions over how the role of journalist or broadcaster should be defined and resulting in a general and increasing confusion about who should be covered by these regulatory structures, if at all. Frameworks that outline laws on defamation and privacy and provide public interest and opinion defences for all would provide clarify for all content producers. In the majority of countries, the broadcast media is regulated by a statutory regulator (due to a scarcity of analogue frequencies that required arbitration in the past), yet, often, the print media is also regulated by statutory bodies, including in Slovenia, Lithuania, Italy; or regulated by specific print media laws and codes, for example in Austria, France, Sweden and Portugal. As we demonstrate below, many EU member states have systems of media regulation that are overly restrictive and fail to protect freedom of expression.

In many EU member states, the system of media regulation allows excessive state interference in the workings of the media. Hungary’s system of media regulation has been criticised by the Council of Europe, the European Parliament and the OSCE for the excessive control statutory bodies exert over the media. The model of “co-regulation” was set up in 2010 through a new comprehensive media law[1], culminating in the creation of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority, which was given statutory powers to fine media organisations up to €727,000, oversaw regulation of all media including online news websites, and acts as an extra-judicial investigator, jury and judge on public complaints. The president of the Media Authority and all five members of the Media Council were delegated exclusively by Hungary’s Fidesz party, which commanded a majority in Parliament. The law forced media outlets to provide “balanced coverage” and had the power to fine reporters if they didn’t disclose their sources in certain circumstances. Organisations that refused to sign up to the regulator faced exemplary fines of up to €727,000 per breach of the law. While the European Commission managed to negotiate to remove some of the most egregious aspects of the law, nothing was done to rectify the political composition of the media council, the source of the original complaint to the Commission.

Hungary is not the only EU member state where politicians have excessive influence over media regulators. In France, the High Council for Broadcasting (CSA), which regulates TV and radio broadcasting, has nine executives appointed by presidential decree, of which three members are directly chosen and appointed by the president, three by the president of the Senate, and three by the president of the National Assembly. According to the Centre for Media and Communication Studies, this system for appointing authorities has the fewest safeguards from governmental influence in the EU.

Many countries have statutory underpinning of the press, which includes the online press, including Austria, France, Italy, Lithuania, Slovenia and Sweden. Some statutory regulation can provide freedom of expression protections to those who voluntarily register with the regulatory body (for instance in Sweden), but in many instances, the regulatory burden and possibility of fines for online media can chill freedom of expression.

The Leveson Inquiry in the UK was established after the extent of the phone-hacking scandal was discovered, revealing how journalists had hacked the phones of victims of crime and high profile figures. Lord Justice Leveson made a number of recommendations in his report, including the statutory underpinning of an “independent” regulatory body, restrictions to limit contact between senior police officers and the press that could inhibit whistleblowing, and exemplary damages for publishers who remain outside the regulator. Of particular concern was the notion of statutory unpinning by what was claimed to be an “independent” and “voluntary” regulator. By setting out the requirements for what the regulator should achieve in law, it introduced some government and political control over the functioning of the media. Even “light” statutory regulation can be revisited, toughened and potentially abused. Combined with exemplary damages for publishers who remained outside the “voluntary” regulator (damages considered to be in breach of Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights by three eminent QCs), the Leveson proposals were damaging to freedom of expression. The situation was compounded by the attempt by a group of Peers in the House of Lords to exert political pressure on the government to regulate the press, potentially sabotaging much-needed reform of the archaic libel laws of England and Wales. This resulted in the government bringing in legislation through the combination of a Royal Charter (the use of the Monarch’s powers to establish a body corporate) and by adding provisions to the Crime and Courts Act (2013) that established the legal basis for exemplary damages. It is arguable that the Leveson proposals have already been used to chill public interest journalism.

In part a response to the dilemma posed by Hungary, but also to wider issues of press regulation raised by the Leveson Inquiry in the UK, vice president of the Commission Neelie Kroes has overseen renewed Commission interest in the area of media regulation. This interest builds upon the possibility of the Commission using new commitments introduced through the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, such as Article 11 of the Charter, which states: “The freedom and pluralism of the media shall be respected.” The Commission is now exploring a variety of options to help protect media freedom, including funding the establishment of the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom and the EU Futures Media Forum. In October 2011, Kroes founded a High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism to look at these issues in more detail. The conclusions were published in January 2013.

