Vidal-Hall on 14 years at Index exposing censorship happening under our nose

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Judith Vidal-Hall at the 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards. Credit: Dimitri Lauder/Index on Censorship

“The invasion of privacy is the reverse side of censorship. If you don’t feel that your privacy is immune, you’re not going to speak out, you’re going to hold your tongue. Or not talk about certain things. So it has this strange underbelly of censorship,” said Judith Vidal-Hall, former editor of Index on Censorship from 1993 to 2007. I meet Vidal-Hall on a sunny afternoon at a river-side cafe in West London to discuss her experiences of editing the magazine. We’re chatting about the internet and the privacy concerns that come with it, a concern that went from almost non-existent to ubiquitous during her time as editor.

“One of the greatest threats to free expression at the moment is privacy,” she added.

Vidal-Hall worked at Index at one of the most pivotal eras in recent world history. In 1993 the Twin Towers still stood, the world wide web was in its infancy and South African apartheid continued to be enforced. By 2007 the political and social landscape had become almost unrecognisable.

Under Vidal-Hall’s stewardship, Index navigated this global metamorphosis, identifying those in power who obscured the truth, those who were being shut out of the narrative, and gave the “voiceless a voice”.

How did Vidal-Hall find herself editing the magazine in 1993?

“It’s quite a long story, it’s a bit of a saga,” she told me over sausage rolls and tea. And a bit of a saga it really is. Returning to the UK in 1976 after a couple years of travelling, Vidal-Hall approached the Guardian, on behalf of a Bangladeshi friend, to start the Guardian Third World Review. It was, she said, “an absolutely pioneering supplement where third world people told their own stories”.

She remembers a Guardian journalist at the time asking her: “Don’t you think we treat the third world fairly?”. “That’s not the point.” she had replied. “You’re keeping their voices out…I didn’t use the word at the time I don’t think, but they’re censored. You keep them out.

Without skipping a beat, she added: “We then started a magazine called South.” South: The Voice of the Third World, was a monthly magazine which was about including other voices. South closed its doors in 1989 and, Vidal-Hall chuckled, “my husband buggered off at the same time so I was left with no husband, no income”.

Shortly after, she received a call from Philip Spender, who was running Index, asking for a reference for Andrew Graham-Yooll, who had been an editor at South. Graham-Yooll became the editor of Index, and it was he who brought Vidal-Hall into the fold.

It was not the best time for Index. Many of Index’s funders had seen it as “a Cold War weapon” and, believing communism to be over with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, they had withdrawn their funding. By the early 1990s Index was “basically bankrupt”.

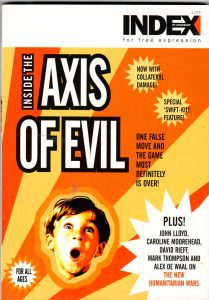

Inside the axis of evil, the spring 2003 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Enter the Fritt Ord Foundation, a group of Norwegian newspaper owners “ashamed of the takeover of their media by the Nazis in the [19]40s, and they had made a resolution, never again to work for anyone but themselves and to support independent media.”

And so in 1993, supported by funds from the Fritt Ord Foundation, Index was relaunched with Vidal-Hall as the editor, who had some big plans.

“One was to make it an attractive, readable magazine.”

Next: “I wanted it to be much more diverse…it did have a sort of Cold War focus and I wanted to bring in a much more global focus.”

“The third thing I wanted was to get rid of the idea that censorship was what they did out there, not what we did. They censor, we don’t. So I wanted to make it universal, the concept of censorship.”

I discuss with Vidall-Hall an Index article from 2002 by Noam Chomsky, Confronting the Monster. In this article Chomsky, writing in the wake of 9/11, examines how the West considers only actions taken by the enemy to be war crimes, while believing their own actions are always justified.

“He was so much my hero,” Vidal-Hall said on hearing Chomsky’s name.

“The them and us, it’s a good way to put it [referencing Chomsky’s article]. They do it, we don’t. And I wanted to break that, so that was my main [aim], to make Index inclusive not only of all genders, colours etc and creeds, don’t forget creeds, but also to make it inclusive of us, as guilty as them in a different way.”

Underexposed, the November 1999 edition of Index on Censorship magazine, which was Vidal-Hall’s favourite to work on

As we discuss Chomksy’s article, I ask what was the most important global event that happened while Vidal-Hall was at Index.

She says gathering around the television in the office to watch events on 9/11 unfolding live: “And that in some ways was the beginning of what I would call a series of events. It changed the balance, the perspective, relationships and priorities in the world. So, off the cuff, I would say that the sequence of events between 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq…that was the changing moment.”

The conversation turns to media coverage of that time. How were the narratives controlled by the states in question? What did it mean for freedom of expression?

“[In 2001-2003] people thought they had freedom of expression but they didn’t know the facts. And why didn’t we know the facts? We were lied to, there were no weapons of mass destruction.”

She added: “For me, and it’s very personal, what that invasion did was destroy a level of what seemed like stability in international relations. And I think the revelations of the inquiry into the lies that have been told was quite shocking… Are governments transparent? No! When they need to lie they will lie if it defends them.”

While the events of 2001 to 2003 were the most important during Vidal-Hall’s time as editor, her favourite issue predates them. It is a 1999 issue called Underexposed, which explored the censorship of photographs.

“It was fascinating. I didn’t go to the office for days. I spent weeks searching [for images]…some of the ones I remember most clearly, visually, are the ones from the early 30s when Hitler was coming to power. The photos that were never published. I’ll give you one example. Never published in Germany! Photos of him. There’s this one photo where he’s being coached in sort of rhetoric and he didn’t want people to know that he was being coached.”

Vidal-Hall also reflects on interviews she conducted in the early 1990s, one with a key player in modern European far-right politics.

“When the [Berlin] Wall came down I went out to Hungary and various other places…I did some rather interesting interviews…One of them was with a man you might have heard of, Viktor Orban. I interviewed him back when the Wall had come down, communism had fallen and him and another young man whom I’m still in touch with, Peter Molnar, I interviewed them together. They were the founder of Fidesz, the party that has now gone extreme right. And Orban seems to have undergone a personality change.”

Meditating on far right politics in Europe today, Vidal-Hall said: “How much of it is our mistake in thinking that democracy can just be delivered to the door by Amazon in a parcel with a smile?”

This gloomy take is offset by Vidal-Hall’s praise for Index: “As a publication you are unique, there is nobody else who is doing what index is doing. And that is extraordinary, to remain so. I feel strongly about that.”

The interview wraps up and I leave, my mind awash with the battles Index has won alongside all of those that we are still fighting today. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]