Many of the recommendations of the High Level Media Group are useful, in particular the first recommendation: “The EU should be considered competent to act to protect media freedom and pluralism at State level in order to guarantee the substance of the rights granted by the Treaties to EU citizens”. Yet some of the High Level Group’s conclusions do not provide a solution to questions of appropriate legislation within the EU. The group called for all member states to have “independent media councils” that are politically and culturally balanced with a socially diverse membership and have enforcement powers including fines, the power to order printed or broadcast apologies and, particularly concerning, the power to order the removal of (professional) journalistic status.[2] Political balance could be interpreted as political representation on the media councils, when the principle should be that the media is kept free from political interference. This was an issue raised in particular by Hungarian NGOs during the consultation. Also of particular concern is the suggestion that the European Commission should monitor the national media councils with no detail as to how the Commission is held to account, or process for how national media organisations could challenge bad decisions by the Commission. The Commission is awaiting the results of a civil society consultation. Depending on the conclusions of the Commission, stronger protections for media freedom may be considered when a state clearly deviates from established norms.

[1]Act on the Freedom of the Press and the Fundamental Rules on Media Content (the “Press Freedom Act”) and the Media Services and Mass Media Act (or the “Media Act”)

[2] p.7, High Level Media Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism

27 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Since the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, which made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding, the EU has gained an important tool to deal with breaches of fundamental rights.

The Lisbon Treaty also laid the foundation for the EU as a whole to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. Amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (Article 7) gave new powers to the EU to deal with state who breach fundamental rights.

The EU’s accession to the ECHR, which is likely to take place prior to the European elections in June 2014, will help reinforce the power of the ECHR within the EU and in its external policy. Commission lawyers believe that the Lisbon Treaty has made little impact, as the Commission has always been required to assess whether legislation is compatible with the ECHR (through impact assessments and the fundamental rights checklist) and because all EU member states are also signatories to the Convention.[1] Yet external legal experts believe that accession could have a real and significant impact on human rights and freedom of expression internally within the EU as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will be able to rule on cases and apply European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence directly. Currently, CJEU cases take approximately one year to process, whereas cases submitted to the ECHR can take up to 12 years. Therefore, it is likely that a larger number of freedom of expression cases will be heard and resolved more quickly at the CJEU, with a potential positive impact on justice and the implementation of rights in the EU.[2]

The Commission will also build upon Council of Europe standards when drafting laws and agreements that apply to the 28 member states. Now that these rights are legally binding and are subject to formal assessment, this may serve to strengthen rights within the Union.[3] For the first time, a Commissioner assumes responsibility for the promotion of fundamental rights; all members of the European Commission must pledge before the Court of Justice of the European Union that they will uphold the Charter.

The Lisbon Treaty also provides for a mechanism that allows European Union institutions to take action, whether there is a clear risk of a “serious breach” or a “serious and persistent breach”, by a member state in their respect for human rights in Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union. This is an important step forward, which allows for the suspension of voting rights of any government representative found to be in breach of Article 7 at the Council of the European Union. The mechanism is described as a “last resort”, but does potentially provide leverage where states fail to uphold their duty to protect freedom of expression.

Yet within the EU, some remained concerned that the use of Article 7 of the Treaty, while a step forward, is limited in its effectiveness because it is only used as a last resort. Among those who argued this were Commissioner Reding, who called the mechanism the “nuclear option” during a speech addressing the “Copenhagen Dilemma” (the problem of holding states to the human rights commitments they make when they join). In March 2013, in a joint letter sent to Commission President Barroso, the foreign ministers of the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany called for the creation of a mechanism to safeguard principles such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The letter argued there should be an option to cut EU funding for countries that breach their human rights commitments.

It is clear that there is a fair amount of thinking going on internally within the Commission on what to do when member states fail to abide by “European values”. Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these rights.

This thinking has been triggered by recent events in Hungary and Italy, as well as the ongoing issue of corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, which points to a wider problem the EU faces through enlargement: new countries may easily fall short of both their European and international commitments.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Footnotes

[1] Off-record interview with a European Commission lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

[2] Interview with Prof. Andrea Biondi, King’s College London, 22 April 2013.

[3] Interview with lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).